N8 Rathcormac/Fermoy Bypass Scheme Archaeological Services Contract Phase 2 – Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Vacancies 26Th May 2021 Title and Location

Job Vacancies 26th May 2021 Title and Vaccination Support Role - Fermoy, Co. Cork Location: McCauley Health and Beauty Pharmacy - Fermoy, County Cork Description: We are currently recruiting for Vaccination Support Role for a three month contract working full-time hours in our Fermoy, Co. Cork location. The Vaccination Support role will be based in one of our re-purposed Vaccination Centres supporting the delivery of the Covid-19 Vaccination Role out. The role would involve the gathering of information from suitable patients, the booking of appointments, contributing to an efficient workflow within the vaccination centre through effective communication with patients attending for vaccination and the input of patient/vaccinator details post vaccination. The Vaccination Support Role will be working with a team consisting of a lead vaccinator, pharmacist vaccinators and depending on the location in tandem with another Vaccination Support Role. Link: click here Title and Water Filtration Technician/ Plumber Location: CWS Water Solutions - County Cork Description: WS Water Solutions are recruiting an experienced Water Filtration Technician. The ideal candidate must: • Have at least 2 years plumbing experience. • Have working knowledge in the water filtration industry • Candidate must have a C licence with no more than 2 penalty points, for insurance purposes. • Have a willingness to learn. Key Duties/Responsibilities: • Cleaning and disinfection of cold water storage tanks. • Sanitisation of lines. Link: click here Title and Grounds Person Location: Trabolgan Holiday Village – County Cork Description: Duties • To have a knowledge and understanding of the way in which to care for, manage and develop identified garden areas, including soil cultivation, digging, forking, mulching, watering, raking, weeding, edging, maintaining lawns/grassy areas, seed sowing, bed preparation, planting, cutting and spraying (course required). -

Planning Applications

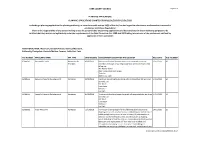

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 11/01/2020 TO 17/01/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION M.O. DATE M.O. NUMBER 19/00303 Deirdre McCarthy Permission for 08/05/2019 Permission for the following works to a protected structure: 14/01/2020 16 Retention retention of change of use of ground floor unit from retail use to office use The Round Tower Main Street & Barrack Street, Townlots Bantry, Co. Cork 19/00554 Connolly Property Developments Permission 23/08/2019 Construct a dwelling house along with all associated site works on 17/01/2020 20 serviced site Site No. 7 Cove View Baltimore Co. Cork 19/00555 Connolly Property Developments Permission 26/08/2019 To construct dwelling house along with all associated site works on 17/01/2020 21 serviced site Site No. 2 Cove View Baltimore Co. Cork 19/00662 Aiden McCarthy Permission 11/10/2019 Permission is being sought for the following works to existing 14/01/2020 13 dwelling house and attached ruinous outbuilding; (i) demolition of existing single storey annex to rear of house, (ii) construction of new two storey extension to rear, (iii) renovations to existing house including installation of 4 no. -

M8-Rathcormac-Fermoy-Bypass-Co

M8 RATHCORMAC/FERMOY BYPASS, M8 RATHCORMAC/FERMOY BYPASS, County Cork County Cork what we found background The M8 Rathcormac/Fermoy Bypass is 17.5 km long and extends from the northern end of the new in brief: N8 Glanmire-Watergrasshill Bypass, passing to the west Some of the findings from the scheme. of Rathcormac and to the east of Fermoy, tying into the existing N8 Cork-Dublin road at Moorepark. Extensive 1 archaeological investigations were carried out in pre- 1. Neolithic pottery construction, by Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd (ACS Ltd) on behalf of the National Roads Authority and Western Neolithic pottery uncovered Cork County Council. During construction, additional during excavations at Curraghprevin. investigations were carried out by Eachtra Archaeological Projects, on behalf of the construction company Direct (Photo ACS Ltd) Route (Fermoy) Ltd. A combined total of 50 sites were Ditch of the ringfort uncovered at Skahanagh North. (Photo ACS Ltd) archaeologically investigated. For more information 2 late glacial/early holcene please contact: 2. Corn-drying kiln Giant Irish Deer Archaeology Section Early medieval corn-drying kiln uncovered National Roads Authority At Ballyoran, in an area of fen bog nestled between the summits archaeological St. Martins House of Corrin and Ballyoran, the remains of six adult male Giant Irish at Scartbarry. (Photo ACS Ltd) Waterloo Road, Dublin 4 Deer (Megaloceros giganteus) were discovered.They were buried about 1.5 m into soft clay, underlying peat.The clay was formed by Tel: +353 1 660 2511 DISCOVERIES a lake that existed towards the end of the last ice age.The Giant Fax: +353 1 668 0009 Irish Deer remains were dated to 11139 – 10962 BC.These Email: [email protected] magnificent creatures (now extinct) would have been almost Web: www.nra.ie 3 3. -

Cloyne Diocesan Youth and Community Services (CDYS)

COVID-19 CYPSC Contingency Arrangements for the Coordination of Services Name of Agency: Service Delivery Area:1 Service Offer/Approach – online/face Contact details – phone, social to face/when media platform etc. Cloyne Diocesan Youth and Community Services (CDYS) Manager/Coordinator of Services: 1. Targeted Youth Work Projects Target supports to vulnerable young Youth Projects / Detached Youth - open to existing and people as identified by CDYS and CETB Projects – Miriam 086 8031206 Brian Williams – CEO vulnerable young people in Miriam Nyhan – Youth Work Manager Mallow, Fermoy, Mitchelstown and Midleton Victoria O’Brien – CCA and Family Support Karen O’Reilly – Finance and Admin Manager 2. Detached and Outreach Youth Detached youth workers engaging Youth Projects / Detached Youth Workers – Carrigtwohill and with isolated young people in both Projects – Miriam 086 8031206 Macroom Carrigtwohill and Macroom towns. 3. Garda Youth Diversion Youth Working with young people engaged Projects – Mallow, Cobh, with the justice system, referred by IYJS Projects Mobile to cover JLO’s. Referral based only – call Miriam Mitchelstown/Charleville/ 086 8031206 Midleton/Fermoy and All provide phone supports, digital environs groups, one to one’s, activities using digital platforms such as Zoom etc. 1 Please specify whether service is open to all or to an existing client group. Name of Agency: Service Delivery Area:1 Service Offer/Approach – online/face Contact details – phone, social to face/when media platform etc. Cloyne Diocesan Youth and Community Services (CDYS) 4. Community Based Drugs Referral based community supports Macroom Area – Kevin 0868031109 Workers (CBDO’s) for people or families struggling with alcohol or substance use/misuse. -

Cork East Notice of Situation

Box Polling Electoral Division: Townlands (Elector Numbers) Polling Station: Number District 133 CO15 - COBH URBAN (PART OF): BEAUSITE TERRACE, COBH TO BUNSCOIL RINN AN FO WHITEPOINT MOORINGS, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. 1 - 783) CHABHLAIGH 1 134 DO COBH URBAN (PART OF): GARDINERS WALK, RUSHBROOKE LINKS, COBH TO WOODSIDE, RUSHBROOKE MANOR, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. BUNSCOIL RINN AN 784 - 1425) CHABHLAIGH 2 135 DO COBH URBAN (PART OF): BROOKLAWN, COBH TO NORWOOD BUNSCOIL RINN AN PARK, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. 1426 - 2114) CHABHLAIGH 3 136 DO COBH URBAN (PART OF): ASSUMPTION PLACE, RINGMEEN, COBH BUNSCOIL RINN AN TO STACK TERRACE, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. 2115 - 2806) CHABHLAIGH 4 137 DO COBH URBAN (PART OF): ASHGROVE, CLUAIN ARD, COBH TO BUNSCOIL RINN AN WILLOW PARK, CLUAIN ARD, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. 2807 - 3330) CHABHLAIGH 5 138 DO COBH URBAN (PART OF): BROOKVALE, COBH TO SUMMERFIELDS, BUNSCOIL RINN AN RINGMEEN, COBH (ELECTOR NOS. 3331 - 3956) CHABHLAIGH 6 139 CO13 - CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): ANNGROVE, CARRIGTWOHILL TO CARRIGTWOHILL COMMUNITY FM WOODSTOCK, CARRIGTWOHILL (ELECTOR NOS. 1 - 789) HALL 1 140 DO CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): AHERN AND RYAN TERRACE, CARRIGTWOHILL TO WESTEND, CARRIGTWOHILL (ELECTOR NOS. CARRIGTWOHILL COMMUNITY 790 - 1548) HALL 2 141 DO CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): ALDER GROVE, FOTA ROCK, CARRIGTWOHILL TO THE WILLOWS, FOTA ROCK, CARRIGTWOHILL CARRIGTWOHILL COMMUNITY (ELECTOR NOS. 1549 - 2058) HALL 3 142 DO CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): CLONEEN, CARRIGTWOHILL TO CARRIGTWOHILL COMMUNITY WATER ROCK, MIDDLETON (ELECTOR NOS. 2059 - 2825) HALL 4 143 DO CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): AN CAIREAL, CUL ARD, ROCKLANDS, CARRIGTWOHILL TO FAOIN TUATH, CUL ARD, ROCKLANDS, CARRIGTWOHILL COMMUNITY CARRIGTWOHILL (ELECTOR NOS. 2826 - 3578) HALL 5 144 DO CARRIGTWOHILL (PART OF): ARDCARRIG, CASTLELAKE, CARRIGTWOHILL TO ROSSMORE, CARRIGTWOHILL (ELECTOR NOS. -

Strategic Development Opportunity

STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Fermoy Co. Cork FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY (AVAILABLE IN ONE OR MORE LOTS) DEVELOPMENT LAND FOR SALE SALE HIGHLIGHTS > Total site area extends to approximately 3.4 ha (8.4 acres). > Zoned Town Centre Mixed Use in the Fermoy Town Centre Development Plan. > Excellent location in the heart of Fermoy Town Centre. > Conveniently located approximately 35kms north east of Cork City Centre. > Location provides ease of access to the M8 and N72. > For sale in one or more lots. LOCATION MAP LOT 1 LOT 2 FERMOY, CO. CORK THE OPPORTUNITY DISTANCE FROM PROPERTY Selling agent Savills is delighted to offer for M8 3km sale this development opportunity situated in the heart of Fermoy town centre within N72 Adjacent walking distance of all local amenities. The Jack Lynch Tunnel & M8 29km property in its entirety extends to 3.4 ha (8.4 acres), is zoned for Town Centre development Cork City Centre 35km and is available in one or more lots. The site is Little Island 32km well located just off Main Street Fermoy with ease of access to the M8, the main Cork to Kent railway station 24km Dublin route. The opportunity now exists to Cork Airport 30km acquire a substantial development site, in one or more lots, with value-add potential in the Pairc Ui Chaoimh 25km heart of Fermoy town centre. Mallow 30km Doneraile Wildlife Park 29km LOCATION Mitchelstown 20km The subject property is located approximately 35km north east of Cork City Centre and approximately 30km east of Mallow and approximately 20km south of Mitchelstown. -

![Reverend Richard Townsend [612] St Cohnan's, Cloyne](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5851/reverend-richard-townsend-612-st-cohnans-cloyne-755851.webp)

Reverend Richard Townsend [612] St Cohnan's, Cloyne

Reverend Richard Townsend [612] Killenemer 1799 - 1801 Lackeen 1801 - 1806 Magourney 1801 - 1806 Ballyvourney 1799 - 1801 Cloyne St Cohnan’s, Cloyne Extract from Brady’s Clerical and Parochial Records of Cork, Cloyne and Ross Volume II 1863 Extracts from Samuel Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary 1837 BALLYVOURNEY, a parish, in the barony of WEST MUSKERRY, county of CORK, and province of MUNSTER, 8 miles (W. by N.) from Macroom; containing 3681 inhabitants. St. Abban, who lived to a very advanced age and died in 650, founded a nunnery at this place, which he gave to St. Gobnata, who was descended from O'Connor the Great, Monarch of Ireland. Smith, in his history of Cork, notices the church of this establishment, but it has since fallen into decay. The parish, of which the name signifies "the Town of the Beloved," is chiefly the property of Sir Nicholas C. Colthurst, Bart.; it is situated on the River Sullane, and on the road from Cork to Killarney, and comprises 26,525 statute acres, as applotted under the tithe act, and valued at £6073. 15. per annum. The surface is very uneven, in some parts rising into mountains of considerable elevation, the highest of which is Mullaghanish: about one- half is arable and pasture land, with 70 acres of woodland. Much of the land has been brought into a state of cultivation by means of a new line of road from Macroom, which passes through the vale of the Sullane, and is now a considerable thoroughfare; and great facilities of improvement have been afforded by other new lines of road which have been made through the parish; but there are still about 16,000 acres of rough pasture and moorland, which might be drained and brought into a state of profitable cultivation. -

The Irish Crokers Nick Reddan

© Nick Reddan Last updated 2 May 2021 The Irish CROKERs Nick Reddan 1 © Nick Reddan Last updated 2 May 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 Background ................................................................................................................................ 4 Origin and very early records ................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgments.................................................................................................................. 5 Note ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Origin ......................................................................................................................................... 6 The Settlers ................................................................................................................................ 9 The first wave ........................................................................................................................ 9 The main group .................................................................................................................... 10 Lisnabrin and Nadrid ............................................................................................................... 15 Dublin I ................................................................................................................................... -

N8 Rathcormac/Fermoy Bypass Scheme Archaeological Services Contract Phase 2 – Resolution

N8 Rathcormac/Fermoy Bypass Scheme Archaeological Services Contract Phase 2 – Resolution Final Report on Archaeological Excavation of Ballynahina 1 Townland: Ballynahina, Co. Cork Licence no.: 03E1186 Archaeological Director: Annette Quinn December 2005 Archaeological Consultancy Cork County Council Services Limited PROJECT DETAILS Project N8 Rathcormac- Fermoy Bypass Scheme Site Name Ballynahina I Licence No. 03E1186 Archaeologist Annette Quinn Townland Ballynahina Nat. Grid Ref. 180464, 093880 OS Map Ref. OS 6 inch sheet 44 Chainage 9550 Report Type Final Report Status Approved Date of Submission 19th December 2005 Distribution Ken Hanley Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd. Ballynahina I, N8 Rathcormac/Fermoy Bypass NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY The proposed N8 Rathcormac Fermoy By-Pass is approximately 17.5km in length and will extend from the northern end of the new N8 Glanmire-Watergrasshill Bypass in the townland of Meenane, passing to the west of Rathcormac and to the east of Fermoy and onto the northern tie- in point on the existing N8 Cork-Dublin Road at Moorepark West. A programme of advance archaeological investigation (phase one) was undertaken in May 2002, September 2002 and July 2003 under licences 02E0713-02E0720 issued by Duchas The Heritage Service to Donald Murphy and Deirdre Murphy. A total of forty-four sites were identified during this phase of works and they were subsequently resolved in 2003 during the second phase of the project (resolution phase). Ballynahina was initially identified during testing (phase 1) as a number of drains, a burnt mound/fulacht fiadh and a number of possible pits. Archaeological resolution of this site commenced on the 6th October 2003 and was carried out by Annette Quinn under licence number 03E1186. -

A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork

Munster Technological University SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit Masters Engineering 1-1-2019 A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork Liam Dromey Cork Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Structural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Dromey, Liam, "A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork" (2019). Masters [online]. Available at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering at SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Liam Dromey Supervisors: Kieran Ruane John Justin Murphy Brian O’Rourke __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Ageing highway structures present a challenge throughout the developed world. The introduction of bridge management systems (BMS) allows bridge owners to assess the condition of their bridge stock and formulate bridge rehabilitation strategies under the constraints of limited budgets and resources. This research presents a decision-support system for bridge owners in the selection of the best strategy for bridge rehabilitation on a highway network. The basis of the research is an available dataset of 1,367 bridge inspection records for County Cork that has been prepared to the Eirspan BMS inspection standard and which includes bridge structure condition ratings and rehabilitation costs. -

Church of Ireland Parish Registers

National Archives Church of Ireland Parish Registers SURROGATES This listing of Church of Ireland parochial records available in the National Archives is not a list of original parochial returns. Instead it is a list of transcripts, abstracts, and single returns. The Parish Searches consist of thirteen volumes of searches made in Church of Ireland parochial returns (generally baptisms, but sometimes also marriages). The searches were requested in order to ascertain whether the applicant to the Public Record Office of Ireland in the post-1908 period was entitled to an Old Age Pension based on evidence abstracted from the parochial returns then in existence in the Public Record Office of Ireland. Sometimes only one search – against a specific individual – has been recorded from a given parish. Multiple searches against various individuals in city parishes have been recorded in volume 13 and all thirteen volumes are now available for consultation on six microfilms, reference numbers: MFGS 55/1–5 and MFGS 56/1. Many of the surviving transcripts are for one individual only – for example, accessions 999/562 and 999/565 respectively, are certified copy entries in parish registers of baptisms ordered according to address, parish, diocese; or extracts from parish registers for baptismal searches. Many such extracts are for one individual in one parish only. Some of the extracts relate to a specific surname only – for example accession M 474 is a search against the surname ”Seymour” solely (with related names). Many of the transcripts relate to Church of Ireland parochial microfilms – a programme of microfilming which was carried out by the Public Record Office of Ireland in the 1950s. -

Parish Diocese Event Starts Ends Notes Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms

Parish Diocese Event Starts Ends Notes Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1877 Aghabullog Cloyne Burials 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Burials 1864 1879 Aghabullog Cloyne Marriages 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Marriages 1864 1882 Aghabullog Cloyne Notes surnames as Christian names Aghada Cloyne Baptisms 1838 1864 Aghada Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1902 Aghada Cloyne Burials 1838 1864 Aghada Cloyne Burials 1864 1914 Aghada Cloyne Combined 1729 1838 gaps 1737-60, 1770-75, 1807-1814 Aghada Cloyne Marriages 1839 1844 Aghada Cloyne Marriages 1845 1903 Aghern Cloyne Marriages 1846 1910 Aghern Cloyne Marriages 1911 1980 Aghada Cloyne MI Notes Ahinagh Cloyne MI Notes Ballyclough Cloyne Baptisms 1795 1864 Ballyclough Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1910 & 1911 to 1920 left unscanned Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1799 1830 extracts only Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1831 1864 Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1864 1920 Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1801 1840 extracts only Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1831 1844 Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1845 1900 Ballyclough Cloyne Recantation 1842 Ballyhea Cloyne Baptisms 1842 1864 Ballyhea Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1910 1911 to 1950 left unscanned Ballyhea Cloyne Burials 1842 1864 Ballyhea Cloyne Burials 1864 1920 gap 1903 & 1904 Ballyhea Cloyne Combined 1727 1842 Ballyhea Cloyne Marriages 1842 1844 Ballyhea Cloyne Marriages 1845 1922 gap 1900 to 1907 Ballyhooly Cloyne Baptisms 1789 1864 extracts only Ballyhooly Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1900 only partial Ballyhooly Cloyne Burials 1785 1864 extracts only Ballyhooly Cloyne