Can Post Bankruptcy Performance Be Predicted?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 42-0823980 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For The Fiscal Year Ended September 29, 2019 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 1-6227 LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its Charter) Delaware 42-0823980 (State of incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 4600 E 53rd Street, Davenport, Iowa 52807 (Address of principal executive offices) (563) 383-2100 Registrant's telephone number, including area code Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol(s) Name of Each Exchange On Which Registered Common Stock - $0.01 par value LEE New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes [ ] No [X] Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes [ ] No [X] Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes [X] No [ ] Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this Chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit). -

LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): October 17, 2005 _______________________________________________________________________ LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) _______________________________________________________________________ Commission File Number 1-6227 Delaware 42-0823980 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 201 N. Harrison Street, Davenport, Iowa 52801 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (563) 383-2100 Registrant’s telephone number, including area code _____________________________________________________________________________________ Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 5.02 Departure of Directors or Principal Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Principal Officers. Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (the "Company") has elected Linda Lindus as a Vice President-Publishing effective October 17, 2005. She will continue to be Publisher of The Pantagraph in Bloomington, IL and oversee publishing operations in Decatur, Mattoon and Charleston, IL. Ms. Lindus will gain responsibility for newspapers in Auburn, NY; Carlisle, PA; Orangeburg, SC; and Maysville, KY. -

LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): October 22, 2007 _______________________________________________________________________ LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) _______________________________________________________________________ Commission File Number 1-6227 Delaware 42-0823980 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 201 N. Harrison Street, Davenport, Iowa 52801 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (563) 383-2100 Registrant’s telephone number, including area code _____________________________________________________________________________________ Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 5.02 Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Principal Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers. On October 22, 2007, Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (the “Company”) issued a News Release announcing the retirement of John VanStrydonck, a Vice-President – Publishing of the Company, effective October 31, 2007. At or prior to his retirement Mr. VanStrydonck will resign from his positions as a Vice-President – Publishing of the Company, as an officer or director of certain subsidiaries of the Company and as Publisher of the Missoulian. -

Lee Enterprises Provides Update on Digital Transformation Strategy and Growth Targets

4600 E. 53rd Street Davenport, IA 52807 lee.net LEE ENTERPRISES PROVIDES UPDATE ON DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION STRATEGY AND GROWTH TARGETS Three-Pillar Strategy Focused on Growing Base of Annualized Recurring Revenue and Driving Shareholder Value Also Announces Stock Exchange Listing Transfer to Nasdaq Company to Host Conference Call at 9:00 a.m. CT Today DAVENPORT, Iowa – April 5, 2021 – Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (NYSE: LEE), a major subscription and advertising platform and a leading provider of high quality, trusted, local news and information in 77 markets, today provided an update on its digital transformation and growth strategy. “With strong momentum, including the completion of a compelling transaction with Berkshire Hathaway in fiscal 2020, Lee is accelerating our transformation as a top digital news and information provider,” said Kevin Mowbray, President and Chief Executive Officer. “Today, Lee is the fastest growing digital subscription platform in local media, and we are building on our bold course for our digital future as we enter our next chapter. We will be guided by a multi-year strategy that leverages our attractive market position, enhanced balance sheet, well-established digital infrastructure, and talented team. As we execute, Lee will expand our subscriber base, grow our base of annualized recurring revenue, drive new revenue streams with enhanced capabilities for advertisers, and create value for shareholders.” Mowbray continued, “We are focused on unlocking the full value of Lee, consistent with the valuations -

Form 8-K/A Lee Enterprises

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K/A CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): March 7, 2014 _______________________________________________________________________ LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) _______________________________________________________________________ Commission File Number 1-6227 Delaware 42-0823980 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 201 N. Harrison Street, Davenport, Iowa 52801 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (563) 383-2100 Registrant’s telephone number, including area code _____________________________________________________________________________________ Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: [ ] Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) [ ] Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) [ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) [ ] Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 7.01 Regulation FD Disclosure. On February 18, 2014, Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (the “Company”) filed a Form 8-K announcing that its presentation of business and financial information that may be given to prospective institutional investors (the “Institutional Investor Presentation”) from time to time regarding the refinancing of the Company’s 2012 First Lien Loan Agreement may be found on the Company’s website at www.lee.net/financial. -

LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): November 27, 2007 _______________________________________________________________________ LEE ENTERPRISES, INCORPORATED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) _______________________________________________________________________ Commission File Number 1-6227 Delaware 42-0823980 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 201 N. Harrison Street, Davenport, Iowa 52801 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (563) 383-2100 Registrant’s telephone number, including area code _____________________________________________________________________________________ Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 5.02 Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Principal Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers. On November 27, 2007, Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (the “Company”) issued a News Release announcing, in part, that Linda Lindus, a Vice-President – Publishing of the Company, is resigning from her position as a Vice-President – Publishing of the Company and as an officer or director of certain subsidiaries of the Company. -

July 2, 2021 United Way of the Midlands Welcomes New Board

For Immediate Release: July 2, 2021 United Way of the Midlands Welcomes New Board Members United Way of the Midlands (UWM) is proud to announce the addition of eight community leaders to its board: Julie Bechtel, Theola Cooper, Jessica Heidebrecht, Carol Henrichs, Derek Leathers, Paul Maass, Joseph Sullivan III and Randy Wood. With their diverse backgrounds and expertise, these individuals will help guide the work of UWM, ensuring it is investing dollars wisely in nonprofit programs that are addressing social and economic disparities and meeting community members’ essential needs. UWM also recognizes the contributions of its outgoing board members: Mickey Anderson, President and CEO of Baxter Auto Group; Joel Falk, Regional President at UWM Bank; Alison Ingunza, Landscape Architect at HDR and outgoing Emerging Leaders Steering Committee Chair and Pam Kale, former Vice President of Nursing at CHI Health. Bechtel became President and Publisher of The Omaha World-Herald in March of 2020 and also serves as a Regional Publisher for Lee Enterprises, overseeing Iowa and Eastern Nebraska. She began her career in 1987 at the Des Moines Register and joined Lee Enterprises in 1998 as circulation manager in Lincoln. She was promoted to operations manager there in 2000. In 2002, she became the publisher of The Bismarck Tribune in North Dakota and advanced to publisher of the Quad-City Times in Davenport, Iowa, in 2005. There she also served as a group leader for Lee newspapers in Muscatine, Iowa; Maysville, Kentucky, and Orangeburg, South Carolina. She was promoted to publisher and regional executive in Lincoln in 2011 and led the Lincoln Journal Star from 2011-14. -

Newspapers Advertising and Specialty Publications Online Services

NEWSPAPERS ADVERTISING AND SPECIALTY PUBLICATIONS ONLINE SERVICES Bettendorf News n Gateway Times n Quad-City Advertiser n Thrifty Nickel n www.qcthriftynickel.com n Thrifty Nickel Wheel Deals n Classic Images n www.classicimages.com n www.filmsofthegoldenage.com n Muscatine Journal n www.muscatinejournal.com n Southern Illinoisan www.southernillinoisan.com n Flipside n Southern Hometown Shopper n Welcome Home n Prairie Shopper n www.theprairieshopper.com n Decatur Wheels For You n The Extra n Herald & Review n www.herald-review.com n Quad-City Times n www.qctimes.com n The Post www.muscatinepost.com n Sunday Express n Films of the Golden Age n Globe Advertiser n Mason City Shopper n www.masoncityshopper.com n Britt Tribune News n Globe-Gazette n www.globegazette.com n Town & Country Advertiser n Forest City Summit n www.northiowanews.com Summit Advertiser n Winnebago/Hancock Shopper n www.winnebagoshopper.com n Mitchell County Press-News n www.mcpress.com n Town & Country Shopper n Billings Gazette n www.billingsgazette.com n Autofinder n www.billingsthriftynickel.com n Western Business Work For You, Montana n Yellowstone Shopper n Mini Nickel n www.mininickel.com n Western Montana Shopper n Thrifty Nickel n The Montana Standard n www.montanastandard.com n Independent Record n www.helenair.com n The Adit n www.adit.com n West Shore News Clark Fork Valley Press n Lake County Leader n The Advertiser n Bigfork Eagle n www.bigforkeagle.com n Hungry Horse News n www.hungryhorsenews.com n Missoulian n www.missoulian.com n Post Script n Ravalli -

Lee Enterprises Refinances Pulitzer Notes with Berkshire Hathaway

Lee Enterprises refinances Pulitzer Notes with Berkshire Hathaway April 30, 2013 DAVENPORT, Iowa (April 30, 2013) -- Lee Enterprises, Incorporated (NYSE: LEE), a major provider of local news, information and advertising in 50 markets, has reached agreement with Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (NYSE: BRK.A, BRK.B) to refinance $94 million of long-term debt known as the Pulitzer Notes. The refinancing reduces the interest to a fixed rate of 9.0% and extends the maturity from December 2015 to April 2017. The current interest rate of 11.3% had been scheduled to increase to 12.05% in January 2014 and 12.8% in January 2015. Pulitzer Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Lee, will be a co-borrower in the new facility with its subsidiary St. Louis Post-Dispatch LLC. Pulitzer Inc. was previously a guarantor of the Pulitzer Notes. "We very much welcome Berkshire Hathaway's continued investment in Lee, which is now represented in all elements of our capital structure," said Mary Junck, Lee chairman and chief executive officer. "We and Berkshire share a strong belief in the enduring value of our business and the opportunities for growth in local markets such as ours. This financing will reduce our interest costs and allow the company to repay debt at an even faster pace." Warren E. Buffett, chairman and chief executive officer of Berkshire Hathaway, said: "Lee fits our definition of locally focused newspapers serving indispensable information in markets with a deep sense of community. We view a larger stake in Lee as a good investment for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders." In addition to the Pulitzer Notes, the company's debt structure consists of 1st and 2nd Lien facilities, along with a $40 million undrawn revolver. -

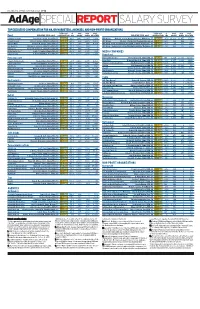

Ad Age Main 12-02-02 B 12 Aadb

December 2, 2002 | Advertising Age |S-12 AdAgeSPECIALREPORT SALARY SURVEY TOP EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION FOR MAJOR MARKETERS, AGENCIES, AND NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS TOTAL 2001 % 2001 2001 2001 TOTAL 2001 % 2001 2001 2001 Food EXECUTIVE, TITLE, & AGE COMPENSATION* CHG SALARY BONUS ALL OTHER EXECUTIVE, TITLE, & AGE COMPENSATION* CHG SALARY BONUS ALL OTHER Campbell Soup Co. Douglas R. Conant, Pres/CEO, 51 $3,237 86.6 $942 $1,987 $309 WPP Group Martin S. Sorrell, Group chief exec, WPP Group, 57 $3,623 35.9 $1,223 $1,875 $525 ConAgra Foods Bruce C. Rohde, Chmn/Pres/CEO, 53 5,970 508.2 950 2,969 2,051 WPP Group Michael J. Dolan, CEO Young & Rubicam, 55 1,632 696.1 800 800 32 General Mills Stephen W. Sanger, Chmn/CEO, 56 6,090 33.1 784 941 4,364 WPP Group Peter A. Schweitzer, Pres/CEO, J. Walter Thompson Co. 62 1,453 41.5 733 325 395 H.J. Heinz Co. William R. Johnson, Chmn/Pres/CEO, 53 5,199 13.1 1,050 368 0 WPP Group Shelly Lazarus, Chmn/CEO, Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide, 55 2,125 -79.2 850 775 500 Kellogg Co. Carlos M. Gutierrez, Chmn/Pres/CEO, 48 3,242 242.9 888 1,278 0 Philip Morris Cos.10 Louis C. Camilleri, Chmn/CEO, 47 3,132 -46.1 985 1,465 682 MEDIA COMPANIES Sara Lee Corp. C. Steven McMillan, Pres/CEO, 55 3,597 0.0 1,000 1,305 1,292 Broadcast Personal care General Electric Co.14 Jeffery R. Immelt, Chmn/CEO, 46 45,690 NA 3,325 10,000 32,365 71 9,206 21.5 4,357 3,000 1,849 Colgate-Palmolive Co. -

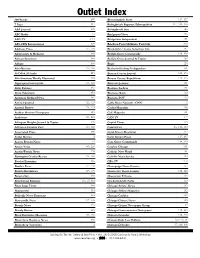

Outlet Index

Outlet Index 600 Words 207 Bloomingdale Press 117, 137 7 Days 217 Bolingbrook Reporter/Metropolitan 117, 140, 146 ABA Journal 185 Bolingbrook Sun 146 ABC Radio 31 Bridgeport News 226 ABC-TV 2, 16 Bridgeview Independent 151 ABS-CBN International 197 Brighton Park/McKinley Park Life 226 Addison Press 117, 136 Brookfield / Lyons Suburban Life 137 Adolescents & Medicine 185 Buffalo Grove Countryside 119, 128 African-Spectrum 189 Buffalo Grove Journal & Topics 128 Afrique 189 Bugle 126 Afro-Netizen 113, 189 Burbank-Stickney Independent 151 Al-Offok Al-Arabi 215 Bureau County Journal 121, 176 Alfa American Weekly Illustrated 203 Bureau County Republican 121, 176 Algonquin Countryside 118, 128 Business Journal 101 Alsip Express 151 Business Ledger 101 Alton Telegraph 153 Business Week 182 American Medical News 182 BusinessPOV 113 Antioch Journal 122, 123 Cable News Network - CNN 2 Antioch Review 118, 123 Cachet Magazine 190 Arabian Horizon Newspaper 215 Café Magazine 101 Arabstreet 113, 215 CAN TV 1, 7 Arlington Heights Journal & Topics 128 Capital Times 153 Arlington Heights Post 119, 128 Capitol Fax Sec 1:34, 109 Associated Press 108 Carol Stream Examiner 137 At the Movies 2 Carol Stream Press 117, 137 Aurora Beacon News 91 Cary-Grove Countryside 118, 129 Austin Voice 189, 224 Catalyst Chicago 101 Austin Weekly News 224 Catholic New World 101 Barrington Courier-Review 118, 128 Catholic News Service 109 Bartlett Examiner 136 CBS-TV 2, 8 Bartlett Press 117, 136 Champaign News Gazette 154 Batavia Republican 117, 136 Charleston Times-Courier 110, -

Northam Aims to Refill Coffers

SPORTS: VT basketball optimistic as practice begins. B1 A STRONG THUNDERSTORM 79 • 56 FORECAST, A2 | TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 | Waynesboro, Virginia | NewsVirginian.com ‘Patience is wearing thin’ towards unvaxxed vaccinated, and the data show people than just you.” “By choosing not to get vacci- Gov. Northam issues that vaccinations have few se- COVID case numbers in Vir- nated,you are absolutely hurting strong warning to the rious side effects, Northam said ginia have dropped in the past other people,” he said. “Unvac- at a Monday news conference. few days but are still way too cinated COVID patients are the unvaccinated Choosing not to get a vaccine high, Northam said. people filling up our hospitals could mean death, he reminded “Ask any exhausted nurse in right now, making it difficult for PATRICK WILSON the public. any hospital in Virginia,” he said. everyone else to get the hospital Richmond Times-Dispatch “If you know that and you still “Today we reported 1,997 new care that they need, and you are As frustration continues over don’t want the shot then I hope cases. That’s better than a cou- costing everyone a lot of money.” people who refuse to get the free you give some thought to how ple weeks ago, but it’s a whole lot Northam acknowledged there COVID-19 vaccine, Gov. Ralph your family will remember you,” more than the start of the sum- was probably little he could do Northam issued strong words he said. “Give some thought to mer when at one point we had to convince people who still ha- on Monday and suggested that what they’ll do without you.