Elvis Presley & the Beatles Author(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

CENTERS AROUND the WORLD Founder-Acarya: His Divine Grace A

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness CENTERS AROUND THE WORLD Founder-Acarya: His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Madurai, TN — 37 Maninagaram Main Road, 625 001/ Tel. (452) 274-6472 ASIA Mangalore, Karnataka — ISKCON Sri Jagannath Mandir, near Hotel Woodlands, Bunts Hostel Rd., INDIA 575 003/ Tel. (824) 2423326 or 2442756, or 9844325616 Agartala, Tripura — Radha Govinda Temple, Matchowmohani, 799 001/ Tel. (381) 2327053 ◆ Mayapur, WB — ISKCON, Shree Mayapur Chandrodaya Mandir, Mayapur Dham, Dist. Nadia, 741313/ or 9436167045/ [email protected] Tel. (3472) 245620, 245240 or 245355/ [email protected] Ahmedabad, Gujarat — Satellite Rd., Sarkhej Gandhinagar Highway, Bopal Crossing, 380 059/ Moirang, Manipur — Nongban Enkhol, Tidim Rd./ Tel. (3879) 795133 Tel. (79) 2686-1945, -1644, or -2350/ [email protected] ◆ Mumbai, Maharashtra — Hare Krishna Land, Juhu 400 049/ Tel. (22) 26206860/ [email protected]; (Guesthouse: [email protected]) [email protected] Allahabad, UP — Hare Krishna Dham, 161 Kashi Raj Nagar, Baluaghat 211 003/ ◆ Mumbai, Maharashtra — 7 K. M. Munshi Marg, Chowpatty 400 007/ Tel. (22) 23665500/ [email protected] Tel. (532) 2416718/ [email protected] Mumbai, Maharashtra — Bhaktivedanta Swami Marg, Hare Krishna Dham, Shristi, Sector 1, Near Royal College, Amravati, Maharashtra — Saraswati Colony, Rathi Nagar 444 603/ Tel. (721) 2666849 Mira Rd. (East), Thane 401 107/ Tel. (22) 28453562 or 9223183023/ [email protected] or 9421805105/ [email protected] Mysore, Karnataka — #31, 18th Cross, Jayanagar, 570 014/ Tel. (821) 2500582 or 6567333/ [email protected] Amritsar, Punjab — Chowk Moni Bazar, Laxmansar, 143 001/ Tel. (183) 2540177 Nagpur, Maharashtra — Bharatwada Road, Near Golmohar Nagar, Ramanuja Nagar, Kalamana Market, Aravade, Maharashtra — Hare Krishna Gram, Tal. -

Krishna-Avanti: History in the Making

June - July 2008 Dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Founder-Acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness Krishna-Avanti: History in the Making Srila Prabhupada: “Increasing one's love for God is a gradual process, and the first ingredient is faith. Without faith, there is no question of progress Hailing the Krishna-Avanti school as At the site, politicians, community a milestone in British history and an leaders and project donors joined in Krishna consciousness. That asset to Harrow, council leader David priests from Bhaktivedanta Manor. Led faith is created after reading Ashton participated in a landmark by His Holiness Atmanivedana Swami, Bhagavad-gita carefully and ceremony on Saturday 7th June. The the priests, assisted by community actually understanding it as it William Ellis playing fields, soon to be children, poured offerings of clarified home to the country’s first state-funded butter into a large sacred fire. is.... One must have faith in the Hindu school, hosted a traditional The Krishna-Avanti Primary School is words of Krishna, particularly ‘Bhumi Puja’ ceremony prior to the result of years of careful planning when Krishna says, ‘Abandon all commencement of building works. and discussion with the local authority dharmas and surrender to Me. I Christine Gilbert, Her Majesty's Chief and government. It will be UK’s first will give you all protection.’” Inspector of Ofsted was chief guest Hindu Voluntary Aided state school, at the Bhumi Puja. “I look forward and as such will not charge fees. It to the Krishna Avanti School being will open in September 2008 with a Teachings of Lord Kapila, 15.36, a centre of excellence and a very Reception class, and intake of pupils purport positive contribution to the Harrow will increase one year at a time. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment

Thursday 10 December 2015 Knightsbridge, London ENTERTAINMENT MEMORABILIA ENTERTAINMENT ENTERTAINMENT MEMORABILIA | Knightsbridge, London | Thursday 10 December 2015 22818 ENTERTAINMENT MEMORABILIA Thursday 10 December 2015 at 12noon Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES The following symbol is used Montpelier Street Natalie Downing to denote that VAT is due on Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 the hammer price and buyer’s London SW7 1HH [email protected] premium www.bonhams.com Consultant Specialist † VAT 20% on hammer price VIEWING Stephen Maycock and buyer’s premium Sunday 6 December +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 11am – 3pm [email protected] * VAT on imported items at Monday 7 December a preferential rate of 5% on 9am – 4.30pm Administrator hammer price and the prevailing Tuesday 8 December Sarah McLean rate on buyer’s premium 9am – 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 Wednesday 9 December [email protected] W These lots will be removed to 9am – 4.30pm Bonhams Park Royal Warehouse Thursday 10 December SALE NUMBER: after the sale. Please read the 9am – 10am 22818 sale information page for more details. BIDS CATALOGUE: +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 £15 Y These lots are subject to CITES +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax regulations, please read the To bid via the internet PRESS ENQUIRIES information in the back of the please visit www.bonhams.com [email protected] catalogue. TELEPHONE BIDDING CUSTOMER SERVICES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Bidding by telephone will only Monday to Friday The United States Government be accepted on lots with a lower 8.30am – 6pm has banned the import of ivory estimate of £500 or above. -

Visit a Krsna Temple Near

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness CENTERS AROUND THE WORLD Founder-Acarya: His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Patna, Bihar — Arya Kumar Rd., Rajendra Nagar, 800 016/ Tel. (0612) 687637 or 685081/ Fax: (0612) ASIA 687635/ E-mail: [email protected] INDIA Pune, Maharashtra — 4 Tarapoor Rd., Camp, 411 001/ Tel. (020) 633-2328 or 636-1855/ Agartala, Tripura — Assam-Agartala Rd., Banamalipur, 799 001/ Tel. (0381) 227053/ E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (0381) 224780/ E-mail: [email protected] Puri, Orissa — Bhakti Kuti, Swargadwar, 752 001/ Tel. (06752) 31440 Ahmedabad, Gujarat — Satellite Rd., Gandhinagar Highway Crossing, 380 054/ Puri, Orissa — ISKCON, Bhaktivedanta Ashram, Sipasirubuli, 752 001/ Tel. (06752) 30494 Tel. (079) 686-1945, 1645, or -2350/ E-mail: [email protected] Raipur, Chhattisgarh — Hare Krishna Land, opp. Mahrshi School, Alopi Nagar, Tatibandh/ Tel. (0771) Allahabad, UP — Hare Krishna Dham, 161 Kashi Raj Nagar, Baluaghat 211 003/ 637555/ E-mail: [email protected] Tel. (0532) 405294 Secunderabad, AP — 27 St. John’s Rd., 500 026/ Tel. (040) 780-5232/ Fax: (040) 814021 Bangalore, Karnataka — Hare Krishna Hill, 1 ‘R’ Block, Chord Rd., Rajaji Nagar 560 010/ Silchar, Assam — Ambikapatti, Silchar, Dist. Cachar, 788 004/ Tel. (03842) 34615 Tel. (080) 332-1956/ Fax: (080) 332-4818/ E-mail: [email protected] Siliguri, WB — ISKCON Road, Gitalpara, 734 406/ Tel. (0353) 426619 or 539046 or 539082/ Bangalore, Karnataka — ISKCON Sri Jagannath Mandir, No.5 Sripuram, 1st cross, Fax: (0353) 526130 Sheshadripuram, Bangalore 560 020/ Tel. (080) 353-6867 or 226-2024 or 353-0102 Sri Rangam, TN — 93 Anna Mandapam Rd., A-1 Caitanya Apartments, 620 006/ Tel. -

Vrindaban Days

Vrindaban Days Memories of an Indian Holy Town By Hayagriva Swami Table of Contents: Acknowledgements! 4 CHAPTER 1. Indraprastha! 5 CHAPTER 2. Road to Mathura! 10 CHAPTER 3. A Brief History! 16 CHAPTER 4. Road to Vrindaban! 22 CHAPTER 5. Srila Prabhupada at Radha Damodar! 27 CHAPTER 6. Darshan! 38 CHAPTER 7. On the Rooftop! 42 CHAPTER 8. Vrindaban Morn! 46 CHAPTER 9. Madana Mohana and Govindaji! 53 CHAPTER 10. Radha Damodar Pastimes! 62 CHAPTER 11. Raman Reti! 71 CHAPTER 12. The Kesi Ghat Palace! 78 CHAPTER 13. The Rasa-Lila Grounds! 84 CHAPTER 14. The Dance! 90 CHAPTER 15. The Parikrama! 95 CHAPTER 16. Touring Vrindaban’s Temples! 102 CHAPTER 17. A Pilgrimage of Braja Mandala! 111 CHAPTER 18. Radha Kund! 125 CHAPTER 19. Mathura Pilgrimage! 131 CHAPTER 20. Govardhan Puja! 140 CHAPTER 21. The Silver Swing! 146 CHAPTER 22. The Siege! 153 CHAPTER 23. Reconciliation! 157 CHAPTER 24. Last Days! 164 CHAPTER 25. Departure! 169 More Free Downloads at: www.krishnapath.org This transcendental land of Vrindaban is populated by goddesses of fortune, who manifest as milkmaids and love Krishna above everything. The trees here fulfill all desires, and the waters of immortality flow through land made of philosopher’s stone. Here, all speech is song, all walking is dancing and the flute is the Lord’s constant companion. Cows flood the land with abundant milk, and everything is self-luminous, like the sun. Since every moment in Vrindaban is spent in loving service to Krishna, there is no past, present, or future. —Brahma Samhita Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. -

"Chant and Be Happy": Music, Beauty, and Celebration in a Utah Hare Krishna Community Sara Black

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 "Chant and Be Happy": Music, Beauty, and Celebration in a Utah Hare Krishna Community Sara Black Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “CHANT AND BE HAPPY”: MUSIC, BEAUTY, AND CELEBRATION IN A UTAH HARE KRISHNA COMMUNITY By SARA BLACK A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Sara Black defended on October 31, 2008. __________________________ Benjamin Koen Professor Directing Thesis __________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member __________________________ Michael Uzendoski Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________________________________ Seth Beckman, Dean, College of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv List of Photographs v Abstract vi INTRODUCTION: ENCOUNTERING KRISHNA 1 1. FAITH, AESTHETICS, AND CULTURE OF KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS 15 2. EXPERIENCE AND MEANING 33 3. OF KRISHNAS AND CHRISTIANS: SHARING CHANT 67 APPENDIX A: IRB APPROVAL 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY 93 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 99 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Cymbal rhythm 41 Figure 2. “Mekala” beat and “Prabhupada” beat 42 Figure 3. Melodies for Maha Mantra 43-44 Figure 4. “Jaya Radha Madhava” 45 Figure 5. “Nama Om Vishnu Padaya” 47 Figure 6. “Jaya Radha Madhava” opening line 53 Figure 7. “Jaya Radha Madhava” with rhythmic pattern 53 Figure 8. “Jaya Radha Madhava” opening section 54 Figure 9. -

US Apple LP Releases

Apple by the Numbers U.S. album releases From the collection of Andre Gardner of NY, NY SWBO‐101 The Beatles The Beatles Released: 22 Nov. 1968 (nicknamed "The White Album") In stark contrast to the cover to Sgt. Pepper's LHCB, the cover to this two record set was plain white, with writing only on the spine and in the upper right hand corner of the back cover (indicating that the album was in stereo). This was the first Beatles US album release which was not available in mono. The mono mix, available in the UK, Australia, and several other countries, sounds quite different from the stereo mix. The album title was embossed on the front cover. Inserts included a poster and four glossy pictures (one of each Beatle). The pictures were smaller in size than those issued with the UK album. A tissue paper separator was placed between the pictures and the record. Finally, as in every EMI country, the albums were numbered. In the USA, approximately 3,200,000 copies of the album were numbered. These albums were numbered at the different Capitol factories, and there are differences in the precise nature of the stamping used on the covers. Allegedly, twelve copies with east‐coast covers were made that number "A 0000001". SI = 2 ST 3350 Wonderwall Music George Harrison Released: 03 Dec. 1968 issued with an insert bearing a large Apple on one side. Normal Copy: SI = 2 "Left opening" US copy or copy with Capitol logo: SI = 7 T‐5001 Two Virgins John Lennon & Yoko Ono Released: January, 1969 (a.k.a. -

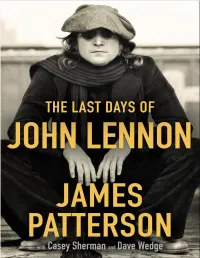

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Mexico 45 Others

APPLE 6391 - THINGUMYBOB / YELLOW SUBMARINE (John Foster & Sons Ltd. Black Dyke Mills Band) APPLE 6392 - THOSE WERE THE DAYS / TURN TURN TURN (Mary Hopkin) (X46416) and (5:06) not aligned 6392 print near middle (X46416) and (5:06) aligned, 6392 print on 1/3 from top of (X46416) and (5:06) not aligned 6392 print on 1/3 from top of 6392 starts under spacing label label between O & P in Hopkin (X46416) and (5:06) not 6392 print near middle aligned, 6392 starts under spacing between H & O in Hopkin APPLE 6393 - SOUR MILK SEA / THE EAGLE LAUGHS AT YOU (Jackie Lomax) APPLE 6411 - QUE TIEMPO TAN FELIZ / TURN TURN TURN (Mary Hopkin) APPLE 6446 - MAYBE TOMORROW / AND HER DADDY'S A MILLIONAIRE (The Iveys) APPLE 6467 - GOODBYE / SPARROW (Mary Hopkin) APPLE 6535 - THAT'S THE WAY GOD PLANNED IT / WHAT ABOUT YOU (Billy Preston) Promo Sliced Apple on A-side APPLE 6549 - SUNSET / IS THIS WHAT YOU WANT (Jackie Lomax) Promo APPLE 6564 - HARE KRISHNA MANTRA / PRAYER TO THE SPIRITUAL MASTERS (Radha Krishna Temple - London) Promo Small space over RADHA Large space over RADHA APPLE 6585 - GOLDEN SLUMBERS - CARRY THAT WEIGHT / TRASH CAN (Trash) APPLE 6617 - COME AND GET IT / ROCK OF ALL AGES (Badfinger) V in Ven starts under C in Come V in Ven starts under O in Come APPLE 6634 - TEMMA HARBOUR / LONTANO DAGLI OCCHI (Mary Hopkin) Promo APPLE 6673 - GOVINDA / GOVINDA JAI JAI (Radha Krishna Temple - London) Promo stamp APPLE 6727 - QUE SERA, SERA / FIELDS OF ST. ETIENNE (Mary Hopkin) Promo stamp, a.m.p.i.ascap. -

Pdf/Beatles Chronology Timeline

INDEX 1-CHRONOLOGY TIMELINE - 1926 to 2016. 2-THE BEATLES DISCOGRAPHY. P-66 3-SINGLES. P-68 4-MUSIC VIDEOS & FILMS P-71 5-ALBUMS, (Only Their First Release Dates). P-72 6-ALL BEATLES SONGS, (in Alphabetical Order). P-84 7-REFERENCES and Conclusion. P-98 1 ==================================== 1-CHRONOLOGY TIMELINE OF, Events, Shows, Concerts, Albums & Songs Recorded and Release dates. ==================================== 1926-01-03- George Martin Producer of the Beatles was Born. George Martin died in his sleep on the night of 8 March 2016 at his home inWiltshire, England, at the age of 90. ==================================================================== 1934-09-19- Brian Epstein, The Beatles' manager, was born on Rodney Street, in Liverpool. Epstein died of an overdose of Carbitral, a form of barbiturate or sleeping pill, in his locked bedroom, on 27 August 1967. ==================================================================== 1940-07-07- Richard Starkey was born in family home, 9 Madyrn Street, Dingle, in Liverpool, known as Ringo Starr Drummer of the Beatles. Maried his first wife Maureen Cox in 1965 Starr proposed marriage at the Ad-Lib Club in London, on 20 January 1965. They married at the Caxton Hall Register Office, London, in 1965, and divorced in 1975. Starr met actress Barbara Bach, they were married on 27 April 1981. 1940-10-09- JohnWinston Lennon was born to Julia and Fred Lennon at Oxford Maternity Hospital in Liverpool., known as John Lennon of the Beatles. Lennon and Cynthia Powell (1939– 2015) met in 1957 as fellow students at the Liverpool College of Art. The couple were married on 23 August 1962. Their divorce was settled out of court in November 1968.