Lowton, Zubeida (2021) Socio-Spatial Transformations: Johannesburg and Cape Town Public Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YES BANK LTD.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN Ground floor & First Arpan AND floor, Survey No Basak - NICOBAR 104/1/2, Junglighat, 098301299 ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Port Blair - 744103. PORT BLAIR YESB0000448 04 Ground Floor, 13-3- Ravindra 92/A1 Tilak Road Maley- ANDHRA Tirupati, Andhra 918374297 PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI, AP Pradesh 517501 TIRUPATI YESB0000485 779 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T. S. No. 2/5, Door no. 5-87-32, Lakshmipuram Main Road, Guntur, Andhra ANDHRA Pradesh. PIN – 996691199 PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur 522007 GUNTUR YESB0000587 9 Ravindra 1ST FLOOR, 5 4 736, Kumar NAMPALLY STATION Makey- ANDHRA ROAD,ABIDS, HYDERABA 837429777 PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD, D YESB0000424 9 MR. PLOT NO.18 SRI SHANKER KRUPA MARKET CHANDRA AGRASEN COOP MALAKPET REDDY - ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 64596229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD MALAKPET 500036 D YESB0ACUB02 4550347 21-1-761,PATEL MRS. AGRASEN COOP MARKET RENU ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA KEDIA - PRADESH HYDERABAD RIKABGUNJ 500002 D YESB0ACUB03 24563981 2-4-78/1/A GROUND FLOOR ARORA MR. AGRASEN COOP TOWERS M G ROAD GOPAL ANDHRA URBAN BANK SECUNDERABAD - HYDERABA BIRLA - PRADESH HYDERABAD SECUNDRABAD 500003 D YESB0ACUB04 64547070 MR. 15-2-391/392/1 ANAND AGRASEN COOP SIDDIAMBER AGARWAL - ANDHRA URBAN BANK BAZAR,HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 24736229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD SIDDIAMBER 500012 D YESB0ACUB01 4650290 AP RAJA MAHESHWARI 7 1 70 DHARAM ANDHRA BANK KARAN ROAD HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 D YESB0APRAJ1 23742944 500144259 LADIES WELFARE AP RAJA CENTRE,BHEL ANDHRA MAHESHWARI TOWNSHIP,RC HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD BANK BHEL PURAM 502032 D YESB0APRAJ2 23026980 SHOP NO:G-1, DEV DHANUKA PRESTIGE, ROAD NO 12, BANJARA HILLS HYDERABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABA PRADESH HYDERABAD BANJARA HILLS 500034 D YESB0000250 H NO. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Caprihans India Limited Kycdata List

Sr No of BANK MOBILE No FOLIONO NAME JOINTHOLDER1 JOINTHOLDER2 JOINTHOLDER3 ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 CITY PINCODE Shares SIGNATURE PAN1 DETAILS NO EMAIL NOMINATION DIPTIKA SURESHCHANDRA RAGINI C/O SHIRISH I NEAR RAMJI 1 'D00824 BHATT SURESHCHANDRA TRIVEDI PANCH HATADIA MANDIR,BALASINOR 0 0 35 REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED CHHOTABHAI BIDI JETHABHAI PATEL MANUFACTURES,M.G.RO 2 'D01065 DAKSHA D.PATEL & CO. AD POST SAUGOR CITY 0 0 40 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED DEVIPRASAD DAHYABHAI BATUK DEVIPRASAD 1597 3 'D01137 SHUKLA SHUKLA SHRIRAMJINISHERI KHADIA AHMEDABAD 1 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ANGODD MAPUSA 4 'E00112 EMIDIO DE SOUZA VINCENT D SOUZA MAPUSA CABIN BARDEZ GOA 0 0 70 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 5 'R02772 RAMESH DEVIDAS POTDAR JAYSHREE RAMESH POTDAR GARDEN RAJA PETH AMRAVATI P O 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED SHASTRI GANESH BLOCK NO A‐ AMARKALAPATARU CO‐ NAGAR,DOMBIVALI 6 'A02130 ASHOK GANESH JOSHI VISHWANATH JOSHI 6/2ND FLOOR OP HSG SOCIETY WEST, 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI CHIMANLAL NEAR MADHU PURA, 7 'A02201 PATEL DUDHILI NI DESH VALGE PARAMA UNJHA N.G. 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI BHAILALBHAI A‐3 /104 ANMOL OPP NARANPURA NARANPURA 8 'A03187 PATEL TOWER TELEPHONE EXCHANGE SHANTINAGAR AHMEDABAD 0 0 140 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED MIG TENAMENT PREMLATA SURESHCHANDRA NO 8 GUJARAT GANDHINAGAR 9 'P01152 PATEL HSG BOARD SECT 27 GUJARAT 0 0 77 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED C/O M M SHAH, 10 'P01271 PIYUSHKUMAR SHAH MANUBHAI SHAH BLOCK NO 1, SEROGRAM SOCIETY, NIZAMPURA, BARODA 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 169 THAPAR 11 'P02035 PREM NATH JAIN NAGAR MEERUT 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 92/6 MITRA PARA DT. -

South Africa Tour 2013

PEACE TRUTH AHIMSA SOUTH AFRICA TOUR 2013 TOUR 12 days tour of South Africa - tracing the journey that transformed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the lawyer into Mahatma Gandhi - the greatest peace leader of our times. The tour begins at the historic Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad and proceeds to Durban in South Africa. In Durban, explore the Phoenix Settlement, International Printing Press, Mahatma Gandhi Museum & Library and Durban Waterfront. A visit to the city of Pietermaritzburg and an opportunity to reenact the event at the Railway Station that sparked the philosophy of SATYAGRAHA and changed mankind. The tour involves 6 historic locations, 5 museums, 3 interactive workshops and meetings with historians, An overnight journey by railroad to Johannesburg. educationists and personalities that have dedicated Visit Johannesburg Law court -now Gandhi Square, their lives in the name of Gandhi in South Africa. Gandhi’s Law Offices/Court Chambers and Gaiety Theatre. An interactive session at the Satyagraha Gandhi Development Trust, Durban University of House, Gandhiji’s home from 1908-1910, now Technology, Hector Pieterson and the Apartheid a French boutique guest house and museum. Museum, the Harley owners group of Durban, the eThekwini Municipality and CIDA would actively Accompanying this tour will be the Ahimsa Harley - participate to make this a memorable experience. A Harley Davidson motorbike signed by 900 students from all over the world, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi. The tour will also juxtapose the journey of Nelson This bike will be escorted by biker groups from Mandela and Albert Lutuli, along with Mahatma Durban to Pietermaritzburg station via schools and Gandhi. -

Ahb2017 18112016

iz'kklfud iqfLrdk Administrative Hand Book 2017 Data has been compiled based on the information received from various offices. For any corrections/suggestions kindly intimate at the following address: DIRECTORATE OF INCOME TAX (PR,PP&OL) 6th Floor, Mayur Bhawan, Connaught Circus, New Delhi - 110001 Ph: 011-23413403, 23411267 E-mail : [email protected] Follow us on Twitter @IncomeTaxIndia fo"k; lwph General i`"B la[;k Calendars 5 List of Holidays 7 Personal Information 9 The Organisation Ministry of Finance 11 Central Board of Direct Taxes 15 Pr.CCsIT/Pr.DsGIT and Other CCsIT/DsGIT of the respective regions (India Map) 26 Key to the map showing Pr.CCsIT/Pr.DsGIT and Other CCsIT/DsGIT of the respective regions 27 Directorates General of Income-Tax DsGIT at a glance 28 Administration 29 Systems 32 Logistics 35 Human Resource Development (HRD) 36 Legal & Research 38 Vigilance 39 Risk Assessment 42 Intelligence & Criminal Investigation 42 Training Institutes Directorate General of Training (NADT) 47 Regional Training Institutes 49 Directorate General of Income Tax (Inv.) 53 Field Stations Pr. CCsIT at a glance 77 A - B 79-92 C 93-99 D - I 100-119 J - K 120-135 L - M 135-151 N - P 152-159 R - T 160-167 U - V 167-170 3 Alphabetical List of Pr. CCsIT/Pr. DsGIT & CCsIT/DsGIT 171 Rajbhasha Prabhag 173 Valuation Wing 179 Station Directory 187 List of Guest Houses 205 Other Organisations Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) 217 ITAT 217 Settlement Commission 229 Authority for Advance Rulings 233 Appellate Tribunal for Forfeited Property -

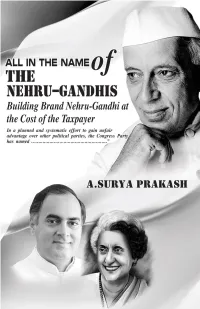

Nehru Gandhi Family Viz

ALL IN THE NAME OF THE NEHRU – GANDHIS Building Brand Nehru-Gandhi at the Cost of the Taxpayer A. SURYA PRAKASH 1 No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by : A.Surya Prakash 170, National Media Campus Gurgaon – 122002 For More See : asuryaprakash.com Author : A.Surya Prakash Edition First, 2014 2 The following is the list of Government Schemes and Projects; Universities and Educational Institutions; Ports and Airports; National Parks and Sanctuaries; Sports Tournaments, Trophies and Stadia; Hospitals and Medical Institutions; National Scientific and Research Institutions; University Chairs, Scholarships and Fellowships; Festivals; Power Projects; Peak and key Geographical Markers; and Roads and Buildings named after three members of the Nehru Gandhi family viz. Rajiv Gandhi, Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. This list includes most of the projects, schemes and institutions funded by the Union Government and the governments in the States. For details log on to asuryaprakash.com Government Schemes/ Projects Central Government Schemes 1. Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana, Ministry of Power - A scheme “Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana” for Rural Electricity Infrastructure and HouseHold Electrification was lauanched for the attainment of the National Common Minimum Programme of providing access to electrocity to all Rural Household by 2009. Rural Electificaiton Corporation (REC) is the nodal agency for the scheme. Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana to be continued during the Eleventh Plan period with a capital subsidy of Rs. -

Satyagraha Legacy to May Led by Satyagraha Legacy Tour of South Africa May 31 – June 14, 2014 Led by Dr. Arun Gandhi

Satyagraha Legacy Tour of South Africa May 31 – June 14, 2014 Gandhiji, as a satyagrahi, in South Africa http://www.gandhiforchildren.org/gandhi -india-tours/category/itinerary/legacytoursa/ Led by Dr. Arun Gandhi www.arungandhi.net 1 Day 1: May 31 2014 Fly into Durban International Airport Arrive in Durban International Airport, South Africa and transfer to the Protea Hotel Umhlanga to rest after the journey and have dinner followed by a presentation by tour leader Arun Gandhi and an introduction by guide on what to expect from the next few days. This opening occasion will be celebrated with a traditional Durban meal in a private venue. Mahatma Gandhi (Bapu) first arrived in South Africa in May 23, 1893. Mahatma Gandhi (Bapu) spent 21 years in South Africa . Gandhi’s concept and technique of non-violence ( Satyagraha ) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satyagraha originated in South Africa. The account of Bapu’s twenty-one years in which his influence was fundamental to the development of the whole freedom struggle. To know that history is to understand the history of the present moment. To understand its significance for peace, not only in South Africa, but in the world, is an essential duty for all who care about the future of our planet earth. Bapu stated he was born in India but was made in South Africa. Nelson Mandel a said, "South Africa received him as MK Gandhi and returned him to India as Mahatma Gandhi." Accommodations: Protea Hotel Umhlanga Meals : Dinner At 7:30 PM the group will meet Dr. Arun Gandhi Satyagraha Legacy Tour 2014 CostUS$4520.00 per person sharing a room Tour itinerary does not include airfare Sign-up Deadline 2/28/2014 2 Day 2: June 1 : South African Historical Overview Today we explore some of the broader aspects of South African history because it is important to put the country into perspective with regards to the challenges faced today as we continue to reconcile our past struggle with the current one. -

Black Lives Matter Saturday, October 17, 2020

Suggested Donation $6.00 Living Gandhi award Today Guest Editor: Dr. Paul Dekar Editor: Dr. Khursheed Ahmed GANDHI 150 The 28th Annual Phote: Courtesy of Bob Litch GANDHI PEACE FESTIVAL Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Towards a culture of peace, nonviolence and justice 2020 Theme: Black Lives Matter Saturday, October 17, 2020 Sponsored by India-Canada Society, Hamilton City of Hamilton McMaster University Faculty of Humanities www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/gandhi The 28th Annual Gandhi Peace Festival, October 2020 GANDHI 150 Words of Welcome ................................................................................................................................ 3 Our Sincere Thanks .............................................................................................................................. 4 Message from the President and Vice-Chancellor ................................................................................ 5 Greetings from the Centre for Peace Studies ....................................................................................... 6 Our Guest Editor ................................................................................................................................... 7 The City of Hamilton Senior of the Year Award Dr. Sri Gopal Mohanty ............................................... 8 Dr. Gary Warner to be honoured by McMaster University .................................................................... 9 An unusual Gandhi Peace Festival .................................................................................................... -

'Mahatma Gandhi's Importance Timeless'

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. November 1, 2012 I India RevieI w Vol. 8 Issue 11 www.indianembassy.org ‘Mahatma Gandhi’s importance timeless’ n India, US to deepen n Ambassador Rao n ‘King of Romance’ Yash economic cooperation inaugurates CGI Atlanta Chopra passes away Ambassador’s PAGE Global Leadership in 2020 I was invited to participate at a panel discussion at the Global Leadership Summit organized by the Meridian International Center on October 12, 2012 in Washington DC. I spoke at the Ambassador’s panel on ‘What a Good Global Leader (and Citizen) Looks Like in 2020’. eadership involves certain constants regardless of the era or time zone in which we L are placed. Human beings are not very different from each other regardless of the languages they speak or the cultures they belong to. Of course, the scale and extent of the challenges that humankind faces today is of a different order from even fifty years ago. When I was growing up in Bangalore, we would never have imagined the evil of suicide terrorism, or the rise of Al Qaeda. Today we have leaders and leaders. Leaders who advocate hate and violence have a larg - er following across the planet than ever before. Good leadership and good leaders have to develop effective Ambassador Nirupama Rao speaking at the first Meridian Global Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C. on October 12. Also seen is Ambassador Stuart Holliday, President and CEO of Meridian strategies to overcome and vanquish International Center. this opposition, and the fear, ignorance and the alienation that fuels the people’s agenda in all our democ - violence and terror. -

SR No HOSPITAL NAME

HOSPITAL NAME (Hospitals marked with** S R are Preffered Provider STD Telephon Address City Pin Rohini Code State Zone No Network, with whom ITGI code e has Negotiated package rates) 1 Aasha Hospital** 7-201, Court Road Anantapur 515001 08554 245755 8900080169586 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 2 Aayushman The Family Hospital**45/142A1, V.R. ColonyKurnool 518003 08518 254004 8900080172005 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 3 Akira Eye Hospital** Aryapuram Rajahmundry 533104 0883 2471147 8900080180079 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 4 Andhra Hospitals** C.V.R. Complex, PrakasamVijayawada Road 520002 0866 2574757 8900080172531 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 5 Apex Hospital # 75-6-23, PrakashnagarRajahmundry Rajahmundry 533103 0883 2439191 8900080334724 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 6 Apollo Bgs Hospitals** Adichunchanagari RoadMysore Kuvempunagar 570023 0821 2566666 8900080330627 Karnataka South Zone 7 Apollo Hospital 13-1-3, Suryaraopeta, MainKakinada Road 533001 0884 2379141 8900080341647 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 8 Apollo Hospitals,Vizag Waltair, Main Road Visakhapatnam 530002 0891 2727272 8900080177710 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 9 Apoorva Hospital 50-17-62 Rajendranagar,Visakhapatnam Near Seethammapeta530016 Jn. 0891 2701258 8900080178007 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 10 Aravindam Orthopaedic Physiotherapy6-18-3, KokkondavariCentre Street,Rajahmundry T. Nagar, Rajahmundry533101 East0883 Godavari2425646 8900080179547 Andhra Pradesh South Zone 11 Asram Hospital (Alluri Sitarama N.H.-5,Raju Academy Malaka OfPuram MedicalEluru Sciences)** 534005 08812 249361-62 8900080180895