Mother Feminism: a Study in Jewish American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Textual Analysis of Contemporary Mother Identities in Popular Discourse Katherine Mayer Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Mother: A Textual Analysis of Contemporary Mother Identities in Popular Discourse Katherine Mayer Marquette University Recommended Citation Mayer, Katherine, "Mother: A Textual Analysis of Contemporary Mother Identities in Popular Discourse" (2012). Master's Theses (2009 -). 142. https://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/142 MOTHER: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPOARY MOTHERING IDENTITIES IN POPULAR DISCOURSE by Katherine Marie Mayer, B.A. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2012 ABSTRACT MOTHER: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPOARY MOTHERING IDENTITIES IN POPULAR DISCOURSE Katherine Marie Mayer, B.A. Marquette University, 2012 For centuries, women have struggled to understand the meaning of one of their most important roles in society, mother. Internet discussion boards have become an important venue for women to participate in ongoing discussions about the role of mothering in contemporary society and serve as a means by which they are actively shaping society’s understanding of the role of mothers. A textual analysis of a popular mothering discussion board yielded two dominate mothering identities, tensions that exist for each mothering type and how mothers resolve those tensions through the mothering discourse. The study ultimately revealed the ways in which the mothering discourse serves as an important part of the identity construction process and is used as a means of negotiating, managing and ultimately reinforcing a mother’s own identity. i TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 Contemporary Conceptions of Mothers in Society 2 Rationale for Study 3 Preview of Thesis 4 II. -

The Role of Fathers in Parenting for Gender Equality

The role of fathers in Parenting for programs interacting with families actively promote gender equality and challenge restrictive norms, so that gender equality relationships, roles, institutional practices and services Clara Alemann1, Aapta Garg2, & Kristina Vlahovicova3 - can gradually evolve to create peaceful, non-violent and Promundo-US equitable societies and contribute to achieve SDG 16. Father–child relationships “be they positive, Men’s positive engagement as fathers goes well beyond negative or lacking, at any stage in the life of them stepping in to perform childcare and domestic the child, and in all cultural and ethnic tasks. This paper understands the concept of male communities – have profound and wide-ranging engagement as fathers to encompass their active impacts on children that last a lifetime”. participation in protecting and promoting the health, (Fatherhood Institute and MenCare) wellbeing and development of their partners and children. It also involves them being emotionally connected with their children and partners (even when 1. Introduction they may not be living together),–including through emotional, physical and financial support. It also means Fathers have a profound and lasting impact on their that men take joint responsibility with their partner for children’s development. As stated in the Nurturing Care the workload -including unpaid care work, child rearing, Framework (World Health Organization, 2018), parents and paid work outside the home – and foster a and caregivers are the most important providers -

Procrustean Motherhood: the Good Mother During Depression (1930S), War (1940S), and Prosperity (1950S) Romayne Smith Fullerton the University of Western Ontario

Western University Scholarship@Western FIMS Publications Information & Media Studies (FIMS) Faculty 2010 Procrustean Motherhood: The Good Mother during Depression (1930s), War (1940s), and Prosperity (1950s) Romayne Smith Fullerton The University of Western Ontario M J. Patterson Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Citation of this paper: Smith Fullerton, R. & Patterson, M.J “Procrustean Motherhood: The Good otheM r during Depression (1930s), War (1940s), and Prosperity (1950s)”. The aC nadian Journal of Media Studies. Volume 8, December 2010. Procrustean Motherhood 1 Procrustean Motherhood: The Good Mother during Depression (1930s), War (1940s), and Prosperity (1950s) Maggie Jones Patterson Duquesne University And Romayne Smith Fullerton University of Western Ontario Procrustean Motherhood 2 Abstract Women have long considered home making, parenting, and fashion magazines, addressed directly to them, to be a trusted source for advice and for models of behavior. This trust is problematic given that sample magazine articles from the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s show cultural portrayals of motherhood that appear more proscriptive than descriptive. They changed little, although real women’s roles in both the domestic and public realms were undergoing significant shifts. During these decades of Great Depression, World War II, and unprecedented post-war prosperity, women went to school and entered the workplace in growing numbers, changed their reproductive choices, and shifted their decisions to marry and divorce, living more of their lives independent of matrimony. All the while, popular culture’s discourse on the Good Mother held to the same sweet but increasingly stale portrait that failed to address the changes in women’s lives beyond the glossy page. -

Matrifocality and Women's Power on the Miskito Coast1

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast by Laura Hobson Herlihy 2008 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Herlihy, Laura. (2008) “Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast.” Ethnology 46(2): 133-150. Published version: http://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/index Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. MATRIFOCALITY AND WOMEN'S POWER ON THE MISKITO COAST1 Laura Hobson Herlihy University of Kansas Miskitu women in the village of Kuri (northeastern Honduras) live in matrilocal groups, while men work as deep-water lobster divers. Data reveal that with the long-term presence of the international lobster economy, Kuri has become increasingly matrilocal, matrifocal, and matrilineal. Female-centered social practices in Kuri represent broader patterns in Middle America caused by indigenous men's participation in the global economy. Indigenous women now play heightened roles in preserving cultural, linguistic, and social identities. (Gender, power, kinship, Miskitu women, Honduras) Along the Miskito Coast of northeastern Honduras, indigenous Miskitu men have participated in both subsistence-based and outside economies since the colonial era. For almost 200 years, international companies hired Miskitu men as wage- laborers in "boom and bust" extractive economies, including gold, bananas, and mahogany. -

Mother-Women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 “Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott Kelly Ann Masterson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Masterson, Kelly Ann, "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Kelly Ann Masterson entitled "“Taming the Maternal”: Mother-women and the Construction of the Maternal Body in Harriet Jacobs, Kate Chopin, and Evelyn Scott." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Katherine L. Chiles, William J. Hardwig Accepted -

Mandatory Birth Reporting for Birth Certificate - Mother/Parent

PATIENT IDENTIFICATION AREA MANDATORY BIRTH REPORTING FOR BIRTH CERTIFICATE - MOTHER/PARENT Confidential Information The following items are required to be collected according to Massachusetts’ law (M.G.L. Ch.111 §24B). The law also requires that hospitals report additional medical information related to births. This information is kept completely confidential and is used for public health and population statistics, medical research, and program planning. These items never appear on copies of the birth certificate issued to you or your child. Your information is most commonly combined with data from mothers throughout Massachusetts and the United States and is published in tables and charts that do not identify you personally. The information you provide lets planners know which cities or towns need better public health services and provides facts your doctor needs to know to deliver babies safely. For instance, you help local school departments project numbers of students to plan for your newborn’s education, you help researchers and doctors know what effect quitting smoking during pregnancy has on fetal development or which occupations may be hazardous during pregnancy, and you help health providers know which languages are spoken in their area to have translated materials ready. Your cooperation is urgently needed in order to compile accurate data about Massachusetts families and their newborns. This is the primary source of statistical information about Massachusetts births, which without your help would be unknown. Planners and medical providers use birth data to improve or create new programs and services for mothers and their newborns. Your privacy is taken very seriously. Individual data is never released without the express permission of the Commissioner of Public Health and only within very strict guidelines. -

Mother Nature? Yes. Ecofeminism and the Ethics of Care

Mother Nature? Yes. Ecofeminism and the Ethics of Care. Overview 1. What is ecofeminism? 2. What is the ethic of care? 3. Why are these two concepts important? 4. Why are they relevant? 5. How it can be apolitical and a force for individual and communal good. (ECO)FEMINISM • Ecology is the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. • Feminism is the advocacy of women's rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes. So… why ecofeminism? • The concept is a theoretical framework that can be complex because of its broad implications. However, the underlying theme and attitude is simple. • Ecofeminism attempts to expose the connection between the oppression and exploitation of women to that of the environment Ahuh… • The processes and harmful practices that exploit the environment overlap with the social structures that oppress women. • Why? Because we live in a capitalistic and patriarchal society that rewards exploitation and oppression for profit. Oh boy here we go again … •Wait !!! -This shouldn’t be seen as a political issue. As much as there is plenty to critique both about the capitalistic system and ecofeminism as a theoretical framework, ecofeminism offers a lens of respect and compassion for others as well as the environment we all live in and that should be a worldview we all should strive for. Ethics of Care • Carol Gilligan’s Ethics of Care provides a structure that the ideal of care is thus an activity of relationship, of seeing and responding to need, taking care of the world by sustaining the web of connection so that no one is left alone. -

Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies

Transfeminist Perspectives Edited by ANNE ENKE Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2012 by Temple University All rights reserved Published 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Transfeminist perspectives in and beyond transgender and gender studies / edited by Anne Enke. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4399-0746-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4399-0747-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4399-0748-1 (e-book) 1. Women’s studies. 2. Feminism. 3. Transgenderism. 4. Transsexualism. I. Enke, Anne, 1964– HQ1180.T72 2012 305.4—dc23 2011043061 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: Transfeminist Perspectives 1 A. Finn Enke Note on Terms and Concepts 16 A. Finn Enke PART I “This Much Knowledge”: Flexible Epistemologies 1 Gender/Sovereignty 23 Vic Muñoz 2 “Do Th ese Earrings Make Me Look Dumb?” Diversity, Privilege, and Heteronormative Perceptions of Competence within the Academy 34 Kate Forbes 3 Trans. Panic. Some Th oughts toward a Th eory of Feminist Fundamentalism 45 Bobby Noble 4 Th e Education of Little Cis: Cisgender and the Discipline of Opposing Bodies 60 A. Finn Enke PART II Categorical Insuffi ciencies and “Impossible People” 5 College Transitions: Recommended Policies for Trans Students and Employees 81 Clark A. -

Mother-To-Mother Support Groups

Mother-to-Mother Support Groups FACILITATor’S MANUAL WITH DISCUSSION GUIDE Photos: PATH/Evelyn Hockstein March 2011 This document was produced through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. GPO-A-00-06- 00008-00. The opinions herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development. For more information, please contact: The Infant & Young Child Nutrition PATH (IYCN) Project ACS Plaza, 4th Floor 455 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Suite 1000 Lenana Road Washington, DC 20001 USA P.O. Box 76634-00508 Tel: (202) 822-0033 Nairobi, Kenya Fax: (202) 457-1466 Tel: 254-20-3877177 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.iycn.org IYCN is implemented by PATH in collaboration with CARE; The Manoff Group; and University Research Co., LLC. Acknowledgments This manual was originally prepared by PATH in Kenya with funding support from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and technical review and oversight from the Kenya Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. The Infant & Young Child Nutrition (IYCN) Project updated this manual to reflect the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines on HIV and Infant Feeding. Content for this manual is based on several key mother-to-mother support and infant and young child feeding publications including: Training of Trainers for Mother-to-Mother Support Groups (LINKAGES) Behavior Change Communication for Improved Infant Feeding – Training of Trainers for Negotiating Sustainable Behavior Change (LINKAGES) Community-Based Breastfeeding Support: A Training Curriculum (Wellstart International) Infant Feeding Counselling: An Integrated Course (WHO/UNICEF) Preparation of Trainer’s Course: Mother-to-Mother Support Group Methodology, and Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Basics Instructional Planning Training Package. -

Harry T. Burn Newspaper Interview

HANDOUT D Harry T. Burn Newspaper Interview Directions: One or more students assigned as Newspaper Reporters should provide the background shown here in the form of an interview, as one student assigned to portray Harry T. Burn provides the responses shown below. Newspaper reporter mother, in his suit pocket. Harry Thomas Burn was a young Tennessee His intention was to lawyer first elected to his state legislature at vote to table the the age of 22. He was the youngest member question until the of the assembly, and in his first term he took next term, when he a courageous stand based on his conviction hoped that pro- that women have an inherent right to vote. suffrage opinion His quandary was that he represented a would have had very conservative county where anti-suffrage the opportunity sentiment dominated, and he hoped to win to grow in his re-election to another term as representative. county. However, Was it his duty to reflect the preference of his the vote to delay constituents and increase his chances of winning the question was the next election, or was it his duty to vote his tied at 48 – 48—twice. own conscience regarding the right of women to Finally, the speaker of the participate in their governance? house called for a vote on the By August of 1920, thirty-five of the forty- Amendment itself, rather than a vote to delay. eight state legislatures had voted to ratify The letter from his widowed mother, Febb E. the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteeing Burn, gained new significance. -

Antifeminism Online MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way)

Antifeminism Online MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way) Jie Liang Lin INTRODUCTION Reactionary politics encompass various ideological strands within the online antifeminist community. In the mass media, events such as the 2014 Isla Vista killings1 or #gamergate,2 have brought more visibility to the phenomenon. Although antifeminism online is most commonly associated with middle- class white males, the community extends as far as female students and professionals. It is associated with terms such as: “Men’s Rights Movement” (MRM),3 “Meninism,”4 the “Red Pill,”5 the “Pick-Up Artist” (PUA),6 #gamergate, and “Men Going Their Own Way” (MGTOW)—the group on which I focused my study. I was interested in how MGTOW, an exclusively male, antifeminist group related to past feminist movements in theory, activism and community structure. I sought to understand how the internet affects “antifeminist” identity formation and articulation of views. Like many other antifeminist 1 | On May 23, 2014 Elliot Rodger, a 22-year old, killed six and injured 14 people in Isla Vista—near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus—as an act of retribution toward women who didn’t give him attention, and men who took those women away from him. Rodger kept a diary for three years in anticipation of his “endgame,” and subscribed to antifeminist “Pick-Up Artist” videos. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/05/26/justice/ california-elliot-rodger-timeline/ Accessed: March 28, 2016. 2 | #gamergate refers to a campaign of intimidation of female game programmers: Zoë Quinn, Brianna Wu and feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian, from 2014 to 2015. -

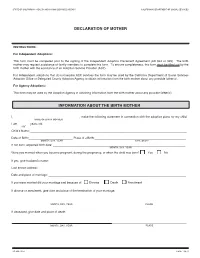

Declaration of Mother

STATE OF CALIFORNIA - HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES AGENCY CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SERVICES This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, use the Down Arrow from a form field. DECLARATION OF MOTHER INSTRUCTIONS: For Independent Adoptions: This form must be completed prior to the signing of the Independent Adoption Placement Agreement (AD 924 or 925). The birth mother may request assistance of family members to complete this form. To ensure completeness, this form must be filled out by the birth mother with the assistance of an Adoption Service Provider (ASP). For Independent adoptions that do not require ASP services the form may be used by the California Department of Social Services Adoption Office or Delegated County Adoption Agency to obtain information from the birth mother about any possible father(s). For Agency Adoptions: This form may be used by the Adoption Agency in obtaining information from the birth mother about any possible father(s). INFORMATION ABOUT THE BIRTH MOTHER I, ________________________________________, make the following statement in connection with the adoption plans for my child. NAME OF BIRTH MOTHER I am _______ years old. AGE Child’s Name:________________________________________________________________________________________________ Date of Birth:___________________________ Place of a Birth:________________________________________________________ MONTH, DAY, YEAR CITY, STATE If not born, expected birth date: _________________________________________________________________________________