Collaboration Engineering: Foundations and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PolyU Institutional Repository This is the Pre-Published Version. Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms Patrick S.W. Fong1 and Cecilia W.C. Kwok2 ABSTRACT This research focuses on contracting firms within the construction sector. It characterizes and evaluates the composition of organizational culture using four culture types (Clan, Adhocracy, Market, and Hierarchy), the strategic approach for knowledge flow, and the success of KM systems at different hierarchical levels of contracting organizations (project and parent organization level). Responses from managers of local or overseas contracting firms operating in Hong Kong were collected using a carefully constructed questionnaire survey that was distributed through electronic mail. The organizational value is analyzed in terms of the four cultural models. Clan culture is found to be the most popular at both project and organization levels, which means that the culture of contracting firms very much depends on honest communication, respect for people, trust, and cohesive relationships. On the other hand, Hierarchy 1 Associate Professor, Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong (corresponding author). T: +(852) 2766 5801 F: +(852) 2764 5131 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong. 1 culture, which focuses on stability and continuity, and analysis and control, seems to be the least favored at both levels. Another significant finding was that the two main KM strategies for knowledge flow, Codification and Personalization, were employed at both project and organization levels in equal proportion. -

Collaborative Engineering for Research and Development

NASA/TM—2004-212965 Collaborative Engineering for Research and Development José M. Davis Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio L. Ken Keys and Injazz J. Chen Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio February 2004 The NASA STI Program Office . in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to ∑ CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key part meetings sponsored or cosponsored by in helping NASA maintain this important role. NASA. The NASA STI Program Office is operated by ∑ SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, Langley Research Center, the Lead Center for technical, or historical information from NASA’s scientific and technical information. The NASA programs, projects, and missions, NASA STI Program Office provides access to the often concerned with subjects having NASA STI Database, the largest collection of substantial public interest. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional ∑ TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. English- mechanism for disseminating the results of its language translations of foreign scientific research and development activities. These results and technical material pertinent to NASA’s are published by NASA in the NASA STI Report mission. Series, which includes the following report types: Specialized services that complement the STI ∑ TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of Program Office’s diverse offerings include completed research or a major significant creating custom thesauri, building customized phase of research that present the results of databases, organizing and publishing research NASA programs and include extensive data results . even providing videos. -

Managing Design and Construction Using Systems Engineering for Use with DOE O 413.3A

NOT MEASUREMENT SENSITIVE DOE G 413.3-1 9-23-08 Managing Design and Construction Using Systems Engineering for Use with DOE O 413.3A [This Guide describes suggested nonmandatory approaches for meeting requirements. Guides are not requirements documents and are not construed as requirements in any audit or appraisal for compliance with the parent Policy, Order, Notice, or Manual.] U.S. Department of Energy Washington, D.C. 20585 AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: INITIATED BY: www.directives.doe.gov National Nuclear Security Administration DOE G 413.3-1 i 9-23-08 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Goal .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Applicability. .................................................................................................................... 2 1.3. What is Systems Engineering? ......................................................................................... 2 1.4. Links with Other Directives ............................................................................................. 2 1.5. Overlapping Systems Engineering and Safety Principles and Practices .......................... 4 1.6. Differences in Terminology ............................................................................................. 5 1.7. How this Guide is Structured .......................................................................................... -

Engineering Management - M.S

Engineering Management - M.S. Leading and managing projects in a technical environment needs qualied MGMT6340 Lean Production and Quality Control professionals who possess a blend of analytical and project management Total Credits 30-33 credits skills combined with an understanding of engineering processes and product * Students without evidence of coursework in programming from at least a bachelor's degree development. level program will need to take this course prior to taking core courses. The online Engineering Management Master of Science degree program ** Students can choose any combination of three courses that they have prerequisites for from is an interdisciplinary program that integrates the elds of engineering, the listing of Data Analytics, Finance, or Operations and Supply Chain Management courses, technology and business. It is designed for engineering and other STEM to earn the MS Engineering Management degree. (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) related bachelor’s degree recipients as well as professionals in the eld with bachelor’s degrees in business who are seeking to take on leadership and management roles in a technology environment. The program includes core courses in statistical analysis, nance, decision making, leadership and innovation, new product development, and project management principles for the engineering and technology industry. In this program, students gain the theoretical, quantitative and analytical skills and tools they will need to be an effective leader of an engineering management team. The Engineering Management Master of Science degree program emphasizes management and leadership skills specically for the engineering and technology industry. Students use electives to tailor their degree to their interest. Electives can also be chosen to create a focus area in either Data Analytics, Finance or Operations & Supply Chain Management. -

Engineering Management Graduate Program

More Information ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT STUDENT ADVISER Denise Engebrecht [email protected] Engineering Management (208) 364-6123 Graduate Program INTEGRATING ENGINEERING & BUSINESS INTEGRATING ENGINEERING & BUSINESS www.uidaho.edu/engr/engineeringmanagement Program Why an Engineering Management Program Delivery Advising Outcomes Graduate Degree? Faculty and instructors teach courses at U of I locations in Moscow, Idaho You will work with the student adviser to build a unique study • To expand and reinforce your Falls, and Boise. Courses may be delivered live, online via the web, or produced Bridging the Gap between Engineering and Business plan around a set of core courses existing engineering skill set for online delivery by Engineering Outreach (EO). EO courses are accessible that allows you to meet your Engineering Management is a multidisciplinary field that involves the within 2 hours of production. If you want the flexibility to watch classes at your career objectives. • To thoroughly examine the convenience, this program can meet your needs. roles and responsibilities of an application of engineering methods and technologies with business engineering manager approaches to solve today’s complex and challenging problems. This program bridges the gap between engineering and business by equipping engineers with Engineering Management Degree Good Career • To provide you with a solid the expertise and leadership skills needed to advance their career in today’s Opportunities foundation in engineering Requirements fast-paced world. Students will expand their breadth of knowledge beyond a Engineering managers are #6 on management and business The Engineering Management master’s degree requires 30 credits; a minimum the top 20 list of best paying jobs approaches, tools and practices specific technical field into management and business. -

Strategic Plan for Industrial and Management Systems Engineering

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Industrial and Management Systems Industrial and Management Systems Engineering -- Reports Engineering 8-2008 Strategic Plan For Industrial and Management Systems Engineering Paul Savory University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/imsereports Part of the Industrial Engineering Commons Savory, Paul, "Strategic Plan For Industrial and Management Systems Engineering" (2008). Industrial and Management Systems Engineering -- Reports. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/imsereports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Industrial and Management Systems Engineering at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Industrial and Management Systems Engineering -- Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STRATEGIC PLAN INDUSTRIAL and MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS ENGINEERING ROLE OF THIS PLAN The role of this strategic plan is to map out a range of department goals, offer objectives for achieving each goal, and list potential strategies for meeting an objective. It also lists performance metrics for measuring progress for each goal. Each year, a subset of goals and objectives will be identified by the IMSE department as a priority for the coming year. Detailed metrics for measuring improvement for the department’s priorities areas will then be defined. DEPARTMENT MISSION The mission of the department is to advance the frontiers of industrial engineering, to educate qualified individuals in the discipline, and to disseminate knowledge both within and beyond the university for applying industrial engineering concepts and principles to technical and societal challenges. -

Collaboration Engineering: Foundations And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Special Issue Collaboration Engineering: Foundations and stems stems y Opportunities: Editorial to the Special Issue on the Journal of the Association of Information Systems Gert-Jan de Vreede Anne P. Massey Center for Collaboration Science Indiana University University of Nebraska at Omaha [email protected] and Delft University of Technology [email protected] Robert O. Briggs Center for Collaboration Science University of Nebraska at Omaha [email protected] Abstract Collaboration is a critical phenomenon in organizational life. Collaboration is necessary yet many organizations struggle to make it work. The field of IS has devoted much effort to understanding how technologies can improve the productivity of collaborative work. Over the past decade, the field of Collaboration Engineering has emerged as a focal point for research on designing and deploying collaboration processes that are recurring in nature and that are executed by practitioners in organizations rather than collaboration professionals. In Collaboration Engineering, researchers do not study a collaboration technology in isolation. Rather, they study collaborative work practices that can be supported on different technological platforms. In this editorial, we discuss the field of Collaboration Engineering in terms of its foundations, its approach to designing and deploying collaboration processes, and its modeling techniques. We conclude with a Collaboration Engineering research agenda for the coming decade. Journal of the Association for Information S Journal of the Association Volume 10, Special Issue, pp. 121-137, March 2009 Volume 10 Special Issue Article 2 Collaboration Engineering: Foundations and Opportunities 1. -

Decision Making in Engineering Management

Decision Making in Engineering Management John Murdoch, University of York Antony Powell, YorkMetrics 24th June 2009 PSM 2010/ Julyyp 08 Workshop Performance Information Enterprise Project Needs Objective Integrated Fact-Based Management Data Analysis Decisions Actions Measurement Application Decision Environment • Capable Information Process • Decision “Freedom” • Viable Measurement Constructs • Decision - Change Implementation • Both Measurement and Risk Data • Performance Tradeoff Decisions • Performance Analysis • Measureable Performance Feedback • Decision Alternatives • Integrated Context - Portfolio Mgt. • Unfettered Communication • Revised Strategies and Objectives Source: PSM Project Decision Makers SUPPLIERS SUPPLIER MANAGERS REGULATORS SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT ACQUISITION CERTIFICATION MANAGER AND COMPLIANCE PROJECT DESIGN MANAGER AUTHORITY COMPLIANCE MANAGEMENT CHIEF ENGINEER FUNDERS ENTERPRISE PROJECT MANAGERS DECISION CONFIG MAKING CONTROL COMMERCIAL ENTERPRISE MANAGERS ASSURANCE MANAGEMENT ENGINEERING MANAGER SYSTEMS ENGINEERS SPECIALTY CUSTOMERS ENGINEERS SOFTWARE COMPONENT ENGINEERS ENGINEERS 309 00 ENGINEERING END USERS 0102 MANAGEMENT Source: SSEI Motivation and Objectives ■ Complex defense projects often perform poorly from external perspectives ■ Engineering perspective: strive to develop and support products that are fit for purpose and that use resources as efficiently as possible ■ Hypothesis: better su pport and promotion of the en gineerin g view, integrated through supply chains and through the lifecycle, will -

The Effect of the Harmony Between Organizational Culture and Values on Job Satisfaction

International Business Research; Vol. 10, No. 5; 2017 ISSN 1913-9004 E-ISSN 1913-9012 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Effect of the Harmony between Organizational Culture and Values on Job Satisfaction Erkan Taşkıran1, Canan Çetin2, Ata Özdemirci2, Baki Aksu 3, Meri İstoriti4 1School of Tourism Administration and Hotel Management, Düzce University, Düzce, Turkey 2Faculty of Business Administration, Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey 3Vocational School of Logistics, Beykoz University, Istanbul, Turkey 4Liv Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey Correspondence: Erkan Taşkıran, School of Tourism Administration and Hotel Management, Düzce University, Osmaniye Mahallesi, Atatürk Caddesi, No.221 Akçakoca, 81650, Düzce, Turkey. Received: March 13, 2017 Accepted: April 19, 2017 Online Published: April 24, 2017 doi:10.5539/ibr.v10n5p133 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v10n5p133 Abstract In this study, the effect of the harmony between organizational culture and values on job satisfaction is examined. Hierarchical regression analysis was applied to the data, which was obtained from the study conducted on 181 employees working in a private hospital in Istanbul. The result of the analysis shows that value-culture variation in which employees will have the highest job satisfaction is the traditionalist/conservative values-clan culture. The second most successful value-culture variation on job satisfaction is the impulsive/hedonistic values-adhocracy culture. In other words, it is predicted that job satisfaction will be high when an employee with traditionalist/conservative values works in an organization where clan culture is important, and an employee with impulsive/hedonistic values works in an organization where adhocracy culture is important. The most negative impacts on job satisfaction are impulsive/hedonistic values-clan culture and precautionary values-market culture. -

Innovation Forecasting: a Case Study of the Management of Engineering and Technology Literature

Technological Forecasting & Social Change 78 (2011) 346–357 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Technological Forecasting & Social Change Innovation forecasting: A case study of the management of engineering and technology literature Scott W. Cunningham ⁎, Jan Kwakkel Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands article info abstract Article history: The following paper contributes to the methodology of innovation forecasting. The paper Received 16 December 2009 analyzes the literature of engineering and technology management. A brief history and Received in revised form 1 November 2010 justification for interest in engineering and technology management is presented. The field has Accepted 5 November 2010 a sixty year history of interdisciplinary, and is therefore a ripe source for closer investigation into time trends of knowledge. The paper reviews the literature of innovation forecasting, Keywords: examining a range of theoretical and methodological literatures interested in the evolution Innovation forecasting of knowledge. A new application of a model, suitable for sparse and count-like publication Management of technology data, is presented. A mathematical presentation of the model is offered. A discussion is offered Engineering management on how the model may be implemented in an approachable way within spreadsheet software. Time series analysis A time history of engineering management literature is extracted from a database and analyzed Spreadsheets Probability models using the model. A projection of keyword growth is offered, and key features of the emerging knowledge base within engineering management are discussed. Recommendations for future research, as well as for those monitoring the status of the discipline of engineering management, are made. -

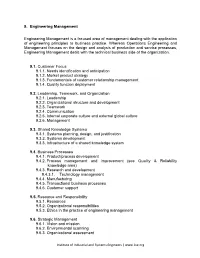

9. Engineering Management

9. Engineering Management Engineering Management is a focused area of management dealing with the application of engineering principles to business practice. Whereas Operations Engineering and Management focuses on the design and analysis of production and service processes, Engineering Management deals with the technical business side of the organization. 9.1. Customer Focus 9.1.1. Needs identification and anticipation 9.1.2. Market product strategy 9.1.3. Fundamentals of customer relationship management 9.1.4. Quality function deployment 9.2. Leadership, Teamwork, and Organization 9.2.1. Leadership 9.2.2. Organizational structure and development 9.2.3. Teamwork 9.2.4. Communication 9.2.5. Internal corporate culture and external global culture 9.2.6. Management 9.3. Shared Knowledge Systems 9.3.1. Systems planning, design, and justification 9.3.2. Systems development 9.3.3. Infrastructure of a shared knowledge system 9.4. Business Processes 9.4.1. Product/process development 9.4.2. Process management and improvement (see Quality & Reliability knowledge area) 9.4.3. Research and development 9.4.3.1. Technology management 9.4.4. Manufacturing 9.4.5. Transactional business processes 9.4.6. Customer support 9.5. Resource and Responsibility 9.5.1. Resources 9.5.2. Organizational responsibilities 9.5.3. Ethics in the practice of engineering management 9.6. Strategic Management 9.6.1. Vision and mission 9.6.2. Environmental scanning 9.6.3. Organizational assessment Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers | www.iise.org 9.6.4. The planning process 9.6.5. Goals, objectives, targets, and measures 9.6.6. -

Decision Making in Systems Engineering and Management Decision Making in Systems Engineering and Management

DECISION MAKING IN SYSTEMS ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT DECISION MAKING IN SYSTEMS ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT Second Edition Edited by GREGORY S. PARNELL PATRICK J. DRISCOLL DALE L. HENDERSON A JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC., PUBLICATION Copyright © 2011 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation.