Designedinthe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole Document

Copyright By Christin Essin Yannacci 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Christin Essin Yannacci certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 Committee: _______________________________ Charlotte Canning, Supervisor _______________________________ Jill Dolan _______________________________ Stacy Wolf _______________________________ Linda Henderson _______________________________ Arnold Aronson Landscapes of American Modernity: A Cultural History of Theatrical Design, 1912-1951 by Christin Essin Yannacci, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Acknowledgements There are many individuals to whom I am grateful for navigating me through the processes of this dissertation, from the start of my graduate course work to the various stages of research, writing, and editing. First, I would like to acknowledge the support of my committee members. I appreciate Dr. Arnold Aronson’s advice on conference papers exploring my early research; his theoretically engaged scholarship on scenography also provided inspiration for this project. Dr. Linda Henderson took an early interest in my research, helping me uncover the interdisciplinary connections between theatre and art history. Dr. Jill Dolan and Dr. Stacy Wolf provided exceptional mentorship throughout my course work, stimulating my interest in the theoretical and historical complexities of performance scholarship; I have also appreciated their insights and generous feedback on beginning research drafts. Finally, I have been most fortunate to work with my supervisor Dr. Charlotte Canning. From seminar papers to the final drafts of this project, her patience, humor, honesty, and overall excellence as an editor has pushed me to explore the cultural implications of my research and produce better scholarship. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Building Cultures by Designing Buildings: Corporatism, Eero Saarinen, and Thevivian Beaumont Repertory Theater at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

85TH ACSA ANNUAL MEETING ANDTECHNOLOGY CONFERENCE 457 Building Cultures by Designing Buildings: Corporatism, Eero Saarinen, and theVivian Beaumont Repertory Theater at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts WESLEY R. JANZ, AIA Ball State University In 1964, the inaugural production of the Lincoln Center the temporary facility. The second considers the architec- repertory company opened to critical acclaim. The debut of tural intentions of these non-architects as they gave physical Arthur Miller's play After The Fall was "an impressive start" form to the preeminent culture they envisioned. (chapman); one that would "arouse an audience and enrich a season" (Nadel). The cast, which included Faye Dunaway, THE CAMPUS OF THE LINCOLN CENTER FOR Hal Holbrook, and leading man Jason Robards, Jr. was THE PERFORMING ARTS lauded: "no performance was less than compelling," stated Lincoln Center was the focus of the eighteen-block Lincoln Howard Taubman, the theater critic of the New York Times. Square Urban Redevelopment Project on the Upper West The theater, a temporary facility that was designed and Side of New York City. Spearheading the Lincoln Center built under the guidance of co-producing directors Robert component were Coinmissioner Robert Moses, Dwight Whitehead and Elia Kazan, was also praised. The critic John Eisenhower, the President of the United States; Nelson A. McClain termed the playhouse "a quite fabulous structure," Rockefeller, the Governor of the State of New York; and the and Howard Clunnan agreed; "the moment you enter it your third John D. Rockefeller. The Center's unofficial title, the attention is riveted on the stage" (Hyams). -

Oscar®-Nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at 19Th Annual Art Directors Guild Awards on January 31, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OSCAR®-NOMINATED PRODUCTION DESIGNER JIM BISSELL TO RECEIVE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT 19TH ANNUAL ART DIRECTORS GUILD AWARDS ON JANUARY 31, 2015 LOS ANGELES, July 15, 2014 — Emmy®-winning and Oscar®-nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell will receive the Art Directors Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award at the 19th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards on January 31, 2015 at a black- tie ceremony at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The announcement was made today by John Shaffner, ADG Council Chairman, and ADG Award Producers Dave Blass and James Pearse Connelly. “Jim Bissell’s work as a Production Designer is legendary and we are proud to rank him among the best in the history of our profession. He is an extraordinary artist and accomplished leader in the industry and it is our pleasure to name him as this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award recipient,” said Shaffner. A veteran leader of the ADG, Bissell was a past Vice President and a Board member for more than 15 years. He also chaired the Guild’s Awards Committee for the first three years of its existence. Bissell’s distinguished work can be seen on such notable films as E.T. the Extra- Terrestrial (1982), which took home four Oscars® with an additional five Oscar® nominations in 1983; The Rocketeer (1991), Jumanji (1995), 300 (2006), Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011) and most recently The Monuments Men (2014), directed by and starring George Clooney. Monuments Men is Jim’s fourth collaboration with Clooney, which began with Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), followed with Oscar®-nominated Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) and continuing with Leatherheads (2007). -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Acquisitions Edited.Indd

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

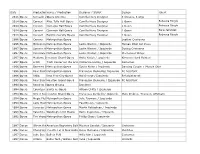

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

Introduction

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE OLIVE WONG PROJECT PERFORMANCE COSTUME DESIGN RESEARCH GUIDE INTRODUCTION COSTUME DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE WRITTEN AND EDITED BY AILEEN ABERCROMBIE The New York Public Library for the Perform- newspapers, sketches, lithographs, poster art ing Arts, located in Lincoln Center Plaza, is and photo- graphs. In this introduction, I will nestled between four of the most infuential share with you some of Olive’s selections from performing arts buildings in New York City: the NYPL collection. Avery Fisher Hall, Te Metropolitan Opera, the Vivian Beaumont Teater (home to the Lincoln There are typically two ways to discuss cos- Center Teater), and David H. Koch Teater. tume design: “manner of dress” and “the history Te library matches its illustrious location with of costume design”. “Manner of dress” contextu- one of the largest collections of material per- alizes the way people dress in their time period taining to the performing arts in the world. due to environment, gender, position, economic constraints and attitude. Tis is essentially the The library catalogs the history of the perform- anthropological approach to costume design. ing arts through collections acquired by notable Others study “the history of costume design”, photographers, directors, designers, perform- examining the way costume designers interpret ers, composers, and patrons. Here in NYC the the manner of dress in their time period: where so many artists live and work we have the history of the profession and the profession- an opportunity, through the library, to hear als. Tis discussion also talks about costume sound recording of early flms, to see shows designers’ backstory, their process, their that closed on Broadway years ago, and get to relationships and their work. -

City Theatrical Talks with Eastern Lighting Design's Matt Gordon and Mick Smith

A Conversation With MATT GORDON & MICK SMITH Nexstar Media Group’s “NewsNation” on WGN America in Chicago, Illinois Set Design: Clickspring Design | Lighting Design: Eastern Lighting Design | Lighting Package: Barbizon Fabrication: Chicago Scenic Studios, Inc.; Showman Fabricators | Display Technology: AOTO BACKGROUND Eastern Lighting Design is a leading international design firm specializing in broadcast, location, and special events lighting. With a keen eye on the latest technology and industry trends, lighting designers and entrepreneurs Matt Gordon and Mick Smith have taken the industry by storm, designing innovative news studios in Dubai, Chicago, Beijing, and everywhere in between. City Theatrical talked with the team about the design and technology that has gone into some of the projects of this budding company’s past, present, and future, in this designer interview. Q&A: York at Purchase, which had a really great a story through lighting. If you flip through conservatory for theatre arts and film. At the television channels, you know what you’re City Theatrical (CTI): How did you get time, it had the highest turnout for Broadway looking at without stopping to read the guide. started in the world of professional lighting designers of any school in the country. Lighting helps you easily identify the content lighting design? Initially, that’s where I was headed. and aesthetic you’re looking for. Matt Gordon (Matt): For me, lighting really I graduated Purchase, and did a lot of theatre. Mick Smith (Mick): Funny enough, my story is the only thing I’ve ever done. I started I landed on one Broadway show as an is almost identical to Matt’s.