The Illusion and Reality of Anti-Modi Wave in the Punjab 2019 General Election: a Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parkash Singh Badal by : INVC Team Published on : 30 Aug, 2015 05:00 PM IST

Talwandi's contribution for panth, punjab & punjabiat enormous : Parkash Singh Badal By : INVC Team Published On : 30 Aug, 2015 05:00 PM IST INVC NEWS Ludhiana, The first 'Barsi Samagam' of Senior Akali leader and former president of Shiromani Gurudwara Parbandhak Committee was organised at Gurudwara Tahliana Sahib, here today which was attended by Punjab CM Mr Parkash Singh Badal and a large number of personalities from different walks of life. While speaking on the occasion, CM Mr Parkash Singh Badal praised Jathedar Jagdev Singh Talwandi for his enormous contribution towards Panth, Punjab and Punjabiat. Mr. Badal said that the life and struggle of Jathedar Talwandi would ever act as a lighthouse for the coming generations to serve the state and the Panth with utmost zeal, sincerity and commitment. He said that probably Jathedar Talwandi was the only political leader who had served the state socially, politically and even religiously by being the President of Shiromani Akali Dal and Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee besides being a Member of Parliament and MLA of the state assembly. Badal said that with the death of Jathedar Talwandi a void has been created which would be difficult to fill in the near future. Recalling the outstanding services rendered by Jathedar Talwandi during the landmark agitations like Punjabi Suba, Emergency, Dharam Yudh and others, the Chief Minister said that the Jathedar Talwandi was a fearless leader who never comprised with the interests of the state and Panth. Describing Jathedar Talwandi as a decisive leader, Mr. Badal said that he never hesitated to take any bold decision if it was in the interest of Punjab and its people. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information __________________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL NOTE ….. ADDRESSES - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the Inaugural Event of the Eighth Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific on 10 April 2018 at Indore ARTICLES - Somnath Chatterjee - the Legendary Speaker By Devender Singh Aswal PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES … PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL … DEVELOPMENTS SESSIONAL REVIEW State Legislatures … RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST … APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted by the … Parliamentary Committees of Lok Sabha during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 II. Statement showing the work transacted by the … Parliamentary Committees of Rajya Sabha during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures … Of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament … and assented to by the President during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States … and the Union Territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union … and State Governments during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha … and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories ADDRESS BY THE SPEAKER, LOK SABHA, SMT. SUMITRA MAHAJAN AT THE INAUGURAL EVENT OF THE EIGHTH REGIONAL 3R FORUM IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC HELD AT INDORE The Eighth Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific was held at Indore, Madhya Pradesh from 10 to 12 April 2018. -

Why New Delhi and Islamabad Need to Get Stakeholders on Board

India-Pakistan Relations Why New Delhi and Islamabad Need to Get Stakeholders on Board Tridivesh Singh Maini Jan 1, 2016 Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif, at a meeting in Lahore on December 25, 2015. Photo: PTI Interest in Pakistan cuts across party affiliations in the Indian Punjab. It is much the same story on the other side though the Pakistani Punjab is often hamstrung by political and military considerations. The border States in India and Pakistan have business, cultural and familial ties that must be harnessed by both governments to push the peace process, says Tridivesh Singh Maini. Prime Minister, Narendra Modi’s impromptu stopover at Lahore on December 25, 2015, on his way back from Moscow and Kabul, caught the media not just in India and Pakistan, but also outside, by surprise. (Though the halt was ostensibly to wish Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on his birthday, the real import was hardly lost on Indo-Pak watchers) 1 . Such stopovers are a done thing in other parts of the world, especially in Europe. Yet, if Modi’s unscheduled halt was seen as dramatic and as a possible game changer, it was in no small measure due to the protracted acrimony between the neighbours, made worse by mutual hardening of stands post the Mumbai attack. In the event, the European style hobnobbing seemed to find favour with both PMs and as much is suggested by this report in The Indian Express 2 . However, such spontaneity is not totally alien in the Indo-Pak context. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s invitation to his counterpart, Yousuf Raza Gilani, for the World Cup Semi-final 2011, which faced domestic criticism was one such gesture 3 . -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES PROCEDURAL MATTERS PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha Rajya Sabha State Legislatures RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Seventeenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 250th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITES ______________________________________________________________________________ CONFERENCES AND SYMPOSIA 141st Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU): The 141st Assembly of the IPU was held in Belgrade, Serbia from 13 to 17 October, 2019. An Indian Parliamentary Delegation led by Shri Om Birla, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and consisting of Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Ms. Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Smt. -

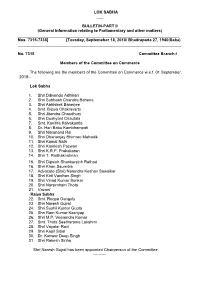

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Theparliamentarian

th 100 anniversary issue 1920-2020 TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2020 | Volume 101 | Issue One | Price £14 SPECIAL CENTENARY ISSUE: A century of publishing The Parliamentarian, the Journal of Commonwealth Parliaments, 1920-2020 PAGES 24-25 PLUS The Commonwealth Building Commonwealth Votes for 16 year Promoting global Secretary-General looks links in the Post-Brexit olds and institutional equality in the ahead to CHOGM 2020 World: A view from reforms at the Welsh Commonwealth in Rwanda Gibraltar Assembly PAGE 26 PAGE 30 PAGE 34 PAGE 40 CPA Masterclasses STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance, and Online video Masterclasses build an informed implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. parliamentary community across the Commonwealth Calendar of Forthcoming Events and promote peer-to-peer learning 2020 Confirmed as of 24 February 2020 CPA Masterclasses are ‘bite sized’ video briefings and analyses of critical policy areas March and parliamentary procedural matters by renowned experts that can be accessed by Sunday 8 March 2020 International Women's Day the CPA’s membership of Members of Parliament and parliamentary staff across the Monday 9 March 2020 Commonwealth Day 17 to 19 March 2020 Commonwealth Association of Public Accounts Committees (CAPAC) Conference, London, UK Commonwealth ‘on demand’ to support their work. April 24 to 28 April 2020 -

Lm+D Ifjogu Vksj Jktekxz Ea=H Be Pleased to State

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 5468 ANSWERED ON 25TH JULY, 2019 CONSTRUCTION OF ROADS UNDER CRF IN PUNJAB 5468. SHRI RAVNEET SINGH BITTU: DR. AMAR SINGH: Will the Minister of ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS lM+d ifjogu vkSj jktekxZ ea=h be pleased to state: (a) whether the Union Government has received proposals from the Government of Punjab for construction of roads under Central Road Fund (CRF) and to undertake new highway projects; (b) if so, the details thereof along with the action taken thereon during the last three years and the current year; (c) the details of roads approved and funds released from CRF during the said period; and (d) the present status of these road projects? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND HIGHWAYS (SHRI NITIN JAIRAM GADKARI) (a) to (d) The details of proposals approved during the last three years in the State of Punjab under Central Road Fund (CRF) along with the present status of these projects are given at Annexure. With the amendment of CRF Act, 2000, through Finance Act, 2018 and replacing the earlier Act with new Act viz. 'Central Road and Infrastructure Fund Act, 2000', sanction of schemes for the State Roads is no longer a function of the Central Government. The funds released under CRF to the State of Punjab during the last three years and current year are given below:- Financial Year Funds released in Rs. crore 2016-17 71.30 2017-18 162.68 2018-19 170.11 2019-20 54.74 ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) to (d) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. -

Lok Sabha ___ Bulletin – Part I

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN – PART I (Brief Record of Proceedings) ___ Tuesday, June 18, 2019/Jyaistha 28, 1941(Saka) ___ No. 2 11.00 A.M. 1. Observation by the Speaker Pro tem* 11.03 A.M. 2. Oath or Affirmation The following members took the oath or made the affirmation, signed the Roll of Members and took their seats in the House:- Sl. Name of Member Constituency State Oath/ Language No. Affirmation 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. Shri Santosh Pandey Rajnandgaon Chhattisgarh Oath Hindi 2. Shri Krupal Balaji Ramtek(SC) Maharashtra Oath Marathi Tumane 3. Shri Ashok Mahadeorao Gadchiroli-Chimur Maharashtra Oath Marathi Nete (ST) 4. Shri Suresh Pujari Bargarh Odisha Oath Odia 5. Shri Nitesh Ganga Deb Sambalpur Odisha Oath English 6. Shri Er. Bishweswar Mayurbhanj (ST) Odisha Oath English Tudu 7. Shri Ve. Viathilingam Puducherry Puducherry Oath Tamil 8. Smt. Sangeeta Kumari Bolangir Odisha Oath Hindi Singh Deo 9. Shri Sunny Deol Gurdaspur Punjab Oath English *Original in Hindi, for details, please see the debate of the day. 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 10. Shri Gurjeet Singh Aujla Amritsar Punjab Oath Punjabi 11. Shri Jasbir Singh Gill Khadoor Sahib Punjab Affirmation Punjabi (Dimpa) 12. Shri Santokh Singh Jalandhar (SC) Punjab Oath Punjabi Chaudhary 13. Shri Manish Tewari Anandpur Sahib Punjab Oath Punjabi 14. Shri Ravneet Singh Bittu Ludhiana Punjab Oath Punjabi 15. Dr. Amar Singh Fatehgarh Sahib Punjab Oath Punjabi (SC) 16. Shri Mohammad Faridkot (SC) Punjab Oath Punjabi Sadique 17. Shri Sukhbir Singh Badal Firozpur Punjab Oath Punjabi 18. Shri Bhagwant Mann Sangrur Punjab Oath Punjabi 19. -

Centre Prohibits Exports of Remdesivir

WWW.YUGMARG.COM FOLLOW US ON REGD NO. CHD/0061/2006-08 | RNI NO. 61323/95 Join us at telegram https://t.me/yugmarg Monday April 12, 2021 CHANDIGARH, VOL. XXVI, NO. 72 PAGES 8, RS. 2 YOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER New sugarcane Human noises are Will impose After getting mill working well: altering ocean lockdown if dropped during condition MD landscape Australia tour, I in hospitals worked hard on worsens: Kejriwal myself: Shaw PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 7 PAGE 8 India observes 'Tika Utsav' Centre prohibits exports of Remdesivir AGENCY to curb spreading of corona NEW DELHI, APRIL 11 Rahul Gandhi The Centre on Sunday prohibited ex- AGENCY States across the country ports of injection Remdesivir and to campaign in NEW DELHI, APRIL 11 from Madhya Pradesh to Tamil Remdesivir Active Pharmaceutical West Bengal Nadu ramped up their efforts to Ingredients (API) till the Covid-19 With an aim to vaccinate maxi- increase the vaccination process. situation in the country improves. from April 14 mum number of eligible people Manipur Chief Minister N Remdesivir is considered a key NEW DELHI: Congress against COVID-19, India on Sun- Biren Singh took his first dose of anti-viral drug in the fight against leader Rahul Gandhi will day launched the four-day-long the COVID-19 vaccine on Sun- Covid-19. In addition, the govern- begin campaigning in 'Tika Utsav' or vaccination festi- day at the launch of 'Tika Utsav' ment has taken three steps to ensure West Bengal from April 14 and address rallies in val. in Imphal's Jawaharlal Nehru In- easy access of hospitals and patients Goalpokhar and Mati- Prime Minister Narendra stitute of Medical Sciences. -

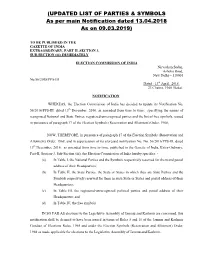

UPDATED LIST of PARTIES & SYMBOLS As Per Main Notification Dated 13.04.2018 As on 09.03.2019

(UPDATED LIST OF PARTIES & SYMBOLS As per main Notification dated 13.04.2018 As on 09.03.2019) TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY, PART II, SECTION 3, SUB-SECTION (iii) IMMEDIATELY ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 No.56/2018/PPS-III Dated : 13th April, 2018. 23 Chaitra, 1940 (Saka). NOTIFICATION WHEREAS, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2016/PPS-III, dated 13th December, 2016, as amended from time to time, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968; NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid notification No. No. 56/2016/PPS-III, dated 13th December, 2016, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extra-Ordinary, Part-II, Section-3, Sub-Section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies: - (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. IN SO FAR AS elections to the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir are concerned, this notification shall be deemed to have been issued in terms of Rules 5 and 10 of the Jammu and Kashmir Conduct of Elections Rules, 1965 and under the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968 as made applicable for elections to the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. -

Lastweekofhousesession,Nosignof Thaw

DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 2021, KOLKATA, LATE CITY, 12 PAGES SINCE 1932 `5.00/EX-KOLKATA `6.00(`12INNORTH EAST STATES&ANDAMAN)WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM OBC BILL COMING UP, CONG SAYS WON’T OPPOSE WORLD LastweekofHousesession,nosignof thaw,OppwantstobeheardonPegasus TALIBAN SEIZE KUNDUZ, AKEY AFGHANCITY Tharoor says time forno-trustmotion; 72 seconds out of 45 min: Lok Sabha TV PAGE 10 TMC putsout video of Opp in House coverage of Opp in House last sitting Shashi Tharoor said the BUSINESSASUSUAL MANOJCG Opposition should nowmove a farm laws that triggered the NEWDELHI,AUGUST8 no-confidence motion against LIZMATHEW& farmer agitation, says itsprotests BY UNNY the Government. “Rather than HARIKISHANSHARMA areonlyshown on screens inside AS THIS Monsoon sessionof justcontinuing disruptions, we NEWDELHI,AUGUST8 the House, and notbeamed Parliament enters itsfinal week, should probablyseriouslycon- across the country. there is little possibilityofboth siderother parliamentary ma- SCHEDULED TO end August13, On Friday, when Lok Sabha the Houses functioning smoothly noeuvres…including avoteof Parliament’s monsoonsession lastmet,LSTVshowed as Opposition parties Sunday no-confidence, because Ithink hasbeen disruptedbythe row Opposition protestsfor all of 72 made it clear they willcontinue thereisgenuinelynoconfidence over allegedsurveillancethrough seconds –House proceedings to insistonadiscussion on the among the bulk of the the use of the Pegasus spyware. lastedatotal of 45 minutes over Pegasus spywareissue—ade- Opposition parties in this Accusing Lok Sabha TV of twosittings that day. Despite red flags, Rly mand that the Government is Government,” Tharoor told The shutting it out, the Opposition, Friday, 11.07am. Oppn MPs OppositionMPs, however, unlikelytoaccede to. -

As on 30-09-2020

GRAPH-PERCENTAGE UTILISATION OF FUNDS UPTO 30.09.2020 SITTING/EX MPs BOTH LS AND RS SINCE INCEPTION(1993-94)(ITEM 2.1) 1 2 5 100.00 9 9 . 3 5 9 7 . 3 4 9 7 . 3 0 9 6 . 8 5 1 0 0 9 5 . 4 5 9 4 . 4 7 9 4 . 1 4 9 4 . 1 0 9 3 . 9 5 9 3 . 6 9 9 2 . 4 9 9 2 . 1 5 9 1 . 8 8 9 1 . 7 6 9 1 . 5 0 8 6 . 5 9 75 % UTILISATION % 50 25 0 ITEM 1.1 : INSTALLMENTS DUE - 16TH LS MPs As on 30/09/2020 SN Districts 2017-18 (1st) 2017-18 (2nd) 2018-19 (1st) 2018-19(2nd) Total 1 Amritsar-Gurjeet Singh ----0 2 Bathinda-Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal ----0 3 Faridkot-Sh. Sadhu Singh (SC) ----0 4 Ferozepur-Sh. Sher Singh Ghubaya ----0 Gurdaspur- Sunil Jakhar 5 --112 6 Hoshiarpur-Sh. Vijay Sampla (SC) ---11 7 Jalandhar-Sh. Santokh Singh Chaudhary ----0 8 Ludhiana-Sh. Ravneet Singh Bittu ----0 9 Patiala-Sh. Dharam Vira Gandhi ----0 10 Sangrur-Sh. Bhagwant Mann ----0 11 Ludhiana-Sh. Harinder Singh khalsa( Fatehgarh Sahib) ----0 12 Ajitgarh-Sh.Prem Singh Chandumajra (Anandpur Sahib) ----0 13 Tarn Taran-Sh. Ranjit Singh Brahmpura (Khadoor Sahib) ----0 Grand Total 00123 MPR 30-09-2020.xls ITEM 1.1 ITEM 1.1 A INSTALLMENTS DUE- 17TH LS MPs As on 30/09/2020 SN Nodal District 2019-20 (1st) 2019-20(2nd) Total 1 Amritsar-Sh. Gurjeet Singh Aujla 011 2 Bathinda-Smt.