Moncrieffe, Camille.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

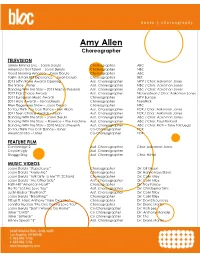

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Simple Life Thursdays Buck15

WWW.WIREWEEKLY.COM DISTRIBUTED EVERY THURSDAY IN MIAMI, THE BEACHES, AND FORT LAUDERDALE • THE LONGEST-RUNNING WEEKLY ON SOUTH BEACH LIKE US ON FACEBOOK VISIT WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/WIREMAGAZINE ISSUE #34 | 08/25/11 2 | wire magazine | follow wire on facebook & twitter: visit www.wireweekly.com & click on the icons FOR KINGS & QUEENS IT’S VODKA. FROM NEW ZEALAND. 42BELOW.COM ENJOY RESPONSIBLY. NEW ZEALANDERS AGREE: DRINK RESPONSIBLY. ©2010 42 BELOW AND THE 42 BOTTLE DESIGN ARE TRADEMARKS AND/OR REGISTERED TRADEMARKS. 42 BELOW IMPORTING COMPANY, CORAL GABLES, FL. VODKA – 40% ALC. BY VOL. -- 100% NEUTRAL SPIRITS DISTILLED FROM GRAIN. FLAVORED VODKAS - EACH 40% ALC. BY VOL. 34B_WIRED_King&Queen.indd | wire magazine | follow 1 wire on facebook & twitter: visit www.wireweekly.com & click on the icons 9/09/10 9:37 AM ALL WIRED UP BY THOMAS BARKER ELITE BEAT RELIVED! So I have to admit that one of my guilty town, Edison Farrow, to give Miami a new fabu party place pleasing crowd of yummy men, Jennie filled me in on how pleasures is taking the time to go back every Thursday night. excited she is to be hosting a new weekly gay event at her to my original nightlife columns to read hot little venue. about the crazy life I used to – and to Since the event takes place on a weeknight, everything gets a certain degree – still live in South started a bit early… which gives you plenty of time to get a Six years later, the party was still going strong, but unfortu- Florida. good buzz going and still get some much needed rest for the nately Buck15’s time at the Lincoln Lane space was up, leav- long Friday ahead. -

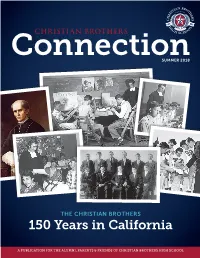

Connection – Summer 2018

ConnectionCHRISTIAN BROTHERS SUMMER 2018 THE CHRISTIAN BROTHERS 150 Years in California A PUBLICATION FOR THE ALUMNI, PARENTS & FRIENDS OF CHRISTIAN BROTHERS HIGH SCHOOL CB Leadership Team Lorcan P. Barnes President Chris Orr Principal June McBride Board of Trustees Director of Finance David Desmond ’94 The Board of Trustees at Christian Brothers High School is comprised of 11 volunteers Assistant Principal dedicated to safeguarding and advancing the school’s Lasallian Catholic college preparatory mission. Before joining the Board of Trustees, candidates undergo Michelle Williams training on Lasallian charism (history, spirituality and philosophy of education) and Assistant Principal Policy Governance, a model used by Lasallian schools throughout the District of Myra Makelim San Francisco New Orleans. In the 2017–18 school year, the board welcomed two new Human Resources Director members, Marianne Evashenk and Heidi Harrison. David Walrath serves in the role of chair and Mr. Stephen Mahaney ’69 is the vice chair. Kristen McCarthy Director of Admissions & The Policy Governance model comprises an inclusive, written set of goals for the school, Communications called Ends Policies, which guide the board in monitoring the performance of the school through the President/CEO. Ends Policies help ensure that Christian Brothers High Nancy Smith-Fagan School adheres to the vision of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the District Director of Advancement of San Francisco New Orleans. “The Board thanks the families who have entrusted their children to our school,” says Chair David Walrath. “We are constantly amazed by our unbelievable students. They are creative, hardworking and committed to the Lasallian Core Principles. Assisting Connection is a publication of these students are the school’s faculty, staff and administration. -

M I N U T E S Lane Regional Air Protection Agency Board of Directors Meeting Thursday January 9, 2019 1010 Main St, Springfield

M I N U T E S LANE REGIONAL AIR PROTECTION AGENCY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING THURSDAY JANUARY 9, 2019 1010 MAIN ST, SPRINGFIELD, OR 97477 ATTENDANCE: Board: Mike Fleck - Chair - Cottage Grove; Joe Pishioneri – Vice Chair – Springfield; Mysti Frost - Eugene; Betty Taylor – Eugene; Jeannine Parisi – Eugene; Joe Berney – Lane County; Gabrielle Guidero – Springfield Absent: Charlie Hanna – Eugene; Kathy Nichols – Oakridge Staff: Merlyn Hough–Director; Debby Wineinger; Nasser Mirhosseyni; Max Hueftle; Beth Erickson; Kelly Conlon Others: Jim Daniels – CAC Chair; Kathy Lamberg – CAC Member; Josh Proudfoot – Good Company OPENING: Fleck called the meeting to order at 12:18 p.m. 1. Call to Order 2. ADJUSTMENTS TO THE AGENDA: None 3. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION: Howard Saxion – Eugene: Mr. Saxion is a resident of Eugene, representing himself. For background he currently serves as an at-large member on City of Eugene’s Sustainability Commission. He is a retired environmental professional. He and Merlyn Hough were on the International Board of Directors for Air & Waste Management Association. He is not speaking on behalf of the commission. They also have public comments during their meetings and there has been a lot of increased interest on air quality issues by the public, especially on particulate matter and air toxics. The commission formed a committee and we are in the process of getting ourselves educated on local issues. We are an advisory committee to the City Council and City Manager. As an outcome, we may have some recommendations to present to the City Council that would be forwarded to LRAPA. Saxion is particularly concerned about LRAPA’s budget and he knows local government is always strapped for money. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

Copyright 2015 Marie T. Winkelmann

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository Copyright 2015 Marie T. Winkelmann DANGEROUS INTERCOURSE: RACE, GENDER AND INTERRACIAL RELATIONS IN THE AMERICAN COLONIAL PHILIPPINES, 1898 - 1946 BY MARIE T. WINKELMANN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Augusto F. Espiritu, Chair Professor Kristin Hoganson Professor Leslie J. Reagan Professor David Roediger, University of Kansas ABSTRACT “Intercourse with them will be dangerous,” warned the Deputy Surgeon General to all U.S. soldiers bound for the Philippines. In his 1899 pamphlet on sanitation, Colonel Henry Lippincott alerted troops to the consequences of becoming too friendly with the native population of the islands. From the beginning of the U.S. occupation of the Philippines, interracial sexual contact between Americans and Filipinos was a threatening prospect, informing everything from how social intercourse and diplomacy was structured, to how the built environment of Manila was organized. This project utilizes a transnational approach to examine a wide range of interracial sexual relationships -from the casual and economic to the formal and long term- between Americans and Filipinos in the overseas colony from1898–1946. My dissertation explores the ways that such relations impacted the U.S. imperial project in the islands, one that relied on a degree of social proximity with Filipinos on the one hand, while maintaining a hard line of racial and civilizational hierarchy on the other. -

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ AWARDS/NOMINATIONS MTV Hip Hop Video - Black Eyed Peas “My Humps” MTV Best New Artist in a Vide - Sean Paul “Get Busy” (Nominee) TELEVISION/FILM King Of The Dancehall (Creative Director) Dir. Nick Cannon American Girl: Saige Paints The Sky Dir. Vince Marcello/Martin Chase Prod. American Girl: Alberta Dir. Vince Marcello Sparkle (Co-Chor.) Dir. Salim Akil En Vogue: An En Vogue Christmas Dir. Brian K. Roberts/Lifetime Tonight SHow w Gwen Stefani (Co-Chor.) NBC The X Factor (Associate Chor.) FOX Cheetah Girls 3: One World (Co-Chor.) Dir. Paul Hoen/Disney Channel Make It Happen (Co-Chor.) Dir. Darren Grant New York Minute Dir. D. Gorgon American Music Awards w/ Fergie (Artistic Director) ABC/Dick Clark Productions Divas Celebrate Soul (Co-Chor.) VH1 So You Think You Can Dance Canada Season 1-4 CTV Teen Choice Awards w/ Will.I.Am FOX American Idol w/ Jordin Sparks FOX American Idol w/ Will.I.Am FOX Superbowl XLV Halftime Show w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX/NFL Soul Train Awards BET Idol Gives Back w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX Grammy Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) CBS / AEG Ehrlich Ventures NFL Thanksgiving Motown Tribute (Co-Chor.) CBS/NFL American Music Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Dick Clark Productions BET Hip Hop Awards (Co-Chor.) BET NFL Kickoff Concert w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) NFL Oprah w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Harpo Teen Choice Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Packaging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3th639mx Author Galloway, Catherine Suzanne Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge Professor Jack Citrin, Chair Professor Eric Schickler Professor Taeku Lee Professor Tom Goldstein Fall 2012 Abstract Packaging Politics by Catherine Suzanne Galloway Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jack Citrin, Chair The United States, with its early consumerist orientation, has a lengthy history of drawing on similar techniques to influence popular opinion about political issues and candidates as are used by businesses to market their wares to consumers. Packaging Politics looks at how the rise of consumer culture over the past 60 years has influenced presidential campaigning and political culture more broadly. Drawing on interviews with political consultants, political reporters, marketing experts and communications scholars, Packaging Politics explores the formal and informal ways that commercial marketing methods – specifically emotional and open source branding and micro and behavioral targeting – have migrated to the -

National Song Binder

SONG LIST BINDER ——————————————- REVISED MARCH 2014 SONG LIST BINDER TABLE OF CONTENTS Complete Music GS3 Spotlight Song Suggestions Show Enhancer Listing Icebreakers Problem Solving Troubleshooting Signature Show Example Song List by Title Song List by Artist For booking information and franchise locations, visit us online at www.cmusic.com Song List Updated March 2014 © 2014 Complete Music® All Rights Reserved Good Standard Song Suggestions The following is a list of Complete’s Good Standard Songs Suggestions. They are listed from the 2000’s back to the 1950’s, including polkas, waltzes and other styles. See the footer for reference to music speed and type. 2000 POP NINETIES ROCK NINETIES HIP-HOP / RAP FP Lady Marmalade FR Thunderstruck FX Baby Got Back FP Bootylicious FR More Human Than Human FX C'mon Ride It FP Oops! I Did It Again FR Paradise City FX Whoomp There It Is FP Who Let The Dogs Out FR Give It Away Now FX Rump Shaker FP Ride Wit Me FR New Age Girl FX Gettin' Jiggy Wit It MP Miss Independent FR Down FX Ice Ice Baby SP I Knew I Loved You FR Been Caught Stealin' FS Gonna Make You Sweat SP I Could Not Ask For More SR Bed Of Roses FX Fantastic Voyage SP Back At One SR I Don't Want To Miss A Thing FX Tootsie Roll SR November Rain FX U Can't Touch This SP Closing Time MX California Love 2000 ROCK SR Tears In Heaven MX Shoop FR Pretty Fly (For A White Guy) MX Let Me Clear My Throat FR All The Small Things MX Gangsta Paradise FR I'm A Believer NINETIES POP MX Rappers Delight MR Kryptonite FP Grease Mega Mix MX Whatta Man