Film Review: 'Robocop'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sebastian Jakub Konefał – Redaktor Prowadzący Numeru Grzegorz Fortuna Jr

FILM / NOWE MEDIA / SZTUKI WIZUALNE www.panoptikum.pl Adres do korespondencji: Mapowanie Północy Redakcja „Panoptikum” ul. Wita Stwosza 58/109 80-952 Gdańsk tel. (058) 523 24 50 [email protected] REDAKCJA: Mapping the North Grażyna Świętochowska – redaktor naczelna / [email protected] Sebastian Jakub Konefał – redaktor prowadzący numeru Grzegorz Fortuna Jr. – [email protected] Monika Bokiniec – [email protected] R ADA NAUKOWA: prof. Krzysztof Kornacki (Uniwersytet Gdański, Polska), prof. Ewa Mazierska (University of Lancashire, UK), prof. Mirosław Przylipiak (Uniwersytet Gdański, Polska), prof. Jerzy Szyłak (Uniwersytet Gdański, Polska), prof. Piotr Zwierzchowski (Uniwersytet Kazimierza Wielkiego, Polska) RECENZENCI: • Lyubov Bugayeva (Saint Petersburg University, Rosja) • Lucie Česálková (Masarykova Univerzita, Czechy) • Konrad Klejsa (Uniwersytet Łódzki, Polska) • Rafał Koschany (Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Polska) • Arkadiusz Lewicki (Uniwersytet Wrocławski, Polska) • Constantin Pârvulescu (Universitatea de Vest din Timisoara, Rumunia) • Tadeusz Szczepański, Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna im. Leona Schillera w Łodzi, Polska) • Balázs Varga (Eötvös Loránd University, Węgry) • Patrycja Włodek (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Krakowie, Polska) Redakcja językowa: Grzegorz Fortuna Jr., Martyna Skowron (język angielski) Projekt graficzny, okładka, layout i skład: Jacek Michałowski / Grupa 3M / [email protected] Promocja numeru: Tomasz Pupacz / [email protected] Materiały zdjęciowe udostępnione za zgodą właścicieli praw autorskich. Wydawca: Uniwersytet Gdański (http://cwf.ug.edu.pl/ojs/) Akademickie Centrum Kultury Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego „Alternator” Publikacja jest efektem badań akademickich przeprowadzonych w 2016 roku dzięki wsparciu udzielonemu z funduszy norweskich i funduszy EOG, pochodzących z Islandii, Liechtensteinu i Norwegii. This publication is the effect of the academic researches supported in 2016 by the Norway Grants and the EEA Grants with the financial contributions of Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. -

Half a Century with the Swedish Film Institute

Swedish #2 2013 • A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute Film 50Half a century with the Swedish Film Institute CDirector Lisah Langsethe exploresc identityk issuesi nin Hotel g in www.sfi.se scp reklambyrå Photo: Simon Bordier Repro: F&B Repro: Factory. Bordier Simon Photo: reklambyrå scp One million reasons to join us in Göteborg. DRAGON AWARD BEST NORDIC FILM OF ONE MILLION SEK IS ONE OF THE LARGEST FILM AWARD PRIZES IN THE WORLD. GÖTEBORG INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IS ALSO THE MAIN INDUSTRY WINDOW FOR NEW NORDIC FILM AND TALENT, FEATURING NORDIC FILM MARKET AND NORDIC FILM LAB. 1,000 SCREENINGS • 500 FILMS • 23 VENUES • 160,000 VISITS • WWW.GIFF.SE WELCOME Director, International Department Pia Lundberg Fifty and counting Phone +46 70 692 79 80 [email protected] 2013 marks the Swedish Film Institute’s various points in time. The films we support 50th anniversary. This gives us cause to look today are gradually added to history, giving back to 1963 and reflect on how society and that history a deeper understanding of the Festivals, features the world at large have changed since then. world we currently live in. Gunnar Almér Phone +46 70 640 46 56 Europe is in crisis, and in many quarters [email protected] arts funding is being cut to balance national IN THIS CONTEXT, international film festivals budgets. At the same time, film has a more have an important part to play. It is here that important role to play than ever before, we can learn both from and about each other. -

Waves Apart •Hollywood Q&A Page14

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 18, 2017 8:07:23 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of November 26 - December 2, 2017 Gustaf Skarsgård stars in “Vikings” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 Waves apart •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The sons of Ragnar are at war, putting the gains of their father into jeopardy as the unity of the Vikings is fractured. With Floki (Gustaf Skarsgård, “Kon-Tiki,” 2012) now letting the gods guide him, and Lagertha (Katheryn Winnick, “The Dark Tower,” 2017) dealing with civil unrest and a looming prophecy, it’s understandable why fans are anxious with anticipation for the season 5 premiere of “Vikings,” airing Wednesday, Nov. 29, on History Channel. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALES Motorsports& SERVICE IT’S MOLD ALLERGY SEASON 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Are you suffering from itchy eyes, sneezing, sinusitis We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC or asthma?Alleviate your mold allergies this season. Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Swedish Film Magazine #2 2010

Swedish Film #2 2010 • A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute P UMP UP THE NOISE Johannes Stjärne Nilsson and Ola Simonsson want the Sound of Noise to ring all over Cannes Bill Skarsgård Another shining son BATHING MICKY In Competition in Cannes A SILENT CHILD In Directors’ Fortnight ... BUT FILM IS MY MISTRESS Bergman revisited www.sfi.se “Brighton Rock” © 2010 Optimum Releasing “Centurion” © 2010 Celador Films / Pathe Productions “Antichrist” © 2009 Zentropa “Dear Alice” © 2009 One Tired Brother “Eden Lake” © 2008 Rollercoaster Films “The Descent: Part 2” © 2009 Celador Films / Pathe Productions “Arn - The Kingdom at Road’s End” © 2008 AB Svensk Filmindustri “Mammoth” © 2009 Memfis Film “The Cottage” © 2008 Steel Mill Yorkshire / UKFC “Hush” © 2009 Warp X / Fear Factory (Hush) SWEDEN’S BEST KEPT SECRET In less than four years Filmgate have supplied high end cost effective visual effects and DI solutions for over 30 feature films in 9 countries. Since the introduction of our 2k grading and conform services we have graded three feature films and several short films as well as TV commercials. In 2009, with the aid of regional funding, we have expanded our services into co-production. Looking forward to 2010 not only do we have exciting and challenging visual effects projects ahead, such as the eagerly anticipated UK features “Centurion” and “Brighton Rock”, we are also involved with a slate of US, UK and French projects as co-producers. www.filmivast.se www.filmgate.se CEO’S LETTER Director, International Department Pia Lundberg Phone +46 70 692 79 80 Unforgettable surprises [email protected] SOME THINGS JUST refuse to go away, no autumn, and Andreas Öhman with Simple matter how hard you try to shake them off. -

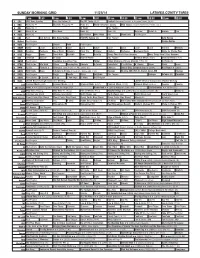

Sunday Morning Grid 11/23/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/23/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Houston Texans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) World/Adventure Sports MLS Soccer: Eastern Conference Finals, Leg 1 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Auto Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Pirates-Worlds 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Monkey 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Barbecue Heirloom Meals Home for Christy Rost 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (9:50) (N) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dhabi. -

Robocop Movie Review & Film Summary (2014) | Roger Ebert

In Memoriam 1942 – 2013 | ★ ★ ★ ★ ROGEREBERT.COM Choose a Section REVIEWS ROBOCOP ★ | Glenn Kenny February 11, 2014 | ☄ 83 Just to make it clear, in the event that my low rating for this movie gives you the immediate impression that I'm some kind of aggrieved fanboy, or hardcore Paul Verhoeven auteurist, or something: Cinematic sacrilege is the least of this "Robocop" remake's Print Page sins. No, the main thing wrong with "Robocop" is that it's dumb, and it's trashy, and it's both of those things in a not-good way, and Like 77 it tries to cover its dumb trashiness with a veneer of "exciting" visuals and production value, and also the fact that its producers 0 hired a group of very talented actors to inject some Very Talented Actor juice into their dumb trashy concoction. Tweet 27 The movie begins with what it believes constitutes some kind of wit: A television program of the near-future called "The Novak Element" in which a loud-mouth opinion-mongering host—is he right-wing? is he left-wing? the movie won't really make that clear (it's absolutely that kind of movie) but he is played by Samuel L. Jackson—expresses grievances over the fact that law-enforcement robots developed by "Omnicorp" are now being used in every country in the world but our own. To demonstrate how egregious this is, Novak shows his remote camera crew in what appears to be U.S. occupied Tehran, guarded by drones that keep it safe as suicide bombers run rampant in the streets. -

In 2028 Detroit, When Alex Action Fans in General 13-4

Sony Pictures Entertainment Pre-Planning Worksheet RoboCop - Brazil Release Date: February, 21th Synopsis: In 2028 Detroit, when Alex Murphy (Joel Kinnaman) - a loving husband, father and good cop - is critically injured in the line of duty, the multinational conglomerate OmniCorp sees their chance for a part-man, part-robot police officer. Marketing Positioning: Action fans in general 13-45, male skew under 30, Fans of Tropa de Elite and José Padilha Cast: Joel Kinnaman, Gary Oldman, Michael Keaton and Samuel L. Jackson Media Budget Support - Week 2 Support - Week 3 Planning 1 3 Flight Dates: Competitive: RELEASE DATES Media Strategy: Branding Campaign BR Showtimes Campaign Rich Media Sony Pictures Entertainment Pre-Planning Worksheet RoboCop - Brazil Release Date: February, 21th In 2028 Detroit, when Alex Murphy (Joel Kinnaman) - a loving husband, father and good cop - is critically injured in the line of duty, the multinational conglomerate OmniCorp sees their chance for a part-man, part-robot police officer. Action fans in general 13-45, male skew under 30, Fans of Tropa de Elite and José Padilha Joel Kinnaman, Gary Oldman, Michael Keaton and Samuel L. Jackson Theatrical Demos: Primary: Creative Dates RELEASE DATES Branding Campaign Objective: Media Tactic: Recommended Sites: Cinema com Rapadura Ingresso.com Rede Geek Twitter Melhores do Mundo Level Up! Adoro Cinema Click Jogos Showtimes Campaign Objective: Media Tactic: Recommended Sites: Takeover on the Ticket site ingresso.com Rich Media Sony Pictures Entertainment Pre-Planning Worksheet RoboCop - Brazil Release Date: February, 21th In 2028 Detroit, when Alex Murphy (Joel Kinnaman) - a loving husband, father and good cop - is critically injured in the line of duty, the multinational conglomerate OmniCorp sees their chance for a part-man, part-robot police officer. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Olivia Munn and Joel Kinnaman Call It Quits

Olivia Munn and Joel Kinnaman Call It Quits By Sanetra Richards Another couple, another breakup! Olivia Munn and Joel Kinnaman are now residents of Splitsville. According to UsMagazine.com, insider sources confirmed the split and said the two parted ways months ago. “They ended things a few months ago but both seem fine,” says a source. “A lot had to do with distance. He’s back filming in Toronto and she’s now in L.A. for good.” The Killing actor and Newsroom actress have remained friends through the breakup and are still very much fond of each other. While promoting the reboot of RoboCop, Kinnaman paid the Today Show a visit spoke well of Munn: “She’s a hoot, she’s a lot of fun.” Munn did the same in the May 2014 issue of Allure, saying, “If there was ever going to be a girl who would want her man to bring home a RoboCop suit, it would be me,” the 33-year-old gushed. “Joel is truly fantastic in it. How do you know when to call it quits on your relationship? Cupid’s Advice: Every so often things take a turn (possibly for the worst) in the relationship, and you are left asking yourself if you and your partner should just separate. Although the warning signs are typically loud and clear, you may be blinded by a few other things. Cupid has some ways to help you decide when it is time to call it quits: 1. Tension and arguments: Do not refuse to see the elephant in the room. -

Reservations for Two Love Is in the Air Cupids Delivery We L

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 RENT DUE WE LOVE OUR RESIDENTS! Roses are red, violets are blue, Four Season's is the place for you! We can't tell you how much we Your Community Team love having you live at our community. We want to express our appreciation by offering a Valentines day gift package which will include movie tickets and a restaurant gift card! 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jessica Burke LATE RENT Property Manager **Be the resident who submits the most unique Valentines Day card with a story on why you love $35.00 Georgeann Razor living at Four Season and Win the Valentines Day restaurant and movie package! Residents must Leasing Professional submit between February 1st thru 12th. ** Dane Wright SEE FLYER FOR MORE DETAILS! Maintenance Technician If Anything "Pops Up" Let Us Know! 9 10 11 12 13 14 Valentine's Day 15 Lee Montgomery 2nd LATE FEE Last Day to Turn Maintenance Technician Four Seasons has a tremendous maintenance staff that works hard everyday to make your home $25.00 In V- Day Cards to beautiful. If a maintenance issue "pops up" please let us know so Dane or Lee can take care of it Win $100 Office Hours as quickly as possible. Please do not let issues linger; they will be happy to fix them for you! Valentines Day Package! Monday Thru Friday Reservations for Two 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Don't for get about Valentines Day this year! Be sure to book your dinner reservations in advance Saturday 16 17 Presidents Day 18 19 20 21 22 so that you will not be dining in this Valentines Day. -

Contemporary Cyberpunk in Visual Culture: Identity and Mind/Body Dualism

Contemporary Cyberpunk in Visual Culture: Identity and Mind/Body Dualism 6/3/2019 Contemporary Cyberpunk in Visual Culture Identity and Mind/Body Dualism Benjamin, R. W. Jørgensen and Morten, G. Mortensen Steen Ledet Christensen Master’s Thesis Aalborg University Contemporary Cyberpunk in Visual Culture: Identity and Mind/Body Dualism Abstract In this world of increasing integration with technology, what does it mean to be human and to have your own identity? This paper aims to examine representations of the body and mind related to identity in contemporary cyberpunk. Using three examples of contemporary cyberpunk, Ghost in the Shell (2017), Blade Runner 2049 (2018), and Altered Carbon (2018), this paper focuses on identity in cyberpunk visual culture. The three entries are part of established cyberpunk franchises helped launch cyberpunk into the mainstream as a genre. The three works are important as they represent contemporary developments in cyberpunk and garnered mainstream attention in the West, though not necessarily due to critical acclaim. The paper uses previously established theory by Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway and expanding upon them into contemporary theory by Graham Murphy and Lars Schmeink, and Sherryl Vint. We make use of the terms posthumanism, transhumanism, dystopia, Cartesian mind/body dualism, embodiment, and disembodiment to analyse our works. These terms have been collected from a variety of sources including anthologies, books and compilations by established cyberpunk and science fiction theorists. A literary review compares and accounts for the terms and their use within the paper. The paper finds the same questions regarding identity and subjectivity in the three works as in older cyberpunk visual culture, but they differ in how they are answered.