History of the Alaskan Malamute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeshond Club of Nsw

KEESHOND CLUB OF NSW AN ILLUSTRATED EXTENDED BREED STANDARD Based upon the standard approved by the Australian National Kennel Council Keeshond Club of NSW 2003 KCNSW ILLUSTRATED EXTENDED BREED STANDARD INTRODUCTION YOUR NOTES PAGE ....................................................................................................................... The compilation of the Illustrated Extended Breed Standard of the Keeshond has been an on-going project of the Keeshond Club of New South Wales since ....................................................................................................................... 2001. The purpose of the extended standard is to provide a comprehensive explanation and illustration of the individual points of the Keeshond breed as ....................................................................................................................... defined in the written standard, as approved by the ANKC. ....................................................................................................................... It should be pointed out that the photographs used in this document have been donated from a range of sources, and are not meant to depict the ....................................................................................................................... —perfect dog“, rather, they are considered by breed specialists to be typical ....................................................................................................................... examples of the breed. ...................................................................................................................... -

H U Ndart Ik L Ar

H U NDART IK L A R NYHET Blinkfyren - Safety Blinker se sidan 44 N ETTOPRISLISTA FÖR ÅT ERFÖRSÄLJ A RE Dog Security AB AFFÄRSIDÉ FÖRSÄLJNINGSVILLKOR Att sälja marknadens bästa produkter så prisvärt som möjligt. För att Minimiorder 450:- exkl moms. uppnå detta arbetar vi enligt följande koncept: Kredit mot 10 dagar netto kan ges efter kreditprövning hos NCM Produkter: De bästa vi kan finna. Vissa produkter står utan Gerling. Dröjsmålsränta 24%, påminnelseavgift 45:-. Vid konkurrens! Finner vi bättre så byter vi. överskridna betalningsdagar dras krediten in. Endast en påminnelse Alla varor säljes styckevis: Tänk på att beställa styckevis. sänds ut före inkasso. Kunder som handlar mot efterkrav debiteras Rätt kunder: Vi säljer till specialhandeln. Vi säljer ej till varuhusen. fraktbolagets efterkravsavgift. K o n s u m e n t f ö rt ro e n d e: Genom produkter som Dressyrlänken har Fraktfritt från 1.995:- exklusive moms (Obs: Företagspaket1 kg konsumenterna fått stort förtroende för våra produkter. Konsumenter ko s t a r annars 127:00). Vid beställning av enbart T-Shirt tillkommer som börjat använda våra produkter brukar fortsätta och dessutom frakt endast 25:- exkl moms. Vi sänder postpaket med Företagspaket. berätta för sina vänner. Vi är själva aktiva med hund sedan många år, Returer godkännes ej utan att det är överenskommet med oss. vilket gör det lättare att finna bra produkter. Bra produkter ger ökat Returer skall ske på vårt fraktavtal och får inte beläggas med konsumentförtroende efterkrav. Anmärkningar ej gjorda inom 8 dagar efter varans mottagande godtages ej. R e s e r v a t i o n för tryckfel och prisförändringar som vi ej kan råda ö v e r, t ex på grund av den svenska kronkursen. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Joint Keeshond & Schipperke Club Breed Seminar/Assessment

Joint Keeshond & Schipperke Club Breed Seminar/Assessment Day TO BE HELD IN LINE WITH THE NEW JUDGES COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK Roade Village Hall, Roade, Northampton NN7 2LS rd Saturday 3 November 2018 The Keeshond & Schipperke Club are pleased to announce that they will be holding a Breed Appreciation Day held in line with the new Judges Competency Framework (JCF). The day is open to all. The day comprises of a breed talk aiming to provide or reinforce the basic knowledge required to establish a candidates/Level 1 Judge’s understanding and appreciation of the breed, in order to take a subsequent Multiple-Choice Breed Standard eXam (dependant on eligibility – see below). Attending the Breed Appreciation Day and passing the Multiple-choice Breed Standard Exam forms part of the criteria that will enable the candidate to attain Level 2 status when the JCF goes live. Subjects covered in the morning session will include a brief history of the Keeshond breed, function of the breed and its correlation to its confirmation and movement and elaboration on breed specifics to other Spitz breeds. All elements of the standard will be covered, and there will be live eXhibits. The exam will be before lunch. The Schipperke will be covered in the afternoon with the eXam. Candidates can do both the morning and afternoon sessions, providing they meet the criteria below. Multiple-Choice EXam Eligibility – in order to sit this eXam, candidates must either already be approved to award CC’s to a breed or will have to have fulfilled all the entry level criteria (if not approved to award CC’s) which includes the following: 1) Attend KC Requirements of a Dog Show Judge seminar and eXam pass. -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

Non-Sporting Group Breed Standards

Non-Sporting Group Breed Standards Amended July 29, 2020 Group 6: Non-Sporting (20) Breed Effective Date Page Disqualifications for the Non-Sporting Group 3 American Eskimo Dogs November 30, 1994 5 Bichons Frises November 30, 1988 7 Boston Terriers March 30, 2011 9 Bulldogs August 31, 2016 12 Chinese Shar-Pei February 28, 1998 16 Chow Chows July 29, 2020 18 Coton de Tulear October 1, 2013 21 Dalmatians September 6, 1989 25 Finnish Spitz October 3, 2018 28 French Bulldogs June 5, 2018 30 Keeshonden January 1, 1990 32 Lhasa Apsos October 1, 2019 34 Lowchen July 28, 2010 36 Norwegian Lundehunds July 1, 2008 38 Poodles (Miniature/Standard) March 27, 1990 40 Schipperkes January 1, 1991 43 Shiba Inu March 31, 1997 45 Tibetan Spaniels July 28, 2010 48 Tibetan Terriers March 10, 1987 50 Xoloitzcuintli January 1, 2009 52 Disqualifications: Non-Sporting Breeds American Eskimo Dogs Any color other than white or biscuit cream. Blue eyes. Height: under 9" or over 19". Boston Terriers Eyes blue in color or any trace of blue. Dudley nose. Docked tail. Solid black, solid brindle, or solid seal without required white markings. Any color not described in the standard. Bulldogs Blue or green eye(s) or parti-colored eye(s). Brown or liver-colored nose. Colors or markings not defined in the standard. The merle pattern. Chinese Shar-Pei Pricked ears. Solid pink tongue. Absence of a complete tail. Albino; not a solid color, i.e.: brindle; parti-colored; spotted; patterned in any combination of colors. Chow Chows Drop ear or ears. -

Non-Sporting Dogs

GROUP VI NON-SPORTING DOGS n American Eskimo Dog (Miniature & Standard) n Bichon Frise n Boston Terrier n Bulldog n Chinese Shar-Pei n Chow Chow n Dalmatian n French Bulldog n German Pinscher n Japanese Spitz n Keeshond n Lhasa Apso n Lowchen n Poodle (Miniature & Standard) n Schipperke n Shiba Inu n Shih Tzu n Tibetan Spaniel n Tibetan Terrier n Xoloitzcuintli (Miniature & Standard) Listed Breeds n Akita (Japanese) 306-06-05 Canadian Kennel Club Official Breed Standards GROUP VI NON-SPORTING DOGS VI-1 American Eskimo Dog (Miniature & Standard) General Appearance The American Eskimo Dog, a loving companion dog, presents a picture of strength and agility, alertness and beauty. It is a small to medium- size Nordic type dog, always white, or white with biscuit cream. The American Eskimo Dog is compactly built and well balanced, with good substance, and an alert smooth gait. The face is Nordic type with erect triangular shaped ears and distinctive black points (lips. nose. and eye rims). The white double coat consists of a short, dense undercoat, with a longer guard hair growing through it forming the outer coat, which is straight with no curl or wave. The coat is thicker and longer around the neck and chest forming a lion-like ruff, which is more noticeable on dogs than on bitches. The rump and hind legs down to the hocks are also covered with thicker, longer hair forming the characteristic breeches. The richly plumed tail is carried loosely on the back. Temperament The American Eskimo Dog is intelligent, alert, and friendly, although slightly conservative. -

Fleyer Englisch

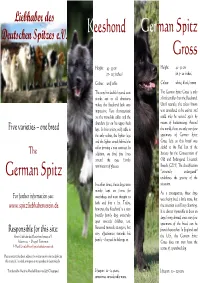

Liebhaber des Deutschen Spitzes e.V. Keeshond Ger man Spitz Gross Height: 43 - 55 cm Height: 42 - 50 cm …………. (17 - 21.5 inches) ……………... (16.5 - 20 inches) Colour: wolf sable Colour: white, black, brown The way his double-layered coat The German Spitz Gross is only stands out in all directions a little smaller than the Keeshond. makes the Keeshond look very Until recently, the colour brown impressive. Very characteristic was considered to be extinct and are the mane-like collar and the could only be revived again by abundant fur on his upper back means of backcrossing. Around Five varieties – one breed legs. In this variety, wolf sable is the world, there are only very few the only colour, the lighter legs specimens of German Spitz and the lighter streak behind the Gross left, so this breed was collar forming a nice contrast. In added to the Red List of the The addition, we find fine lines Society for the Conservation of around the eyes faintly Old and Endangered Livestock reminiscent of glasses. Breeds (GEH). The classification German Spitz “extremely endangered” underlines the gravity of the In earlier times, these dogs were situation. mainly kept on farms for As a consequence, these dogs For further information see: watchdogs and were thought to were being bred a little more, but www.spitzliebhaberverein.de bark and bite a lot. Today, the situation is still very alarming. however, the Keeshond is a very It is almost impossible to draw on friendly family dog, extremely dogs living abroad, since very few open towards children, too. -

The Keeshond…A Smiling Touch of Dutch by Origin, It Is a Member Of

The Keeshond…A Smiling Touch of Dutch By origin, it is a member of the spitz family of dogs and is related to the Norwegian Elkhound, The Chow Chow, the Finnish Spitz and the Pomeranian. The Spitz breed is characterized by a long, dense coat, erect, pointed ears and a tail that curls over the back. The Keeshond takes its name from "Kees" a dog owned by Cornelius de Gyzelaar (Kees was the nickname for Cornelius). Gyzelaar was the leader of the Patriot Party in politically torn, 18th century Holland. Because Kees was Gyzelaar’s constant companion, the dog became the symbol of the Patriot Party. The Pug was the official dog of the ruling opposition - the House of Orange. This decree occurred in 1572 after one saved the live of Prince William at the battle for Hermingny. The Pug woke up the sleeping prince by barking just before the enemy attacked. After the House of Orange successfully quelled a revolt by the Patriot Party, most Dutch no longer were eager to be associated with the rebellion of the defeated Patriot Party. Fearing for their own well-being, they abandoned their Keeshonden. A few farmers and barge captains kept their dogs. Unfortunately , the breed’s safe haven aboard the barges was short lived. With the development of larger vessels, larger breeds could be accommodated aboard them. Thus the Keeshond population further declined to the point of near extinction by the early 19th century. The Keeshond finally enjoyed a revival in popularity in the 1920’s at English shows were bred by J.D. -

Breed Categorisations

Breed Categorisations SMALL (UNDER 10KG) Affenpinscher American Hairless Terrier Australian Silky Terrier Australian Terrier Bedlington Terrier Bichon Frise Bolognese Border Terrier Boston Terrier Brussels Griffon (Griffon Bruxellois) Bulldog (Toy) Cairn Terrier Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Cesky Terrier Chihuahua (Long Haired) Chihuahua (Short Haired) Chinese Crested Coton De Tulear Dachshund (Miniature Long-Haired) Dachshund (Miniature Smooth/Short-Haired) Dachshund (Miniature Wire-Haired) Dandie Dinmont Terrier English Toy Terrier (Black & Tan) Fox Terrier (Smooth) Fox Terrier (Wire) French Bulldog Havanese Italian Greyhound Jack Russell Terrier Japanese Chin King Charles Spaniel Lakeland Terrier Lancashire Heeler Lhasa Apso Lowchen (Little Lion Dog) Maltese Manchester Terrier Mexican Hairless Miniature Pinscher Miniature Schnauzer Norfolk Terrier Norwegian Lundehund Norwich Terrier Papillon Parson Russell Terrier Patterdale Terrier Pekinese Pomeranian Poodle (Miniature) Poodle (Toy) Portuguese Podengo Pequeno (Smooth) Portuguese Podengo Pequeno (Wire) Pug Prague Ratter Ratonero Bodeguero Andaluz Schipperke Scottish Terrier Sealyham Terrier Shetland Sheepdog Shih Tzu Skye Terrier Sporting Lucas Terrier Tibetan Spaniel West Highland White Terrier Yorkshire Terrier MEDIUM (10 KG - 20 KG) Alaskan Klee Kai Alpine Dachsbracke American Cocker Spaniel American Water Spaniel Australian Cattle Dog Australian Kelpie Australian Shepherd Basenji Basset Bleu De Gascogne Basset Fauve De Bretagne Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) Basset Griffon Vendeen -

Aversives for Dogs

DOG BREEDS: NORDIC OF ALL THE FAMILIES OF DOGS, the northern bred canines are arguably man’s most reliable best friend. For centuries, these bold, hardy and intelligent dogs have lived and worked closely with humans performing a variety of services, from guarding to sledding to hunting. But, in addition to these critical jobs, they have also remained our eager and affectionate companions. Also known as the Nordic or Spitz dogs, these beautiful and complex canines are found in several different dog groups, from the well- known Siberian Husky in the Working Group to the pampered Pomeranian in the Toy Group. They include, but are not limited to: the Akita, the Alaskan Malamute, the American Eskimo Dog, the Chow Chow, the Finnish Spitz, the Keeshond, the Norwegian Elkhound, the Pomeranian, the Samoyed, the Schipperke, the Shiba Inu and the Siberian Husky. Despite differences in size and color, most Nordic breeds share several common Norwegian Elkhound characteristics . Some Like It . Cold? Though bred for a variety of different jobs, most northern dogs are, by necessity, physically built to handle the cold weather from which they originate. • Double Coat: Spitzes come from a region with such extreme cold temperatures that nature has outfitted them with TWO coats. A short undercoat that is almost Alaskan Malamute akin to “down” provides insulation for warmth. On top of the undercoat is a layer of guard hairs that are twice as long and water-resistant. Twice the fur definitely means twice the grooming! Be sure to brush and, when necessary, trim your Nordic dog’s coat regularly to prevent painful matting. -

Border Collie

SCRAPS Breed Profile AMERICAN ESKIMO DOG Stats Country of Origin: Nordic Region Group: Non-Sporting Group Use today: Primarily companion dogs today and participate in conformation, obedience and agility competitions.. Life Span: 15+ years Color: The profuse coat is always white, or white with biscuit or cream markings. Its skin is pink or gray. Black is the preferred color of its eyelids, gums, nose and pads. Coat: The coat is heavy around the neck, creating a ruff or mane, especially in males. The coat of the American Eskimo should not curl or wave; the undercoat should be thick and plush with the harsher outer coat growing up through it. Grooming: The thick, snowy white coat is easy to groom. Brush with a firm bristle brush twice a week. It should be brushed daily when it is shedding. This breed is an average shedder. Height: Toy: 9 - 12 inches; Miniature: over 12 up to 15 inches; Standard: over 15 up to 19 inches Weight: Toy: 6 - 10 pounds; Miniature: 10 - 20 pounds; Standard 18 - 35 pounds Profile In Brief: Intelligent, alert and friendly, the males. The breed is slightly longer than it is tall. American Eskimo Dog is also an excellent The coat of the American Eskimo should not curl watchdog, protective of his home and family. or wave; the undercoat should be thick and The Eskie learns quickly and is eager to please plush with the harsher outer coat growing up his owner, but requires daily exercise. Their through it. No colors other than those described voluminous coat sheds and needs to be brushed above are allowed.