A Policy Study of the Emergence of a Joint Interdisciplinary School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odd Foot (1934)

TesioPower jadehorse Odd Foot (1934) Voltigeur 2 Vedette Mrs Ridgeway 19 GALOPIN The Flying Dutchman 3 Flying Duchess Merope 3 St Simon (1881) Harkaway 2 King Tom POCAHONTAS 3 St Angela Ion 4 Adeline Little Fairy 11 St Serf (1887) Pantaloon 17 Windhound Phryne 3 Thormanby Muley Moloch 9 Alice Hawthorn Rebecca 4 Feronia (1868) The Baron 24 STOCKWELL POCAHONTAS 3 Woodbine TOUCHSTONE 14 Honeysuckle Beeswing 8 Sain (1894) Melbourne 1 West Australian Mowerina 7 Solon BIRDCATCHER 11 BIRDCATCHER MARE Hetman Platoff Mare 23 Barcaldine (1878) STOCKWELL 3 Belladrum Catherine Hayes 22 Ballyroe Adventurer 12 Bon Accord BIRDCATCHER MARE 23 The Task (1889) Voltigeur 2 Vedette Mrs Ridgeway 19 GALOPIN The Flying Dutchman 3 Flying Duchess Merope 3 Satchel (1882) Longbow 21 Toxophilite Legerdemain 3 Quiver Y Melbourne 25 Y Melbourne Mare Brown Bess 3 Harry Shaw (1911) GLENCOE 1 VANDAL (RH) Tranby Mare (RH) Virgil (rh) Yorkshire 2 Hymenia (RH) Little Peggy (RH) Hindoo (1878) Boston (RH) LEXINGTON (RH) Alice Carneal (RH) Florence Weatherbit 12 Weatherwitch II Birdcatcher Mare (24) 24 HANOVER (1884) Don John 2 Iago Scandal 11 BONNIE SCOTLAND Gladiator 22 Queen Mary Plenipotentiary Mare 10 BOURBON BELLE (1869) GLENCOE 1 VANDAL (RH) Tranby Mare (RH) Ella D (RH) Woodpecker (RH) Falcon (RH) Ophelia (RH) Hand Bell () Sir Hercules 2 BIRDCATCHER Guiccioli 11 The Baron Economist 36 Echidna Miss Pratt 24 STOCKWELL (1849) Sultan 8 GLENCOE Trampoline 1 POCAHONTAS Muley 6 Marpessa Clare 3 Miss Bell (1868) Whalebone 1 Camel Selim Mare (24) 24 TOUCHSTONE Master Henry 3 -

Animal Painters of England from the Year 1650

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

Mumtaz Mahal (1921)

TesioPower jadehorse Mumtaz Mahal (1921) Windhound 3 THORMANBY Alice Hawthorn 4 Atlantic Wild Dayrell 7 Hurricane Midia 3 Le Sancy (1884) NEWMINSTER 8 Strathconan Souvenir 11 Gem Of Gems Y Melbourne 25 Poinsettia LADY HAWTHORN 4 Le Samaritain (1895) THE BARON 24 STOCKWELL POCAHONTAS 3 DONCASTER Teddington 2 Marigold Ratan Mare 5 Clementina (1880) Touchstone 14 NEWMINSTER Beeswing 8 CLEMENCE Euclid 7 Eulogy Martha Lynn 2 Roi Herode (1904) VEDETTE 19 Galopin Flying Duchess 3 Galliard MACARONI 14 Mavis Beau Merle 13 War Dance (1887) STOCKWELL 3 Uncas Nightingale 1 War Paint Buccaneer 14 Piracy Newminster Mare 1 Roxelane (1894) VOLTIGEUR 2 VEDETTE Mrs Ridgeway 19 SPECULUM ORLANDO 13 Doralice Preserve 1 Rose Of York (1880) Windhound 3 THORMANBY Alice Hawthorn 4 Rouge Rose Redshank 15 Ellen Horne Delhi 1 The Tetrarch (1911) THE BARON 24 STOCKWELL POCAHONTAS 3 DONCASTER Teddington 2 Marigold Ratan Mare 5 Tadcaster (1877) Touchstone 14 NEWMINSTER Beeswing 8 CLEMENCE Euclid 7 Eulogy Martha Lynn 2 Bona Vista (1889) Gladiator 22 Sweetmeat Lollypop 21 MACARONI Pantaloon 17 Jocose Banter 14 Vista (1879) Harkaway 2 KING TOM POCAHONTAS 3 Verdure NEWMINSTER 8 May Bloom LADY HAWTHORN 4 Vahren (1897) VOLTIGEUR 2 VEDETTE Mrs Ridgeway 19 SPECULUM ORLANDO 13 Doralice Preserve 1 Hagioscope (1878) Sweetmeat 21 MACARONI Jocose 14 Sophia STOCKWELL 3 Zelle Babette 23 Castania (1889) Harkaway 2 KING TOM POCAHONTAS 3 Kingcraft VOLTIGEUR 2 Woodcraft Venison Mare 11 Rose Garden (1878) NEWMINSTER 8 HERMIT Seclusion 5 Eglentyne Parmesan 7 Mabille Rigolboche 2 VOLTIGEUR -

'Choctaw: a Cultural Awakening' Book Launch Held Over 18 Years Old?

Durant Appreciation Cultural trash dinner for meetings in clean up James Frazier Amarillo and Albuquerque Page 5 Page 6 Page 20 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma May 2013 Issue Tribal Council meets in regular April session Choctaw Days The Choctaw Nation Tribal Council met in regular session on April 13 at Tvshka Homma. Council members voted to: • Approve Tribal Transporta- returning to tion Program Agreement with U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs • Approve application for Transitional Housing Assis- tance Smithsonian • Approve application for the By LISA REED Agenda Support for Expectant and Par- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma 10:30 a.m. enting Teens, Women, Fathers Princesses – The Lord’s Prayer in sign language and their Families Choctaw Days is returning to the Smithsonian’s Choctaw Social Dancing • Approve application for the National Museum of the American Indian in Flutist Presley Byington Washington, D.C., for its third straight year. The Historian Olin Williams – Stickball Social and Economic Develop- Dr. Ian Thompson – History of Choctaw Food ment Strategies Grant event, scheduled for June 21-22, will provide a 1 p.m. • Approve funds and budget Choctaw Nation cultural experience for thou- Princesses – Four Directions Ceremony for assets for Independence sands of visitors. Choctaw Social Dancing “We find Choctaw Days to be just as rewarding Flutist Presley Byington Grant Program (CAB2) Soloist Brad Joe • Approve business lease for us as the people who come to the museum say Storyteller Tim Tingle G09-1778 with Vangard Wire- it is for them,” said Chief Gregory E. -

John Ferneley Catalogue of Paintings

JOHN FERNELEY (1782 – 1860) CATALOGUE OF PAINTINGS CHRONOLOGICALLY BY SUBJECT Compiled by R. Fountain Updated December 2014 1 SUBJECT INDEX Page A - Country Life; Fairs; Rural Sports, Transport and Genre. 7 - 11 D - Dogs; excluding hounds hunting. 12 - 23 E - Horses at Liberty. 24 - 58 G - Horses with grooms and attendants (excluding stabled horses). 59 - 64 H - Portraits of Gentlemen and Lady Riders. 65 - 77 J - Stabled Horses. 74 - 77 M - Military Subjects. 79 P - Hunting; Hunts and Hounds. 80 - 90 S - Shooting. 91 - 93 T - Portraits of Racehorses, Jockeys, Trainers and Races. 94 - 99 U - Portraits of Individuals and Families (Excluding equestrian and sporting). 100 - 104 Index of Clients 105 - 140 2 NOTES ON INDEX The basis of the index are John Ferneley’s three account books transcribed by Guy Paget and published in the latter’s book The Melton Mowbray of John Ferneley, 1931. There are some caveats; Ferneley’s writing was always difficult to read, the accounts do not start until 1808, are incomplete for his Irish visits 1809-1812 and pages are missing for entries in the years 1820-1826. There are also a significant number of works undoubtedly by John Ferneley senior that are not listed (about 15-20%) these include paintings that were not commissioned or sold, those painted for friends and family and copies. A further problem arises with unlisted paintings which are not signed in full ie J. Ferneley/Melton Mowbray/xxxx or J. Ferneley/pinxt/xxxx but only with initials, J. Ferneley/xxxx, or not at all. These paintings may be by John Ferneley junior or Claude Loraine Ferneley whose work when at its best is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from that of their father or may be by either son with the help of their father. -

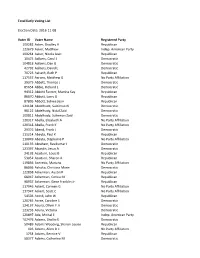

Total Early Voting List Election Date

Total Early Voting List Election Date: 2016-11-08 Voter ID Voter Name Registered Party 109282 Aaker, Bradley H Republican 123679 Aaker, Matthew Indep. American Party 109264 Aaker, Nicola Jean Republican 10475 Aalbers, Carol J Democratic 104818 Aalbers, Dan G Democratic 42792 Aalbers, David L Democratic 70723 Aalseth, Ruth P Republican 117557 Aarons, Matthew G No Party Affiliation 29375 Abbett, Thomas J Democratic 85654 Abbie, Richard L Democratic 94312 Abbott Farmer, Marsha Kay Republican 86670 Abbott, Larry G Republican 87805 Abbott, Sidnee Jean Republican 121104 Abdelhade, Suleiman N Democratic 98122 Abdelhady, Nidal Zaid Democratic 100811 Abdelhady, Sulieman Zaid Democratic 120317 Abella, Elizabeth A No Party Affiliation 120318 Abella, Frank K No Party Affiliation 29376 Abend, Frank J Democratic 111214 Abeyta, Paul K Republican 110049 Abeyta, Stephanie P No Party Affiliation 110135 Abraham, Ravikumar I Democratic 123397 Abundis, Jesus A Democratic 24192 Acaiturri, Louis B Republican 53052 Acaiturri, Sharon A Republican 119856 Acevedo, Mariana No Party Affiliation 86036 Achoka, Christina Marie Democratic 122858 Ackerman, Austin R Republican 68947 Ackerman, Corina M Republican 98937 Ackerman, Gene Franklin Jr Republican 117946 Ackert, Carmen G No Party Affiliation 117947 Ackert, Scott C No Party Affiliation 54503 Acord, John W Republican 120765 Acree, Caroline S Democratic 124137 Acuna, Oliver F Jr Democratic 123233 Acuna, Victoria Democratic 120897 Ada, Michal E Indep. American Party 102476 Adamo, Shellie E Democratic 50489 Adams Wooding, Sharon Louise Republican 426 Adams, Allen D Ii No Party Affiliation 1754 Adams, Bernice V Republican 58377 Adams, Catherine M Democratic 28234 Adams, Cheryl A Republican 28235 Adams, David L Republican 427 Adams, Irma M Indep. -

Obituary "O" Index

Obituary "O" Index Copyright © 2004 - 2021 GRHS DISCLAIMER: GRHS cannot guarantee that should you purchase a copy of what you would expect to be an obituary from its obituary collection that you will receive an obituary per se. The obituary collection consists of such items as a) personal cards of information shared with GRHS by researchers, b) www.findagrave.com extractions, c) funeral home cards, d) newspaper death notices, and e) obituaries extracted from newspapers and other publications as well as funeral home web sites. Some obituaries are translations of obituaries published in German publications, although generally GRHS has copies of the German versions. These German versions would have to be ordered separately for they are kept in a separate file in the GRHS library. The list of names and dates contained herein is an alphabetical listing [by surname and given name] of the obituaries held at the Society's headquarters for the letter combination indicated. Each name is followed by the birth date in the first column and death date in the second. Dates may be extrapolated or provided from another source. Important note about UMLAUTS: Surnames in this index have been entered by our volunteers exactly as they appear in each obituary but the use of characters with umlauts in obits has been found to be inconsistant. For example the surname Büchele may be entered as Buchele or Bahmüller as Bahmueller. This is important because surnames with umlauted characters are placed in alphabetic order after regular characters so if you are just scrolling down this sorted list you may find the surname you are looking for in an unexpected place (i.e. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

2009 International List of Protected Names

Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities __________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] 2 03/02/2009 International List of Protected Names Internet : www.IFHAonline.org 3 03/02/2009 Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, -

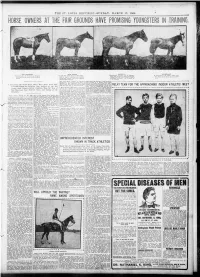

HORSE OWN Tttitb

rf , - . THE ST. LOUIS REPUBLIC: SUNDAY. MARCH 13, 1904. HORSE OWN RS AT THE FAIR GROUNDS HAVE PROMISING YOUNGSTERS IN .TRAINING . Vft . ft f LAUNCELOT. JACK TOUNG. LAUREL L. JOE KELLEY. SIR chestnut colt by Cayuga oar-ol- A In the Baker stable, who Four-- v d In S W Street'-- string at The old war horse of the Baker string. Jollv Nun. entered in stakes at Klnloch, the Fair Grounds, ready lor his morning Jack Is now a and looking Delmar and the Tair Grounds and a , has shown speed in his morning work- gallop. strong and healthy. His owner expects promising performer. lie Is owned by outs. much of him this jear. C 11. Law son. ful, dam Helen Thomis, by Hanover: been entered In this race. It was expected brown filly, b Fliudtt, dain Belle of that Captain S S. Brown would have Homdel. by His Highness. The great four in the Derby, but he has only nom- C. M. Lnwwin and Colonel Ilugh Baker Some Good Two-Yea- r mares. Imp Ida Pickwick ind Cleophus. inated Auditor and Proceeds, two of tho RELAY TEAM FOR THE APPROACHING INDOOR ATHLETIC MEET IIae will also soon foal at this noted farm. best colts thit were raced at Chicago last Now Stabled the Old year. John A. Drake' has entered Ort Olds Among the Juveniles at M. b Since the time of Sir Walter, a turf stat- Wells and Jocund. II. Zlegler will It 9 t ll Htl It H' t Courfae Young in Better Condition Than lie Was at represented by Don John and Wayfarer. -

CHAPTERS from TURF HISTORY "By U^EWMARKET 2-7

CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY "By U^EWMARKET 2-7 JOHNA.SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 540 286 Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University 200 Westboro Road North Grafton. MA 01535 CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY The Two CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY BY NEWMARKET LONDON "THE NATIONAL REVIEW" OFFICE 43 DUKE STREET, ST. JAMES'S. S.W.I 1922 '"^1"- 6 5f \^n The author desires to make due acknowledgment to Mr. Maxse, Editor of the National Review, for permission to reprint the chapters of this book which first appeared under his auspices. CONTENTS PAGK I. PRIME MINISTERS AND THEIR RACE-HORSES II II. A GREAT MATCH (VOLTIGEUR AND THE FLYING DUTCHMAN) . -44 III. DANEBURY AND LORD GEORGE BENTINCK . 6l IV. THE RING, THE TURF, AND PARLIAMENT (MR. GULLY, M.P.) . .86 V. DISRAELI AND THE RACE-COURSE . IO3 VI. THE FRAUD OF A DERBY .... I26 VII. THE TURF AND SOME REFLECTIONS . I44 ILLUSTRATIONS THE 4TH DUKE OF GRAFTON .... Frontispiece TO FACE PAGE THE 3RD DUKE OF GRAFTON, FROM AN OLD PRINT . 22 THE DEFEAT OF CANEZOU IN THE ST. LEGER ... 35 BLUE BONNET, WINNER OF THE ST. LEGER, 1842 . 45 THE FLYING DUTCHMAN, WINNER OF THE DERBY AND THE ST. LEGER, 1849 .48 VOLTIGEUR, WINNER OF THE DERBY AND THE ST. LEGER, 1850 50 THE DONCASTER CUP, 1850. VOLTIGEUR BEATING THE FLYING DUTCHMAN 54 trainer's COTTAGE AT DANEBURY IN THE TIME OF OLD JOHN DAY 62 THE STOCKBRIDGE STANDS 62 LORD GEORGE BENTINCK, AFTER THE DRAWING BY COUNT d'orsay 64 TRAINER WITH HORSES ON STOCKBRIDGE RACE-COURSE .