Headaches in Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronic Use of Opioid Medications Before and After Bariatric Surgery

Supplementary Online Content Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, et al. Chronic use of opioid medications before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278344 eFigure. Opioid Dispensings in 60 Days Before and 60 Days After Bariatric Surgery eTable 1. Opioid Classification and Morphine Equivalents Conversion Factors for Opioids Administered by Tablet, Capsule, Liquid, Transdermal Patch, and Transmucosal Formulations eTable 2. ICD-9 Codes for Comorbid Diagnosis of Substance Abuse, Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and/or Depression eTable 3. ICD-9 Codes for Inclusion and Exclusion of Chronic Pain Diagnoses eTable 4. Therapeutic Classes, Generic Names, and Selected Brand Names of Covariate Medications eTable 5. Types of Opioids Dispensed During the Year Before and the Year After Bariatric Surgery Among Presurgery Chronic Opioid Users eTable 6. Types of Opioids Used Before and After Bariatric Surgery Among 933 Individuals With Chronic Opioid Use Before Bariatric Surgery eTable 7. Unadjusted Characteristics of Chronic Opioid Users According to Whether or Not Both Presurgery and Postsurgery Body Mass Indexes (BMIs) Data Were Available eTable 8. Presurgery and Postsurgery Use of Opioids and Selected Other Analgesic and Adjunctive Pain Medication Classes Among Presurgery Chronic Opioid Users With Presurgery Chronic Pain Diagnoses This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: -

Menstrually Related and Nonmenstrual Migraines in A

MENSTRUALLY RELATED AND NONMENSTRUAL MIGRAINES IN A FREQUENT MIGRAINE POPULATION: FEATURES, CORRELATES, AND ACUTE TREATMENT DIFFERENCES A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brenda F. Pinkerman March 2006 This dissertation entitled MENSTRUALLY RELATED AND NONMENSTRUAL MIGRAINES IN A FREQUENT MIGRAINE POPULATION: FEATURES, CORRELATES, AND ACUTE TREATMENT DIFFERENCES by BRENDA F. PINKERMAN has been approved for the Department of Psychology and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kenneth A. Holroyd Distinguished Professor of Psychology Benjamin M. Ogles Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences PINKERMAN, BRENDA F. Ph.D. March 2006. Clinical Psychology Menstrually Related and Nonmenstrual Migraines in a Frequent Migraine Population: Features, Correlates, and Acute Treatment Differences (307 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Kenneth A. Holroyd This research describes and compares menstrually related migraines as defined by recent proposed guidelines of the International Headache Society (IHS, 2004) to nonmenstrual migraines in a population of female migraineurs with frequent, disabling migraines. Migraines are compared by frequency per day of the menstrual cycle, headache features, use of abortive and rescue medications, and acute migraine treatment outcomes. In addition, this study explores predictors of acute treatment response and headache recurrence within 24 hours following acute migraine treatment for menstrually related migraines. Participants are 107 menstruating female migaineurs who met IHS (2004) proposed criteria for menstrually related migraines and completed headache diaries using hand-held computers. Diary data are analyzed using repeated measures logistic regression. The frequency of migraines is significantly increased during the perimenstrual period, and menstrually related migraines are of longer duration and greater frequency with longer lasting disability than nonmenstrual migraines. -

BUTALBITAL ANALGESICS Allzital (Butalbital-Acetaminophen

BUTALBITAL ANALGESICS Allzital (butalbital-acetaminophen), butalbital-aspirin-caffeine, butalbital-aspirin-caffeine- codeine, butalbital-acetaminophen, butalbital-acetaminophen-caffeine, butalbital- acetaminophen-caffeine-codeine, Vanatol LQ (butalbital-acetaminophen-caffeine liquid oral solution) RATIONALE FOR INCLUSION IN PA PROGRAM Background Butalbital containing products are non-opioid analgesics that contain a combination of different drug products indicated for the relief of the symptom complex of tension (or muscle contraction) headache pain. Butalbital is a short to intermediate-acting barbiturate that works in concert with acetaminophen, an antipyretic non-salicylate agent, aspirin, a pain-relieving NSAID, and caffeine, a stimulant that works in the CNS, to decrease pain via a mechanism that isn’t well understood. Butalbital is a habit-forming drug that potentiates the effects of other commonly abuse drugs or substances like alcohol. Caffeine might help increase vasodilation and smooth muscle relaxation, while butalbital is thought to help balance the CNS stimulation caused by caffeine and produces depressant effects (1). Regulatory Status FDA approved indication: Butalbital containing products are used in the relief of the symptom complex of tension or muscle contraction headaches (2-8). Frequent use of acute medications is generally thought to cause medication-overuse headache. To decrease the risk of medication-overuse headache (“rebound headache” or “drug-induced headache”) many experts limit acute therapy to two headache days per week on a regular basis. Based on concerns of overuse, medication-overuse headache, and withdrawal, the use of butalbital-containing analgesics should be limited and carefully monitored. The Allzital limit is set to the maximum of 12 doses per day for acute treatment of 8 headaches per month as this product contains less butalbital than other products. -

Migraine: Spectrum of Symptoms and Diagnosis

KEY POINT: MIGRAINE: SPECTRUM A Most patients develop migraine in the first 3 OF SYMPTOMS decades of life, some in the AND DIAGNOSIS fourth and even the fifth decade. William B. Young, Stephen D. Silberstein ABSTRACT The migraine attack can be divided into four phases. Premonitory phenomena occur hours to days before headache onset and consist of psychological, neuro- logical, or general symptoms. The migraine aura is comprised of focal neurological phenomena that precede or accompany an attack. Visual and sensory auras are the most common. The migraine headache is typically unilateral, throbbing, and aggravated by routine physical activity. Cutaneous allodynia develops during un- treated migraine in 60% to 75% of cases. Migraine attacks can be accompanied by other associated symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, gastroparesis, di- arrhea, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, lightheadedness and vertigo, and constitutional, mood, and mental changes. Differential diagnoses include cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoenphalopathy (CADASIL), pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis, ophthalmoplegic mi- graine, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, mitochondrial disorders, encephalitis, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, and benign idiopathic thunderclap headache. Migraine is a common episodic head- (Headache Classification Subcommittee, ache disorder with a 1-year prevalence 2004): of approximately 18% in women, 6% inmen,and4%inchildren.Attacks Recurrent attacks of headache, consist of various combinations of widely varied in intensity, fre- headache and neurological, gastrointes- quency, and duration. The attacks tinal, and autonomic symptoms. Most are commonly unilateral in onset; patients develop migraine in the first are usually associated with an- 67 3 decades of life, some in the fourth orexia and sometimes with nausea and even the fifth decade. -

Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules

Medication Guide Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules, C III Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules are: • A strong prescription pain medicine that contains an opioid (narcotic) that is indicated for the relief of the symptom complex of tension (or muscle contraction) headache, when other pain treatments such as non-opioid pain medicines do not treat your pain well enough or you cannot tolerate them. • An opioid pain medicine that can put you at risk for overdose and death. Even if you take your dose correctly as prescribed you are at risk for opioid addiction, abuse, and misuse that can lead to death. Important information about Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules: • Get emergency help right away if you take too much Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules (overdose). When you first start taking Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules, when your dose is changed, or if you take too much (overdose), serious or life-threatening breathing problems that can lead to death may occur. • Taking Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules with other opioid medicines, benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other central nervous system depressants (including street drugs) can cause severe drowsiness, decreased awareness, breathing problems, coma, and death. • Never give anyone else your Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules. They could die from taking it. Store Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules away from children and in a safe place to prevent stealing or abuse. Selling or giving away Butalbital, Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules is against the law. • Get emergency help right away if you take more than 4,000 mg of acetaminophen in 1 day. -

Hormonal Contraceptive Treatment May Reduce the Risk of Fibromyalgia in Women with Dysmenorrhea: a Cohort Study

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article Hormonal Contraceptive Treatment May Reduce the Risk of Fibromyalgia in Women with Dysmenorrhea: A Cohort Study Cheng-Hao Tu 1,* , Cheng-Li Lin 2, Su-Tso Yang 3,4, Wei-Chih Shen 5,6 and Yi-Hung Chen 1,7,8,* 1 Graduate Institute of Acupuncture Science, China Medical University, Taichung 404333, Taiwan 2 Management Office for Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404332, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Medical Imaging, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404332, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 School of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 404333, Taiwan 5 Center of Augmented Intelligence in Healthcare, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404332, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Asia University, Taichung 413305, Taiwan 7 Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University, Taichung 404333, Taiwan 8 Department of Photonics and Communication Engineering, Asia University, Taichung 41354, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.-H.T.); [email protected] (Y.-H.C.); Tel.: +886-4-22053366 (C.-H.T.) (ext. 3336) Received: 17 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 14 December 2020 Abstract: Dysmenorrhea is the most common gynecological disorder for women in the reproductive age. Study has indicated that dysmenorrhea might be a general risk factor of chronic pelvic pain and even chronic non-pelvic pain, such as fibromyalgia. We used the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 from the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes Database to investigate whether women with dysmenorrhea have a higher risk of fibromyalgia and whether treatment of dysmenorrhea reduced the risk of fibromyalgia. -

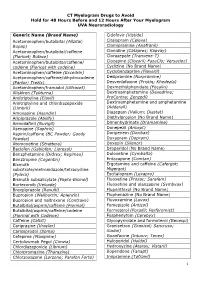

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Migraine Headache Prophylaxis Hien Ha, Pharmd, and Annika Gonzalez, MD, Christus Santa Rosa Family Medicine Residency Program, San Antonio, Texas

Migraine Headache Prophylaxis Hien Ha, PharmD, and Annika Gonzalez, MD, Christus Santa Rosa Family Medicine Residency Program, San Antonio, Texas Migraines impose significant health and financial burdens. Approximately 38% of patients with episodic migraines would benefit from preventive therapy, but less than 13% take prophylactic medications. Preventive medication therapy reduces migraine frequency, severity, and headache-related distress. Preventive therapy may also improve quality of life and prevent the progression to chronic migraines. Some indications for preventive therapy include four or more headaches a month, eight or more headache days a month, debilitating headaches, and medication- overuse headaches. Identifying and managing environmental, dietary, and behavioral triggers are useful strategies for preventing migraines. First-line med- ications established as effective based on clinical evidence include divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol. Medications such as ami- triptyline, venlafaxine, atenolol, and nadolol are probably effective but should be second-line therapy. There is limited evidence for nebivolol, bisoprolol, pindolol, carbamazepine, gabapentin, fluoxetine, nicardipine, verapamil, nimodipine, nifedipine, lisinopril, and candesartan. Acebutolol, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and telmisartan are ineffective. Newer agents target calcitonin gene-related peptide pain transmission in the migraine pain pathway and have recently received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; how- ever, more studies of long-term effectiveness and adverse effects are needed. The complementary treatments petasites, feverfew, magnesium, and riboflavin are probably effective. Nonpharmacologic therapies such as relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, electromyographic feedback, and cognitive behavior therapy also have good evidence to support their use in migraine prevention. (Am Fam Physician. 2019; 99(1):17-24. -

Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Medical Disorders

REVIEW ARTICLE Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Medical Disorders Allison M. Case, MD; Robert L. Reid, MD xacerbation of certain medical conditions at specific phases of the menstrual cycle is a well-recognized phenomenon. We review the effects of the menstrual cycle on medical conditions, including menstrual migraine, epilepsy, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, and diabetes. We discuss the role of medical suppression of ovulationE using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in the evaluation and treatment of these disorders. Peer-reviewed publications from English-language literature were located via MEDLINE or from bibliographies of relevant articles. We reviewed all review articles, case reports and series, and therapeutic trials. Emphasis was placed on diagnosis and therapy of menstrual cycle– related exacerbations of disease processes. Abrupt changes in the concentrations of circulating ovar- ian steroids at ovulation and premenstrually may account for menstrual cycle–related changes in these chronic conditions. Accurate documentation of symptoms on a menstrual calendar allows identification of women with cyclic alterations in disease activity. Medical suppression of ovula- tion using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be useful for both diagnosis and treat- ment of any severe, recurrent menstrual cycle–related disease exacerbations. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1405-1412 The menstrual cycle, an event that punctu- Several theories have been proposed to ates the lives of most women, may be asso- explain these menstrual cycle–related effects ciated with diverse physical, psychological, on existing disease processes, including fluc- and behavioral changes. Not surprisingly, it tuations in levels of sex steroids, cyclic alter- plays a significant role in women’s health and ations in the immune system, and changing disease. -

Drug Plasma Half-Life and Urine Detection Window | January 2019

500 Chipeta Way | Salt Lake City, UT 84108-1221 Phone: (800) 522-2787 | Fax: (801) 583-2712 www.aruplab.com | www.arupconsult.com DRUG PLASMA HALF-LIFE AND URINE DETECTION WINDOW | JANUARY 2019 URINE- PLASMA DRUG, DRUG METABOLITE(S)* COMMON TRADE AND STREET NAMES, NOTES DETECTION HALF-LIFEt WINDOWt STIMULANTS Benzedrine, dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse, speed; could be methamphetamine Amphetamine 7–34 hours 1–5 days metabolite; if so, typically < 30 percent of parent Cocaine Coke, crack; parent drug rarely observed due to short half-life 0.7–1.5 hours < 1 day Benzoylecgonine Cocaine metabolite 5.5–7.5 hours 1–2 days Desoxyn, methedrine, Vicks inhaler (D- and L-isomers not resolved; low concentrations Methamphetamine expected if the source is Vicks); selegeline (Atapryl, Carbex, Eldepryl, Zelapar) 6–17 hours 1–5 days metabolite Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) MDA 11–17 hours 1–3 days Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) MDEA, MDE, Eve 6–11 hours 1–3 days Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) MDMA, XTC, ecstasy, Molly 6–10 hours 1–3 days Methylphenidate Ritalin, Concerta, Focalin, Metadate, Methylin 1.4–4.2 hours < 1 day Ritalinic acid Methylphenidate metabolite 1.8–2.5 hours < 1 day Phentermine Adipex-P, Lomaira, Qsymia 19–24 hours 1–5 days OPIOIDS Buprenorphine Belbuca, Buprenex, Butrans, Suboxone, Subutex, Sublocade, Zubsolv 26–42 hours 1–7 days Norbuprenorphine, Glucuronides Buprenorphine metabolites 15–150 hours 1–14 days Included in many preparations; morphine metabolite; may be a contaminant if < 2 Codeine 1.9–3.9 hours 1–3 days percent of morphine Fentanyl Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, Lazanda, Sublimaze, Subsys, Ionsys 3–12 hours 1–3 days Norfentanyl Fentanyl metabolite 9–10 hours 1–3 days Heroin Diacetylmorphine, dope, smack, dust; parent drug not detected. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Migraine and Tension Headache Guideline

Migraine and Tension Headache Guideline Major Changes as of May 2021 .................................................................................................................... 2 Medications Not Recommended for Headache Treatment .......................................................................... 2 Background ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis Red flag warning signs ........................................................................................................................... 3 Differential diagnosis .............................................................................................................................. 3 Imaging ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Migraine versus tension headache ......................................................................................................... 4 Medication overuse headache ................................................................................................................ 4 Menstruation-related migraine ................................................................................................................ 4 Tension Headache Acute treatment ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Prophylaxis ............................................................................................................................................