Iron Smelting in Vinland Converting Archaeological Evidence to a Practical Method

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Westward Viking Festival: a Real Taste of Vinland Celebrate with Us! July 21-31, 2013

The Westward Viking Festival: a Real Taste of Vinland Celebrate with us! July 21-31, 2013 Join us for the 2nd annual Westward Viking Festival: a Real Taste of Vinland in enchanting L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador. Held each year for the ten days of July 21-31st, we invite you to join in the celebrations and experience the cultural and natural wonders of the Northern Peninsula: Walk back in time along the Birchy Nuddick trail at L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic site and experience a living Viking encampment at three reconstructed sod huts. Forge iron nails with Ragnar the blacksmith or learn single-needle knitting from the Chief’s wife, Thora. At Norstead, join costumed interpreters in the dim light of the Viking-style Chieftain's Hall. Step aboard the full-scale replica Viking ship "Snorri". Enjoy a campfire complete with stories, mussel boil and musical entertainment. Introduce yourself to a pair of loyal and affable Newfoundland dogs. Tour the bogs of St. Lunaire-Griquet, soon to be resplendent with berries, and taste some of The Dark Tickle Company’s delicious products. Dance the night away to traditional Irish/Newfoundland music and become an honorary Newfoundlander at one of the island’s famous activities for come-from-aways – a Screech-in – at Skipper Hot’s Lounge in Straitsview. Experience the old-fashioned Newfoundland tradition of mummering at Northern Delight Restaurant in Gunners Cove, and taste their wonderful cloudberry (bakeapple) desserts. Enjoy tapas and martinis made with local berries and iceberg ice (the purest ice on the planet!) at the Norseman Restaurant. -

OCTOBER 2011 Third District Today

3D OCTOBER 2011 Third District Today The mission of Sons of Norway is to promote and to preserve the heritage and culture of Norway, to celebrate our relationship with other Nordic countries, and to provide quality insurance and financial products to its members. Fra Presidenten Ralph Peterson Hei alle sammen. I hope that you had a great summer and were not affected by Irene (Hurricane Irene that is) or any of the other nasty storms that we have so far experienced this season. Hopefully that type of weather is gone for a while. Following up on my last letter we did see some moose before we left Newfoundland and they were not in the road or my headlights. They were huge and seemed to be as interested in us as we were with them. As I said before, the trips on Hurtigruten and to L’Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland have to be two of the greatest trips that I have made. The planning for our convention and centennial celebration continues. Thus far only 30 lodges have submitted lodge histories to our Centennial Editor, Asbjorn Lageraaen. For the remaining lodges, please make every effort to send your lodge history to Asbjorn so we have a book with all lodge histories in our centennial book. By the time you get this letter we should have a “convention /centennial page” on the web site. We will shortly send you (those with email address listed on the SON web site) a note via our new “constant contact” program with more info on the events as well. -

Annette Kolodny in Search of First Contact

In Search of First Contact The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo-American Anxiety of Discovery Annette Kolodny In Search of First Contact The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo- American Anxiety of Discovery ✴ Annette Kolodny Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2012 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Chaparral Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. With DeeP Love anD enDLess gratituDe, this book is DeDicateD to my truest teachers, Past anD Present: Sarah Katz Rivkind and David Rivkind, doting grandparents who believed I could do no wrong Esther Rivkind Kolodny, my loving mother who did her best Blanche Gladstone, P.S. 139, Brooklyn, New York Harriet Knight Felder, Erasmus Hall High School, Brooklyn, New York Lillian Fischer Schlissel, Brooklyn College, New York Odd Nordland, University of Oslo, Norway Odd- Erik Bjarre, Oslo, Norway Stanley E. Fish, University of California, Berkeley Norman S. Grabo, University of California, Berkeley Mark Schorer, University of California, Berkeley Henry Nash Smith, University of California, Berkeley Dorothee Finkelstein, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut C. Hugh Holman, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Per Seyersted and Brita Lindberg Seyersted, University of Oslo, Norway Gary Lindberg, University of New Hampshire, Durham Patricia Clark Smith, Mi´kmaq, University of New Mexico Arnie Neptune, Penobscot Nation elder and leader of ceremonies Wayne Newell, Passamaquoddy elder and educator James G. -

Valuing Immigrant Memories As Common Heritage

Valuing Immigrant Memories as Common Heritage The Leif Erikson Monument in Boston TORGRIM SNEVE GUTTORMSEN This article examines the history of the monument to the Viking and transatlantic seafarer Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) that was erected in 1887 on Common- wealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts. It analyzes how a Scandinavian-American immigrant culture has influenced America through continued celebration and commemoration of Leif Erikson and considers Leif Erikson monuments as a heritage value for the public good and as a societal resource. Discussing the link between discovery myths, narratives about refugees at sea and immigrant memo- ries, the article suggests how the Leif Erikson monument can be made relevant to present-day society. Keywords: immigrant memories; historical monuments; Leif Erikson; national and urban heritage; Boston INTRODUCTION At the unveiling ceremony of the Leif Erikson monument in Boston on October 29, 1887, the Governor of Massachusetts, Oliver Ames, is reported to have opened his address with the following words: “We are gathered here to do honor to the memory of a man of whom indeed but little is known, but whose fame is that of having being one of those pioneers in the world’s history, whose deeds have been the source of the most important results.”1 Governor Ames was paying tribute to Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) from Iceland, who, according to the Norse Sagas, was a Viking Age transatlantic seafarer and explorer.2 At the turn History & Memory, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2018) 79 DOI: 10.2979/histmemo.30.2.04 79 This content downloaded from 158.36.76.2 on Tue, 28 Aug 2018 11:30:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen of the nineteenth century, the story about Leif Erikson’s being the first European to land in America achieved popularity in the United States. -

Norse America

BULLFROG FILMS PRESENTS NORSE AMERICA Study Guide by Thomas H. McGovern NORSE AMERICA 56 minutes Produced & Directed by T.W. Timreck and W.N. Goetzmann in association with the Arctic Studies Center at Smithsonian Institution VHS videos and DVDs available for rental or purchase from Bullfrog Films® ©1997 Bullfrog Films, Inc. Guide may be copied for educational purposes only. Not for resale. NORSE AMERICA Study Guide by Thomas H. McGovern North Atlantic Biocultural Organization Anthropology Department Hunter College, CUNY 695 Park Ave., New York, N.Y. 10021 SYNOPSIS Norse America introduces the viewer to the latest findings on the Viking-Age voyages across the North Atlantic to North America. It places these medieval transatlantic travels in the wider context of prehistoric maritime adaptations in North Atlantic Europe, and illustrates the continuity of seafaring traditions from Neolithic to early medieval times. The remarkable Norse voyages across the North Atlantic were part of the Scandinavian expansion between AD 750-1000 that saw Viking raids on major European monasteries and cities, long distance trading ventures into central Asia, and the settlement of the offshore islands of the North Atlantic. The impact of Viking raiders on the centers of early medieval literacy are comparatively well-documented in monastic annals and contemporary histories, but the Norse movement westwards into the Atlantic is recorded mainly by modern archaeology and by the semi-fictional sagas produced by the Norsemen themselves. While many of the sagas describe events of the 9th and 10th centuries (complete with memorable dialog and very specific descriptions of scenery), they werefirst written down in the 13th-14th centuries in Iceland. -

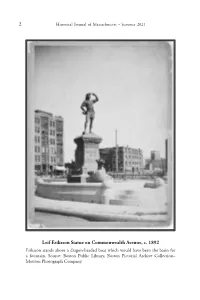

2 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, C. 1892

2 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, c. 1892 Eriksson stands above a dragon-headed boat which would have been the basin for a fountain. Source: Boston Public Library, Boston Pictorial Archive Collection– Mouton Photograph Company. 3 PHOTO ESSAY Vikings on the Charles: Leif Eriksson, Eben Horsford, and the Quest for Norumbega GLORIA POLIZZOTTI GREIS Editor’s Introduction: This colorful and intriguing photo essay traces how and why a statue of Norse explorer Leif Eriksson came to occupy a prominent place on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue in 1877. A group of amateur archaeologists, scholars, and artists, all members of the Boston elite, fostered a growing interest in the theory that Leif Eriksson was the first European to reach North American shores hundreds of years before Columbus. Chemist Eben Horsford invented double-acting baking powder, a lucrative business venture which funded his obsessive interest in proving that Leif Eriksson played a much larger role in the establishment of European settlement on the continent. This photo essay follows his passionate, often misleading, and ultimately discredited contribution to the history of North America. Dr. Gloria Polizzotti Greis is the Executive Director of the Needham History Center and Museum. This is a slightly revised and expanded version of material that was first published on the museum's website.1 * * * * * Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 49 (2), Summer 2021 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 4 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 At the far western end of Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue promenade, Leif Eriksson stands shading his eyes with his hand, surveying the Charlesgate flyover. -

Ingstad, Benedicte. 2017. a Grand Adventure: the Lives of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad and Their Discovery of a Viking Settlement in North America

Document generated on 09/26/2021 3:22 p.m. Material Culture Review Ingstad, Benedicte. 2017. A Grand Adventure: The Lives of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad and Their Discovery of a Viking Settlement in North America. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Diane Chisholm Volume 84, 2016 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/mcr84_br01 See table of contents Publisher(s) Cape Breton University Press ISSN 1718-1259 (print) 0000-0000 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Chisholm, D. (2016). Review of [Ingstad, Benedicte. 2017. A Grand Adventure: The Lives of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad and Their Discovery of a Viking Settlement in North America. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.] Material Culture Review, 84, 81–83. All rights reserved © Cape Breton University Press, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Book Reviews Comptes rendus de livres DIANE CHISHOLM Review of Ingstad, Benedicte. 2017. A Grand Adventure: The Lives of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad and Their Discovery of a Viking Settlement in North America. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Pp. 455. Hardcover. B/w and colour photographs, maps, index. -

04871 Acadiensis Cover

04871-08 Codignola / Review 6/6/02 8:48 AM Page 185 REVIEW ESSAYS/NOTES CRITIQUES North American Discovery and Exploration Historiography, 1993-2001: From Old-Fashioned Anniversaries to the Tall Order of Global History? DISCOVERY AND EXPLORATION have recently become unfashionable, if not altogether disreputable, subjects of study among historians of early North America and of the North Atlantic world. Even the term “discovery” and its apparently more correct substitute, “encounter”, have fallen into disgrace because such terms allegedly give only a European point of view.1 Certainly, as the illustrious British cartographer Helen Wallis has noted, everybody acknowledges that a selected number of historians have provided the international scholarly community with the records “of the feats of exploration and discovery”, that enable their peers “to assess the achievements, to allocate the credits and sometimes the blames”. The names of French Charles-André Julien (1891-1991), Americans Carl Ortwin Sauer (1889-1975) and Louis André Vigneras, British Charles Ralph Boxer (1904-2000), John Horace Parry (1914-82), David Beers Quinn, Raleigh Ashlin Skelton (1906-70) and James Alexander Williamson (1886-1964) immediately spring to mind. Without such records, as British Africanist historians Roy C. Bridges and Paul E.H. Hair (1926-2001) observe, “there can be no interpretations, valid or otherwise, indeed no serious history”. Yet a statement by Quinn, perhaps the most prominent contributor to the field of early North Atlantic discovery, that he “feel[s] that perhaps [he has] been better in documentation and descriptive writing rather than in analysis”, would today be considered naive if it came from any graduate student.2 “Contact” is the accepted buzz-word that replaced both “discovery” and “exploration”. -

Foreword Look for It: the Coastlines Around the Gulf of St

evidence at L’Anse aux Meadows has given us a strong pointer where to Foreword look for it: the coastlines around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, with L’Anse aux Meadows being the Straumfjord of Eirik the Red’s Saga, Vinland’s main by Birgitta Wallace settlement, and the Miramichi and Chaleur Bay area of New Brunswick the warmer and more hospitable Hóp where grapes really do grow wild. Clearly When I arrived in North America in the 1960s I was amazed by Vinland encompasses a vast area, and the Norse may have set foot in many the widespread fascination with Norse Vinland and the Norse themselves, locations. commonly referred to as Vikings. This was particularly striking as, at the The stories presented here are to some extent spurred by theories time, Scandinavians back in their own lands were not particularly interested and a mix of professional and amateur investigations, some undertaken long in their Viking forbearers. This has since changed as the great tourist potential ago and some more recent. Rona Rangsch has presented them as stories, of everything Viking has taken hold. stories that appeal to the imagination as they are, without judgement. To her, One of my first assignments as an archaeologist with Carnegie the driving factor lies in the almost inexplicable fascination with Vinland, Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, PA, was to travel to every alleged the way the Vinland sagas continue to stimulate passion for discovery, for Viking location in North America, to view every artifact, inscription, and site interpretation, and leading to a variety of individual geographic spots and and to give them the same kind of assessment as one would any archaeological objects, here beautifully illustrated and described, dangling between myths phenomenon. -

The Viking Ship Museum the Viking Ship Museum Has the World’S Best‐Preserved Viking Ships

Oslo: The Viking Ship Museum The Viking Ship Museum has the world’s best‐preserved Viking ships. The museum is managed by the University of Oslo. It also includes a Museum of Cultural History, which we were unable to visit. All the ships shown were once used as ocean‐going vessels. Later, they were brought on land and used as burial ships. The statues in front of the museum are of “two Norwegian researchers, Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad, who discovered and excavated the Viking base camp at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland In the 1960s —the first confirmed Viking outpost in the Americas. Dated to between 989 and 1020, the camp boasted three Viking halls, as well as an assortment of huts for weaving, ironworking, and ship repair.” (National Geographic) According to Patricia Sutherland, Canadian archeologist (National Geographic), “Viking seafarers travelled to the Canadian Arctic to search for valuable resources. In northern Europe at the time, medieval nobles prized walrus ivory, soft Arctic furs, and other northern luxuries—and Dorset hunters and trappers could readily stockpile such products. Helluland's waters teemed with walruses, and its coasts abounded in Arctic foxes and other small fur‐bearing animals. To barter for such goods, Viking traders likely offered bits of iron and pieces of wood that could be carved into figurines and other goods.” This photo program shares the sites and a video that shares the exploits of the Vikings from 750‐1060 AD. The Oseberg Ship was built around the year 820 and is richly decorated with detailed carvings. -

Falling Into Vínland Newfoundland Hunting Pitfalls at the Edge of the Viking World

Acta Archaeologica vol. 83, 2012, pp 145-177 Copyright 2012 Printed in Denmark • All rights reserved ACTA ARCHAEOLOGICA ISSN 0065-101X (print) ISSN 1600-0390 (online) FALLING INTO VÍNLAND NEWFOUNDLAND HUNTING PITFALLS AT THE EDGE OF THE VIKING WORLD Jónas Kristjánsson, Bjarni F. Einarsson, Kristján Jónasson, Kevin McAleese & Þór Hjaltalín ABSTRACT. Two interwoven topics are dealt with, fi rst- could be Sop’s Arm in White Bay on the North coast of ly a new interpretation of the Icelandic Sagas and histor- Newfoundland. The system of pitfalls that was surveyed ical written sources on the Viking age voyages to North and excavated is close to Sop’s Arm. The pitfalls form an America, leading to a theory on the location of Vínland, 82 metre long system that lies in an almost straight line. and secondly an archaeological survey of deer hunting Individual pits are now 1.5–2.3 metres deep and 7–10 pitfalls in Newfoundland, which were possibly dug by the metres long. Two pitfalls were excavated by taking a sec- Nordic voyagers a millenium ago. According WR the theory tion into them. Attempted radiocarbon dating of soil from of the article, Vínland is the modern day Newfoundland, two pitfalls was inconclusive. Considerable soil thicken- and the Straumfjord of the sagas, where Thorfi nn Karl- ing of 55–110 centimetres since the pitfall construction sefni and Gudríd Thorbjarnardóttir attempted settlement was observed. 1. INTRODUCTION Several written sources dating from the 11th, 12th and One of the authors of the article, Kevin McAleese is 13th centuries tell about the discovery of North America only responsible for Aboriginal and non-Norse settlement by Icelanders and Greenlanders around the year 1000 AD. -

Christian Keller Furs, Fish and Ivory – Medieval Norsemen at the Arctic Fringe

1 SUBMISSION OF PAPER TO THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC (JONA) Christian Keller Furs, Fish and Ivory – Medieval Norsemen at the Arctic Fringe DECLARATION: This paper was originally written after a discussion at a conference in Aberdeen in 2004, and was submitted for publication in the Proceedings of that conference in 2005. For reasons unknown to me, the Proceedings were never published, but the manuscript had been submitted and I needed a confirmation that I could submit it for publication elsewhere. This confirmation was finally received this fall (September 2008). The text has now been upgraded and relevant literature published since 2005 added, hopefully making it a completely up-to-date paper suited for publication. All the illustrations have been drawn by me. CONTENTS The paper sees the Norse colonization of Greenland and the exploratory journeys on the Canadian East Coast as resulting from an adaptation to the European luxury market for furs and ivory. The Norse expansion into the Western Arctic is compared to the Norse expansion into the territories of the Sámi and Finnish hunter-gatherers North and East of Scandinavia. The motivation for this expansion was what is often called the coercion-and- extortion racket, aimed at extracting furs from the local tribes (called “taxation”) for the commercial markets in Western Europe and in the Middle East. The Norse adventures in the West Atlantic are seen as expressions of the same economic strategy. Icelanders were, after all, quite familiar with the Norse economic activities North and East of Scandinavia. This comparative approach is original, and it makes the Norse expansion in the West Atlantic appear less exotic and more “in character with the Norse” than normally expressed in the academic literature.