On the Eve of the Summit: Options for U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Government Fund Contributions to Candidates and Political Committees January 1 ‐ December 31, 2018

GOOD GOVERNMENT FUND CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018 STATE RECIPIENT OF GGF FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE CA Jeff Denham, Jeff PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC DC Association of American Railroads PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Trade Assn PAC FL Bill Nelson, Moving America Forward PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA David Perdue, One Georgia PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA Johnny Isakson, 21st Century Majority Fund Fed $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC MO Roy Blunt, ROYB Fund $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC NE Deb Fischer, Nebraska Sandhills PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC OR Peter Defazio, Progressive Americans for Democracy $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SC Jim Clyburn, BRIDGE PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SD John Thune, Heartland Values PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC US Dem Cong Camp Cmte (DCCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Cong Cmte (NRCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Dem Sen Camp Cmte (DSCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Sen Cmte (NRSC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct VA Mark Warner, Forward Together PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC VA Tim Kaine, Common -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 6, 2017 No. 96 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was securing the beachhead. The countless Finally, in March 2016, after 64 years called to order by the Speaker pro tem- heroes who stormed the beaches of Nor- and extensive recovery efforts, Staff pore (Mr. BERGMAN). mandy on that fateful day 73 years ago Sergeant Van Fossen’s remains were f will never be forgotten. confirmed found and returned to his I had the honor of visiting this hal- home in Heber Springs, Arkansas. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO lowed ground over Memorial Day, and I would like to extend my deepest TEMPORE while I was paying tribute to the brave condolences to the family of Staff Ser- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- soldiers who made the ultimate sac- geant Van Fossen and hope that they fore the House the following commu- rifice at the Normandy American Cem- are now able to find peace that he is fi- nication from the Speaker: etery and Memorial, an older French- nally home and in his final resting man by the name of Mr. Vonclair ap- place. WASHINGTON, DC, proached me simply wanting to honor June 6, 2017. CONWAY BIKESHARE PROGRAM I hereby appoint the Honorable JACK his liberators. He said that he just Mr. HILL. Mr. Speaker, last month BERGMAN to act as Speaker pro tempore on wanted to thank an American. -

Venezuela's Tragic Meltdown Hearing

VENEZUELA’S TRAGIC MELTDOWN HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 28, 2017 Serial No. 115–13 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–831PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 12:45 May 02, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_WH\032817\24831 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. YOHO, Florida DINA TITUS, Nevada ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois NORMA J. -

2018 MIDTERM ELECTION RECAP Monday, January 28, 2019 9:30Am – 10:30Am – Room: M107 Presenter: Andrew Newhart 115Th CONGRESS

2018 MIDTERM ELECTION RECAP Monday, January 28, 2019 9:30am – 10:30am – Room: M107 Presenter: Andrew Newhart 115th CONGRESS 2018 = Republicans control both chambers U.S. Senate House of Representatives 51-R v. 47-D v. 2-I 235-R v. 193-D 7 - vacant 2 MIDTERM RESULTS ▪ SEATS UP ✓ House = 435 seats of 435 - 218 seats to control - D’s needed 23 seats for control – flipped 40 ✓ Senate = 35* seats of 100 ✓ 26 of 35 - held by Ds, including 2 I’s ✓ 9 of 35 – held by Rs ✓ D’s needed 2 seats for control – lost 2 ▪ UNCALLED RACES ✓ NORTH CAROLINA HOUSE DISTRICT 9 3 HOUSE MAP 4 SENATE MAP 5 BALANCE OF POWER 6 116th CONGRESS Republican Controlled Senate | Democratic Controlled House United States Senate House of Representatives 53-R v. 47-D 227-D v. 198-R 1 uncalled 7 CURRENT STATUS U.S. Federal Government 8 SENATE COMMERCE COMMITTEE Republicans Democrats Roger Wicker (MS) Chair Maria Cantwell (WA) John Thune (SD) Amy Klobuchar (MN) Roy Blunt (MO) Brian Schatz (HI) Deb Fischer (NE) Tom Udall (NM) Dan Sullivan (AK) Tammy Baldwin (WI) Ron Johnson (WI) Jon Tester (MT) Cory Gardner (CO) Richard Blumenthal (CT) Ted Cruz (TX) Ed Markey (MA) Jerry Moran (KS) Gary Peters (MI) Mike Lee (UT) Tammy Duckworth (IL) Shelley Moore Capito (WV) Krysten Sinema (AZ) Todd Young (IN) Jacky Rosen (NV) Rick Scott (FL) Marsha Blackburn (TN) 9 HOUSE TRANSPORTATION & INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE Democrats Democrats Republicans Republicans Peter DeFazio (OR) – Chair Donald Payne (NJ) Sam Graves (MO) Lloyd Smucker (PA) Eleanor Holmes Norton (DC) Alan Lowenthal (CA) Don Young (AK) -

April 24, 2020 (Florida Federal Qualifying) Report

2020 Florida Federal Candidate Qualifying Report / Finance Reports Cumulative Totals through March 31, 2020 Office Currently Elected Challenger Party Contributions Expenditures Total COH CD01 Matt Gaetz REP $ 1,638,555.81 $ 1,284,221.76 $ 496,295.82 CD01 Phil Ehr DEM $ 342,943.79 $ 188,474.53 $ 154,469.26 CD01 Greg Merk REP $ - $ - $ - CD01 John Mills REP $ 5,000.00 $ 5,132.61 $ 145.02 CD01 Albert Oram* NPA CD02 Neal Dunn REP $ 297,532.04 $ 264,484.41 $ 419,201.78 CD02 Kim O'Connor* WRI CD02 Kristy Thripp* WRI CD03 OPEN - Ted Yoho REP CD03 Kat Cammack REP $ 207,007.59 $ 41,054.05 $ 165,953.54 CD03 Ryan Chamberlin REP $ 101,333.00 $ 4,025.39 $ 97,307.61 CD03 Todd Chase REP $ 163,621.68 $ 27,032.07 $ 136,589.61 CD03 Adam Christensen DEM $ - $ - $ - CD03 Philip Dodds DEM $ 6,301.17 $ 4,035.13 $ 2,266.04 CD03 Bill Engelbrecht REP $ 27,050.00 $ 4,955.94 $ 22,094.06 CD03 Joe Dallas Millado* REP CD03 Gavin Rollins REP $ 106,370.00 $ 9,730.33 $ 96,639.67 CD03 Judson Sapp REP $ 430,233.01 $ 120,453.99 $ 310,011.88 CD03 Ed Silva* WRI CD03 James St. George REP $ 400,499.60 $ 64,207.88 $ 336,291.72 CD03 David Theus REP $ 6,392.11 $ 473.58 $ 5,918.53 CD03 Amy Pope Wells REP $ 56,982.45 $ 46,896.17 $ 10,086.28 CD03 Tom Wells DEM $ 1,559.31 $ 1,289.68 $ 295.58 CD04 John Rutherford REP $ 513,068.32 $ 281,060.16 $ 597,734.31 CD04 Erick Aguilar REP $ 11,342.00 $ 6,220.00 $ 5,122.00 CD04 Donna Deegan DEM $ 425,901.36 $ 165,436.85 $ 260,464.51 CD04 Gary Koniz* WRI CD05 Al Lawson DEM $ 355,730.10 $ 168,874.69 $ 201,527.67 CD05 Gary Adler REP $ 40,325.00 $ 920.08 $ 39,404.92 CD05 Albert Chester DEM $ 43,230.65 $ 28,044.61 $ 15,186.04 CD05 Roger Wagoner REP $ - $ - $ - CD06 Michael Waltz REP $ 1,308,541.18 $ 626,699.95 $ 733,402.64 CD06 Clint Curtis DEM $ 13,503.79 $ 1,152.12 $ 12,351.67 CD06 Alan Grayson WRI $ 69,913.27 $ 56,052.54 $ 716,034.49 CD06 John. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

Endorsement Guide 2020 Florida Primary Elections

FLORIDA VOTER ENDORSEMENT GUIDE 2020 FLORIDA PRIMARY ELECTIONS ENDORSEMENT ALLY PREFERRED AN ENDORSEMENT RATING indicates AN ALLY RATING indicates two or more A PREFERRED RATING indicates a candi- a vetted and recommended candidate candidates meeting all or most of the date(s) preferred as more conservative or based on a conservative voting record; endorsement standards, but who do more competent than the other candidate/s personal interviews or knowledge of not have significant enough differences running in the same race but who cannot the candidate; or thorough research to merit an endorsement rating for one be fully supported with an endorsement. showing a conservative background, candidate over the other(s). In this case, Preferred status may indicate no voting training, and experience. Endorsement all such rated candidates are counted as record to validate claims of being conser- indicates a very high likelihood of confi- acceptable, conservative candidates. vative; a mixed voting record; or all the dence that this candidate will govern and candidates are either mediocre or weak vote as a conservative. and we are simply recommending the slightly better candidate(s). U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT DISTRICT DISTRICT 1 Greg Merk (R) 10 Vennia Francois (R) 20 Vic DeGrammont (R) 3 Gavin Rollins (R) 13 Anna Paulina Luna (R) 21 Laura Loomer (R) 4 John Rutherford (R) * 14 Paul Sidney Elliot (R) 22 James “Jim” Pruden (R) 7 Richard Goble (R) 15 Ross Spano (R) * 23 Carla Spaulding (R) 8 Bill Posey (R) * 16 Brian Mast (R) * 26 Carlos -

March 4, 2021 President Joe Biden the White House 1600

March 4, 2021 President Joe Biden The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: As you finalize your inaugural budget request for Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22), we respectfully urge you to request robust funding for Everglades restoration to support the expeditious completion of numerous projects that are integral to the success of restoration efforts. Specifically, we ask that you include $725 million in the FY22 budget proposal under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) construction account for South Florida Ecosystem Restoration (SFER). The Everglades is central to Florida’s ecological and economic health, and is the source of drinking water for 8 million Floridians. Restoration of this irreplaceable resource would ensure economic security and a reliable and clean water supply for communities for generations to come. Also, the greater Everglades system supports irreplaceable natural infrastructure that impedes storm surge, saltwater intrusion, and the impacts of sea level rise. As you seek to identify large-scale projects that support economic development and natural climate solutions, we urge you to consider Everglades restoration as a commonsense option for making major progress on such efforts. Florida’s environmental assets attracted 131 million visitors in 2019, directly infusing nearly $100 billion into the state’s economy. Environmental disasters in years prior, such as severe harmful algal blooms, undermined economic stability in communities whose economies are completely dependent on a clean environment. In 2018, environmental disasters related to harmful algal blooms caused tens of millions of dollars in economic losses in some communities, resulting in lost incomes for workers that threatened their ability to feed their families. -

Letter 4.1 All Pages

The Honorable Ron DeSantis Office of Governor Ron DeSantis State of Florida The Capitol 400 S. Monroe St. Tallahassee, FL 32399 Dear Governor DeSantis: We write to request, urgently, that you immediately take all possible steps, together with the state and federal governments, to, first and foremost, procure a field hospital in Immokalee to address the COVID-19 pandemic, and also to conduct aggressive, proactive COVID-19 testing and distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE), including sufficient quantities of sanitizer, in Immokalee. Unless this is done, Immokalee will almost certainly become an epicenter of contagion, with dire consequences not only for the farmworker community in Immokalee and the broader Southwest Florida area, but also the Florida agricultural industry and the food supply of the entire United States. There is no sugar-coating the facts: Immokalee is uniquely vulnerable due to a combination of critical factors, including: 1) overcrowded housing and transportation conditions; 2) the designation of agriculture as an essential industry during this pandemic; and 3) a near total lack of access to medical care and resources even before COVID-19. Overcrowded Housing and Transportation. Overcrowding is endemic in and around Immokalee, both at home and at work. As documented in the Collier County Needs Assessment for 2016-2020, “[h]ousing stock in Immokalee is not sufficient to meet the needs of the existing workforce,” but rather consists in large part of mobile homes that are “often run down and overpopulated.”1 And while grower-provided farmworker housing is generally compliant with the legally mandated 50 square feet per worker, that too is totally inadequate to meet the demands for social separation and quarantine once COVID-19 takes root. -

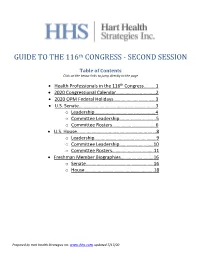

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

December 31, 2019

Microsoft Corporation Tel 425 882 8080 One Microsoft Way Fax 425 936 7329 Redmond, WA 98052-6399 http://wwww.microsoft.com Microsoft Political Action Committee Federal Candidate Contributions July 1, 2019 - December 31, 2019 Candidate State Office Amount Rep. Adrian Michael Smith (R) NE United States House of Representatives $ 2,000 Rep. Alma Shealey Adams (D) NC United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Garland Hale Barr, IV (R) KY United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Angela Dawn Craig (D) MN United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Anna G. Eshoo (D) CA United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Anthony Gregory Brown (D) MD United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Anthony Gregory Brown (D) MD United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Anthony E Gonzalez (R) OH United States House of Representatives $ 2,000 Rep. Anthony E Gonzalez (R) OH United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Kelly M. Armstrong (R) ND United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Kelly M. Armstrong (R) ND United States House of Representatives $ 2,500 Rep. Kelly M. Armstrong (R) ND United States House of Representatives $ 2,500 Rep. Joyce Beatty (D) OH United States House of Representatives $ 1,500 Rep. Benjamin L. Cline (R) VA United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Jack Bergman (R) MI United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. Andrew S. Biggs (R) AZ United States House of Representatives $ 1,000 Rep. William H. Long, II (R) MO United States House of Representatives $ 1,500 Rep. -

DCN Subject Received Input Date to (Recipient) from (Author) EST-00005648 on Behalf of C.C

DCN Subject Received Input Date To (Recipient) From (Author) EST-00005648 On behalf of C.C. and removing house off National 11/03/2017 11/03/2017 Micah Chambers Cheri Bustos EST-00005638 Regarding a DOI OIG issue. 11/02/2017 11/03/2017 Christopher Michelle Grisham Mansour EST-00005637 Urge you to include increased funding for USGS 11/02/2017 11/03/2017 Ryan Zinke Earl Blumenauer, Julia Brownley, Derek Kilmer, Judy Chu, Adam earthquake-related programs. Schiff, Salud Carbajal, Suzanne Bonamici, Peter DeFazio, Tony Cardenas, Suzan K. DelBene + 24 EST-00005561 Monument Review 10/31/2017 11/02/2017 Ryan Zinke Tom Udall, Jeff Merkley, Martin Heinrich, Richard Durbin EST-00005559 Rep. Alma Adams re: Catawba Indian Nation's 10/25/2017 11/01/2017 Ryan Zinke Alma Adams Land in Trust Request for King' s Mountain EST-00005555 asks Department to help combat outbreak of cattle 11/01/2017 11/01/2017 Ryan Zinke John Cornyn, Texas Delegation, Ted Cruz + 37 tick fever on ranches in south and central Texas EST-00005533 Senator Lankford re: Constituent JT - request for 10/06/2017 11/01/2017 OCL James Lankford EST-00005517 Status Report: Social Security Number Fraud 11/01/2017 11/01/2017 Ryan Zinke Sam Johnson, Mark Meadows EST-00005501 National Park Service Project # 34145 & 34159; 10/26/2017 10/31/2017 Ryan Zinke Bill Cassidy redevelopment and rooftop addition to NewOrleans EST-00005500 supports Save the Redwoods League's application 10/30/2017 10/31/2017 Ryan Zinke Dianne Feinstein for funding from the Land and Water Conservation EST-00005498 Supports inclusion of Beaver Valley as part of First 10/30/2017 10/31/2017 Ryan Zinke Patrick Meehan State National Historic Park in Pennsylvania EST-00005495 concern about proposed fee increase for national 10/27/2017 10/31/2017 Ryan Zinke Susan Collins, Angus, Jr.