Evidence from Rainfall Variation and Terrorist Attacks in Pakistan∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan Muhammad Shahbaz Chattha Women University Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Bagh (AJK), [email protected] Abu Ul Hassan Faiz Women University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Bagh (AJK), [email protected] Arshad Javid University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences, Lahore, [email protected] Irfan Baboo Cholistan University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences, Bahawalpur, [email protected] Inayat Ullah Malik The University of Lakki Marwat, Lakki Marwat, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Entomology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Chattha, M. S., Faiz, A. H., Javid, A., Baboo, I., & Malik, I. U. (2018). Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan, Journal of Bioresource Management, 5 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.35691/JBM.8102.0081 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 16, 2019; Accepted: Sep 19, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2018) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. -

Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur by Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 2, No. 2 (2010) Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur By Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani Geographical introduction: The Bahawalpur State was situated in the province of Punjab in united India. It was established by Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan I in 1739, who was granted a title of Nawab by Nadir Shah. Technically the State, had come into existence in 1702 (Aziz, 244, 2006).1 According to the first English book on the State of Bahawalpur, published in mid 19th century: … this state was bounded on east by the British possession of Sirsa, and on the west by the river Indus; the river Garra forms its northern boundary, Bikaner and Jeyselmeer are on its southern frontier…its length from east to west was 216 koss or 324 English miles. Its breadth varies much: in some parts it is eighty, and in other from sixty to fifteen miles. (Ali, Shahamet, b, 1848) In the beginning of the 20th century, this State lay in the extreme south- west of the Punjab province, between 27.42’ and 30.25’ North and 69.31’ and 74.1’ East with an area of 15,918 square miles. Its length from north-east to south-west was about 300 miles and its mean breadth is 40 miles. Of the total area, 9,881 square miles consists of desert regions with sand-dunes rising to a maximum height of 500 feet. The State consists of 10 towns and 1,008 villages, divided into three Nizamats (administrative Units): Minchinabad, Bahawalpur and Khanpur. -

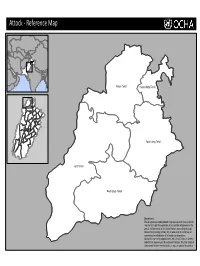

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Field Appraisal Report Tma Ferozewala

FIELD APPRAISAL REPORT TMA FEROZEWALA Prepared by; Punjab Municipal Development Fund Company December-2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 1.1 BACKGROUND 2 1.2 METHODOLOGY 2 1.3 DISTRICT PROFILE 2 1.3.1 History 2 1.3.2 Location 2 1.3.3 Area/Demography 2 1.4 TMA/TOWN PROFILE 3 1.4.1 TMA Status 3 1.4.2 Location 3 1.4.3 Area / Demography 3 1.5 TMA STAFF PROFILE 4 1.6 INSTITUTIONAL ASSESSMENT 4 1.6.1 Tehsil Nazim 4 1.6.2 Office of Tehsil Municipal Officer 4 1.7 TEHSIL OFFICER (Planning) OFFICE 8 1.8 TEHSIL OFFICER (Regulation) OFFICE 10 1.9 TEHSIL OFFICER (Finance) OFFICE 11 1.10 TEHSIL OFFICER (Infrastructure & Services) OFFICE 15 2. INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 2.1 ROADS 17 2.2 WATER SUPPLY 17 2.3 SEWERAGE 18 2.4 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT 18 2.5 FIRE FIGHTING 18 2.6 PARKS 18 1 1. INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 1.1 BACKGROUND TMA Ferozewala has applied for funding under PMSIP. After initial desk appraisal, PMDFC field team visited the TMA for assessing its institutional and engineering capacity. 1.2 METHODOLOGY Appraisal is based on interviews with TMA staff, open-ended and close-ended questionnaires and agency record. Debriefing sessions and discussions were held with Tehsil Nazim, TMO, TOs and other TMA staff. 1.3 DISTRICT PROFILE 1.3.1 History The district of Sheikhupura derives its name from its headquarters town, which was named after the Emperor Jehangir, who founded it and was called by nickname of Sheikhu by his father. -

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research ABSTRACT This report documents the technical support provided by the Design Team, deployed by CDPR, and covers the recommendations for institutional and regulatory reforms as well as a proposed private sector participation framework for tourism sector in Punjab, in the context of religious tourism, to stimulate investment and economic growth. Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project ---------------------- (Back of the title page) ---------------------- This page is intentionally left blank. 2 Consortium for Development Policy Research Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 56 LIST OF FIGURES 78 LIST OF TABLES 89 LIST OF BOXES 910 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1112 1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1819 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1819 1.2 PAKISTAN’S TOURISM SECTOR 1819 1.3 TRAVEL AND TOURISM COMPETITIVENESS 2324 1.4 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF TOURISM SECTOR 2526 1.4.1 INTERNATIONAL TOURISM 2526 1.4.2 DOMESTIC TOURISM 2627 1.5 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL HERITAGE / RELIGIOUS TOURISM 2728 1.5.1 SIKH TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 2930 1.5.2 BUDDHIST TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 3536 1.6 DEVELOPING TOURISM - KEY ISSUES & CHALLENGES 3738 1.6.1 CHALLENGES FACED BY TOURISM SECTOR IN PUNJAB 3738 1.6.2 CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HERITAGE TOURISM 3940 2 EXISTING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM SECTOR 4344 2.1 CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 4344 2.1.1 YOUTH AFFAIRS, SPORTS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND TOURISM -

Punjab Health Statistics 2019-2020.Pdf

Calendar Year 2020 Punjab Health Statistics HOSPITALS, DISPENSARIES, RURAL HEALTH CENTERS, SUB-HEALTH CENTERS, BASIC HEALTH UNITS T.B CLINICS AND MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH CENTERS AS ON 01.01.2020 BUREAU OF STATISTICS PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT BOARD GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE www.bos.gop.pk Content P a g e Sr. No. T i t l e No. 1 Preface I 2 List of Acronym II 3 Introduction III 4 Data Collection System IV 5 Definitions V 6 List of Tables VI 7 List of Figures VII Preface It is a matter of pleasure, that Bureau of Statistics, Planning & Development Board, Government of the Punjab has took initiate to publish "Punjab Health Statistics 2020". This is the first edition and a valuable increase in the list of Bureau's publication. This report would be helpful to the decision makers at District/Tehsil as well as provincial level of the concern sector. The publication has been formulated on the basis of information received from Director General Health Services, Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s), Inspector General (I.G) Prison, Auqaf Department, Punjab Employees Social Security, Pakistan Railways, Director General Medical Services WAPDA, Pakistan Nursing Council and Pakistan Medical and Dental Council. To meet the data requirements for health planning, evaluation and research this publication contain detailed information on Health Statistics at the Tehsil/District/Division level regarding: I. Number of Health Institutions and their beds’ strength II. In-door & Out-door patients treated in the Health Institutions III. Registered Medical & Para-Medical Personnel It is hoped that this publication would prove a useful reference for Government departments, private institutions, academia and researchers. -

Planning & Development Board

PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT VISION To bring the less developed areas of Punjab at par with developed areas by providing equal opportunities of employment and income generation for improving the living standard. POLICY Maintain adequate flow of development resources to backward areas of Punjab to remove regional imbalances. Targeted poverty alleviation schemes for less developed areas of Punjab. Improve delivery of public services through provision of infrastructure and other basic amenity schemes. Encouragement of private sector participation in public sector through public private partnership. Capacity building of Public Sector employees. OBJECTIVES To ameliorate and uplift the living conditions of the rural population in Barani Area & Southern Punjab. Poverty alleviation in the deprived areas of the Southern Punjab Provision of basic infrastructure in Southern Punjab. To enhance the capacity of government servants for policy making. To provide reliable data for evidence based planning. STRATEGY Pro-poor interventions through local and donor participation. Initiation of capacity building programs for Public Sector Civil Servants. Conduct Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) after every 3 years for provision of reliable data. 625 Skills development training for the poorest of the poor to uplift their income for improved livelihood. Development of Barani areas through construction of water reservoirs, solar energy solutions and afforestation for soil conservation. Provision of drinking water facility and road network for alienated Cholistanis. Betterment of accessibility through road network in tribal area of Punjab for improved economic activities and law & order situation. STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS IFAD assisted Southern Punjab Poverty Alleviation Project (SPPAP) for targeting poorest of the poor in Bahawalnagar, Bahawalpur, Muzaffargarh, D.G Khan, R.Y Khan and Rajanpur for Livelihood enhancement through assets creation and Agricultural & Livestock Development. -

Village List of Gujranwala , Pakistan

Census 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-18 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST I PUNJAB Lahore Divisiona .,.(...t..G.ElCY- OF THE PROVINCIAL TEN DENT CENSUS, JUr.8 1952 ,NO BAHAY'(ALPUR Prleo Ps. 6·8-0 FOREWORD This Village List has been pr,epared from the material collected in con" nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be avaflable and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showing its area to the nearest square mile. and Its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsil the Revenue Kanungo holqos are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo holqa and the remaining Villages comprising the ha/qas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column o. Rokhs (tree plantations) and other similar areas even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast numbers have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries. -

Planning Report Ferozwala 2008

PUNJAB MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT FUND COMPANY PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) PLANNING REPORT FEROZWALA 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Punjab Municipal Service Improvement Project (PIMSIP) ......................................................................... 1 1.2 KEY FEATURES OF PMSIP ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 PMSIP PLANNING ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3.1 Limitations of PMSIP Planning ................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 THE PLANNING PROCESS ................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4.1 Secondary Data Collection .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.4.2 Mapping ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Volume 2 BAHAWALPUR

Volume 2 BAHAWALPUR i Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Punjab 2007-08 VOLUME -2 BAHAWALPUR GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF STATISTICS MARCH 2009 Contributors to the Report: Bureau of Statistics, Government of Punjab, Planning and Development Department, Lahore UNICEF Pakistan Consultant: Manar E. Abdel-Rahman, PhD M/s Eycon Pvt. Limited: data management consultants The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey was carried out by the Bureau of Statistics, Government of Punjab, Planning and Development Department. Financial support was provided by the Government of Punjab through the Annual Development Programme and technical support by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). The final reportreport consists consists of of 36 36 volumes volumes. of whichReaders this may document refer to is the the enclosed first. Readers table may of contents refer to thefor reference.enclosed table of contents for reference. This is a household survey planned by the Planning and Development Department, Government of the Punjab, Pakistan (http://www.pndpunjab.gov.pk/page.asp?id=712). Survey tools were based on models and standards developed by the global MICS project, designed to collect information on the situation of children and women in countries around the world. Additional information on the global MICS project may be obtained from www.childinfo.org. Suggested Citation: Bureau of Statistics, Planning and Development Department, Government of the Punjab - Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, Punjab 2007–08, Lahore, Pakistan. ii MICS PUNJAB 2007-08 FOREWORD Government of the Punjab is committed to reduce poverty through sustaining high growth in all aspects of provincial economy. An abiding challenge in maintaining such growth pattern is concurrent development of capacities in planning, implementation and monitoring which requires reliable and real time data on development needs, quality and efficacy of interventions and impacts. -

Panel Hospitals

LAHORE HOSPITALS SERIAL NAME OF HOSPITAL ADDRESS TELEPHONE # NO. 1 Akram Eye Hospital Main Boulevard Defence Road Lahore. 042-36652395-96 2 CMH Hospital CMH Lahore Cantt., Lahore 042-6699111-5 3 Cavalry Hospital 44-45, Cavalry Ground Lahore Cantt. 042-36652116-8 4 Family Hospital 4-Mozang Road Lahore 042-37233915-8 5 Farooq Hospital 2 Asif Block, Main Boulevard Iqbal Town, Lahore 042-37813471-5 6 Fauji Foundation Bedian Road Lahore Cantt. 042-99220293 7 Gulab Devi Hospital Ferozepur Road Lahore 042-99230247-50 8 Ittefaq Hospital Near H. Block Model Town, Lahore 042-35881981-8 9 Masood Hospital 99, Garden Block, Garden Town, Lahore 042-35881961-3 10 Prime Care Hospital Main Boulevard Defence Lahore 042-36675123-4 11 Punjab Institute of Cardiology Jail Road Lahore. 042-99203051-8 12 Punjab Medical Centre 5, Main boulevard, Jail Road, Lahore 042-35753108-9 13 Laser Vision Eye Hospital 95-K, Model Town, Lahore 042-35868844-35869944 14 Sarwat Anwar Hospital 2, Tariq block Garden Town, Lahore 042-35869265-6 15 Shalimar Hospital Shalimar Link Road, Mughalpura Lahore 042-36817857-60, 111205205 16 Rasheed Hospital Branch 1, Main Boulevard Defence Lahore 042-336673192-33588898 Branch 2, Garden Town Lahore. 17 Orthopedic Medical Complex & Hospital Opposite Kinnarid College Jail Road, Lahore 042-37551335-7579987 18 National Hospital & Medical Centre 132/3, L-Block, LCCHS Lahore Cantt. 042-35728759-60 F: 042-35728761 19 Army Cardiac Centre Lahore Cantt. 20 Dental Aesthetics Clinic 187-Y, Block D.H.A., Lahore – Pakistan 042-35749000 21 Sana Dental Aesthetics 153-DD, CCA Phase-IV, DHA Lahore 042-37185861-2 CONSULTANTS 1 Cavalry Dental Clinic 26, Commercial Area, Cavalry Ground Lahore 042-36610321 2 Dr.