Sioux County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scroll Down for Complete Article

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Development of Cattle Raising in the Sandhills Full Citation: W D Aeschbacher, “Development of Cattle Raising in the Sandhills,” Nebraska History 28 (1947): 41-64 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1947CattleSandhills.pdf Date: 5/08/2017 Article Summary: Cattlemen created brands, overseen by stockmen’s associations, in hopes of preventing theft. Railroads attracted settlers, carried cattle to market, and delivered new breeds of stock. Scroll Down for complete article. Cataloging Information: Names: John Bratt, Bartlett Richards, E A Burnett, Thomas Lynch, R M “Bud” Moran Nebraska Place Names: Hyannis, Whitman, Ashby Keywords: brands, acid, the Spade, One Hundred and One, the Bar 7, the Figure 4, Nebraska Stock Growers Association, cattle rustling, roundups, Union Pacific, Burlington and Northern, Texas Longhorns, Shorthorns (Durhams), Hereford, Polled-Angus, John Bratt, E A Burnett Development of Cattle Raising in the Sandhills W. D. Aeschbacher One of the problems encountered by people running cattle on the open range is that of identification and estab lishment of ownership. -

Plan for the Roadside Environment - 59

Nebraska Department of Roads PLAN FOR THE ROADSIDE ENVIRONMENT - 59 - - 60 - Description – Region “D” Environmental Components • Climate ○ Plant hardiness zone - This region is primarily within Zone 4b of the USDA Plant Materials Hardiness Zone Map with a range of annual minimum temperatures between -20 to -25 degrees Fahrenheit. ○ Annual rainfall – Considered semi-arid, participation ranges from 23 inches per year in the east portion of the region to less than 17 inches in the west. • Landform – A fragile sandy rangeland of undulating fields of grass-stabilized sand dunes. Dunes generally align in a northwesterly to southeasterly direction. In the eastern edge, the dunes transition to flat sandy plains with wet meadows and marshes through Rock, Holt, and Wheeler Counties. A distinct lake area exists in the north central portion of the region where the high water table allows nearly 2,000 scattered small shallow lakes. The western end of this Sandhills region contains a second area of small scattered lakes that are moderate to highly alkaline. The alkaline lakes have limited influence from ground water and are in an area referred to as the “closed basin area” generally devoid of streams. • General soil types – Region “D” consists of sand with very little organic matter. These soils are fragile and highly susceptible to wind erosion. Water erosion is of less concern except where water is concentrated in steep ditches. Clay lenses that pond water are found in the western portion of this region. • Hydrology High infiltration rates, up to 10 feet per day, allow rainwater and snowmelt to percolate rapidly downward. -

Nebraska's Niobrara & Sandhills Safari

Nebraska’s Niobrara & Sandhills Safari With Naturalist Journeys & Caligo Ventures May 28 – June 4, 2019 866.900.1146 800.426.7781 520.558.1146 [email protected] www.naturalistjourneys.com or find us on Facebook at Naturalist Journeys, LLC Naturalist Journeys, LLC / Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 / 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com / caligo.com [email protected] / [email protected] Hidden almost in plain sight, Nebraska has a giant secret-- the spectacular Sandhills. A region with 128 million acres of Tour Highlights sand dunes mostly covered in prairie, sustained by rainfall ✓ Canoe the Niobrara Wild and Scenic and groundwater, then sliced by beautiful rivers. River (including a visit to Smith Falls), and canoe, tube, or tank the Calamus The region has a plethora of hidden treasures that will be River near our lodging the quests of your tour. We will seek out the region’s ✓ Witness herds of Bison and Elk, Black- amazing plants, wildlife, wetlands, rivers and unique tailed Prairie Dog towns, and other features. You will get to meet the conservationists and species on the native prairies at Fort ranch families who care for the rich native prairie Niobrara and Valentine National community that supports them and stabilizes about 20,000 Wildlife Refuges square miles of sand dunes. ✓ Discover the amazing Ashfall Fossil Beds that contain intact, complete We will look into the wetland eyes of the Ogallala Aquifer specimens of horses, camels, rhinos, that peek out from below the dunes, and explore its waters and other fossils in the stunning streams and waterfalls that hide in the ✓ Venture deeper into the sandhills on a valleys. -

Community Health Needs Assessment Regional West Medical Center

Community Health Needs Assessment Regional West Medical Center 2017 2017 Community Health Needs Assessment Regional West Medical Center 0 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2017 Community Health Needs Assessment Regional West Medical Center 0 Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................ 2 List of Tables ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the CEO ......................................................................................... 7 About Regional West Medical Center ..................................................................... 8 Introduction .................................................................................................. 10 MAPP Phase 1: Organize for Success/Partnership Development .................................... 12 MAPP Phase 2: Visioning ................................................................................... 13 MAPP Phase 3: Four MAPP Assessments ................................................................. 14 Community Health Status Assessment ................................................................ 15 Community Profile .................................................................................... 15 General Health Status ................................................................................ 45 Community Themes and Strengths Assessment ................................................... 107 Community Focus -

NEBRASKA STATE HISTORICAL MARKERS by COUNTY Nebraska State Historical Society 1500 R Street, Lincoln, NE 68508

NEBRASKA STATE HISTORICAL MARKERS BY COUNTY Nebraska State Historical Society 1500 R Street, Lincoln, NE 68508 Revised April 2005 This was created from the list on the Historical Society Website: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/markers/texts/index.htm County Marker Title Location number Adams Susan O. Hail Grave 3.5 miles west and 2 miles north of Kenesaw #250 Adams Crystal Lake Crystal Lake State Recreation Area, Ayr #379 Adams Naval Ammunition Depot Central Community College, 1.5 miles east of Hastings on U.S. 6 #366 Adams Kingston Cemetery U.S. 281, 2.5 miles northeast of Ayr #324 Adams The Oregon Trail U.S. 6/34, 9 miles west of Hastings #9 Antelope Ponca Trail of Tears - White Buffalo Girl U.S. 275, Neligh Cemetery #138 Antelope The Prairie States Forestry Project 1.5 miles north of Orchard #296 Antelope The Neligh Mills U.S. 275, Neligh Mills State Historic Site, Neligh #120 Boone St. Edward City park, adjacent to Nebr. 39 #398 Boone Logan Fontenelle Nebr. 14, Petersburg City Park #205 Box Butte The Sidney_Black Hills Trail Nebr. 2, 12 miles west of Hemingford. #161 Box Butte Burlington Locomotive 719 Northeast corner of 16th and Box Butte Ave., Alliance #268 Box Butte Hemingford Main Street, Hemingford #192 Box Butte Box Butte Country Jct. U.S. 385/Nebr. 87, ten miles east of Hemingford #146 Box Butte The Alliance Army Air Field Nebr. 2, Airport Road, Alliance #416 Boyd Lewis and Clark Camp Site: Sept 7, 1804 U.S. 281, 4.6 miles north of Spencer #346 Brown Lakeland Sod High School U.S. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) A United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable'. For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (IMPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property__________________________________________________ Historic name Hotel Chadron____________________________________________ Other names/site number Railroad YMCA, Qlde Main Street Inn, DW03-23_____________________ 2. Location Street & number 115 Main Street Not for publication [ ] City or town Chadron______ Vicinity [] State Nebraska Code NE County Dawes Code 045 Zip code 69337 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Sandhills Ranch Properties

Blue Creek Facts . Blue Creek Ranch is located on the southwestern edge of the Nebraska Sandhills, and is home to over 3,900 bison. The 85,635-acre ranch is mainly comprised of native sandhills rangeland with the unique feature of being divided on the southern half of the ranch by Blue Creek, a tributary of the North Platte River. Blue Creek is the dividing line between the true sandhills region of Nebraska to the north and the clay soils and hard grass prairie system to the south. Blue Creek History Blue Creek ranch was the site of “The Battle of Blue Water” the first major conflict between the U.S. Military and the Sioux Indians from 1854 to 1856. The US Military was led by General Harney and attacked a band of Sioux Indians led by Little Thunder. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.” Blue Creek is also the site of a naturally occurring spring called “Gusher Springs.” Gusher Springs is believed to be the second largest spring in Nebraska with a measured flow of 3,750 gal./min. Holistic Management 1. Profitability 2. Land Stewardship 3. Conservation Efforts 4. Community and Employees Profitability - Bison Bison Facts . Grazed using a rotational and deferred grazing system . Three grazing herds . Main herd - 1,400 breeding females - 100 breeding bulls . Stockers - 450 stocker heifers, 550 stocker bulls . Yearlings - 1,170 weaned calves . Ratio of cows to bulls is 14:1 . Bison have a 285- day gestation and birth weight of about 50 pounds . -

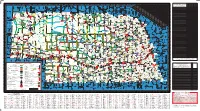

Nebraska Bicycle Map Legend 2 3 3 B 3 I N K C R 5 5 5 6 9 S55a 43 3 to Clarinda

Nebraska State Park Areas 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Park entry permits required at all State Parks, TO HOT SPRINGS TO PIERRE TO MITCHELL TO MADISON 404 402 382 59 327 389 470 369 55 274 295 268 257 96 237 366 230 417 327 176 122 397 275 409 53 343 78 394 163 358 317 Recreation Areas and State Historical Parks. 100 MI. 83 68 MI. E 23 MI. 32 MI. NC 96 113 462 115 28 73 92 415 131 107 153 151 402 187 40 212 71 162 246 296 99 236 94 418 65 366 166 343 163 85 LIA Park permits are not available at every area. Purchase 18 TO PIERRE AL E 183 47 RIC 35 446 94 126 91 48 447 146 158 215 183 434 219 56 286 37 122 278 328 12 197 12 450 74 398 108 309 119 104 from vendor at local community before entering. 105 MI. D A K O T A T TYPE OF AREA CAMPING SANITARY FACILTIES SHOWERS ELEC. HOOKUPS DUMP STATION TRAILER PADS CABINS PICNIC SHELTERS RIDES TRAIL SWIMMING BOATING BOAT RAMPS FISHING HIKING TRAILS CONCESSION HANDICAP FACILITY 73 T S O U T H A 18 E E T H D A K O T A 18 F-6 B VU 413 69 139 123 24 447 133 159 210 176 435 220 69 282 68 89 279 328 26 164 43 450 87 398 73 276 83 117 S O U 18 471 103°00' 15' 98°30' LLE 1. -

Sandhill Stats Spread of Invasives Like Red Cedar Are Causing Habitat Loss Location: North-Central Nebraska and Fragmentation Throughout the Sandhills

United States Department of Agriculture SANDHILLS PROJECT A HOSTILE TAKEOVER The Sandhills landscape of Nebraska is speckled with lakes, wetlands, wet meadows, spring-fed streams - and unfortunately - too many eastern red cedar trees. The 19,300-square-mile grass-covered sand dune formation in north-central Nebraska serves as an oasis for wildlife, including the greater prairie-chicken and American burying beetle. The Sandhills are also critically important to waterfowl, Photos by Aaron Price, USDA Price, Aaron by Photos who nest in the region. The conversion of rangelands to cultivated crops and the Sandhill Stats spread of invasives like red cedar are causing habitat loss Location: North-Central Nebraska and fragmentation throughout the Sandhills. To reverse Habitat Type: Grassland, wetlands, wet-meadows the loss and fragmentation of habitat, NRCS is working Target Species: Greater Prairie Chicken and with agricultural producers to install grazing management American Burying Beetle practices to improve rangeland health and wildlife habitat. Other Species: Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, Dicksissel, Eastern Meadowlark, Field Sparrow, Grasshopper Sparrow, Swainson’s Hawk, Monarch LANDOWNERS ARE PART OF THE SOLUTION Butterfly, Upland Sandpiper, Western Meadowlark, Sharp-tailed Grouse and Regal Fritillary Butterfly Landowners in Nebraska are helping restore the Sandhill Partners: Landowners, Sandhills Task Force, landscape by improving the health of rangelands using Nebraska Cattlemen, Rainwater Basin Joint prescribed grazing and removing invading cedar trees. Venture, Nebraska Game and Parks, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pheasants Forever Natural Resources Conservation Service Working Lands for Wildlife SANDHILLS PROJECT Through grazing management, mechanical removal and prescribed burning, producers can manage this threat to the landscape as cedar trees shade out other plants, which degrades the quality of forage for livestock and habitat for wildlife. -

July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2021 Nebraska's Panhandle

July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2021 Nebraska’s Panhandle Comprehensive Youth Services, Juvenile Justice and Violence Prevention Plan For the counties of: Banner, Box Butte, Cheyenne, Dawes, Deuel, Garden, Kimball, Morrill, Scotts Bluff, Sheridan, and Sioux Counties Chairpersons and contact information found on the following page. Facilitated and completed through collaboration of the Panhandle Partnership, Inc. Panhandle Comprehensive Youth Services, Juvenile Justice and Violence Prevention Plan 2018-2021 / Page 1 County Board Chairpersons County Chairman County Address County Phone Banner Robert 3720 Road 34 Gering 308.225.1953 Gifford NE 60341 Box Butte Mike 1512 W 3rd Street 308.760.8176 McGinnis P.O. Box 578 Alliance, NE 69301 Cheyenne Darrell J. 1104 Linden St. 308.254.3526 Johnson Sidney, NE 69162 Dawes Jake Stewart 451 Main Street 308.432.6692 Chadron NE 69337 Deuel William 16124 Rd 14 308.874.3290 Klingman Chappell, NE 69129 Garden Casper 4685 Rd 199 308.772.3924 Corfield Lewellen NE 69147 Kimball Larry 5310 Rd 52 N 308.682.5629 Engstrom Kimball NE 69145 Morrill Jeff Metz 11830 Rd 95 308.262.1351 Bayard, NE 69334 Scotts Bluff Mark 2410 4th Avenue 308.436.6600 Masterton Scottsbluff NE 69361 Sheridan Jack Andersen 1334 Gifford Ave 308.762.1784 Lakeside, NE 69351 Sioux Joshua 961 River Road 308.665.2558 Skavdahl Harrison NE 69346 Panhandle Comprehensive Youth Services, Juvenile Justice and Violence Prevention Plan 2018-2021 / Page 2 II COMMUNITY TEAM Description The Panhandle Partnership, Inc. (PPI) is the overarching collaboration for this community team. PPI was formed as a 501 (c) 3 in 1998. -

Conservation Projects in the Sandhills of Nebraska

CONSERVATION PROJECTS IN THE SANDHILLS OF NEBRASKA Chad Christiansen, USFWS Bill Vodehnal, NGPC Ashley Garrelts, STF AGENDA Overview of Sandhills Threats to Sandhills Habitat Restoration Projects Programs & Implementation SANDHILLS Largest Sand-Dune Area In Western Hemisphere Largest Grass Stabilized Dune Region In Northern Great Plains Comparison . 10 Times Larger Than State Of Delaware . 3 Times Larger Than State Of Massachusetts 19,300 SQUARE MILE REGION 265 MILES EAST TO WEST 130 MILES NORTH TO SOUTH SANDHILLS First ranches began 95% grassland in late 1800’s 11.5 million acres 90% private Ranching main ownership industry SANDHILLS HYDROLOGY Ogallala Aquifer . About 1 billion acre feet . 1.3 million acres of of groundwater wetlands . Only place exposed as . 1,500-2,000 lakes surface water SANDHILLS WILDLIFE Reptiles and Amphibians . 27 of 60 species Insect . Monarch Butterfly . American Burying Beetle Mammals . 55 of 95 species Birds . 314 of 404 species . 12 endemic to NE SANDHILLS WILDLIFE Due to its variety of both wetland and grassland habitats, it’s identified as an important geography for numerous avian species . Most significant waterfowl nesting habitat outside of Prairie Pothole region . Nesting habitat for High Plains Flock of Trumpeter Swans . Nesting habitat for ~4 million grassland birds . Sharp-tailed grouse . Greater Prairie Chicken FLAGSHIP SPECIES OF THE PRAIRIE PRAIRIE GROUSE FACTS Area sensitive species requiring large, open expanses of grasslands (75% grassland and 25 % cropland/woody) Home range -

Niobrara River Two Miles Beyond Brewer Bridge Is NEBRASKA GAME and Conner Rapids, Which You Can Hear Before WATER TRAIL PARKS COMMISSION You See

Niobrara River Two miles beyond Brewer Bridge is NEBRASKA GAME AND Conner Rapids, which you can hear before WATER TRAIL PARKS COMMISSION you see. Stay to the left, then make a sharp PO Box 30370, Lincoln, NE 68503 right turn and go directly down the middle of 402-471-0641 • www.outdoornebraska.org the river. GENERAL INFORMATION One mile farther is Fritz’s Island. Go left The Niobrara River is scenic throughout its around the island. Going to the right will take 535-mile course from its source in eastern you over a rock ledge. Wyoming and through northern Nebraska to Less than a mile farther is The Chute its mouth at the Missouri River near Niobrara. (Fritz’s Narrows). Stay in the middle for a fun But at Valentine, things are spectacular. ride through choppy water. In 1991 a 76-mile stretch of Niobrara was Another hour, about 3.5 miles down- designated as a National Scenic River deserving stream, is Rocky Ford (Class 3). Stay to the left special protection and recognition. Within this here and portage around the rapids. stretch, now managed by the National Park About two miles below Rocky Ford is Service, the river has carved its way through up Egelhoff’s Rapids (Class 2-3). Stay to the left to 300 feet of earth and below the surface of the and portage again, or you will be surprised by vast Ogallala Aquifer, the primary source of its a large hole in the middle of the river that is flows. Groundwater seeps from banks and disguised until it’s too late to stop.