The Role of Microfat Grafting in Facial Contouring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Dental Diseases in Children and Malocclusion

International Journal of Oral Science www.nature.com/ijos REVIEW ARTICLE Common dental diseases in children and malocclusion Jing Zou1, Mingmei Meng1, Clarice S Law2, Yale Rao3 and Xuedong Zhou1 Malocclusion is a worldwide dental problem that influences the affected individuals to varying degrees. Many factors contribute to the anomaly in dentition, including hereditary and environmental aspects. Dental caries, pulpal and periapical lesions, dental trauma, abnormality of development, and oral habits are most common dental diseases in children that strongly relate to malocclusion. Management of oral health in the early childhood stage is carried out in clinic work of pediatric dentistry to minimize the unwanted effect of these diseases on dentition. This article highlights these diseases and their impacts on malocclusion in sequence. Prevention, treatment, and management of these conditions are also illustrated in order to achieve successful oral health for children and adolescents, even for their adult stage. International Journal of Oral Science (2018) 10:7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-018-0012-3 INTRODUCTION anatomical characteristics of deciduous teeth. The caries pre- Malocclusion, defined as a handicapping dento-facial anomaly by valence of 5 year old children in China was 66% and the decayed, the World Health Organization, refers to abnormal occlusion and/ missing and filled teeth (dmft) index was 3.5 according to results or disturbed craniofacial relationships, which may affect esthetic of the third national oral epidemiological report.8 Further statistics appearance, function, facial harmony, and psychosocial well- indicate that 97% of these carious lesions did not receive proper being.1,2 It is one of the most common dental problems, with high treatment. -

Maxillary Osteotomies and Bone Grafts for Correction of Contoural

Maxillary Osteotomies and Bone Grafts for Correction of Contoural and Occlusal Deformities*® M. L. LEWIN, M.D. RAVELO V. ARGAMASO, M.D. ABRAHAM I. FINGEROTH, D.D.S. Bronx, New Y ork One of the major aims of modern management of the cleft palate patient is the prevention of skeletal deformity. With present day surgical management and orthodontic treatment, pronounced maxillary hypoplasia is rarely encountered. Severe hypoplasia of the entire maxillary compound is seen in other congenital malformations, as in Crouzon's disease. For some patients who have a striking disproportion between the max- illa and the mandible with pseudo prognathism, mandibular osteotomy with recession of the mandible will restore the occlusal relationship and correct the contoural deformity (Figure 1). Skeletal deformities in cleft palate patients are usually limited to the alveolar portion of the maxilla. The recession of the maxilla in such patients may often be improved by prosthetic restoration. When the upper jaw is edentulous or nearly so, a denture will establish satisfactory contour and occlusion. Occasionally, the upper suleus is deepened to accom- modate a larger labial component. A denture will not correct the deform- ity when there is hypoplasia of the entire maxillary compound. If maxil- lary hypoplasia exists without concomitant malocclusion, onlay bone grafts to the anterior facial wall will improve the facial contour (7, 8) (Figure 2). However, maxillary hypoplasia is generally associated with severe malocclusion and can only be corrected by midface osteotomy. Facial osteotomies are based on the work of LeFort who studied the mechanism of fractures of the facial skeleton. Because of the variations in the strength and fragility of various parts of the facial skeleton, fractures of the face usually follow a typical pattern. -

Enhancing the Diagnosis of Maxillary Transverse Discrepancy Through 3-D

Enhancing the diagnosis of maxillary transverse A. Lo Giudice*, R. Nucera**, V. Ronsivalle*, C. Di Grazia*, discrepancy through 3-D M. Rugeri*, V. Quinzi*** *Department of Orthodontics, School of technology and surface-to- Dentistry, University of Catania, Policlinico Universitario “Vittorio Emanuele", Catania, Italy **Department of Biomedical and Dental Sciences and Morphofunctional Imaging, surface superimposition. Section of Orthodontics, University of Messina, Policlinico Universitario “G. Martino,” Messina, Italy ***Post-Graduate School of Orthodontics, Description of the digital Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy workflow with a documented email: [email protected] case report DOI 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.03.11 Abstract and it is often associated with transversal maxillary hypoplasia. Unilateral posterior crossbite is often caused by a functional shift of the mandible towards the crossbite side and it is often Background Maxillary transverse discrepancy is often diagnosed caused by a mild bilateral maxillary constriction, which causes in childhood. The evaluation of morphological characteristics of the occlusal interference leading to a functional shift of the maxilla is crucial for appropriate treatment of this condition, however conventional diagnostic method is based on visual inspection and mandible towards the crossbite in centric occlusion [Leonardi transversal linear parameters. In this paper, we described a user- et al., 2018]. This malocclusion is often treated -

Functional Treatment of Maxillary Hypoplasia and Mandibular

Dental, Oral and Maxillofacial Research Case Series ISSN: 2633-4291 Functional treatment of maxillary hypoplasia and mandibular prognathism Ben Younes-Uzan Carine1* and Benichou Laurence2 1ODF Qualified Specialist, Former pediatric orthodontic consultation assistant at Robert Debre Hospital Paris private practice 60, cours de Vincennes, 75012 Paris, France 2ODF Qualified Specialist, Bois-Colombes private practice 4, rue Moulin Massé, 92270 Bois Colombes, France Summary This is at primary teeth stage, without any diastemas, the lower teeth are tipped lingually to try to compensate for the discrepancy. Poor development of the maxilla leads to mandibular overdevelopment in the 3 planes of space. This is genetic on the father's side (Figure 2). The insufficient growth is fully amenable to correction and increase, Lateral head-film radiography shows a skeletal class III and on a since the child is young and still has residual growth, which will result panoramic film there is a lack of room for the permanent teeth at both arches (Figures 3-9), the 15 and 25 are not visible at this stage and are in the stabilization of the results that are achieved. delayed in their mineralization. The use of functional appliances allows the maxillary teeth to receive Treatment to make up for late growth will give the adult teeth room masticatory stimuli and for the maxillary arch to develop, catching up for their future positions. with its “delay”, achieving this simultaneously along with mandibular repositioning. The second case is a 6 years 4 months old boy consulting for a mandibular prognathism (Figure 10). A functional appliance harnesses the “functions” that are characteristic of living tissue to achieve its effects. -

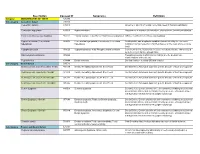

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Management of Severe Maxillary Hypoplasia with Distraction Osteogenesis in Patients with Cleft Lip and Palate Hitesh Kapadia

Management of severe maxillary hypoplasia with distraction osteogenesis in patients with cleft lip and palate Hitesh Kapadia Maxillary hypoplasia is a common finding in patients with cleft lip and palate. Clinically, this manifests as a concave profile, midface deficiency, and Class III skeletal malocclusion. Management is in accordance with the severity of the malocclusion. In the case of moderate to severe skeletal discrepancy, combined orthodontic and surgical correction is required to obtain optimal results. In most instances, definitive orthognathic surgery is pursued at skeletal maturity. In the most severe cases however, early surgical correction has been achieved with Le Fort I osteotomy and distraction osteogenesis. The technique enables successful correction of a large maxillomandibular discrepancy in a growing patient with stable results. There are also applications in a skeletally mature patient with severe maxillary deficiency. (Semin Orthod 2017; 23:314–317.) & 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. istraction osteogenesis (DO) has its origins bones. This serves to restore the periosteum and D in orthopedic surgery. The technique was allows formation of a bony callus. Using the popularized by Ilizarov in the 1940s to lengthen distraction appliance, the bone segments are long bones without the need for a graft.1 gradually pulled apart during the activation McCarthy et al.2 in 1992, was the first to report phase. This allows for formation of immature a craniofacial application in patients with bone or regenerate across the osteotomy. The congenital deformities of the mandible. It was rate of distraction is typically 1 mm per day.4 subsequently adapted to the midface and upper Once the planned position of the bone is craniofacial skeleton.3 reached, the newly formed regenerate is The goal of DO is to create new bone across an allowed to mineralize during the consolidation osteotomy site by gradually moving the two sides phase. -

EUROCAT Syndrome Guide

JRC - Central Registry european surveillance of congenital anomalies EUROCAT Syndrome Guide Definition and Coding of Syndromes Version July 2017 Revised in 2016 by Ingeborg Barisic, approved by the Coding & Classification Committee in 2017: Ester Garne, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Jorieke Bergman and Ingeborg Barisic Revised 2008 by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk and Ester Garne and discussed and approved by the Coding & Classification Committee 2008: Elisa Calzolari, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Ingeborg Barisic, Ester Garne The list of syndromes contained in the previous EUROCAT “Guide to the Coding of Eponyms and Syndromes” (Josephine Weatherall, 1979) was revised by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk, Ester Garne, Claude Stoll and Diana Wellesley at a meeting in London in November 2003. Approved by the members EUROCAT Coding & Classification Committee 2004: Ingeborg Barisic, Elisa Calzolari, Ester Garne, Annukka Ritvanen, Claude Stoll, Diana Wellesley 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Definitions 6 Coding Notes and Explanation of Guide 10 List of conditions to be coded in the syndrome field 13 List of conditions which should not be coded as syndromes 14 Syndromes – monogenic or unknown etiology Aarskog syndrome 18 Acrocephalopolysyndactyly (all types) 19 Alagille syndrome 20 Alport syndrome 21 Angelman syndrome 22 Aniridia-Wilms tumor syndrome, WAGR 23 Apert syndrome 24 Bardet-Biedl syndrome 25 Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (EMG syndrome) 26 Blepharophimosis-ptosis syndrome 28 Branchiootorenal syndrome (Melnick-Fraser syndrome) 29 CHARGE -

The Correction of Maxillary Deficiency with Internal Distraction Devices: a Multidisciplinary Approach a Alper Öz, Mete Özer, Lütfi Eroglu, Oguz Suleyman Özdemir

JCDP 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1433 Case RepoRt The Correction of Maxillary Deficiency with Internal Distraction Devices:A Multidisciplinary Approach The Correction of Maxillary Deficiency with Internal Distraction Devices: A Multidisciplinary Approach A Alper Öz, Mete Özer, Lütfi Eroglu, Oguz Suleyman Özdemir ABSTRACT craniofacial skeleton on the midface for the treatment of Aim: The purpose of this case report is to present the craniofacial deformities was first introduced by Cohen orthodontic, surgical and restorative treatments in the case of et al using a distractor device.2 an operated cleft lip and palate and severe maxillary deficiency Le Fort 1 osteotomy is a frequently performed procedure in a 14-year-old female patient. for maxillary deficiency to protract the maxilla, and some Background: Only orthodontic treatment could be inefficient studies have shown that Le Fort 1 advancement osteotomy is for cleft lip and palate patients characterized with maxillary a stable and surgically predictable procedure.3 Conventional hypoplasia. Orthodontic and surgical treatment shows sufficient results, especially with severe skeletal deficiency. orthognathic surgery techniques may not be stable in the cleft lip and palate patients due to scarring and severe deficiencies.3 Case report: A cleft lip and palate patient required complex multidisciplinary treatment to preserve health and restore However, it has been reported that maxillary advancement esthetics. Dental leveling and alignment of the maxillary and with DO in cleft palate patients is stable.4 Because of mandibular teeth were provided before the surgery. Maxillary skeletal deficiency, these patients generally exhibit poor advancement and clockwise rotation of the maxillary-mandibular complex was applied by a Le Fort 1 osteotomy with two bone formation. -

Effects of Orthognathic Surgery on Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction

Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000; 29: 183–187 Copyright C Munksgaard 2000 Printed in Denmark . All rights reserved ISSN 0901-5027 Kari Panula1, Matti Somppi2, Kaj Finne1,Kyo¨ sti Oikarinen3 Effects of orthognathic surgery 1 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Vaasa Central Hospital; 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Seina¨joki on temporomandibular joint Central Hospital; 3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Oulu, dysfunction Finland A controlled prospective 4-year follow-up study K. Panula, M. Somppi, K. Finne, K. Oikarinen: Effects of orthognathic surgery on temporomandibular joint dysfunction. A controlled prospective 4-year follow-up study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000; 29: 183–187. C Munksgaard, 2000 Abstract. A prospective follow-up study was performed to examine the influence of contemporary orthognathic treatment on signs and symptoms of TMJ dysfunction. Sixty consecutive patients were examined once preoperatively and twice postoperatively, and Helkimo’s Anamnestic and Dysfunction Indices (Ai and Di) were determined. The prevalence of headache was also assessed. The average follow-up was 4 years from the initial examination. A group of 20 patients with a similar type and grade of dentofacial deformity, who did not wish to have surgery or other occlusal therapy, served as a control group. The majority (73.3%) of the patients had signs and symptoms of TMJ dysfunction (TMD) in the initial phase. At final examination the prevalence of TMD had been reduced to 60% (P½0.013). There was a dramatic improvement in headache: initially 38 (63%) patients reported that they suffered from headache, but at the final visit only 15 (25%) did so. -

Neurological Conditions in Charaka Indriya Sthana - an Explorative Study

International Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine Review article Open Access Neurological conditions in Charaka Indriya Sthana - An explorative study Abstract Volume 13 Issue 3 - 2020 Ayurveda is a traditional Indian system of medicine and ‘Charaka samhita’ has been the Prasad Mamidi, Kshama Gupta most popular referral treatise for Ayurvedic academicians, clinicians and researchers all Dept of Kayachikitsa, SKS Ayurvedic Medical College & Hospital, over the world. ‘Indriya sthana’ is one among the 8 sections of ‘Charaka samhita’ and it India comprises of 12 chapters which deals with prognostication of life expectancy based on ‘Arishta lakshanas’ (fatal signs and symptoms which indicates imminent death). Arishta Correspondence: Prasad Mamidi, Dept of Kayachikitsa, SKS lakshanas are the fatal signs which manifests in a diseased person before death. Various Ayurvedic Medical College & Hospital, Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, neurological conditions are mentioned throughout ‘Charaka Indriya sthana’ in a scattered India, Tel 7567222856, Email way. The present study attempts to screen various references pertaining to neurological conditions of ‘Charaka Indriya sthana’ and explore their rationality, clinical significance Received: June 08, 2020 | Published: June 15, 2020 and prognostic importance in present era. Various references related to neurological conditions like, ‘Neuropathies’, ‘Neuro-ophthalmological disorders’, ‘Neurocognitive disorders’, ‘Neuromuscular disorders’, ‘Neurodegenerative disorders’, ‘Lower motor neuron syndromes’, ‘Movement disorders’ and ‘Demyelinating disorders’ are mentioned in ‘Charaka Indriya sthana’. The neurological conditions mentioned in ‘Charaka Indriya sthana’ are characterized by poor prognosis, irreversible pathology, progressive in nature and commonly found in dying patients or at the end-of-life stages. It seems that neurological conditions mentioned in ‘Charaka Indriya sthana’ have clinical applicability and prognostic significance in present era also. -

ICD-10 Dental Diagnosis Codes

ICD-10 Dental Diagnosis Codes The use of appropriate diagnosis codes is the sole responsibility of the dental provider. A69.0 NECROTIZING ULCERATIVE STOMATITIS A69.1 OTHER VINCENT'S INFECTIONS B00.2 HERPESVIRAL GINGIVOSTOMATITIS AND PHARYNGOTONSILLI B00.9 HERPESVIRAL INFECTION: UNSPECIFIED B37.0 CANDIDAL STOMATITIS B37.9 CANDIDIASIS: UNSPECIFIED C80.1 MALIGNANT (PRIMARY) NEOPLASM: UNSPECIFIED G43.909 MIGRAINE: UNSPECIFIED: NOT INTRACTABLE: WITHOUT G47.63 BRUXISM, SLEEP RELATED G89.29 OTHER CHRONIC PAIN J32.9 CHRONIC SINUSTIS: UNSPECIFIED K00.0 ANODONTIA K00.1 SUPERNUMERARY TEETH K00.2 ABNORMALITIES OF SIZE AND FORM OF TEETH K00.3 MOTTLED TEETH K00.4 DISTURBANCES OF TOOTH FORMATION K00.5 HEREDITARY DISTURBANCES IN TOOTH STRUCTURE NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED K00.6 DISTURBANCES IN TOOTH ERUPTION K00.7 TEETHING SYNDROME K00.8 OTHER SPECIFIED DISORDERS OF TOOTH DEVELOPMENT AND ERUPTION K00.9 UNSPECIFIED DISORDER OF TOOTH DEVELOPMENT AND ERUPTION K01.0 EMBEDDED TEETH K01.1 IMPACTED TEETH K02.3 ARRESTED DENTAL CARIES K02.5 DENTAL CARIES ON PIT AND FISSURE SURFACE K02.51 DENTAL CARIES ON PIT AND FISSURE SURFACE LIMITED TO ENAMEL K02.52 DENTAL CARIES ON PIT AND FISSURE SURFACE PENETRATING INTO DENTIN K02.53 DENTAL CARIES ON PIT AND FISSURE SURFACE PENETRATING INTO PULP K02.6 DENTAL CARIES ON SMOOTH SURFACE K02.61 DENTAL CARIES ON SMOOTH SURFACE LIMITED TO ENAMEL K02.62 DENTAL CARIES ON SMOOTH SURFACE PENETRATING INTO DENTIN K02.63 DENTAL CARIES ON SMOOTH SURFACE PENETRATING INTO PULP K02.7 DENTAL ROOT CARIES K02.9 UNSPECIFIED DENTAL CARIES K03.0 -

Of Human Tongue and Associated Syndromes (Review)

B )dontol - Vol 35 n° 1-2, 1992 Developmental malformations of human tongue and associated syndromes (review) E.-N. EMMANOUIL-NIKOLOUSSI, C. KERAMEOS-FOROGLOU Laboratory ofHistology-Embryology, Faculty ofMedicine, Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki (Greece). SUMMARY The development of the tongue begins as known, in the floor of the primitive oral cavity, when the human embryo is four weeks old. More specifically, the tongue develops from the région of the first three or four branchial arches during the period that the external face develops. Malformations of the tongue, are structural defects, présent at birth and happening during embryogenesis. The most common malformations are : 1. Aglossia 2. Microglossia, which is always combined with other defects and syndromes, like Moebius syndrome 3. Macroglossia, which is commonly associated with cretinism, Down’s syndrome, Hunter’s syndrome, Sanfilippo syndrome and other types of mental retardation 4. Accesory tongue 5. Long tongue 6. Cleft or Bifid tongue, condition very usual in patients with the orodigitofacial syndrome 7. Glossitis Rhombica Mediana, a developmental malformation ? 8. Lingual thyroid. Malformations are extensively analysed and discussed. KEY WORDS : Developmental - Malformations - Defects - Syndromes - Tongue RÉSUMÉ MALFORMATIONS DE LA LANGUE HUMAINE ET SYNDROMES ASSOCIES (REVUE DE LA LITTERATURE) Le développement de la langue commence au niveau du plancher de la cavité orale primitive lorsque l’embryon humain est âgé de 4 semaines. Plus précisément, la langue se développe dans la région des trois ou quatre premiers arcs branchiaux durant la période du développement de la face externe. Les malformations de la langue correspondent à des défauts de structure présents à la naissance et survenant au cours de l’embryogenèse.