Practical Building Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final-Portafolio-2017.Pdf

ó Pacific Curbing is the leading company for Pinellas & Hillsborough area decorative concrete landscape curbing. Our decorative, stamped curbing is on the cutting edge of landscape design. 11/11/2016 2 ó Concrete curbing is a professionally installed, permanent, attractive concrete border edging that provides great additions and solutions to any landscape and serves as a weed and grass barrier by outlining flowerbeds. Pacific Curbing decorative concrete curbing can be installed around trees, flowerbeds, sidewalks and just about anywhere you like. 11/11/2016 3 ó Concrete curbing can enhance your landscape, it is the half of price of bricks and is a permanent solution, increase curb appeal, decrease the time spent trimming around landscape beds and increase your property value. 11/11/2016 4 ó Rollers are a soft textures impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó You can choose a natural looking like stone or you can choose something symetrical. ó Price per foot $5.75 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. ó PSI 3600 Ashlar Basketweave Brick Bone Cobblestone Flagstone H Brick Herringbone Offset bond Old stone Pebblestone Random Riverstone Running bond L Running bond Slate Spanish Texture Treebark Wood RAMDOM ROLLER RUNNING BOND ROLLER SLATE ROLLER FLAGSTONE ROLLER SPANISH TEXTURE SINGLE BRICK ó Stamps are deep impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó They come on a symetrical designs. ó Price per foot $6 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. -

Fortifications and Town Planning in Kyrrhos: Its Hellenistic Origin and Its Evolution Jeanine Abdul Massih, Mathilde Gelin

Fortifications and town planning in Kyrrhos: its Hellenistic origin and its evolution Jeanine Abdul Massih, Mathilde Gelin To cite this version: Jeanine Abdul Massih, Mathilde Gelin. Fortifications and town planning in Kyrrhos: its Hellenistic origin and its evolution. Rune Frederiksen; Silke Müth; Peter I.Schneider; Mike Schnelle. Focus on fortifications. New Research on Fortifications in the Ancient Mediterranean and the NearEast, Oxbow Books, pp.207-219, 2016, Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, 978-1-78570-131-3. hal-03025892 HAL Id: hal-03025892 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03025892 Submitted on 1 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License FOCUS ON FOCUS ON FORTIFICATIONS New Research on Fortifications in the Ancient Mediterranean and the Near East AN OFFPRINT FROM Fokus Fortifikation Studies: Volume 2 FOCUS ON FORTIFICATIONS New Research on Fortifications in the Ancient Mediterranean and the Near East edited by Rune Frederiksen, Silke Müth, Peter I. Schneider and Mike Schnelle Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-131-3 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-132-0 Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, Volume 18 © Oxbow Books 2016 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by OXBOW BOOKS 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083 Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, no. -

The Elegance of Simplicity. the Elegance of Simplicity

The elegance of simplicity. g{x ÑÉãxÜ Éy |ÇzxÇ|Éâá wxá|zÇA The durability of concrete. Continuous concrete borders to enhance any landscape design. Other Services Sealant Re-spraying: The Cement Shop Curbing Company can return annually by appointment to re-spray your curbing with a powerful sealant designed to protect its surface and boost glossiness. Continuous Walkways: Ask us about beautifying your property with a continuous-pour concrete pathway. The Cement Shop Curbing Company can create permanent and customizable sidewalks in many unique styles The elegance of simplicity. without the use of concrete forms. Most importantly, the solid pour g{x ÑÉãxÜ Éy |ÇzxÇ|Éâá wxá|zÇA combats the effects of shifting and Your property is your showpiece; The durability of concrete. prevents bothersome weed and a reflection of your distinctive style and moss penetration. a shining example of pride of owner- New Bed Preparation: Looking to ship. Enhance the natural beauty and unique features of your landscape, or add a flower bed to your prop- accent an idyllic outdoor living space erty? The Cement Shop Curbing with continuous concrete curbing from Company’s specialized sod-cutting The Cement Shop Curbing Company. equipment can eliminate for you the hassle of creating new beds manually. Our precision sod- cutter can quickly and gently remove re-usable strips of sod, enabling you to add a whole new 7 Frigate Bay bed to your property without Winnipeg, MB R3X 2E9 having to dig. T: 204.295.4768 [email protected] www.cementshop.ca Contact us today for a professional, no-obligation consultation. -

Phoenician and Greek Ashlar Construction Techniques at Tel Dor, Israel

Phoenician and Greek Ashlar Construction Techniques at Tel Dor, Israel Ilan Sharon Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 267. (Aug., 1987), pp. 21-42. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-097X%28198708%290%3A267%3C21%3APAGACT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research is currently published by The American Schools of Oriental Research. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/asor.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Loose Lay Luxury Vinyl Plank & Tile Installation Guide I

MILLIKEN LVT INSTALLATION GUIDE Date: 05/2018 LOOSE LAY LUXURY VINYL PLANK & TILE INSTALLATION GUIDE I All instructions and recommendations in this guide are based on the most recent information and installation techniques available, please follow this guide to ensure a trouble free and warranty supported installation. Always check millikenfloors.com for latest installation, warranty and maintenance guides. It is the responsibility of the installer to ensure that the most current documents are used during installation. Contact Milliken Technical support if there are any specific concerns or questions prior to installation Product Handling and Site Conditions 1. Check batch and product details and quantity are correct and match purchase order. 2. Store cartons of tile and/or plank with cartons stacked one on top of the other. Do not store on end or sides, or allow cartons to bend during storage or transportation. 3. Acclimate product to job site conditions by delivering all materials, including adhesives and maintenance products, to the job site at least 48 hours prior to installation. Store all products at 65° to 85° Fahrenheit (18° to 29° Celsius) for 48 hours prior to installation. 4. The space where flooring is to be installed shall be fully enclosed and the permanent HVAC system shall be operational prior to installing flooring. The temperature shall be 65° to 85° Fahrenheit (18° to 29° Celsius) for 48 hours before installation, during installation and for 48 hours after installation. The temperature of the space shall be kept at a minimum of 50° Fahrenheit (10° Celsius) continually after installation. 5. loose lay vinyl floors should be protected from direct sunlight and not exposed to intense direct sunlight for extended periods of time. -

Stone Setting Practiced by the Masons of the Naumburg and Meissen Cathedrals— a Comparative Look at Stone Setting Techniques1

Stone Setting Practiced by the Masons of the Naumburg and Meissen Cathedrals— a Comparative Look at Stone Setting Techniques1 Katja Schröck If one aims to take a closer look at a medieval building site, it is inevitable to pay careful attention to the traces that were left on the stones set and built. This article presents a detailed study of the stone setting techniques applied during the construction of the Naumburg west choir and a comparison with the techniques applied by the masons who built Meissen Cathedral. The question of how building stones were moved to their final positions is of particular relevance, specifically as the solution of the logistic and technical challenges, which were connected with it, and the available machines were of major importance for the realisation of a construction project of this dimension. For this reason it is necessary to clarify the details of the various setting techniques that were used on the building site. The basic categories here are vertical transport and horizontal transport. It was above all the physical power of the workers that was decisive for the horizontal movement not only of the stones but also of all other building materials across the building site, using e.g. barrows or baskets. What is even more interesting is the vertical movement of the stones since it was far more complex in terms of organisation and the available technology. It was only by vertical movement that the building stones were hoisted into place. Tools were used to move the stones, e.g. so-called lifting gears and fastening means. -

PROLINESTAMPS.COM Since 1990, Proline Decorative Concrete Systems Has Been a Leader and Innovator in the Decorative Concrete Industry

PROLINESTAMPS.COM Since 1990, Proline Decorative Concrete Systems has been a leader and innovator in the decorative concrete industry. We devote our knowledge, experience, and passion to manufacturing the most durable and highest quality products, stamps, and tools on the market. Our products are designed to beautify, transform, color, restore, repair, and protect. Our comprehensive product line encompasses Concrete Stamps, Concrete Stamping Tools, Table Molds, Edge and Form liners, Pre-Cast GFRC Material, Color Hardener, Integral Color, Antique Release Powder, Liquid Release Agent, Acid Stain, Solid and Transparent Water-Based Stains, Crack and Joint Repair, Cementitious Resurfacers and Overlays, 100% Solids, Water-Based, and Metallic Epoxies, Polyurethanes, Polyaspartic, and Water-Based and Solvent-Based Sealers. Proline Decorative Concrete Systems is recognized world wide for our amazing collection of concrete stamps. We have hundreds of concrete stamp designs that offer a wide variety of textures, patterns, and specialty accent pieces. We can also create custom stamps in just about every size and shape. Our stamps are lighter, stronger, and more durable than any other concrete stamps in the industry. And our newest Magnetic Seamless Pattern Stamps are changing the future of stamped concrete forever. Proline Decorative Concrete System's stamps and products are distributed exclusively through building material supply stores and international distributors. TABLE OF CONTENTS WORLDS LARGEST SELECTION OF CONCRETE STAMPING TOOLS www.prolinestamps.com Feature Image MD7130 BW1696 02 03 MAGNETIC SEAMLESS PATTERN STAMPS OUR NEW PATENTED INNOVATIVE STAMP SYSTEM Known to the industry as the “Game Changer”, the SPS system is the culmination of studying and developing for the decorative concrete industry for over 30 years. -

Chapter 16 – Table of Contents

Bridge Maintenance Course Series Reference Manual Chapter 16 – Table of Contents Chapter 16 - Masonry Bridges ................................................................................................ 16-1 16.1 Common Types of Masonry Bridges and Masonry Bridge Elements ................................ 16-1 16.1.1 Arches ...................................................................................................................... 16-1 16.1.1.1 Coursed Ashlar Masonry ................................................................................................ 16-1 16.1.1.2 Random Ashlar Masonry ................................................................................................ 16-1 16.1.1.3 Rubble Masonry ............................................................................................................. 16-2 16.1.1.4 Arch Elements ................................................................................................................ 16-2 16.1.2 Masonry Slab Bridges .............................................................................................. 16-4 16.1.3 Substructure Elements ............................................................................................ 16-5 16.1.4 Brick, Stone and Mortar Characteristics .................................................................. 16-6 16.1.5 Architectural Veneer ............................................................................................. 16-10 16.2 Preventative and Basic Maintenance of Masonry Bridges -

Snecked Stonemasonry

Snecked stoneMASONRY by Bobby Watt This method of bonding stonework is so prevalent in Scotland and SNECKED MASONRY involves three kinds of stones: Ireland it has been referred to in some journals as ‘Celtic Bond’. Amongst the French speakers in Canada it is known as ‘travail RISERS—Or JUMPERS, these are the stones extend up through the ecossais'. horizontal beds. They can be square, or almost square, or up to three times as long as they are high. Whatever it’s called, this is a method of building an incredibly strong masonry wall with differently sized, (and even very loosely LEVELLERS—These form the bulk of the wall. They are usually at squared), stones, in either ashlar or rubble work, with a pattern that least twice as long and up to five times as long as they are high. is both handsome and, at the higher levels of workmanship, artistic. SNECKS—These are the smaller pieces that enable the mason to The principal characteristic of snecked work is the keying together make up the differential in height between the top surfaces of the of parallel courses of stone. This is achieved by interrupting the levelers and the risers. level height of a horizontal course by placing a taller stone that reaches up into the next course. This vertical interlacing gives a wall The easiest way to build snecked masonry is to work with uniform a tensile strength that enhances its compressive strength. material such as that provided by free-stone suppliers, like Indiana Limestone, who saw the stone into standard bed heights that When I served my apprenticeship we were never provided with enable us to conveniently build snecked work with a minimum of a set of instructions to build snecked work; it was picked up bother. -

• Natural Stone Veneers •

• Natural Stone Veneers • West Coast Fieldstone Experiencing Maintaining the Pangaea® Difference a Healthy Planet Beautifying your local community with products We do our part by being a good steward of that work in harmony with their natural our environment and utilizing state-of-the-art surroundings. Creating products that are technology in energy and recycling methods. intelligently designed and uniquely packaged to make the most out of your experience. 2 For more information visit www.instoneco.com Enriching our Communities We are dedicated to creating opportunities for children in developing countries through education and improved facilities. 3 West Coast Fieldstone 4 Natural Stone Quarry, Ongole, India From the Ground Up From The Ground Up not only implies that we quarry and fabricate natural stone but also deliver superior and ethical products to the professional building industry. The creation of our products have been and continue to be influenced by our customers for our customers. Since 2005, our attention to detail in product design has been a result of years of focus groups and industry feedback. We have been evolving our products and programs by listening and fulfilling our customers expectations. What works for our customers works for us! We not only specialize in natural stone quarrying and fabrication but also in building and maintaining strong relationships with our distributors and dealer networks. Our network partners ensure your products are delivered on time and on budget. We pride ourselves in the relationships we have built over the years which have enabled us to provide you with the highest quality of products and services you deserve. -

Ashlars - Rough, Smooth - Story of a Stone

ASHLARS - ROUGH, SMOOTH - STORY OF A STONE By Bro J. Fairbairn Smith An eminent sculptor was once asked: "How do you carve such beautiful statues?" He replies, "It is the simplest thing in the world. I take a hammer and chisel and from a massive, shapeless rock, I knock off all the stone I do not want, and there is the statue. It was there all the time." In every Masonic Lodge room there is, or should be, the Rough Ashlar and the Perfect Ashlar. What is their significance? What do they have to do with Masonry? In our ritual work we are taught that the Rough Ashlar "is a stone as taken from the quarry in its rude and natural state" The Rough Ashlar was not a stone that was merely picked up somewhere. It was a stone that has been selected. Some work was done upon it. It was apparently a good stone. It was a stone that showed good prospects of being capable of being made into a Perfect Ashlar. If it had not been a good stone, it would never have been cut out from the quarry. So it is with our prospective member. He cannot be merely picked up somewhere. He must be selected. Before he is ready to be initiated some work must be done upon him. He must stand certain basic tests. He must be apparently of good material. He must be a man who shows good prospects of being capable of being made into a good Mason. If he had not been a good man, he should never have been proposed for membership. -

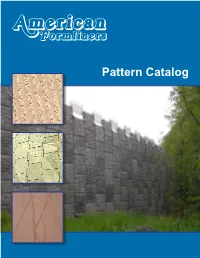

Pattern Catalog More Patterns

Pattern Catalog More Patterns... Call 877-533-5842 More Possibilities! Table of Contents More Patterns... More Possibilities! ....................................................................................................1 Application ..........................................................................................................................................2 Pattern Index ......................................................................................................................................3 Trapezoid Patterns .............................................................................................................................4 Stone Patterns .................................................................................................................................. 11 Wood Patterns ..................................................................................................................................18 Fractured Patterns ............................................................................................................................21 Masonry Patterns .............................................................................................................................25 Other Patterns ..................................................................................................................................30 Technical Data ..................................................................................................................................31 Warranty