The Late Medieval Church at Wensley, North Yorkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire Wenham, Leslie P. How to cite: Wenham, Leslie P. (1946) A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HISTORY OP RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIREc i. To all those scholars, teachers, henefactors and governors who, by their loyalty, patiemce, generosity and care, have fostered the learning, promoted the welfare and built up the traditions of R. S. Y. this work is dedicated. iio A HISTORY OF RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIRE Leslie Po Wenham, M.A., MoLitt„ (late Scholar of University College, Durham) Ill, SCHOOL PRAYER. We give Thee most hiomble and hearty thanks, 0 most merciful Father, for our Founders, Governors and Benefactors, by whose benefit this school is brought up to Godliness and good learning: humbly beseeching Thee that we may answer the good intent of our Founders, "become profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth, and at last be partakers of the Glories of the Resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Yorkshire Painted and Described

Yorkshire Painted And Described Gordon Home Project Gutenberg's Yorkshire Painted And Described, by Gordon Home This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Yorkshire Painted And Described Author: Gordon Home Release Date: August 13, 2004 [EBook #9973] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Michael Lockey and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger YORKSHIRE PAINTED AND DESCRIBED BY GORDON HOME Contents CHAPTER I ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY CHAPTER II ALONG THE ESK VALLEY CHAPTER III THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR CHAPTER IV THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER V Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER VI WHITBY CHAPTER VII THE CLEVELAND HILLS CHAPTER VIII GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY CHAPTER IX FROM PICKERING TO RIEVAULX ABBEY CHAPTER X DESCRIBES THE DALE COUNTRY AS A WHOLE CHAPTER XI RICHMOND CHAPTER XII SWALEDALE CHAPTER XIII WENSLEYDALE CHAPTER XIV RIPON AND FOUNTAINS ABBEY CHAPTER XV KNARESBOROUGH AND HARROGATE CHAPTER XVI WHARFEDALE CHAPTER XVII SKIPTON, MALHAM AND GORDALE CHAPTER XVIII SETTLE AND THE INGLETON FELLS CHAPTER XIX CONCERNING THE WOLDS CHAPTER XX FROM FILEY TO SPURN HEAD CHAPTER XXI BEVERLEY CHAPTER XXII ALONG THE HUMBER CHAPTER XXIII THE DERWENT AND THE HOWARDIAN HILLS CHAPTER XXIV A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE CITY OF YORK CHAPTER XXV THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICT INDEX List of Illustrations 1. -

Bolton Castle & Redmire Village

Follow in Turner’s footsteps to the spectacular... Bolton Castle & Redmire Village This short easy-going walk will take you to the historical Bolton Castle. You can see the castle much as Turner Castle did when he visited in July 1816 during his extensive Bolton ane tour of Yorkshire to sketch views for Whitaker’s A East L General History of the County of York series. Bolton Castle Bolton Arms Bolton Castle © Si Homfray Castle Bolton Redmire To Carperby A p e M d i a l l l L e a n Key B e Route e Mill Farm c Woodland k R Turner’s i Viewpoint v e Turner’s Bench r U Parking r e Public House Redmire Force Church Discover the landscapes that inspired one of Britain’s greatest artists Railway yorkshire.com/turner Follow in Turner’s footsteps to the spectacular... To start this Turner Trail... Bolton Castle & Redmire Village 01 From Redmire village hall, walk over the green and up the hill with the Bolton Arms on your left. Go under the railway bridge and turn This short easy-going walk will take you to the historical Bolton Castle. left onto the footpath and cross the bridge over Apedale Beck. You can see the castle much as Turner did when he visited in July 1816 Walk up the meadows passing a tree growing through the middle during his extensive tour of Yorkshire to sketch views for Whitaker’s A of an old barn to reach Castle Bolton Village. General History of the County of York series. -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

The Myth Of'richmond's Little Drummer Boy', Could It Be That Lewis Carroll Came up with the Idea of 'Alice's Adventures Un

The Myth of ‘Richmond’s Little Drummer Boy’, Could it be that Lewis Carroll came up with the idea of 'Alice's Adventures Underground' from hearing about 'The Legend of the 'Drummer Boy'? Around forty years prior to Lewis Carroll moving to Richmond, North Yorkshire, legend has it that a little drummer boy was lowered underground into a dark deep tunnel that supposedly linked Richmond Castle and Easby Abbey. As a child Lewis grew up with the legend of the 'Drummer Boy', consequently the book he first wrote was originally called, 'Alice's Adventures Underground' before it was renamed 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland' © The above picture is the copyright of Green Howards Museum RICHMOND North Riding of Yorkshire Legend has it there used to be a tunnel connecting Easby Abbey to Richmond Castle. After many hundreds of years, the tunnel was rediscovered at the castle, but had been quite damaged over the passing of time; only a small boy could pass through the fallen rubble. A very brave drummer boy volunteered to follow the tunnel and beat his drum as he went, so that the soldiers above could hear him and follow the path of the tunnel to Easby, thereby discovering the Abbey entrance. Half way between the Castle and the Abbey, the drumming came to an abrupt stop, and the brave little soldier was never seen again. Myth has it that the rhythm of the boys drumming sent shivers through the souls of the brave soldiers who followed the beat above. What was of more interest to the Little Drummer Boy was what lay ahead, had the drumming awoken something in the depths below, every hair on the little Drummer Boy’s body tingled electrified by fear, he knew there was something ahead he felt it in every bone in his body, he was only a little boy, but he had the courage of a Lion he continued onward till he came to yet another cavern. -

Apedale and Mproduce Seeds in Woody Cones but Yew Trees Do It Differently

6 The Northern Echo Thursday, December 3, 2009 7DAYS northernecho.co.uk COUNTRY DIARY WALKS OST members of the Christmas tree family – the conifers – Apedale and Mproduce seeds in woody cones but yew trees do it differently. Their seeds are carried singly in fleshy pink By cups that are a ripe now, although thrushes will have already eaten many Mark Reid of them. Yew foliage and its seeds are Castle lethally poisonous to mammals, but the Bolton soft pink tissue that surrounds the hard POINTS OF INTEREST seeds contains no toxins and they pass HE village of Castle quickly and safely through a bird’s gut, and so are dispersed far and wide. Bolton, with its old stone No country churchyard is complete cottages lining the green, without yew trees. They’ve been Tis completely dwarfed by associated with sacred ground for the majestic Bolton Based on Ordnance Survey mapping © centuries, although opinions are Castle. The castle was built in divided as to exactly why this might be. 1399 by Richard le Scrope, the Crown copyright:AM26/09 Some say that it has nothing to do with Chancellor of England to Richard Christianity and that they were originally II. Its walls are nine feet thick and associated with sites of pagan worship, stand 130 feet wide by 180 feet which were later taken over by early long, with four massive corner Christians. Perhaps the ancient gnarled towers nearly 100 feet high appearance of venerable yews became enclosing a central courtyard. associated with the idea of immortality. The stone for the castle came There are many well authenticated from quarries in Apedale and records of 700 year-old trees and it’s local legend also tells us that probable that they can live for two these early builders used ox blood millennia, so there’s probably no better mixed with the mortar to give it symbol of long-life in the British added strength. -

1453 Goat Yorkshire Brochure 2018 FINAL.Indd

TOURS 2018 - 2019 Day Tours from York Whitby North York Moors The Yorkshire Dales Castle Howard The Lake District 01904 405341 www.mountain-goat.com1 Welcome to Yorkshire 1972 Established Small group Get off the in 1972 experience beaten track I’d like to experience... Scheduled Tours Castles & Castles & Abbeys Coast Dales Moors Lakes & Mountains The North York Moors & Whitby Page 4 The Yorkshire Dales Page 6 Whitby, Robin Hoods Bay & The Moors Page 10 The North York Moors & Castle Howard Page 11 The Bronte’s Parsonage & Page 12 Historic Yorkshire Lake District Page 13 Useful information, pick ups & T&Cs Page 14 2 Book Online at www.mountain-goat.com Welcome to Yorkshire You book, 48 hour Friendly you go cancellation policy driver guide I’m available on... Scheduled Tours Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday ✹ ✹ ✹ ✹ The North York Moors & Whitby Page 4 ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ Page 6 ✹ ✹ ✹ ✹ ✹ The Yorkshire Dales ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ Whitby, Robin Hoods Bay & The Moors Page 10 ✹ ✹ The North York Moors & Castle Howard Page 11 ✹ The Bronte’s Parsonage & Page 12 Historic Yorkshire ✹ Lake District Page 13 ✹ Summer Tours: Winter Tours: Useful information, pick ups & T&Cs Page 14 ✹24th March 2018 ❉ 29th October 2018 – 28th October 2018 – 22nd March 2019 +44 (0)1904 405341 3 TOP SELLER North York Moors and Whitby Mondays, Thursdays, Fridays & Sundays ✹ Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays & Sundays ❉ Whitby Tour Highlights - to tick off your list! > Explore the North York Moors; one of the most stunning and historic landscapes in Britain. Discover its role in the history of England including religion, farming & mining. > Travel back in time as we head through villages established in Saxon and Viking times. -

CASTLE BOLTON an Introduction to the Built Heritage of the Village

CASTLE BOLTON An introduction to the built heritage of the village Castle Bolton is one of several Wensleydale villages which still dominates the whole area. The humble with echoes of ‘Estate Tudor’, evidence of a that take advantage of the type of site that geology parish church, still a relatively unaltered medieval campaign of improvement in the 1840s or 1850s. and landscape combined have produced on the building - crouches literally in the shadow of As usual on this side of Wensleydale, all the houses north side of the valley. It lies on a broad and the castle. on the south of the green turn their backs to it to quite level terrace sitting above a scarp and so appreciate both sun and the views southwards. commands extensive views to the south. The To the east of castle and church the village is Although ‘view’ as a component of modern house village is completely subordinate to the magnificent spread out around a long and quite wide green, names is very common throughout the area, here 14th-century palace fortress of the Scrope family, and is made up of houses of relatively humble it is virtually ubiquitous. The simple theme is status. It is thought to have been laid out at the continued by the absolutely plain and utilitarian same time as the castle was built, replacing two late 18th- or early 19th-century Methodist Chapel, earlier settlements, East and West Bolton, but if barely distinguishable from a cottage, and now, like this was the case, there is a three-century gap so many more, disused and scheduled for domestic between this date and the earliest visible structures. -

1 Henry 4 Closes in July 1403

Reigned 1399–1413. The play opens in June 1402; 1 henry 4 closes in July 1403. Written about 1597. Dramatis Personae: King Henry the Fourth Henry, Prince of Wales, called Prince Hal Prince John of Lancaster Earl of Westmoreland Sir Walter Blunt Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland Henry Percy, called Hotspur Edmund Mortimer Richard Scroop Archibald, Earl of Douglas Owen Glendower Sir Richard Vernon Sir John Falstaff Sir Michael Poins Gadshill Peto Bardolph Lady Percy, wife of Hotspur Lady Mortimer Mistress Quickly Lords, Officers, Sheriff, Vintner Chamberlain, Drawers, Carriers, Travelers and Attendants Robin Williams • www.iReadShakespeare.org • www.InternationalShakespeare.center Reigned 1399-1413. The play opens in June 1402; 1 henry 4 closes in July 1403. Written about 1597. Name and title Birth date Death date Age in play Age at death King Henry IV 1367 1413 36/37 46 Son of John of Gaunt; cousin to Richard II. Usurped Richard II and became Henry IV. Henry, Prince of Wales, called Prince Hal sep 1387 1442 of 16/17 35 Also called Henry of Monmouth. Oldest son to King Henry dystentery in IV. Mother is Mary de Bohun. France Prince John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford 1389 Sep 1435 13/14 46 3rd son of Henry IV; brother to Henry V and Gloucester; uncle to Henry VI. Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmoreland 1364 1425 38/39 61 This is Ralph, 6th Baron Neville of Raby, son of John 5th Baron and Maud Percy. Married second Joan Beaufort, daughter of Gaunt and Swynford. Sir Walter Blunt 1350 1403 52/53 53 Famous soldier and supporter of John of Gaunt. -

Bolton Castle the Historic Heart of Wensleydale

Bolton Castle Monday Sept 18th – Friday 22nd (10.00-5.30) Sunday Sept 3rd (4.00-5.30) – Wed 6th (10.00–5.30) Tues Sept 12th – Friday 15th (10.00–5.30) Making History Wild Dales Photography Painting the Dales The Historic Heart of Wensleydale Bolton Castle’s stunning setting and 600 years of history attract thousands of visitors every year to see vivid evidence of the events which have shaped it since it was built in 1399. Now there is even more to enjoy, with a new range of courses and performances based in the Castle and on its estates. Develop your skills and learn new ones in Writing, Painting, Photography, Music, Flower Arranging or Fishing – or more than one! Work independently and in groups with our inspiring course leaders. Meet new friends, enjoy exclusive access to Bolton Castle ‘out of hours’, and explore the landscape and wildlife of A 5 day practical course in writing historical A 3 day course (with Sunday induction 4.00-5.30pm) A 4 day course with Piers Browne, the distinguished Wensleydale and beyond. fiction, with guidance from tutors including with Wild Dales photographer Simon Phillpotts. Wensleydale artist and ‘Painter of the North’, Alison Weir, who has sold nearly 3 million copies Simon’s images are frequently Highly Commended reaping the benefit of his unrivalled intimate • All events and courses open to visitors and local of historical fiction and history world-wide, and in the British Wildlife Photography Awards, and knowledge of the Dales’ landscape. With 101 residents. Anthony Quinn. His novel Disappeared was chosen have featured in the Telegraph, Times, Guardian shows worldwide (35 in London galleries), 25 Royal • Residential options available on some courses. -

Great Days out a Collection of Yorkshire’S Finest Attractions

FREE2017 GUIDE! Great Days Out A collection of Yorkshire’s finest attractions www.castlesandgardens.co.uk “Bringing you a whole host of ideas for great days out for all the family with our fantastic selection of formidable castles, splendid stately homes, ancient abbeys and glorious gardens.” Front cover: The Bowes Museum Beningbrough Hall, Gallery & Gardens Welcome to Yorkshire’s Great Houses, Castles & Gardens Inspiration and fun for all the family, our ‘Great Days Out’ guide presents Yorkshire’s finest collection of attractions. Read on to find out further information about each attraction, including what’s new for 2017, directions and opening times. And with a whole series of events taking place throughout the year, there is even more reason to get out and about. From plant fairs, car and steam rallies and period re-enactments to outdoor theatre, concerts and festivals there is something for everyone. To discover even more about all of the attractions in our collection, download a range of special offers, such as 2-4-1 entry, and find ideas for days out and things to do during 2017, visit www.castlesandgardens.co.uk. Bolton Abbey 03 Getting around Yorkshire Symbols Once you’re in Yorkshire there are plenty of options for getting around, whether you prefer your own pedal National Trust property power, sitting back on a train or bus or exploring scenic back roads by car. By Bicycle English Heritage property Following on from the huge success of the magnificent Tour De France and annual Tour De Yorkshire, cycling has never been so popular. Quiet country roads, byways and a network of cycle paths, there’s a lot to see and do, so get on your bike and Yorkshire In Bloom Attractions discover Yorkshire from your saddle. -

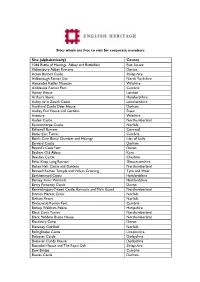

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and