Three Seventeenth-Century Rectors of Euston and a Verse in the Parish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 Row Heath

ROW HEATH ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2021 This Division comprises The Rows Ward in its entirety plus parts of Lakenheath, Kentford & Moulton, Manor and Risby Wards www.suffolkobservatory.info 2 © Crown copyright and database rights 2021 Ordnance Survey 100023395 CONTENTS ▪ Demographic Profile: Age & Ethnicity ▪ Economy and Labour Market ▪ Schools & NEET ▪ Index of Multiple Deprivation ▪ Health ▪ Crime & Community Safety ▪ Additional Information ▪ Data Sources ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILES: AN INTRODUCTION These profiles have been produced to support elected members, constituents and other interested parties in understanding the demographic, economic, social and educational profile of their neighbourhoods. We have used the latest data available at the time of publication. Much more data is available from national and local sources than is captured here, but it is hoped that the profile will be a useful starting point for discussion, where local knowledge and experience can be used to flesh out and illuminate the information presented here. The profile can be used to help look at some fundamental questions e.g. • Does the age profile of the population match or differ from the national profile? • Is there evidence of the ageing profile of the county in all the wards in the Division or just some? • How diverse is the community in terms of ethnicity? • What is the impact of deprivation on families and residents? • Does there seem to be a link between deprivation and school performance? • What is the breakdown of employment sectors in the area? • Is it a relatively healthy area compared to the rest of the district or county? • What sort of crime is prevalent in the community? A vast amount of additional data is available on the Suffolk Observatory www.suffolkobservatory.info The Suffolk Observatory is a free online resource that contains all Suffolk’s vital statistics; it is the one-stop-shop for information and intelligence about Suffolk. -

WSC Planning Applications 14/19

LIST 14 5 April 2019 Applications Registered between 1st and 5th April 2019 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/18/1567/FUL Planning Application - 2no dwellings AWA Site VALID DATE: Church Meadow 22.03.2019 APPLICANT: Mr David Crossley Barton Mills IP28 6AR EXPIRY DATE: 17.05.2019 CASE OFFICER: Kerri Cooper GRID REF: WARD: Manor 571626 274035 PARISH: Barton Mills DC/19/0502/HH Householder Planning Application - Two 10 St Peters Place VALID DATE: storey rear extenstion (following demolition Brandon 03.04.2019 of existing rear single storey extension) IP27 0JH EXPIRY DATE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs G J Parkinson 29.05.2019 GRID REF: AGENT: Mr Paul Grisbrook - P Grisbrook 577626 285941 WARD: Brandon West Building Design Services PARISH: Brandon CASE OFFICER: Olivia Luckhurst DC/19/0317/FUL Planning Application - 1no. dwelling -

CS86 Brandonанаthetfordанаbury St Edmunds

CS86 Brandon Thetford Bury St Edmunds Monday Saturday 86 86 86 86 86 86 86 86 86 86 86 NS NSch Sch NS NS Brandon, Green Road 0630 0737 0730 0942 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1542 ~ Brandon, Rattlers Road 0633 0740 0733 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 1545 1634 Brandon, Tesco Bus Stop 0635 0742 0735 0946 1046 1146 1246 1346 1446 1546 1636 Brandon, Crown Street, Mile 0638 0745 0738 0950 1050 1150 1250 1350 1450 1550 1638 End Brandon, Crown Street, Pond 0640 0746 0740 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1552 1640 Lane Brandon, St Peter's Approach 0642 0748 0742 0954 1054 1154 1254 1354 1454 1554 1642 Brandon, London Road Bus 0646 0752 0746 0958 1058 1158 1258 1358 1458 1558 1646 Shelter Brandon, Thetford Road Bus 0652 0755 0752 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1650 Shelter Thetford, Bus Interchange 0705 | | 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1615 1715 Stand C Thetford, Bury Road, 0710 via via 1020 1120 1220 1320 1420 1520 1620 1720 Queensway Barnham, Bus Shelter 0716 Elveden Elveden 1026 1126 1226 1326 1426 1526 1626 1726 Ingham, Crossroads 0725 | | 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1635 1735 Fornham St Genevieve, opp. 0729 0819 0819 1039 1139 1239 1339 1439 1539 1639 1739 Oak Close Fornham St Martin, opp. The 0730 0820 0820 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1640 1740 Woolpack Bury St Edmunds, Tollgate 0732 0822 | 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1542 1642 1742 Lane Bury St Edmunds, St | | 0830 | | | | | | | | Benedict's Upper Bury St Edmunds, West | | 0845 | | | | | | | | Suffolk College Layby Bury St Edmunds, Station Hill 0735 0825 | 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 1545 1645 1745 opp. -

1. Parish: Brandon

1. Parish: Brandon Meaning: Broom hill 2. Hundred: Part Forehoe (Norfolk), part Lackford (–1895), Lackford (1895–) Deanery: Fordwich (–1862), Fordwich (Suffolk)(1862–1884), Mildenhall (1884–1962) Union: Thetford RDC/UDC: (W Suffolk) Brandon RD (part)(1894–95), Brandon RD (entirely) (1895–1934), Mildenhall (1935–1974), Forest Heath DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Abolished ecclesiastically to create Brandon Ferry and Wangford 1962 Lackford Petty Sessional Division Thetford County Court District 3. Area: 6,747 acres land, 36 acres water (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Well drained chalk and fine loam over chalk rubble, some deep non-chalk loamy in places. Slight risk water erosion b. Well drained calcareous sandy soils c. Deep well drained sandy soils, in places very acid, risk wind erosion d. Deep permeable sand and peat soils affected by ground water near Little Ouse River 5. Types of farming: 1086 6 acres meadow, 2 fisheries, 2 asses, 11 cattle, 200 sheep, 20 pigs 12th cent. Rabbit warrens 1500–1640 Thirsk: Sheep-corn region, sheep main fertilizing agent, bred for fattening. Barley main cash crop Fen: little or no arable land, commons: hay, grass for animals, peat for fuel 1818 Marshall: Management varies with condition of sandy soils. Rotation usually turnip, barley, clover, wheat or turnips as preparation for corn and grass Fenland: large areas pasture, little ploughed or arable land 1937 Main crops: 2 poultry farmers, 2 dairymen 1969 Trist: Barley and sugar beet are the main crops with some rye grown on poorer lands and a little wheat, herbage seeds and carrots 1 Fenland: Deficiencies in minerals are overcome And these lands are now more suited to arable Farming with wide range of produce grown 6. -

In Memoriam: the Late Earl of Iveagh, K.P. H. T. G

IN MEMORIAM. 365 IN MEMORIAM. THE LATEEARLOF IVEAGH,K.P. On the 7th October, 1927,Lord Iveagh passed to his rest, after a short illness. He had been a member of the SuffolkInstitute of Archxologyfor over twenty years. His generousand wisemunifi- cencein England and Ireland in the cause of education, the better housingof the poor and medicalresearchwill be long remembered. His bequest to the nation ofhis houseat Ken Woodand his magnifi- cent collection of pictures is also well known. His large estate in Suffolk,comprisingthe parishes of Elveden, Eriswell and Icklingham is considereda model one from an agri- cultural and sporting point of view. The hall at Elveden was partly rebuilt and restored by him in the early part of this century, and the celebratedMarbleHall, the details of which weremodelled from examples of ancient Indian art, was completed in 1903. In 1901under the guidance of the Societyfor the Protection of Ancient Buildings,Lord Iveagh re-roofedand restored the church of All Saint's, Icklingham,whichhas many treasures of antiquarian interest. He also restored and re-roofedthe old church of St. Andrew at Elveden and built on a nave, chancel and organ chamber ; using the old church as the South Aisle and a private chapel ; this was consecratedin October, 1906,by'BishopChaseof Ely and dedicated to St. Andrew and St. Patrick ; W. D. Caroe, F.S.A.,F.R.I.A.,was the architect. Later the tall campanilewith peal of ten bells, and the cloisterswere added in memory of Lady Iveagh. The War Memorialto the men of Elveden, Eriswelland Ickling- ham standing at the junction of the three parishes; was erected largely through his generosity; it is a Corinthian column about 120-ft.high on a tall base, surmounted by an urn ; it is visiblefor many miles. -

Situation of Polling Stations West Suffolk

Situation of Polling Stations Blackbourn Electoral division Election date: Thursday 6 May 2021 Hours of Poll: 7am to 10pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Situation of Polling Station Station Ranges of electoral register Number numbers of persons entitled to vote thereat Tithe Barn (Bardwell), Up Street, Bardwell 83 W-BDW-1 to W-BDW-662 Barningham Village Hall, Sandy Lane, Barningham 84 W-BGM-1 to W-BGM-808 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-BHM-1 to W-BHM-471 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-EUS-1 to W-EUS-94 Coney Weston Village Hall, The Street, Coney 86 W-CWE-1 to W-CWE-304 Weston St Peter`s Church (Fakenham Magna), Thetford 87 W-FMA-1 to W-FMA-135 Road, Fakenham Magna, Thetford Hepworth Community Pavilion, Recreation Ground, 88 W-HEP-1 to W-HEP-446 Church Lane Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-HN-VL-1 to W-HN-VL-270 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-SAP-1 to W-SAP-163 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-HOP-1 to W-HOP-500 Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-KNE-1 to W-KNE-19 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXT-1 to W-IXT-53 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXW-1 to W-IXW-1674 Market Weston Village Hall, Church Road, Market 92 W-MWE-1 to W-MWE-207 Weston Stanton Community Village Hall, Old Bury Road, 93 W-STN-1 to W-STN-2228 Stanton Thelnetham Village Hall, School Lane, Thelnetham 94 W-THE-1 to W-THE-224 Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of a Police and Crime Commissioner for Suffolk and where applicable and contested, District Council elections, Parish and Town Council elections and Neighbourhood Planning Referendums. -

TPC Minutes 15 March 2021

TUDDENHAM ST MARY PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting of Tuddenham St Mary Parish Council Held via Zoom, on Monday 15th March 2021 at 7:30pm Councillors present: Cllr. A. Long (AL), Cllr. C. Unwin (CU), Cllr. M. Fitzjohn (MF), Cllr. N. Crockford (NC), Cllr. Amanda Spence (AS) & Cllr. K. Soons (KS) (arr.8:05pm). Present: Clerk – Vicky Bright. Cllr. Brian Harvey – WSC. Rob Gray, (Umbrella). ITEM Public Forum – LGA 1972, Section 100(1): Two members of public were in attendance. 21/03/1 Accepted Apologies for absence – LGA 1972, Section 85(1) and (2): None. Absent: None. 21/03/2 Members Declaration of Interest (for items on the agenda) – LGA 2000 Part III: Cllr. Amanda Spence See Item: 7 (ii) for details. 21/03/3 Update on Councillor Vacancies & Co-Option to fill One Vacancy Cllr. Andrew Long proposed co-opting Amanda Spence onto the Council, this was seconded by Cllr. Nicola Crockford. Resolved 21/03/3.01 The vote was unanimous in favour of co-opting Amanda Spence onto the Council. Cllr. Spence signed her Declaration of Office, this will be duly countersigned by the Clerk upon receipt after the meeting. The Clerk will issue Cllr. Spence with a Register of Interests Form and the Governing documents of the Council after the meeting. 21/03/4 Reports from Outside Bodies: i) SCC – County Councillor – Cllr. Colin Noble gave apologies and the following report was presented. See Appendix 1 ii) WSC – District Councillor – Cllr. Brian Harvey gave the following report to the meeting. See Appendix 2 21/03/5 To Approve the Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on 18th January 2021 Resolved 21/03/4.01 The minutes of the meeting held on 18th January 2021 were adopted as true statements and signed by the Chairman of the meeting (AL). -

Family Services: the Teams and the Education Settings They Support: Academic Year 2020 / 2021

Family Services: The Teams and the Education Settings They Support: Academic Year 2020 / 2021 The SEND Family Services (within SCC Inclusion Service) lead on the support of children, young people and their families so that with the necessary skills, young people progress into adulthood to further achieve their hopes, dreams and ambitions. Fundamental to this is our joint partner commitment to the delivery of services through a key working approach for all. The six locality-based Family Services Teams: • Guide children, young people and their families through their education pathway and/or SEND Journey • Support children and young people who are at risk of exclusion or who have been permanently excluded • Ensure that assessments, including education, health and care needs assessments, provide accurate information and clear advice and are delivered within timescales • Monitor the progress of children and young people with SEND in achieving outcomes to prepare them for adulthood and offer support and guidance at transition points Team members will: • Create trusting relationships with children, young people and families by delivering what they agree to do • Build effective communication and relationships with professionals, practitioners and education settings • Enable the person receiving a service to feel able to discuss any areas of concern / issues and that appropriate action will be taken • Be transparent and honest in the message they are delivering to all, and will give a clear overview of the processes and procedures • Be effective advocates for children, young people and families For young people and families, mainstream schools, local alternative provision and specialist schools, settings and units, your primary contacts will be the Family Services Co-ordinators and Assistant Co-ordinators. -

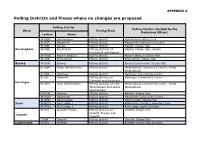

Polling Districts and Places Where No Changes Are Proposed

APPENDIX 2 Polling Districts and Places where no changes are proposed Polling District Polling Station (decided by the Ward Polling Place Returning Officer) Letters Name W-BGM Barningham Polling district Barningham Village Hall W-HEP Hepworth Polling district Hepworth Community Pavilion W-HOP Hopton Polling district Hopton Village Hall Barningham W-KNE Knettishall Polling districts of Hopton Village Hall, Hopton Knettishall and Hopton W-MWE Market Weston Polling district Market Weston Village Hall W-THE Thelnetham Polling district Thelnetham Village Hall Exning W-EXN Exning Polling district Exning Community Church Hall B-GWH Great Whelnetham Polling district Whelnetham Community Centre, Great Whelnetham B-HOR Horringer Polling district Horringer Community Centre B-ICK Ickworth Polling districts of Horringer Community Centre Ickworth and Horringer Horringer B-LWH Little Whelnetham Polling districts of Little Whelnetham Community Centre, Great Whelnetham and Great Whelnetham Whelnetham B-NOW Nowton Polling district Nowton Village Hall W-HAW Hawstead Polling district Hawstead Community Centre W-HER Herringswell Polling district Herringswell Village Hall Iceni W-REL1 Red Lodge 1 Polling district Millennium Centre, Lavender Close W-REL2 Red Lodge 2 Polling district Red Lodge Sports Pavilion W-IXT Ixworth Thorpe Polling districts of Ixworth Village Hall Ixworth Thorpe and Ixworth Ixworth I-IXW Ixworth Polling district Ixworth Village Hall Lakenheath W-ELV Elveden Polling district Elveden Village Hall, Elveden APPENDIX 2 Polling District Polling -

1. Parish: Lakenheath

1. Parish: Lakenheath Meaning: The landing place of Laca’s people or Lacinga’s people at a stream 2. Hundred: Lackford Deanery: Fordwich (–1862), Fordwich (Suffolk) (1862–1884) Mildenhall (1884–) Union: Mildenhall RDC/UDC: Mildenhall RD (–1974), Forest Heath DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Lackford Petty Sessional Division Mildenhall County Court District 3. Area: 11,275 acres, 56 acres water (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Deep well drained sandy soils, some very acid under heath/woodland, risk wind erosion b. Shallow well drained calcareous sand and coarse loam soils over chalk or chalk rubble, some deep sandy soils c. Some deep peat with sand and sometimes gravel 5. Types of farming: 1086 ½ mill, 5 fisheries, 20½ acres meadow, 2 horses at hall, 29 cattle, 162 sheep, 17 pigs, Medieval rabbit warren 1500–1640 Thirsk: Sheep-corn region, sheep main fertilising agent, bred for fattening. Barley main cash crop. Fen: little arable, commons for hay and grass plus peat for fuel 1813 Young 5,000 acres of fen, 2,500 acres of warren, 1,000 acres open field arable, 300 acres common 1818 Marshall: Management varies with condition of sandy soils. Rotation usually turnip, barley, clover, wheat or turnips as preparation for corn and grass. Fenlands: Large areas of pasture with little ploughed or arable land 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley oats, rye. Fruit growers, poultry farmer 1 1969 Trist: Deficiencies in minerals are overcome and these lands are now more suited to arable farming with wide range of produce grown 6. Enclosure: 1820 339 acres enclosed at Undley under Private Acts of Lands 1818 1837 1,067 acres enclosed under Private Acts of Lands 1833 7. -

USAAF AIRFIELDS Guide and Map Introduction

USAAF AIRFIELDS Guide and Map Introduction During the Second World War, the East of England became home to hundreds of US airmen. They began arriving in 1942, with many existing RAF (Royal Air Force) airfields made available to the USAAF (United States Army Air Force). By 1943 there were over 100,000 US airmen based in Britain. The largest concentration was in the East of England, where most of the 8th Air Force and some of the 9th were located on near a hundred bases. The 8th Air Force was the largest air striking force ever committed to battle, with the first units arriving in May 1942. The 9th Air Force was re-formed in England in October 1943 - it was the operator of the most formidable troop-carrying force ever assembled. Their arrival had an immediate impact on the East Anglian scene. This was the 'friendly invasion' - a time of jitterbugging dances and big band sounds, while the British got their first taste of peanut butter, chewing gum and Coke. Famous US bandleader Glenn Miller was based in the Bedford area (Bedfordshire), along with his orchestra during the Second World War. Close associations with residents of the region produced long lasting friendships, sometimes even marriage. At The Eagle pub in Cambridge (Cambridgeshire), and The Swan Hotel at Lavenham (Suffolk), airmen left their signatures on the ceiling/walls. The aircraft of the USAAF were the B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator - used by the Bombardment Groups (BG); and the P-51 Mustang, P-38 Lightning and P-47 Thunderbolt - used by the Fighter Groups (FG). -

Last Train to Barnham! (The Bury and Thetford Railway Company)

Last Train to Barnham! (The Bury and Thetford Railway Company) In my article concerning the historical ‘goings on’ at Barnham Camp in the last issue of the Newsletter, I mentioned the part that was played by the railway in supporting the establishment. This aroused much discussion about the long-defunct rail line so I thought that this could form the basis of another feature - so I started digging! The story that follows is based on research on the Internet, the study of various books and a bit of detective work in looking around the local area. To begin at the beginning…. In the first half of the 18th Century, the main sea-port for Bury St Edmunds trade was Kings Lynn, reached by boat via the River Ouse and Lark Navigations. The building of the Great Eastern Railway, (GER), line between Bury and Ipswich in 1846 would provide an alternative sea-port at reduced costs but would also put the GER in a monopoly position for Bury trade. The years between 1863 and 1866 became the time of ‘Railway Mania’ when every town or village wanted their own railway. Edward and John Greene, brewers in Bury, believed the town needed an alternative outlet to reduce the dependence upon the GER so they applied for, and obtained, an Act of Parliament for the building of a new railway. (As an aside here, and to answer a question that will be on a lot of people’s minds, another Bury brewer, Frederick King, was finding it difficult to compete with Greene so he agreed to an amalgamation in 1877 to form Greene, King and Sons the forerunner of today’s brewery in the town.) So it was that in 1865, Edward Greene and Robert Boby, (Ironmonger and Engineer in the town), set up the Bury and Thetford Railway Company along with two further Directors Peter Huddleston, (Greene’s banking partner), and Hunter Rodwell, (barrister of Ampton Court).