DEREK GREGORY Moving Targets and Violent Geographies FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

Aviation Law and Drones

Aviation Law and Drones The aviation industry is being transformed by the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones – commercially, militarily, scientifically and recreationally. National regulations have generally failed to keep pace with the expansion of the fast-growing drone industry. Aviation Law and Drones: Unmanned Aircraft and the Future of Aviation traces the development of aviation laws and regulations, explains how aviation is regulated at an international and national level, considers the interrelationship between rapidly advancing technology and legislative attempts to keep pace, and reviews existing domestic and international drone laws and issues (including safety, security, privacy and airspace issues). Against this background, the book uniquely proposes a rationale for, and key provisions of, guiding principles for the regulation of drones internationally – provisions of which could also be implemented domestically. Finally, the book examines the changing shape of our increasingly busy skies – technology beyond drones and the regulation of that technology. The world is on the edge of major disruption in aviation – drones are just the beginning. Given the almost universal interest in drones, this book will be of interest to readers worldwide, from the academic sector and beyond. David Hodgkinson is a partner at HodgkinsonJohnston and an associate professor at the University of Western Australia. He is the author of books and numerous journal articles on aviation and climate change, and was Director of Legal at IATA, the organisation of the world’s airlines. Rebecca Johnston is a partner at aviation and aerospace law firm, Hodgkin- sonJohnston, and teaches at the University of Western Australia. She is admitted to practise law in Australia and New York. -

Unmanned: Drone Warfare and Global Security

Unmanned Rogers T02683 00 pre 1 05/03/2014 13:36 Rogers T02683 00 pre 2 05/03/2014 13:36 Unmanned Drone Warfare and Global Security Ann Rogers and John Hill Between the Lines TORONTO Rogers T02683 00 pre 3 05/03/2014 13:36 First published 2014 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 First published in Canada in 2014 by Between the Lines 401 Richmond Street West, Studio 277, Toronto, Ontario M5V 3A8 Canada. 1-800-718-7201 www.btlbooks.com Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Rogers, Ann, 1964-, author Unmanned : drone warfare and global security / Ann Rogers and John Hill. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77113-153-7 (pbk.).—ISBN 978-1-77113-154-4 (epub).— ISBN 978-1-77113-155-1 (pdf) 1. Drone aircraft. 2. Military robots. 3. Security, International. 4. Military weapons (International law). 5. War--Moral and ethical aspects. 6. War and society. I. Hill, John (Journalist), author II. Title. UG1242.D7R65 2014 623.74'69 C2013-907913-0 C2013-907912-2 Copyright © Ann Rogers and John Hill 2014 The right of Ann Rogers and John Hill to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3335 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3334 2 Pluto Press paperback ISBN 978 1 77113 153 7 Between the Lines paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1147 5 Pluto Press PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 77113 155 1 Between the Lines PDF ISBN 978 1 7837 1149 9 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1148 2 epub eBook ISBN 978 1 77113 154 4 Between the Lines epub Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Novel Control Techniques for a Quadrotor Based on the Sliding Mode Controller

University of Cincinnati mechanical and materials engineering Novel control techniques for a quadrotor based on the Sliding Mode Controller A thesis submitted to the Graduate school of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering of the College of Engineering and Applied Science by Madhavan Sudakar M.S. University of Cincinnati Nov 11, 2020 Committee Chair: Manish Kumar, Ph.D. Abstract The thesis focuses on formulating novel mathematical control designs and implementing them on a quadrotor UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle). The novel designs are based on the sliding mode control technique. The conventional sliding mode controller uses information from a sliding surface which comprises of a combination of state errors and a fixed set of stable coefficients. In this thesis, two different sets of objectives are achieved by modifying the conventional architecture. For the first objective, resistance to high external wind disturbance during outdoor quadrotor flight is attempted. This is achieved by incorporating information from not just the sliding surface but also the derivative of the sliding surface into the control input. The second objective involves using a sliding surface whose coefficients are not fixed but variable in nature. It is desired to generate a PD controller that stabilizes the quadrotor dur- ing flight by using this form of sliding surface. To achieve the second objective, two control architectures are presented. In the first, the process of adaptation of the sliding coefficients occurs to reduce the magnitude of state errors to zero. The second algorithm keeps adapting the sliding mode coefficients to the point where they converge at values which form a stable sliding surface. -

The Cultural Impact of Science in the Early Twentieth Century

In the early decades of the twentieth century, engagement with science was commonly used as an emblem of modernity. This phenomenon is now attracting increasing attention in different historical specialties. Being Modern builds on this recent scholarly interest to explore engagement with science across culture from the end of the nineteenth century to approximately 1940. Addressing the breadth of cultural forms in Britain and the western world from the architecture of Le Corbusier to working class British science fiction, Being Modern paints a rich picture. Seventeen distinguished contributors from a range of fields including the cultural study of science and technology, art and architecture, English The Cultural Impact of culture and literature examine the issues involved. The book will be a valuable resource for students, and a spur to scholars to further examination of culture as an Science in the Early interconnected web of which science is a critical part, and to supersede such tired formulations as ‘Science and culture’. Twentieth Century Robert Bud is Research Keeper at the Science Museum in London. His award-winning publications in the history of science include studies of biotechnology and scientific instruments. Frank James and Morag Shiach James and Morag Frank Robert Greenhalgh, Bud, Paul Edited by Paul Greenhalgh is Director of the Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia, Edited by and Professor of Art History there. He has published extensively in the history of art, design, and the decorative arts in the early modern period. Robert Bud Paul Greenhalgh Frank James is Professor of History of Science at the Royal Institution and UCL. -

IMPREGNATED PRESSURE CABLE the ELECTRICIAN June 8, 1945

THE Vol. CXXXIV. No, 3497, Friday, June 8, 1945. Sixpence IMsgitisrsd at th* Q*mra! Past Office Bnsertd as Second Class at the N ea York U.S.A. Post Gjfiee.} W e have designed, manufactured, laid and jointed the World’s first three-core 132,000 volt underground electric cable. Three-core cable provides the most economical and reliable means for the underground transmission of electricity at this voltage. Full particulars in our new PUBLICATION No. 143. 3 - c o r e 1 3 2 k v IMPREGNATED PRESSURE CABLE THE ELECTRICIAN June 8, 1945 at a high standard of quality... The term “ standardisation ” may stand for mere uniformity. At the M.E.M. Factory, however, it means that all production is brought up to a high level of quality, design and finish. The architect who specifies M.E.M. switch and fusegear and the electrician who selects M.E.M. know that a reliable installation is certain and at a reasonable cost. For although M.E.M. gear is good it is not expensive. Good design and modem factory practice have cut out all waste of both materials and man-hours. The M.E.M. Factory is self-contained and self-sufficient. It pro duces good electrical gear from start to finish—good all through. SWITCHCEAR • MOTOR STARTERS FUSEGEAR • ELECTRIC FIRES M .E .M . “ M em roy M Stcitcbifuse. MIDLAND ELECTRIC MANUFACTURING CO. LTD., TYSELEY, BIRMINGHAM, 1' London Showrooms & Stores r 21-22 Rathbone Place, W.l r hlanchester Showrooms & Stores : 48-50 Chapel St.. Salford, 3 June 8, 1945 THE ELECTRICIAN iii Sensitive Instruments are easily damaged by vibration. -

The Evolution of Warfare Volume 97 Number 900 Winter 2015

Volume 97 Number 900 Winter 2015 Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action The evolution of warfare Volume 97 Number 900 Winter 2015 Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action The evolution of warfare CONTENTS The evolution of warfare 959 Editorial: Tactics, techniques, tragedies: A humanitarian perspective on the changing face of war Vincent Bernard, Editor-in-chief 969 Interview with Richard Overy Professor at the University of Exeter A century of warfare 985 Opinion note: How warfare has evolved – ahumanitarianorganization’s perception: The case of the ICRC, 1863-1960 Daniel Palmieri 999 The South African War as humanitarian crisis Elizabeth van Heyningen 1029 The Great War: World war, total war Annette Becker 1047 Will the Trojan War take place? Violations of the rules of war and the Battle of the Dardanelles (1915) Emre Öktem and Alexandre Toumarkine 1065 Out of sight, out of reach: Moral issues in the globalization of the battlefield Eric Germain 1099 The ICRC in the First World War: Unwavering belief in the power of law? Lindsey Cameron 954 Volume 97 Number 900 Winter 2015 Articles published by the Review reflect the views of the author alone and not necessarily those of the ICRC or of the Review. Only texts bearing an ICRC signature may be ascribed to the institution. 1121 “A horrific photo of a drowned Syrian child”: Humanitarian photography and NGO media strategies in historical perspective Davide Rodogno and Heide Fehrenbach 1157 Opinion note: Technological change and the evolution of the law of war Rain Liivoja Challenges in modern -

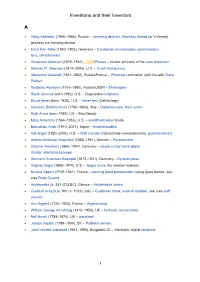

Inventions and Their Inventors A

Inventions and their Inventors A Vitaly Abalakov (1906–1986), Russia – camming devices, Abalakov thread (or V-thread) gearless ice climbing anchor Ernst Karl Abbe (1840–1905), Germany – Condenser (microscope), apochromatic lens, refractometer Hovannes Adamian (1879–1932), USSR/Russia – tricolor principle of the color television Samuel W. Alderson (1914–2005), U.S. – Crash test dummy Alexandre Alexeieff (1901–1982), Russia/France – Pinscreen animation (with his wife Claire Parker) Rostislav Alexeyev (1916–1980), Russia/USSR – Ekranoplan Randi Altschul (born 1960), U.S. – Disposable cellphone Bruce Ames (born 1928), U.S. – Ames test (Cell biology) Giovanni Battista Amici (1786–1863), Italy – Dipleidoscope, Amici prism Ruth Amos (born 1989), UK – StairSteady Mary Anderson (1866–1953), U.S. – windshield wiper blade Momofuku Ando (1910–2007), Japan – Instant noodles Hal Anger (1920–2005), U.S. – Well counter (radioactivity measurements), gamma camera Anders Knutsson Ångström (1888–1981), Sweden – Pyranometer Ottomar Anschütz (1846–1907), Germany – single-curtain focal-plane shutter, electrotachyscope Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe (1872–1931), Germany – Gyrocompass Virginia Apgar (1909–1974), U.S. – Apgar score (for newborn babies) Nicolas Appert (1749–1841), France – canning (food preservation) using glass bottles, see also Peter Durand Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC), Greece – Archimedes' screw Guido of Arezzo (c. 991–c. 1033), Italy – Guidonian hand, musical notation, see also staff (music) Ami Argand (1750–1803), France – Argand lamp William George Armstrong (1810–1900), UK – hydraulic accumulator Neil Arnott (1788–1874), UK – waterbed Joseph Aspdin (1788–1855), UK – Portland cement John Vincent Atanasoff (1903–1995), Bulgaria/U.S. – electronic digital computer 1 Inventions and their Inventors B Charles Babbage (1791–1871), UK – Analytical engine (semi-automatic) Tabitha Babbit (1779–1853), U.S. -

Download PDF Of

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (900), 1065–1097. The evolution of warfare doi:10.1017/S1816383116000461 Out of sight, out of reach: Moral issues in the globalization of the battlefield E´ric Germain* E´ric Germain is a historian and specialist in the anthropology of religion. Since 2009 he has been reflecting on the ethics of newly emerging weapons technology. Abstract The Great War ushered in a new era of long-distance combat. For the first time, weapons with a very long range were massively deployed, in previously unheard-of places: under the sea and in the air. Stealth fighting also included espionage and propaganda, now orchestrated on a global scale. In reaction to the carnage in the trenches, a degree of moral rehabilitation came to be conferred on the weapons initially associated with a “cowards’ war”. This in turn encouraged experimentation with the new, unmanned technology that would lead to the first prototypes of guided munitions and drones. Keywords: Great War, First World War, Second World War, weapons technology, strategic bombing, U-boat, Zeppelin, drone, robot, cyber, guided munition, espionage, propaganda, censorship, jihad, special forces, post-traumatic stress disorder, international humanitarian law, ethics, stealth, disengaged combat, lethal autonomous weapons systems. * The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author, writing in his private capacity. He wishes to dedicate his article to his great grandfather, Louis Gousseau, who served as a Major in the infantry during the First World War, and to his great grand-mother Laure and her sisters, Acélie and Louise, who served as volunteer nurses in a military hospital under the banner of the Red Cross. -

An Application of Aerial Drones in Zoning and Urban Land Use Planning in Canada

AN APPLICATION OF AERIAL DRONES IN ZONING AND URBAN LAND USE PLANNING IN CANADA A Preliminary Review of Current Policies, Restrictions and Planning Direction for Aerial Drones in Canadian Cities By Nathan Alexander Lindo Jenkins B.Sc.(Env.), University of Guelph, 2013 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Planning In Urban Development Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Nathan Jenkins 2015 Author’s Declaration for Electronic Submission of a MRP I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. ii AN APPLICATION OF AERIAL DRONES IN ZONING AND URBAN LAND USE PLANNING IN CANADA A Preliminary Review of Current Policies, Restrictions and Planning Direction for Aerial Drones in Canadian Cities © Nathan Jenkins, 2015 Master of Planning In Urban Development Ryerson University ABSTRACT The rapidly changing technology of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), or drones, has potential uses in many aspects of urban life, including in the planning profession. Compared with current alternatives, UAVs could potentially provide a superior low cost, adaptable and accurate data gathering tool for planners.