No Evidence for the 'Rate-Of-Living' Theory Across the Tetrapod Tree of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herpetofaunal Diversity of Çanakkale Southwest Coastal Zones

Turkish Journal of Bioscience and Collections Volume 4, Number 2, 2020 E-ISSN: 2601-4292 RESEARCH ARTICLE Herpetofaunal Diversity of Çanakkale Southwest Coastal Zones Begüm Boran1 , İbrahim Uysal1 , Murat Tosunoğlu1 Abstract Along with the literature information obtained from previous studies, the determination of species in herpetofauna studies gives information about the herpetofauna of the research 1Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Science and Art, Department of Biology, area. Researching the herpetofauna of regions is very important in terms of conservation of Çanakkale, Turkey species, revealing biodiversity, identifying possible threats, and determining the preventitive measures to be taken against these threats. ORCID: B.B. 0000-0002-3069-7780; The study area is the southwestern coastal regions of Çanakkale, which is also the İ.U. 0000-0001-7180-5488; M.T. 0000-0002-9764-2477 westernmost coast of Anatolia. This area consists of the localities of Ahmetçe, Sazlı, Kozlu, Behram, Bektaş, Koyunevi, Babakale, Gülpınar, Tuzla, Kösedere, and Tavaklı. Received: 11.06.2020 Because it has the potential to be a coastline separated by the end of the Kaz Mountains, Revision Requested: 18.06.2020 Last Revision Received: 21.07.2020 this study area has different habitats and has the potential to host species that exceed Accepted: 17.08.2020 isolation of the Kaz Mountains. In this study, the amphibian and reptile diversity of terrestrial and aquatic areas along the Correspondence: Begüm Boran [email protected] coast of Southwest Anatolia starting from the end of the Kaz Mountains, which is the habitat preferences of the species, and the effects of environmental and anthropogenic Citation: Boran, B., Uysal, I., & Tosunoglu, factors on the herpetofauna of the region were investigated. -

The First Miocene Fossils of Lacerta Cf. Trilineata (Squamata, Lacertidae) with A

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/612572; this version posted April 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. The first Miocene fossils of Lacerta cf. trilineata (Squamata, Lacertidae) with a comparative study of the main cranial osteological differences in green lizards and their relatives Andrej Čerňanský1,* and Elena V. Syromyatnikova2, 3 1Department of Ecology, Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynská dolina, 84215, Bratislava, Slovakia 2Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya 123, 117997 Moscow, Russia 3Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab., 1, St. Petersburg, 199034 Russia * Email: [email protected] Running Head: Green lizard from the Miocene of Russia Abstract We here describe the first fossil remains of a green lizardof the Lacerta group from the late Miocene (MN 13) of the Solnechnodolsk locality in southern European Russia. This region of Europe is crucial for our understanding of the paleobiogeography and evolution of these middle-sized lizards. Although this clade has a broad geographical distribution across the continent today, its presence in the fossil record has only rarely been reported. In contrast to that, the material described here is abundant, consists of a premaxilla, maxillae, frontals, bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/612572; this version posted April 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

For Review Only

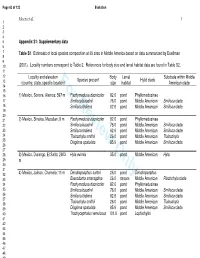

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Herpetological Review

Herpetological Review Volume 41, Number 2 — June 2010 SSAR Offi cers (2010) HERPETOLOGICAL REVIEW President The Quarterly News-Journal of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles BRIAN CROTHER Department of Biological Sciences Editor Southeastern Louisiana University ROBERT W. HANSEN Hammond, Louisiana 70402, USA 16333 Deer Path Lane e-mail: [email protected] Clovis, California 93619-9735, USA [email protected] President-elect JOSEPH MENDLELSON, III Zoo Atlanta, 800 Cherokee Avenue, SE Associate Editors Atlanta, Georgia 30315, USA e-mail: [email protected] ROBERT E. ESPINOZA KERRY GRIFFIS-KYLE DEANNA H. OLSON California State University, Northridge Texas Tech University USDA Forestry Science Lab Secretary MARION R. PREEST ROBERT N. REED MICHAEL S. GRACE PETER V. LINDEMAN USGS Fort Collins Science Center Florida Institute of Technology Edinboro University Joint Science Department The Claremont Colleges EMILY N. TAYLOR GUNTHER KÖHLER JESSE L. BRUNNER Claremont, California 91711, USA California Polytechnic State University Forschungsinstitut und State University of New York at e-mail: [email protected] Naturmuseum Senckenberg Syracuse MICHAEL F. BENARD Treasurer Case Western Reserve University KIRSTEN E. NICHOLSON Department of Biology, Brooks 217 Section Editors Central Michigan University Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA Book Reviews Current Research Current Research e-mail: [email protected] AARON M. BAUER JOSHUA M. HALE BEN LOWE Department of Biology Department of Sciences Department of EEB Publications Secretary Villanova University MuseumVictoria, GPO Box 666 University of Minnesota BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia St Paul, Minnesota 55108, USA P.O. Box 58517 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Salt Lake City, Utah 84158, USA e-mail: [email protected] Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Immediate Past President ALAN M. -

Molekularno-Filogenetičke I Morfološke Značajke Zelenih Žaba (Rod Pelophylax) U Hrvatskoj

Molekularno-filogenetičke i morfološke značajke zelenih žaba (rod Pelophylax) u Hrvatskoj Schmidt, Bruno Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:811997 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-04 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb Sveučilište u Zagrebu Prirodoslovno – matematički fakultet Biološki odsjek Bruno Schmidt Molekularno–filogenetičke i morfološke značajke zelenih žaba (rod Pelophylax) u Hrvatskoj Diplomski rad Zagreb, 2018. Ovaj rad izrađen je na Zoologijskom zavodu Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, pod vodstvom prof. dr. sc. Görana Klobučara i pomoćnim voditeljstvom dr. sc. Mišela Jelića. Rad je predan na ocjenu Biološkom odsjeku Prirodoslovnog-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu radi stjecanja zvanja magistra znanosti o okolišu. 2 Najljepše zahvaljujem mentoru dr. sc. Göranu Klobučaru na ukazanom povjerenju, stručnom vodstvu te vremenu i trudu kojeg je uložio. Najveća hvala dr. sc. Mišelu Jeliću koji me vodio kroz ovo istraživanje, rješavao sve probleme i prepreke, značajno unaprijedio moje znanje i pokazao mi kako se pravilno izvodi znanstveno istraživanje. Velika hvala svim starim i novim prijateljima koje stekao tijekom svog akademskog obrazovanja, koji su mi pružili potporu -

Morphological Alterations in the External Gills of Some Tadpoles in Response to Ph

THIEME 142 Original Article Morphological Alterations in the External Gills of Some Tadpoles in Response to pH CaressaMaebhaThabah1 Longjam Merinda Devi1 Rupa Nylla Kynta Hooroo1 Sudip Dey2 1 Developmental Biology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, North- Address for correspondence Caressa Maebha Thabah, PhD in Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Zoology, Developmental Biology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, 2 Electron Microscope Laboratory, Sophisticated Analytical Instrument North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong 793022, Meghalaya, India Facility, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India (e-mail: [email protected]). J Morphol Sci 2018;35:142–152. Abstract Introduction Water pH affects the breeding, hatching, development, locomotion, mortality and habitat distributions of species in nature. The external gills of anuran tadpoles were studied by several authors in relation to abiotic factors. Exposure to low and high pH has been found to adversely affect the different tissues of various organisms. On that consideration, the present investigation was performed with tadpoles of the species Hyla annectans and Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis. Material and Methods The maximum and the minimum pH thresholds were determined prior to the detailed experiments on the effects of pH. The pH that demonstrated 50% mortality was taken as the minimum and maximum pH thresholds. The hatchlings of both the species were then subjected to different pH (based on the minimum and maximum pH thresholds). After 48 hours of exposure, the external gills of the hatchlings were anesthetized and observed under a scanning electron microscope. Keywords Results After 48 hours, clumping, overlapping and curling of the secondary filaments ► Hyla annectans of the external gills and epithelial lesions in response to both acidic and alkaline pH ► Euphlyctis were observed. -

A Description of a New Subspecies of Rock Lizard Darevskia Brauneri Myusserica Ssp

Труды Зоологического института РАН Том 315, № 3, 2011, c. 242–262 УДК 598.113.6 ОПИСАНИЕ НОВОГО ПОДВИДА СКАЛЬНОЙ ЯЩЕРИЦЫ DAREVSKIA BRAUNERI MYUSSERICA SSP. NOV. ИЗ ЗАПАДНОГО ЗАКАВКАЗЬЯ (АБХАЗИЯ) C КОММЕНТАРИЯМИ ПО СИСТЕ МАТИКЕ КОМПЛЕКСА DAREVSKIA SAXICOLA И.В. Доронин Зоологический институт Российской академии наук, Университетская наб. 1, 199034 Санкт-Петербург, Россия; e-mail: [email protected] РЕЗЮМЕ В статье приводится описание нового подвида скальной ящерицы комплекса Darevskia saxicola, обитающего на территории Пицундо-Мюссерского заповедника и в районе г. Гагра Республики Абхазия. Мюссерская ящерица, Darevskia brauneri myusserica ssp. nov., отличается от других таксонов комплекса следующей ком- бинацией морфологических признаков: (1) крупный или очень крупный центральновисочный щиток; (2) прерывистый ряд ресничных зернышек между верхнересничными и надглазничными щитками; (3) наличие дополнительных щитков, лежащих по обе стороны от затылочного и межтеменного щитков, либо дробление последнего; (4) сетчатый рисунок на спине (у самок нечеткий); (5) доминирование у самок серого и светло- серого цвета в окраске дорсальной поверхности тела; (6) белое горло и брюхо. Кроме того, новый подвид отличается некоторыми особенностями биологии: биотопической приуроченностью к прибрежным выходам конгломерата и относительно низкой численностью популяции. Предположительно, формирование таксона протекало в плейстоцене. Образование приморской равнины полуострова Пицунда за счет аллювиальной и морской аккумуляции в позднем неоплейстоцене – голоцене разделило ареал мюссерской ящерицы на гагр- ский и мюссерский участки. Эта территория расположена в пределах Черноморского рефугиума восточно- средиземноморских видов герпетофауны. Ключевые слова: Абхазия, комплекс Darevskia saxicola, скальные ящерицы, Darevskia brauneri myusserica ssp. nov. A DESCRIPTION OF A NEW SUBSPECIES OF ROCK LIZARD DAREVSKIA BRAUNERI MYUSSERICA SSP. NOV. FROM THE WESTERN TRANSCAUCASIA (ABKHAZIA), WITH COMMENTS ON SYSTEMATICS OF DAREVSKIA SAXICOLA COMPLEX I.V. -

An Overview and Checklist of the Native and Alien Herpetofauna of the United Arab Emirates

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 5(3):529–536. Herpetological Conservation and Biology Symposium at the 6th World Congress of Herpetology. AN OVERVIEW AND CHECKLIST OF THE NATIVE AND ALIEN HERPETOFAUNA OF THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 1 1 2 PRITPAL S. SOORAE , MYYAS AL QUARQAZ , AND ANDREW S. GARDNER 1Environment Agency-ABU DHABI, P.O. Box 45553, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, e-mail: [email protected] 2Natural Science and Public Health, College of Arts and Sciences, Zayed University, P.O. Box 4783, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Abstract.—This paper provides an updated checklist of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) native and alien herpetofauna. The UAE, while largely a desert country with a hyper-arid climate, also has a range of more mesic habitats such as islands, mountains, and wadis. As such it has a diverse native herpetofauna of at least 72 species as follows: two amphibian species (Bufonidae), five marine turtle species (Cheloniidae [four] and Dermochelyidae [one]), 42 lizard species (Agamidae [six], Gekkonidae [19], Lacertidae [10], Scincidae [six], and Varanidae [one]), a single amphisbaenian, and 22 snake species (Leptotyphlopidae [one], Boidae [one], Colubridae [seven], Hydrophiidae [nine], and Viperidae [four]). Additionally, we recorded at least eight alien species, although only the Brahminy Blind Snake (Ramphotyplops braminus) appears to have become naturalized. We also list legislation and international conventions pertinent to the herpetofauna. Key Words.— amphibians; checklist; invasive; reptiles; United Arab Emirates INTRODUCTION (Arnold 1984, 1986; Balletto et al. 1985; Gasperetti 1988; Leviton et al. 1992; Gasperetti et al. 1993; Egan The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of 2007). -

Thermal Adaptation of Amphibians in Tropical Mountains

Thermal adaptation of amphibians in tropical mountains. Consequences of global warming Adaptaciones térmicas de anfibios en montañas tropicales: consecuencias del calentamiento global Adaptacions tèrmiques d'amfibis en muntanyes tropicals: conseqüències de l'escalfament global Pol Pintanel Costa ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Hylidae, Anura) and Description of Ocellated Treefrog Itapotihyla Langsdorffii Vocalizations

Current knowledge on bioacoustics of the subfamily Lophyohylinae (Hylidae, Anura) and description of Ocellated treefrog Itapotihyla langsdorffii vocalizations Lucas Rodriguez Forti1, Roseli Maria Foratto1, Rafael Márquez2, Vânia Rosa Pereira3 and Luís Felipe Toledo1 1 Laboratório Multiusuário de Bioacústica (LMBio) e Laboratório de História Natural de Anfíbios Brasileiros (LaHNAB), Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 2 Fonoteca Zoológica, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Madrid, Spain 3 Centro de Pesquisas Meteorológicas e Climáticas Aplicadas à Agricultura (CEPAGRI), Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil ABSTRACT Background. Anuran vocalizations, such as advertisement and release calls, are informative for taxonomy because species recognition can be based on those signals. Thus, a proper acoustic description of the calls may support taxonomic decisions and may contribute to knowledge about amphibian phylogeny. Methods. Here we present a perspective on advertisement call descriptions of the frog subfamily Lophyohylinae, through a literature review and a spatial analysis presenting bioacoustic coldspots (sites with high diversity of species lacking advertisement call descriptions) for this taxonomic group. Additionally, we describe the advertisement and release calls of the still poorly known treefrog, Itapotihyla langsdorffii. We analyzed recordings of six males using the software Raven Pro 1.4 and calculated the coefficient Submitted 24 February 2018 of variation for classifying static and dynamic acoustic properties. Accepted 30 April 2018 Results and Discussion. We found that more than half of the species within the Published 31 May 2018 subfamily do not have their vocalizations described yet. Most of these species are Corresponding author distributed in the western and northern Amazon, where recording sampling effort Lucas Rodriguez Forti, should be strengthened in order to fill these gaps.