The Nerve to Break Taboos Prins, Baukje

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Het Redactiestatuut Van Landelijke, Regionale En Lokale Nederlandse Kranten

Het redactiestatuut van landelijke, regionale en lokale Nederlandse kranten Een gedateerd document of een waardevolle toevoeging voor de onafhankelijkheid van de journalistiek? Masterthesis Naam: Anne Wielenga Studentnummer: s1151142 Media studies: Journalism & New Media Begeleider: prof. dr. J.C. de Jong Tweede lezer: dr. J.P. Burger 31-03-2017 ii Voorwoord Voor u ligt mijn masterscriptie ‘Het redactiestatuut van landelijke, regionale en lokale Nederlandse kranten. Een gedateerd document of een waardevolle toevoeging voor de onafhankelijkheid van de journalistiek?’, die geschreven is in het kader van mijn afstuderen voor de master Journalistiek en Nieuwe Media aan Universiteit Leiden. In de periode van november 2016 tot en met maart 2017 ben ik bezig geweest met het uitvoeren van het onderzoek en het schrijven van deze scriptie. Aanvankelijk stond ik wat sceptisch tegenover het onderwerp ‘redactiestatuten’, maar het heeft uiteindelijk mijn enthousiasme gewekt. Wat aanvankelijk de opzet voor een onderzoek van het Commissariaat voor de Media had moeten worden, is omgebogen naar een eigen onderzoek waarbij ik aspecten die ik belangrijk vond, heb uitgediept en uitgewerkt. De resultaten van dit onderzoek zijn interessant voor instanties die geïnteresseerd zijn in de bescherming van de onafhankelijkheid van nieuwsmedia, zoals het Commissariaat voor de Media en de Nederlandse Vereniging van Journalisten, maar ook voor media die willen weten hoe ze deze onafhankelijkheid kunnen waarborgen in hun redactiestatuut. Ik wil in het bijzonder mijn begeleider, prof. dr. Jaap de Jong, bedanken voor zijn tijd, wijze woorden en kritische vragen die mijn scriptie vorm en inhoud hebben gegeven. Hier hebben mijn groepsgenoten Jeroen Jonkers en Stef Arends ook zeker aan bijgedragen. -

Beyond Pluralism?

RESEARCH MASTER POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, LEIDEN UNIVERSITY Religious Pluralism A study on the declining protection of religion in the Netherlands Marthe A. Harkema S1153560 Leiden, 15 August, 2013 Master thesis Department of Political Science Leiden University Supervisor: Dr. F. de Zwart Second reader: Dr. F. Ragazzi Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Research topic ................................................................................................................................. 3 Research Approach .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Religious pluralism in the Netherlands ............................................................................................. 10 The historical and institutional background of religious pluralism ............................................... 10 Principled pluralism ....................................................................................................................... 12 The protection of religion by the court and in parliament ........................................................... 15 The court’s protection of religion .................................................................................................. 16 Parliament’s protection of religion .............................................................................................. -

Gezien, Gehoord, Gelezen

Gezien, gehoord, gelezen Peter Bak Een 'meneer'van een krant. Trouw en Bruins Slot 1943-1968 Kampen (Kok), 1999, 440 p., geïll., ƒ75, ISBN 90-435-01-52-2 Jan-Jaap van den Berg Deining. Koers en karakter van de ARP ter discussie, 1956-1970 Kampen (Kok), 1999, 492 p., geïll., ƒ75, ISBN 90-435-01-51-4 In de geschiedenis van de Nederlandse jour Kwartet-b\aden is de spreekwoordelijke uitzon nalistiek zijn twee soorten hoofdredacteuren dering - geleid door hoofdartikelschrijvers. In te vinden: Enerzijds was er de journalistieke Friesland zetelde Hendrik Algra die thuis zijn hoofdredacteur die 'de krant in de palm van geselende commentaren schreef; op de redac zijn hand had'. Joop Lücker van de Volkskrant, tie van zijn Friesch Dagblad liet hij zich zelden gepokt en gemazeld in de Angelsaksische tra zien. De dagelijkse leiding was in handen van ditie, was daarvan de belangrijkste exponent. een redactiechef. Anderzijds was er de politieke hoofdredacteur- Het ARP-kamerlid j.A.H.j.S. Bruins Slot een functie die vaak werd bekleed door een werd in 1945 hoofdredacteur van het voor politicus. Hij belichaamde de band tussen malige verzetsblad Trouw. Peter Bak wilde een krant en partij. In de theorievorming over ver geschiedenis van deze krant schrijven, maar zuiling is, met name door A. Lijphart, veel be stuitte daarbij op problemen. Een redactie lang gehecht aan deze interlocking directorates. archief van Trouw is er niet en Bruins Slot liet Zij waren de ultieme uitdrukking van de sym bijna niets na met betrekking tot de krant. De biotische relatie tussen pers en politiek in het leggers waren daarom Baks belangrijkste bron. -

Rate Card 2021 Mediahuis Print - V1 - 01-02-2021 Print De Telegraaf Rate Card 2021 De Telegraaf

Mediahuis Connect Mediahuis Connect Mediahuis Connect De Telegraaf Regional Total Nationwide + Regional Connect Regional CPM CPM CPM CPM CPM €26,50 €26,50 €33,50 €27,50 €38,50 De Telegraaf De Telegraaf *Regional North De Telegraaf 1 regional title en/of *Regional North *Regional North *Regional South en/of 1.466.300 382.200 Number of contacts Number of contacts *Regional South *Regional South *Regional West depending on deployment depending on deployment *Regional West *Regional West 1.512.900 Number of contacts depending on deployment 44 local news magazines and door-to-door newspapers 2.979.200 Number of contacts depending on deployment 3.970.600 Number of contacts Connect Total *Regional North (NDC Mediagroep): Dagblad van het Noorden, Leeuwarder Courant, Friesch dagblad *Regional South (Mediahuis Limburg): De Limburger *Regional West (Mediahuis Nederland): Noordhollands Dagblad, Haarlems dagblad, IJmuider Courant, Leidsch dagblad, De Gooi- en Eemlander Tarieven Mediahuis Connect Mediahuis Connect CPM X Reach x 1,000 contacts X Size factor X Position factor = Gross page price (1/1) Newspapers, door-to-door newspapers Gross Mon thru Fri Sa Share Factor Guaranteed positions Factor Mon thru Fri Sa and local news magazines Mediahuis Connect € 26.50 3,970.6 1 1.0000 Back page 1.5 € 105,221 1/2 0.6800 Newspapers Mon thru Fri Sa 1/4 0.3000 Mon thru Fri Sa Mediahuis Connect Nationwide and Regional € 26.50 2,374.0 2,979.2 € 62,911 € 78,949 Mediahuis Connect Regional € 33.50 1,306.1 1,512.9 € 43,754 € 50,682 Mediahuis Connect Regional North -

Press Release

Neil Fortune: Colorful Ribs and Guts of Adam Main Gallery Aimée Terburg: Tending Shapes - Bending Colors Second Gallery Exhibitions Reception: Saturday, October 19, 6:00 - 08:00 PM Neil Fortune and Aimée Terburg will be present during exhibition opening. On View Through: November 30, 2019 Gray Contemporary | 3508 Lake Street, Houston, Texas 77098 Neil Fortune, A WORLD AWAY, State of limbo, textile, polyester and paint, size variable, 2017 Page !1 of !12 Neil Fortune: Colorful ribs and guts of Adam Main Gallery Fortune creates works with a strong interest in the social dimension of art objects. Touching upon different media and artist positions, from sculpture to architecture, paintings to performance, having as a common thread a strong engagement with social dilemmas he crosses boundaries between disciplines. His research is mainly developed in the studio, a preferred locus in which his practice unfolds for the public space. At Gray Contemporary Fortune exhibits a series of sculptures suspended in a liminal space between painting and sculpture. Fortune presents a compelling series of works that he describes as hybrid sculpture. The works are sewn on a machine, made of textile, polyester-fiber, isolation foam and a variable mixture of paints, varnish, wood-glue, many of the material he would use to construct paintings and sculpture. He dips the textile into liquid paint. This procedure is repeated until the paint dries. These works first emerged as experiment at a time Fortune was simultaneously working on two projects: a series of his Social Sculpture (that is made of white textile sewn on a machine to be arranged on the gallery floor, setup to invite visitors to engage in a physical dialog with the sculpture), and his architectural painting done on canvas (depicting large and empty spaces mainly behind the scene of a situation, such as exhibition openings or theater stages). -

Leeuwarden-Ljouwert's Application for European Capital of Culture 2018

Leeuwarden-Ljouwert’s application for European Capital of Culture 2018 leeuwarden-ljouwert iepen mienskip REFERENCE GUIDE Afsluitdijk 32km man-made enclosure dam Natuurmuseum Fryslân Frisian Nature Afûk Organisation to promote Frisian Museum Symbols for art forms & disciplines Language and Culture Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid ARK Fryslân Floating architectural centre Netherlands Institute for Sound and Blokhuispoort Former prison built around Vision 1500, now a cultural beehive Nederlandse Museum Vereniging BUOG Inventors and executers of Association of Dutch Museums extraordinary events NOM Development Agency Northern Dairy Campus A base in Leeuwarden from Netherlands agricultural university of Wageningen Noordelijke Hogeschool Leeuwarden (NHL) with a focus on innovation University of Applied Sciences De Kruidhof Botanic garden in Fryslân Noordelijk Film Festival Film festival taking architecture/design performing arts/theatre D’Drive Friesland College Art division of place in Leeuwarden-Ljouwert and on a the Friesland College number of Wadden islands Doarpswurk Organisation that stimulates Noorderslag ETEP European Talent the social cohesion and sustainability of Exchange Programme the Frisian Countryside OECD Organisation for Economic Co- Elfstedentocht Skating tour on natural operation and Development ice that covers all 11 cities in Fryslân, Oerol Annual international theatre festival attracting over 1.5 million visitors on the island of Terschelling cultural heritage/history photography EUNIC European Union National -

2 March 2005 COURT of the HA

IN THE NAME OF THE QUEEN rvp\I + II Case number: 192880 Cause list number: 03-57 Date of judgement: 2 March 2005 COURT OF THE HAGUE Civil Law Sector & Full Court Judgement in the case under the case number and cause list number mentioned above of: 1. the foundation De Nederlandse Dagbladpers, domiciled in Amsterdam, 2. the private company with limited liability Koninklijke BDU Uitgeverij B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 3. the private company with limited liability Het Financieele Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 4. the private company with limited liability Friesch Dagblad Holding B.V., domiciled in Leeuwarden, 5. the private company with limited liability Nedag Beheer B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 6. the private company with limited liability Nederlandse Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Barneveld, 7. the private company with limited liability NCD Holding B.V., domiciled in Groningen, 8. the private company with limited liability Friese Pers B.V., domiciled in Leeuwarden, 9. the private company with limited liability Hazewinkel Pers B.V., domiciled in Groningen, 10. the limited liability company PCM Uitgevers N.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 11. the private company with limited liability PCM Landelijke Dagbladen B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 12. the private company with limited liability Algemeen Dagblad B.V., domiciled in Rotterdam, 13. the private company with limited liability NRC Handelsblad B.V., domiciled in Rotterdam, 14. the private company with limited liability Trouw B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 15. the private company with limited liability De Volkskrant B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 16. the private company with limited liability Het Parool B.V., domiciled in Amsterdam, 17. -

Bronnenlijst Artikelpro ID Uitgever Publicatie Type Publicatie URL

Bronnenlijst ArtikelPro ID uitgever Publicatie Type Publicatie URL 1 DPG Media Algemeen Dagblad AD Landelijke Dagbladen 2 DPG Media Volkskrant Landelijke Dagbladen 3 DPG Media Trouw Landelijke Dagbladen 4 DPG Media Trouw Letter & Geest Landelijke Dagbladen 5 DPG Media Trouw Tijd Landelijke Dagbladen 6 Mediahuis De Telegraaf Landelijke Dagbladen 7 Mediahuis NRC Handelsblad Landelijke Dagbladen 8 Mediahuis NRC Next Landelijke Dagbladen 10Nederlands Dagblad B.V. Nederlands Dagblad Landelijke Dagbladen 11 Reformatorisch Dagblad B.V. Reformatorisch Dagblad Landelijke Dagbladen 12 Reformatorisch Dagblad B.V. Reformatorisch Dagblad Tabloid incidenteel Landelijke Dagbladen 13 Reformatorisch Dagblad B.V. Reformatorisch Dagblad tijdschrift incidenteel Landelijke Dagbladen 14 DPG Media Brabants Dagblad BD Regionale Dagbladen 15 DPG Media BN Den Stem Regionale Dagbladen 16 DPG Media De Stentor Regionale Dagbladen 17 DPG Media Eindhovens Dagblad Regionale Dagbladen 18 DPG Media De Gelderlander Regionale Dagbladen 19 DPG Media Parool Regionale Dagbladen 20 DPG Media PZC Provinciaals Zeeuwse Courant Regionale Dagbladen 21 DPG Media Tubantia Twentsche Courant Regionale Dagbladen 22 DPG Media AD Midden Nederland Regionale Dagbladen 23 DPG Media AD Zuid-Holland Regionale Dagbladen 24 Mediahuis De Gooi en Eemlander Regionale Dagbladen 25 Mediahuis Haarlems Dagblad Regionale Dagbladen 26 Mediahuis Ijmuider Courant Regionale Dagbladen 27 Mediahuis Leidsch Dagblad Regionale Dagbladen 28 Mediahuis Noord Hollands Dagblad Regionale Dagbladen 29Friesch Dagblad -

A Case Study of Value-Conflicts on Dutch Rural Land Use

Polder Limits A Case Study of Value-Conflicts on Dutch Rural Land Use Wiebren Johannes Boonstra Promotoren: Prof.dr.ir. J.D. van der Ploeg, hoogleraar transitieprocessen in Europa Prof.dr.ir. A. van den Brink, hoogleraar bestuurlijke en beleidsmatige aspecten van de landinrichting Copromotor: Dr.ir. B.B. Bock, universitair docent leerstoelgroep rurale sociologie Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof.dr.ir. C. Leeuwis, Wageningen Universiteit Prof.dr. H.J.M. Goverde, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen en Wageningen Universiteit Dr. S. Shortall, Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland Dr. C. Waldenström, Swedish Agricultural University, Uppsala, Sweden Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoekschool Mansholt Graduate School Polder Limits A Case Study of Value-Conflicts on Dutch Rural Land Use Wiebren Johannes Boonstra Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, prof.dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 30 oktober 2006 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula ISBN nr 90 8504 505 3 Table of Contents page Preface VII Voorwoord IX Part 1 Value-conflicts in theory 1 Value-conflicts on rural land use 1 2 Value incommensurability and power: A confrontation between 13 Habermas and Foucault Part 2 Value-conflicts in practice 21 3 Conflicts about water: A case study of contest and power in Dutch rural 23 policy 4 How to account for stakeholders’ perceptions in Dutch rural policy 47 5 Koningsdiep: About Dutch rural policy, power and an environmental 59 -

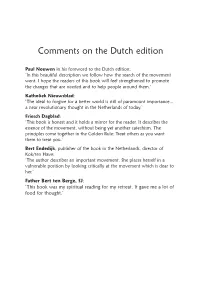

Comments on the Dutch Edition

Comments on the Dutch edition Paul Nouwen in his foreword to the Dutch edition: ‘In this beautiful description we follow how the search of the movement went. I hope the readers of this book will feel strengthened to promote the changes that are needed and to help people around them.’ Katholiek Nieuwsblad: ‘The ideal to forgive for a better world is still of paramount importance... a near revolutionary thought in the Netherlands of today.’ Friesch Dagblad: ‘This book is honest and it holds a mirror for the reader. It describes the essence of the movement, without being yet another catechism. The principles come together in the Golden Rule: Treat others as you want them to treat you.’ Bert Endedijk, publisher of the book in the Netherlands, director of Kok/ten Have: ‘The author describes an important movement. She places herself in a vulnerable position by looking critically at the movement which is dear to her.’ Father Bert ten Berge, SJ: ‘This book was my spiritual reading for my retreat. It gave me a lot of food for thought.’ Reaching for a new world Initiatives of Change seen through a Dutch window Hennie de Pous-de Jonge CAUX BOOKS First published in 2005 as Reiken naar een nieuwe wereld by Uitgeverij Kok – Kampen The Netherlands This English edition published 2009 by Caux Books Caux Books Rue de Panorama 1824 Caux Switzerland © Hennie de Pous-de Jonge 2009 ISBN 978-2-88037-520-1 Designed and typeset in 10.75pt Sabon by Blair Cummock Printed by Imprimerie Pot, 78 Av. des Communes-Réunies, 1212 Grand-Lancy, Switzerland Contents Preface -

Mediamonitor – Mediabedrijven En Mediamarkten 2009

commissariaat voor de media Hoge Naarderweg 78 lllll 1217 AH Hilversum lllll Postbus 1426 lllll 1200 BK Hilversum lllll T 035 773 77 00 lllll F 035 773 77 99 lllll [email protected] lllll www.cvdm.nl lllll mediamonitor mediabedrijven en mediamarkten 2009 © juni 2010 Commissariaat voor de Media Colofon De Mediamonitor is een uitgave van het Commissariaat voor de Media Redactie Marcel Betzel Edmund Lauf Rini Negenborn Jan Vosselman Bosch Vormgeving Studio FC Klap Druk Roto Smeets GrafiServices Commissariaat voor de Media Hoge Naarderweg 78 lllll 1217 AH Hilversum Postbus 1426 lllll 1200 BK Hilversum T 035 773 77 00 lllll F 035 773 77 99 lllll [email protected] lllll www.cvdm.nl lllll www.mediamonitor.nl ISSN 1874-0111 inhoud Voorwoord 5 Samenvatting 7 1. Trends en ontwikkelingen 11 2. Mediabedrijven 19 3. Mediamarkten 39 3.1 Dagbladen 40 3.2 Opiniebladen 48 3.3 Televisie 49 3.4 Radio 57 3.5 Internet 66 Methodische verantwoording 75 voorwoord Veel maatschappelijke en economische verschijnselen hebben een conjuncturele component: ze nemen in aantal, omvang of hevigheid toe en later weer af, en er is heel vaak sprake van daling op stijging en stijging op daling. Wie naar de Nederlandse mediasector kijkt, zal kunnen vaststellen dat het verkennen van de toekomst van de sector op dit ogenblik naar een hausse tendeert, spiegelbeeldig aan de baisse, aan de recessie die onze economie thans kenmerkt. Om alleen al enkele sectorverkenningen uit 2009 te noemen: de Hilversumse Media Academie presenteerde onder de titel Aristoteles Voorbij haar toekomstverkenning Medialandschap 2015, de Tijdelijke Commissie Innovatie en Toekomst Pers (de Commissie-Brinkman) schetste haar toekomstverwachtingen in De volgende editie, het Stimuleringsfonds voor de Pers sponsorde een studie van De Uitgeeffabriek met de titel Vormers en hervormers: toekomstbeeld voor printmedia, en in de eveneens door het Fonds gesubsidieerde verkenning Het persbureau in perspectief werden toekomstscenario’s voor persbureaus ontwikkeld. -

NOM Mediamerken 2017 - NOBO Merken

NOM Mediamerken 2017 - NOBO merken Samengesteld uit NOBO hoofdmerk Publisher submerken web app AD De Persgroep Nederland AD x x ADR Nieuwsmedia De Persgroep Nederland AD x x BN DeStem x x Brabants Dagblad x x de Gelderlander x x de Stentor x x Eindhovens Dagblad x x PZC x x Tubantia x x Autoweek Sanoma Media Autoweek x autoweek.nl x BeleggersBelangen ONE Business beleggersbelangen.nl x beurs.nl ONE Business Beurs.nl x m.Beurs.nl x Blogtoday Sanoma Media chantalbles.com x esthervuijsters.nl x googleusercontent.com x isntitdivine.com x jenniefromtheblog.com x me-to-we.nl x mynd.nu x shout-outtoyou.com x sillysilsil.com x stylehasnosize.com x wine-up.nl x yourlittleblackbook.me x BNR Nieuwsradio FD Mediagroep bnr.nl x Boekenkoopje Veen Media boekenkoopje.nl x Botenbank TMG botenbank.nl x Botentekoop TMG botentekoop.nl x Camperscaravans TMG camperscaravans.nl x Classic FM TMG classicfm.nl x Cosmopolitan Hearst Netherlands www.cosmopolitan.nl x Daskapital TMG daskapital.nl x dekrantvantoen NDC mediagroep dekrantvantoen.nl x Donaldduck Sanoma Media donaldduck.nl x Dumpert TMG dumpert-app x dumpert.nl x ELLE Hearst Netherlands www.elle.nl x ELLE Decoration Hearst Netherlands www.elle.nl x ELLE Eten Hearst Netherlands www.elleeten.nl x Elsevier Weekblad ONE Business elsevier.nl x Esquire Hearst Netherlands www.esquire.nl x Fashionchick Sanoma Media Fashionchick x fashionchick.nl x fashionista.nl x Fietsen123 Senior Publications Nederland fietsen123.nl x Filosofie Veen Media filosofie.nl x yellowmind.nl x Het Financieele Dagblad FD Mediagroep