Schrödinger Correspondence Applied to Crystals Arxiv:1812.06577V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes

Solid State Physics PHYS 40352 by Mike Godfrey Spring 2012 Last changed on May 22, 2017 ii Contents Preface v 1 Crystal structure 1 1.1 Lattice and basis . .1 1.1.1 Unit cells . .2 1.1.2 Crystal symmetry . .3 1.1.3 Two-dimensional lattices . .4 1.1.4 Three-dimensional lattices . .7 1.1.5 Some cubic crystal structures ................................ 10 1.2 X-ray crystallography . 11 1.2.1 Diffraction by a crystal . 11 1.2.2 The reciprocal lattice . 12 1.2.3 Reciprocal lattice vectors and lattice planes . 13 1.2.4 The Bragg construction . 14 1.2.5 Structure factor . 15 1.2.6 Further geometry of diffraction . 17 2 Electrons in crystals 19 2.1 Summary of free-electron theory, etc. 19 2.2 Electrons in a periodic potential . 19 2.2.1 Bloch’s theorem . 19 2.2.2 Brillouin zones . 21 2.2.3 Schrodinger’s¨ equation in k-space . 22 2.2.4 Weak periodic potential: Nearly-free electrons . 23 2.2.5 Metals and insulators . 25 2.2.6 Band overlap in a nearly-free-electron divalent metal . 26 2.2.7 Tight-binding method . 29 2.3 Semiclassical dynamics of Bloch electrons . 32 2.3.1 Electron velocities . 33 2.3.2 Motion in an applied field . 33 2.3.3 Effective mass of an electron . 34 2.4 Free-electron bands and crystal structure . 35 2.4.1 Construction of the reciprocal lattice for FCC . 35 2.4.2 Group IV elements: Jones theory . 36 2.4.3 Binding energy of metals . -

Bohr's Correspondence Principle

Bohr’s Correspondence Principle Bohr's theory was deliberately incomplete so that he could find principles that would allow a systematic search for a “rational generalization” of classical electrodynamics. A major conceptual tool that characterized Bohr’s atomic work was the correspondence principle, his celebrated asymptotic consistency requirement between quantum theory and classical physics, that took various forms over the years and was often misunderstood by even his closest collaborators [312, p. 114], but guided his research and dominated quantum theory until the emergence of quantum mechanics in 1925-26 [419, p. 81]. It should be emphasized that the correspondence principle is not the elementary recognition that the results of classical and quantum physics converge in the limit ℎ → 0. Bohr said emphatically that this [420] See the print edition of The Quantum Measurement Problem for quotation. Instead, the correspondence principle is deeper and aims at the heart of the differences between quantum and classical physics. Even more than the previous fundamental work of Planck and Einstein on the quantum, Bohr’s atomic work marked a decisive break with classical physics. This was primarily because from the second postulate of Bohr’s theory there can be no relation between the light frequency (or color of the light) and the period of the electron, and thus the theory differed in principle from the classical picture. This disturbed many physicists at the time since experiments had confirmed the classical relation between the period of the waves and the electric currents. However, Bohr was able to show that if one considers increasingly larger orbits characterized by quantum number n, two neighboring orbits will have periods that approach a common value. -

Higher Order Schrödinger Equations Rémi Carles, Emmanuel Moulay

Higher order Schrödinger equations Rémi Carles, Emmanuel Moulay To cite this version: Rémi Carles, Emmanuel Moulay. Higher order Schrödinger equations. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, IOP Publishing, 2012, 45 (39), pp.395304. 10.1088/1751- 8113/45/39/395304. hal-00776157 HAL Id: hal-00776157 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00776157 Submitted on 12 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. HIGHER ORDER SCHRODINGER¨ EQUATIONS REMI´ CARLES AND EMMANUEL MOULAY Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to provide higher order Schr¨odinger equations from a finite expansion approach. These equations converge toward the semi-relativistic equation for particles whose norm of their velocity vector c is below √2 and are able to take into account some relativistic effects with a certain accuracy in a sense that we define. So, it is possible to take into account some relativistic effects by using Schr¨odinger form equations, even if they cannot be considered as relativistic wave equations. 1. Introduction In quantum mechanics, the Schr¨odinger equation is a fundamental non-relativistic quantum equation that describes how the wave-function of a physical system evolves over time. -

Energy Bands in Crystals

Energy Bands in Crystals This chapter will apply quantum mechanics to a one dimensional, periodic lattice of potential wells which serves as an analogy to electrons interacting with the atoms of a crystal. We will show that as the number of wells becomes large, the allowed energy levels for the electron form nearly continuous energy bands separated by band gaps where no electron can be found. We thus have an interesting quantum system which exhibits many dual features of the quantum continuum and discrete spectrum. several tenths nm The energy band structure plays a crucial role in the theory of electron con- ductivity in the solid state and explains why materials can be classified as in- sulators, conductors and semiconductors. The energy band structure present in a semiconductor is a crucial ingredient in understanding how semiconductor devices work. Energy levels of “Molecules” By a “molecule” a quantum system consisting of a few periodic potential wells. We have already considered a two well molecular analogy in our discussions of the ammonia clock. 1 V -c sin(k(x-b)) V -c sin(k(x-b)) cosh βx sinhβ x V=0 V = 0 0 a b d 0 a b d k = 2 m E β= 2m(V-E) h h Recall for reasonably large hump potentials V , the two lowest lying states (a even ground state and odd first excited state) are very close in energy. As V →∞, both the ground and first excited state wave functions become completely isolated within a well with little wave function penetration into the classically forbidden central hump. -

Distortion Correction and Momentum Representation of Angle-Resolved

Distortion Correction and Momentum Representation of Angle-Resolved Photoemission Data Jonathan Adam Rosen 13.Sc., University of California at Santa Cruz, 2006 A THESIS SUBMIYI’ED 1N PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Physics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRETISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2008 © Jonathan Adam Rosen, 2008 Abstract Angle Resolve Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES) experiments provides a map of intensity as function of angles and electron kinetic energy to measure the many-body spectral function, but the raw data returned by standard apparatus is not ready for analysis. An image warping based distortion correction from slit array calibration is shown to provide the relevant information for construction of ARPES intensity as a function of electron momentum. A theory is developed to understand the calculation and uncertainty of the distortion corrected angle space data and the final momentum data. An experimental procedure for determination of the electron analyzer focal point is described and shown to be in good agreement with predictions. The electron analyzer at the Quantum Materials Laboratory at UBC is found to have a focal point at cryostat position 1.09mm within 1.00 mm, and the systematic error in the angle is found to be 0.2 degrees. The angular error is shown to be proportional to a functional form of systematic error in the final ARPES data that is highly momentum dependent. 11 Table .of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Tables v -

Difference Between Angular Momentum and Pseudoangular

Difference between angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum Simon Streib Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 516, SE-75120 Uppsala, Sweden (Dated: March 16, 2021) In condensed matter systems it is necessary to distinguish between the momentum of the con- stituents of the system and the pseudomomentum of quasiparticles. The same distinction is also valid for angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum. Based on Noether’s theorem, we demonstrate that the recently discussed orbital angular momenta of phonons and magnons are pseudoangular momenta. This conceptual difference is important for a proper understanding of the transfer of angular momentum in condensed matter systems, especially in spintronics applications. In 1915, Einstein, de Haas, and Barnett demonstrated experimentally that magnetism is fundamentally related to angular momentum. When changing the magnetiza- tion of a magnet, Einstein and de Haas observed that the magnet starts to rotate, implying a transfer of an- (a) gular momentum from the magnetization to the global rotation of the lattice [1], while Barnett observed the in- verse effect, magnetization by rotation [2]. A few years later in 1918, Emmy Noether showed that continuous (b) symmetries imply conservation laws [3], such as the con- servation of momentum and angular momentum, which links magnetism to the most fundamental symmetries of nature. Condensed matter systems support closely related con- Figure 1. (a) Invariance under rotations of the whole system servation laws: the conservation of the pseudomomentum implies conservation of angular momentum, while (b) invari- and pseudoangular momentum of quasiparticles, such as ance under rotations of fields with a fixed background implies magnons and phonons. -

SOLID STATE PHYSICS PART II Optical Properties of Solids

SOLID STATE PHYSICS PART II Optical Properties of Solids M. S. Dresselhaus 1 Contents 1 Review of Fundamental Relations for Optical Phenomena 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Optical Probes . 1 1.2 The Complex dielectric function and the complex optical conductivity . 2 1.3 Relation of Complex Dielectric Function to Observables . 4 1.4 Units for Frequency Measurements . 7 2 Drude Theory{Free Carrier Contribution to the Optical Properties 8 2.1 The Free Carrier Contribution . 8 2.2 Low Frequency Response: !¿ 1 . 10 ¿ 2.3 High Frequency Response; !¿ 1 . 11 À 2.4 The Plasma Frequency . 11 3 Interband Transitions 15 3.1 The Interband Transition Process . 15 3.1.1 Insulators . 19 3.1.2 Semiconductors . 19 3.1.3 Metals . 19 3.2 Form of the Hamiltonian in an Electromagnetic Field . 20 3.3 Relation between Momentum Matrix Elements and the E®ective Mass . 21 3.4 Spin-Orbit Interaction in Solids . 23 4 The Joint Density of States and Critical Points 27 4.1 The Joint Density of States . 27 4.2 Critical Points . 30 5 Absorption of Light in Solids 36 5.1 The Absorption Coe±cient . 36 5.2 Free Carrier Absorption in Semiconductors . 37 5.3 Free Carrier Absorption in Metals . 38 5.4 Direct Interband Transitions . 41 5.4.1 Temperature Dependence of Eg . 46 5.4.2 Dependence of Absorption Edge on Fermi Energy . 46 5.4.3 Dependence of Absorption Edge on Applied Electric Field . 47 5.5 Conservation of Crystal Momentum in Direct Optical Transitions . 47 5.6 Indirect Interband Transitions . -

Negative Mass in Contemporary Physics and Its Application to Propulsion Geoffrey A

Negative Mass in Contemporary Physics and its Application to Propulsion Geoffrey A. Landis, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 44135 6th Interstellar Symposium, Wichita KS, Nov. 10-15 2019. 6th Interstellar Symposium, Wichita, Kansas 2019 What do we mean by Mass? Physicists mean several different things when we refer to “mass” • Inertial mass F=mia 2 • Active (source) gravitational mass g=GMg/r *(more complicated in General Relativity) • Passive gravitational mass Fg=mgg 2 2 2 • Schrödinger mass ihdψ/dt=-(h /2ms)d ψ/dx +V *(or the corresponding term in Dirac or relativistic Schrödinger equation) 2 • Conserved mass/energy equivalent of mass: mo=E/c *(relativistic 4-vector) 2 • Quantum number m (e.g., me-= 511 MeV/c ) 6th Interstellar Symposium, Wichita, Kansas 2019 These terms are related by constitutive relations Inertial mass=gravitational mass Equivalence principle Active gravitational mass = Passive gravitational mass: Newton’s third law Schrödinger mass= inertial mass: correspondence principle Energy equivalent mass= inertial mass: special relativity Quantum number quantum indistinguishability 6th Interstellar Symposium, Wichita, Kansas 2019 Can mass ever be negative? • Einstein put “energy condition” into general relativity that energy must be positive. • E=Mc2; so positive energy = positive mass • Condition added to avoid “absurd” solutions to field equations • Many possible formulations: null, weak, strong, dominant energy condition; averaged null, weak, strong, dominant energy condition • Bondi pointed out that negative -

Schrödinger's Wave Equation

Schrödinger’s wave equation We now have a set of individual operators that can extract dynamical quantities of interest from the wave function, but how do we find the wave function in the first place? The free particle wave function was easy, but what about for a particle under the influence of a potential V(x,t)? Let us use the correspondence principle and classical physics to lead us to a general equation that dictates the form of the wave function, and thus tells us about the dynamics of the system. We know that the total energy for a (non- relativistic) particle is given by E = T +V. We now turn to the operators that we just discovered and replace the quantities in the energy equation by their respective operators: E = T + V ⇒ ∂ 2 ∂ 2 i = − h + V h ∂t 2m ∂x 2 This is an operator equation, and doesn’t really make much sense until we take it and operate on a wave function: 2 2 ∂Ψ()x,t h ∂ Ψ()x,t ih = − 2 + V ()x,t Ψ(x,t) ∂t 2m ∂x Of course, we really only get our expectation values of the quantities when we multiply (from the left) by Ψ* and integrate over all space. But, in order for that to give us reasonable quantities that describe the (quantum mechanical) motion of a particle, the wave function must obey this differential equation. This is Schrödinger’s Equation, and you will spend much of the rest of this semester finding solution to it, assuming different potentials. -

General Theoretical Description of Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy of Van Der Waals Structures

General theoretical description of angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy of van der Waals structures B. Amorim CeFEMA, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Rovisco Pais, 1049-001 Lisboa, Portugal∗ We develop a general theory to model the angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) of commensurate and incommensurate van der Waals (vdW) structures, formed by lattice mismatched and/or misaligned stacked layers of two-dimensional materials. The present theory is based on a tight-binding description of the structure and the concept of generalized umklapp processes, going beyond previous descriptions of ARPES in incommensurate vdW structures, which are based on con- tinuous, low-energy models, being limited to structures with small lattice mismatch/misalignment. As applications of the general formalism, we study the ARPES bands and constant energy maps for two structures: twisted bilayer graphene and twisted bilayer MoS2. The present theory should be useful in correctly interpreting experimental results of ARPES of vdW structures and other systems displaying competition between different periodicities, such as two-dimensional materials weakly coupled to a substrate and materials with density wave phases. I. INTRODUCTION defined, this picture might breakdown, as the ARPES re- sponse is weighted by matrix elements which describe the The development of fabrication techniques in recent light induced electronic transition from a crystal bound years enabled the creation of structures formed by state to a photoemitted electron state. For bands that stacked layers of different two-dimensional (2D) mate- are well decoupled from the remaining band structure, rials, referred to as van der Waals (vdW) structures [1– the ARPES matrix elements are featureless, and indeed 3]. -

Exploring Orbital Physics with Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy

Exploring Orbital Physics with Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy by Yue Cao B.S., Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2007 M.S., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics 2014 This thesis entitled: Exploring Orbital Physics with Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy written by Yue Cao has been approved for the Department of Physics Daniel S. Dessau Dmitry Reznik Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Cao, Yue (Ph.D., Physics) Exploring Orbital Physics with Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy Thesis directed by Prof. Daniel S. Dessau As an indispensable electronic degree of freedom, the orbital character dominates some of the key energy scales in the solid state | the electron hopping, Coulomb repulsion, crystal field splitting, and spin-orbit coupling. Recent years have witnessed the birth of a number of exotic phases of matter where orbital physics plays an essential role, e.g. topological insulators, spin- orbital coupled Mott insulators, orbital-ordered transition metal oxides, etc. However, a direct experimental exploration is lacking concerning how the orbital degree of freedom affects the ground state and low energy excitations in these systems. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) is an invaluable tool for observing the electronic structure, low-energy electron dynamics and in some cases, the orbital wavefunction. -

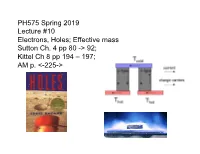

PH575 Spring 2019 Lecture #10 Electrons, Holes; Effective Mass Sutton Ch

PH575 Spring 2019 Lecture #10 Electrons, Holes; Effective mass Sutton Ch. 4 pp 80 -> 92; Kittel Ch 8 pp 194 – 197; AM p. <-225-> Thermal properties of Si (300K) 3# 2# ∆T 1# 0# !1# 0# 1# 2# 3# !2# !3# p!Si#<111># Vs !4# n!Si#<100># !5# Seebeck#Voltage#(mV)# Temperature#Difference#(K)# • p-type <111> Si • n-type <100> Si • p = 6.25×1018 cm-3 • n = 9.5 ×1017 cm-3 • ρ = 0.014 Ωcm • ρ = 0.021 Ωcm • S = + 652 µV K-1 • S = - 872 µV K-1 • κ = 148 W/mK • κ = 148 W/mK Rodney Snyder -3 2 2 -3 2 2 • PF = 3 x 10 V /K Wm • PF = 3 x 10 V /K Wm Dan Speer • ZT = 0.006 • ZT = 0.006 Josh Mutch Dispersion relation for a free electron, where k is the electron momentum: 2 k 2 E(k) = mass 2m Group velocity 2 −1 −1 ! 1 d E k $ ! d ( k + $ 1 dE(k) k p ( ) m # 2 2 & = # * - & = = = = v dk "dk ) m, % dk m m " % These are generalizable to the periodic solid where, now, k is NOT the individual electron momentum, but rather the quantity that appears in the Bloch relation. It is called the CRYSTAL MOMENTUM 1 −1 m* 2 2 E k v = ∇k E(k) = #"∇ k ( )%$ Problem on hwk Change in energy on application of electric field: δ E = qε ⋅vδt (F ⋅d) Change in energy with change in k on general grounds: δ E = ∇k E ⋅δk 1 v = ∇k E(k) d(k ) qε ⋅vδt = vk ⋅δk ⇒ qε = dt Get an equation of motion just like F = dp/dt ! hk/2π acts like momentum ….