Acts 28:16-31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Issues in Acts 28:11–31

Historical Issues in Acts 28:11–31 Gerd Lüdemann In this paper, I shall deal first with historical issues in Acts in general, and then turn my attention to a specific passage, namely Acts 28:11–31. I proceed in this way in the interest of transparency, because one’s overall approach to Acts nec- essarily determines how one deals with any specific section of it. Historical Issues in Acts Among other things, the author of Luke-Acts intends his work to be taken as historical reportage on early Christianity. The very first verse of Acts invokes the opening of his gospel, in which he claims to have critically evaluated all the available sources and goes so far as to attest the precision of the result. 1Since many have attempted to compose a narrative about the events which have come to fulfillment among us, 2as they have been handed down to us from those who from the beginning were themselves eyewitnesses and servants of the word, 3I too have thought it good, since I have investigated everything care- fully from the start, to write them out in order for you, excellent Theophilus, 4in order that you know the certain basis of the teaching in which you have been instructed. (Luke 1:1–4) This same introduction plainly refers to previous accounts—none of which he deems entirely precise—and promises what today might be called a new critical edition. The opening words of Acts constitute a virtual guarantee that the same intention and criteria guided his account of the spread of Christianity in his second book. -

The Conversion of Paul Acts 8:26-40

Acts 2:1-15 - The coming of the Holy Spirit Acts 3:1-10 - Peter heals a crippled beggar Acts 4:1-21 - The apostles are imprisoned Acts was written by a chap called Luke, yes the same guy who wrote Luke’s Gospel. In fact, Acts is kind of like a part 2, picking up the story where the Gospel ends. Acts 8:26-40 - Philip preaches to the Ethiopian We think Luke was a doctor – Paul calls him doctor in his letter to the Colossians and the way Luke describes some of the healings and other Acts 9:1-19 - The conversion of Paul events makes us think he was an educated man and most likely a doctor. Acts 9:19-25 - Paul in Damascus Our best guess is that it was written between AD63 and AD70 – that’s Acts 9:32-43 - Aeneas healed & Dorcas brought back to life more than 1,948 years ago. It was written not long after the events described in the book and about 30 years after Jesus died and was raised Acts 10:19-48 - Peter and Cornelius to life again. Acts 12:4-11 - Peter arrested and freed by an angel Luke himself tells us at the beginning of his Gospel that he wanted to write about everything that had happened – he was actually with Paul Acts 13:1-3 - Paul and Barnabas sent off on a few of his journeys. He says that the book is for Theophilus (easy for you to say!), we think he was a wealthy man, possibly a Roman Acts 14:8-18 - Paul heals the crippled man in Lystra official. -

This 28-Day Study

This devotional is meant to be a guide as you read through the book of Acts in 28 days. Read one chapter per day in the book of Acts and spend time with God using the devotions and questions provided. “However, I consider my life worth nothing to me; my only aim is to finish the race and complete the task the Lord Jesus has given me—the task of testifying to the good news of God’s grace.” - THE APOSTLE PAUL Acts 1: Let’s Go Crucified! Buried! Risen! Everything Jesus said has proven true! More than a good teacher, more than a wise friend, He is God of all! Fear evaporates and hope springs up as we encounter the risen Lord. Imagine the anticipation and excitement building among the first followers of Jesus as they wait together for the promised Holy Spirit. What an amazing time to be part of the Church! The promises and commands of Jesus resonate today just as they did over 2000 years ago. Acts 1:8 says, “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” The mission is not finished. God has called us and empowered us to take the gospel to the world. What an amazing time to be part of the Church! Are you ready for God to move in your family? Do you anticipate an amazing move of God in your workplace? Are you eager for God to change your community? The time for waiting is over. -

Acts 28 :28 – a Dispensational Boundary Line Otis Q

The Word of Truth Ministry Presents Special Full Length Studies #SS07 Acts 28 :28 – A Dispensational Boundary Line Otis Q. Sellers, Bible Teacher This pamphlet does not have to do with religion or religious systems. It is a treatise related to the interpretation, understanding and appreciation of the Word of God. It does not deal with service for God. It deals with the truth of God. The writer sincerely believes that the truth presented in this study is a key that unlocks much of the New Testament. Experience has demonstrated to him that the recognition of Paul's declaration in Acts 28:28 as a dispensational dividing line will provide answers to Biblical questions that have long seemed unanswerable, solutions to problems that have seemed insoluble, that it will clear away what heretofore have been insuperable difficulties, and provide honest explanations of contradictions that have puzzled students of Scripture down through the centuries. An ever deepening conviction has come to him that the full acceptance of the principle of interpretation set forth in these pages will permit the student of the Word of God to feel assured that he has fully obeyed the divine command set forth by Paul to Timothy: Study to show thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth. 2 Timothy 2:15. Furthermore, it is his conviction that the full acceptance of this principle by a sufficient number of faithful men would bring about a sorely needed revival of interest in the Word of God, opening up as it does new avenues of Bible study into truths of Scripture which have baffled many who have tried to explore them. -

Commentary on Acts 28:16-31 by L.G. Parkhurst, Jr

Commentary on Acts 28:16-31 By L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson ( Uniform Series ) for August 29, 2010 , is from Acts 28:16-25, 28-31 ; however, to maintain the context, the commentary below is on Acts 28:16-31 . Five Questions for Discussion follow the Bible Lesson Commentary. These are my preliminary verse by verse study notes before writing my Bible Lesson for The Oklahoman newspaper. They may help you in your class preparation and discussion. I do encourage you to write your own verse by verse notes and questions before reading the notes and questions below. 16 When we came into Rome, Paul was allowed to live by himself, with the soldier who was guarding him. In this imprisonment, Paul was in a home that he had to provide for himself, not behind bars or in a dungeon but in house arrest. A guard stayed with Paul at all times, and probably restricted Paul’s movements. This type of imprisonment may have been a courtesy, because Paul had no charges against him for breaking any Roman laws, and Paul was a Roman citizen. He was imprisoned because he appealed to the emperor to save himself from the Jews who had plotted to kill him in Jerusalem or on the road. 17 Three days later he called together the local leaders of the Jews. When they had assembled, he said to them, “Brothers, though I had done nothing against our people or the customs of our ancestors, yet I was arrested in Jerusalem and handed over to the Romans. -

Acts 28:16-31

a Grace Notes course The Acts of the Apostles an expositional study by Warren Doud Lesson 410: Acts 28:16-31 Grace Notes 1705 Aggie Lane, Austin, Texas 78757 Email: [email protected] ACTS ACTS410 - Acts 28:16-31 Contents ACTS 28:16-31................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Rome in Bible Times .................................................................................................................................................. 12 The Praetorian Guard .................................................................................................................................................. 14 Paul’s Journey to Rome ............................................................................................................................................... 14 The Acts of the Apostles Page 3 ACTS 410: Acts 28:16-31 a Grace Notes study ACTS 28:16-31 and was settled in it, and was rested from the fatigue of his voyage and journey: ACTS 28:16. And when we came to Rome, To the city itself: Paul called the chief of the Jews together: he sent to the principal men among them; for the centurion delivered the prisoners to the though the Jews, were expelled from Rome in captain of the guard; or general of the army; the reign of Claudius, they were now returned, or, as some think, the governor of the and had their liberty of residing there; very “praetorian” band of soldiers, who attended the likely by means -

Acts 28 Teaching Outline

Acts 28 - Unfinished Stacy Davis - www.delightinginthelord.com May 11, 2017 Acts 27:42-28:6 - Unfinished Faith Malta - “refuge” - small island 20 miles long, 60 miles from Sicily. Paul stays here 3 months God has a plan and God finishes what He starts Creation - Genesis 2:1 God enables, empowers and directs His servants to help Him finish Moses - tabernacle (Exodus 39:32) & writing of the law (Deut. 31:24) Solomon - house of the Lord (1 Chronicles 28:20; 2 Chronicles 8:16) Nehemiah - wall around temple (Nehemiah 6:15) God’s Redeemed Through Jesus John 4:34, John 17:4, John 19:30 God Works in each of us through the Holy Spirit: Philippians 1:6 Complete: epiteleo - bring to an end, execute, perfect -Satan tries to hinder God’s plan from being completed - Snake fastened to Paul. Paul shakes it off looking to Jesus. Hebrews 12:2 “Looking unto Jesus, the author and the finisher of our faith, who for the joy that was set before Him endured the cross, despising the shame, and has sat down at the right hand of the throne of God.” Finisher: teleiotes - Jesus is the teleiotes of our faith, the ultimate example accomplishing with the end in view - a process Acts 28:7-10 - Unfinished Ministry Paul heals Publius’ father and many others Acts 28:11-16 - Unfinished Journey Paul travels to 3 more cities before finally “coming to Rome” Psalm 27:14 “Wait on the Lord, be of good courage, and He shall strengthen your heart, wait, I say, on the Lord.” Acts 28:17-29 - Unfinished Salvation for the Jews and Gentiles v. -

The Tuesday Afternoon Bible Study - Acts 28 Ashore on Malta, Arrival in Rome

The Tuesday Afternoon Bible Study - Acts 28 Ashore on Malta, Arrival in Rome Can you believe it that we’ve made it to the end of Acts? When we started back in January, did you think we’d ever get here? And we certainly couldn’t imagine the pandemic which we would enter into, and how it would turn our lives upside down. We’ve been on our own dangerous journey! Last week we left Paul and his 275 companions sputtering ashore on some unknown island - weak, wet, but alive after being trapped on the Mediterranean Sea by a hurricane for over 2 weeks. They will discover they have landed on Malta, which is about 60 miles south of Sicily, Italy. Read Acts 28: 1-10 Safely Ashore on Malta 1. Luke writes that the natives of Malta (called Maltese, like the falcon) shown them unusual kindness. When has a stranger been kind to you? When have you offered kindness to a stranger? 2. Paul gets bit by a snake, a viper. I don’t want to know if a snake has ever bitten you. I don’t like snakes at all. Note the local logic: If God allows you to escape one catastrophe only to die in another, well, then you must be guilty after all. 3. But when Paul doesn’t die… well then, he must be a god, they reason. Quite a turnaround. 4. Paul is able to repay their kindness by healing the father of the island’s “leading man.” And once they find out Paul has this gift from God, the line forms. -

Love God – Bible Reading Acts 28-Day Reading Guide

Love God – Bible Reading To make the Bible reading plans as accessible as possible, we have provided them in a variety of formats. These plans come from www.bible.com (also in the YouVersion app) and are designed to be accessed on your smart phone, computer or tablet with links to both the scripture reading and the devotional content. Acts 28-Day Reading Guide This reading guide was written by NewSpring staff and volunteers to guide you through the book of Acts in 28 days. Read one chapter each day and spend time with God using the devotionals and questions provided. Source: https://www.bible.com/en-GB/reading-plans/864 This is a 28-day reading plan. Seven days of it will be sent out each week. DAY 22 Bible Reading: Acts 22 Devotional There are few things more powerful and disarming than a story, particularly the story of how Jesus changed someone’s life. Paul could have argued the finer points of the law with anyone in the crowd. He could have expounded on Christ’s fulfillment of every nook and cranny of Old Testament prophecy. Instead, he shared his story of transformation with a vicious mob. A murderer of Christians morphed into a preacher of the gospel—that’s compelling stuff! Every Christ follower has a story to tell. All of us have been rescued from a life of sin and disobedience, set free to follow Jesus. God does not call us to be articulate salesmen or well-educated theologians. He has equipped us better than that. -

Acts 28 Day Guide

ACTS A 28-Day Guide to Spiritual Formation & Discipleship “In the space of one generation, a little company of Jesus’ disciples with explosive force sweeps from Jerusalem to Rome and develops from a small sect into a universal church. Nothing can defeat them - not the beatings of swaggering tyrants; not the cunning of embittered religious rulers, not the internal struggles of discontented members - but like a mighty army with banners, they move out to disciple the nations in the name of their risen and reigning Lord.” Robert E. Coleman The Master Plan of Discipleship P. 02 HOW TO TRACK WITH A Catalog | Lookbook A Catalog ACTS STUDY 1 28-DAY DEVOTIONAL ON YOUR OWN TO TAKE YOU THROUGH THE ENTIRE BOOK OF ACTS 2 30 MINUTE TEACHING EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT AT 7PM ON THE BE HOPE CHURCH ONLY GROUP TO GIVE A GRASP OF THE BOOK OF ACTS AND KEY THEMES 3 DEVOTIONALS EVERY TUESDAY & THURSDAY ON FACEBOOK LIVE 4 DISCUSSIONS WITH YOUR TEAM HOW TO TRACK WITH US 1 JOIN THE BE HOPE CHURCH FAMILY FACEBOOK GROUP 2 GO TO BEHOPE.CHURCH/ACTS FOR AN ONLINE VERSION OF THIS INFORMATION P/42 Contents NEW LIVING TRANSLATION ACTS STUDY www.livy-living.com Day 1 | Acts 1:1-26 6-7 Day 15 | Acts 15:1-41 40-42 Day 2 | Acts 2:1-47 8-9 Day 16 | Acts 16:1-40 43-45 Day 3 | Acts 3:1-24 10-11 Day 17 | Acts 17:1-34 46-47 Day 4 | Acts 4:1-36 12-13 Day 18 | Acts 18: 1-28 48-49 Day 5 | Acts 5:1-41 14-15 Day 19 | Acts 19:1-41 50-51 Day 6 | Acts 6:1-15 16 -17 Day 20 | Acts 20:1-38 52-53 Day 7 | Acts 7:1-60 18-21 Day 21 | Acts 21:1-40 54-55 Day 8 | Acts 1-40 22-23 Day 22 | Acts 22:1-30 57-59 Day 9 | Acts 9:1-42 24-26 Day 23 | Acts 23:1-35 60-61 Day 10 | Acts 10:1-48 27-29 Day 24 | Acts 24:1-27 62-63 Day 11 | Acts 11:1-30 30-31 Day 25 | Acts 25:1-27 64-65 Day 12 | Acts 12:1-25 32-33 Day 26 | Acts 26:1-32 66-67 Day 13 | Acts 13:1-52 34-37 Day 27 | Acts 27:1-44 68-69 US Day 14 | Acts 14:38-39 38-39 Day 28 | Acts 28:1-31 70-71 Lecture & Discussion Group Notes 72-79 P. -

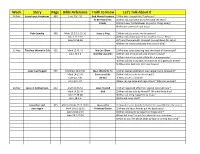

Family Devotions Schedule Spring 2021

Week Story Page Bible Reference Truth to Know Let's Talk About It 14-Mar Jesus Loves Zacchaeus 403 Luke 19:1-10 God Wants Everyone 1)Why didn't people like Zacchaeus? to Be Part of His 2)What did Zacchaeus do so he could see Jesus? Family 3)Was it easy for Zacchaeus to give his things away? 4)Who can come to know Jesus? Palm Sunday 409 Matt. 21:1-11, 15-16 Jesus is King 1)What did Jesus ride into Jerusalem? Mark 11:1-10 2)What did people put on the road for Jesus? Why? Luke 19:28-38 3)If I was there would I have put my coat down for Jesus? 4)What can I do to celebrate that Jesus is King? 21-Mar The Poor Woman's Gift 415 Mark 12:41-44 We Can Show 1)Who was Jesus watching near the doors of the temple? Luke 21:1-4 God We Love Him 2)What kind of noise did a lot of money make? 3)What kind of noise did a little bit of money make? 4)What did Jesus say about the woman who gave just a little? 5) What does God look for in our hearts? Jesus' Last Supper 419 Matthew 26:17-30 Jesus Wants Us To 1)What special celebration was happening in Jerusalem? Mark 14:12-26 Serve Just Like 2)What did Jesus do for His friends? Luke 22:7-20 He Did 3) Why did Jesus do that? John 13:1-17 4)How can we serve and help others? Who can we help? 28-Mar Jesus in Gethsemane 422 Matt 26:36-50 Jesus Trusted 1)What happened after their special Passover meal? Mark 14:32-46 God 2)What did Jesus do by Himself? Who did He talk to? Luke 22:39-48 3)What sad thing happened to Jesus? John 18:1-9 4)Who did Jesus trust? Jesus Dies and 425 Matt 26:58-68, 27:11-28:10 Jesus is the 1) How -

Paul Is Arrested at Jerusalem

Acts Lesson 28 ➣ Paul Arrested at Jerusalem, 57AD ➣ Acts 21:1–22:1 Paul approaches Jerusalem ▼The course to Jerusalem Acts 21:1 After we had torn ourselves away from them, we put out to sea and sailed straight to Cos. The next day we went to Rhodes and from there to Patara. 2 We found a ship crossing over to Phoenicia, went on board and set sail. 3 After sighting Cyprus and passing to the south of it, we sailed on to Syria. We landed at Tyre, where our ship was to unload its cargo. ▼The cautions from Christian comrades about Jerusalem The disciples at Tyre and Ptolemais Acts 21:4 Finding the disciples there, we stayed with them seven days. Through the Spirit they urged Paul not to go on to Jerusalem. 5 But when our time was up, we left and continued on our way. All the disciples and their wives and children accompanied us out of the city, and there on the beach we knelt to pray. 6 After saying good-by to each other, we went aboard the ship, and they returned home. 7 We continued our voyage from Tyre and landed at Ptolemais, where we greeted the brothers and stayed with them for a day. Philip and Agabus at Caesarea Acts 21:8 Leaving the next day, we reached Caesarea and stayed at the house of Philip the evangelist, one of the Seven. 9 He had four unmarried daughters who prophesied. 10 After we had been there a number of days, a prophet named Agabus came down from Judea.