Marikanave Report 2021 Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

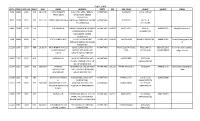

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Geographical Features of Karnataka

Class : B.A 5th Semester Subject : History & Archaeology Title of the Paper : History and Culture of Karnataka(From Early Times to 1336) Paper II Optional Session: 7,8 & 9. Topic : Geographical Features of Karnataka. __________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Karnataka State is situated in between 11.30 to 18.48 Northern latitude and 74.12 to 78.50 East longitude, Karnataka is surrounded by Maharashtra in North, Goa in Northwest, Tamilnadu & Keral in South, Andhara Pradesh & Telengana in East. Karnataka is 2000 feet above sea level. Present Karnataka is divided in to 30 Districts 230 Talukas 29733 Villages. The length of the state is 770 km and breadth is 400 km total extent of the State is 1,92,204 sq. km The main rivers of Karnataka is Krishna, Bhima, Tungabhadra, Malaprabha, Ghatprabha, Kali, Sharavati, Varadha, Kaveri, Netravati, Arkavati, Aghanashini etc. are the important rivers in the State. The region where two rivers joins is called as Doab. Shorapur Doab in Yadgiri district where river Bhima joins the Krishna. Raichur Doab where river Tungabhadra joins Krishna, the plateau of Raichur Doab & Tungabhdra referred as Rayalaseema. Geographical Classification of Karnataka 1. Coastal region 2. Sahyadri Mountains /Western Ghats 3. Northern Plain 4. Southern Plain Importance of Geographical Features : Richard Hakluyat, pointed out that “The Geography & Chronology are the Sun & Moon, the right and left eye of History”. Human history in a region is shaped by the physical features. The growth of civilization is depend upon the climate, fertility of soil, natural barriers. Geographically Karnataka is one of the oldest part of Deccan plateau. The history and culture of Karnataka has been molded by the Geographical features. -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

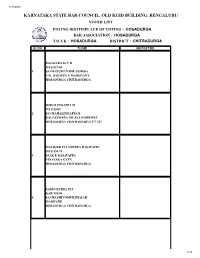

Voter List Poling Booth/Place of Voting: Hosadurga

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : HOSADURGA BAR ASSOCIATION : HOSADURGA TALUK : HOSADURGA DISTRICT : CHITRADURGA SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE BASAVARAJA T H MYS/327/68 1 S/O HANUMANTHE GOWDA C/O. BASAPPA E MAREHANT HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA SHIVALINGAPPA M MYS/35/69 2 S/O MAHALINGAPPA B KALLESWARA NILAYA KOBRIPET HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 577 527 MALIGER PALANETRA BASAVAPPA MYS/330/74 3 S/O K.P. BASAVAPPA VINAYAKA EXTN HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA SADYOJATHA M S KAR/159/80 4 S/O MS SHIVOMURTHAIAH MADHURE HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 1/15 3/17/2018 SHADAKSHARAPPA H.R. KAR/380/80 5 S/O RAMALINGAGOWDA H T AT PO: HEGGONE HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA KALMAT S S KAR/168/82 6 S/O SIDDAIAH KALMAT SIDDESHWARA EXTN HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 577527 PARANNA K M KAR/375/83 S/O MARULAIAH 7 NO 376, AYYAPPA SWAMY EXTENSION, H.H ROAD HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 560 010 BOMMANNA A L KAR/497/84 S/O PATEL LINGAPPA 8 DOOR 155/1, 2ND MANIN, 2ND CROSS, NIDHYA NAGARA HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA BASAVARAJAPPA C KAR/604/84 S/O G S CHIKKAVEERAPPA 9 SADGURU ASHIRAM ROAD, VIJAYA NAGARA EXTENTION HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 2/15 3/17/2018 SRINIVASA.S. KAR/808/85 S/O SUBBANNAIAH B 10 SAPTHAGIRI GIRIJAMMA LAYOUT ,NEAR GANDHI CIRCLE , TOWN HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 577 527 B J BHARATHA. KAR/270/89 11 S/O JANARDHANA NAIDU BALLALA SAMUDRA POST HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA NAGARAJA K.V. KAR/40/90 12 S/O K M VIRUPAKSHAPPA KITTADAL, CHITHRADURGA HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 560 076 BASAVARAJU C. KAR/508/91 S/O CHOKKALINGAPPA 13 PRAKRUTHI SADANA , IST MAIN , IIND CROSS , VIDYANAGARA HOSADURGA CHITRADURGA 577 554 RUKMINI H.S. -

Language Handbook, Tumkur

MYSORE CENSUS 1951 LANGUAGE HANDBOOK TUMKUR DISTRICT J. B. MALLARAU>HY A Published for the Government of India by the Manager of Publications and Printed at the Government Press, Bangalore by the Director of Printing in Myson~ 19~~ TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY LANGUAGE PATTERN OF TUMKUR DISTRICT III STATEMENT SHOWING DIFl!'ERENCES BETWEEN THE ORIGINAL AND PRESENT SORTINGS IV TABLES Madhugiri Taluk 1 Koratagere Taluk 9 Sira Taluk 15 Pavagada Taluk 21 FACING PAGE LANGUAGE MAPS Tumkur District III Madhugiri Taluk 1 Koratagere Taluk ,9 Sira Taluk 15 Pavagada Taluk 21 INtRODUCTORY Towards the end of August 1953, the Government of Mysore asked me to undertake tbe extmction of figures relating to Scheduled Castes and S,0heduled Tribes, for submission of circle wise statements to the Delimitation Commission. Just when the work was about to be taken on hand accordingly, the Prime Minister happened to announce in Parliament that a High Power Commission was shortly to be appointed to go into the question of reorganisation of States. Since this meant that sooner or later there would be a demand for village wise language data, at least in respect of bilingual areas· in the State, I sought the permission of the Deputy Regis trar General to extract the language figures simultaneously with the extraction of figures for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. rrhe Deputy Registrar Genera.!, India, readily fell in with my view but suggested that the extraction of villagewise language data, be confined only to taluks lying' on either side of a lingui8tic dividing line.' Accordingly, figures ,\'ere extracted for the villages of the following 13 clearly bilingual taluks :-- BANGALOltE DISTRICT TUMKUR DISTRICT KOLAIt DIS~RIC~' CHITALDRUG DIS'rRW'l' Hoskote Pavagada MaIm Challakere Devanhalli Koratagere Kolllr Anekal Madhugiri Goribidnur DodballapUI' Chikballapur Sidlllghatta With villagewise language data cmnpiled for the above taluks, I thought I had anticipated all pos8ible demands. -

Hiriyur Taluk, Chitradurga District,Karnataka

Draft Report क� द्र�यभू�म �ल बो जल संसाधन, नद� �वकास और गंगा संर�ण मंत्रा भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Hiriyur Taluk, Chitradurga District,Karnataka द��ण पि�चमी �ेत, ब�गलोर South Western Region,Bengaluru FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY No. Naquim-Taluk-17 /2016-17 Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Central Ground Water Board HIRIYUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLANS, CHITRADURGA DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE By L.J.BALACHANDRA Scientist ‘D’ Central Ground Water Board South Western Region Bangalore March 2017 HIRIYUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLANS, CHITRADURGA DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE CONTENTS Sl. No. Chapter Page No. Title 1 SALIENT INFORMATION 1 2 AQUIFER DISPOSITION 7 GROUND WATER RESOURCE, EXTRACTION, 9 3 CONTAMINATION AND OTHER ISSUES 4 GROUND WATER RESOURCE ENHANCEMENT 12 5 DEMAND SIDE INTERVENT IONS 14 HIRIYUR TALUK AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLANS, CHITRADURGA DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE 1. SALIENT FEATURES Name of the taluk : HIRIYUR District : Chitradurga State : Karnataka Area : 1,717 sq.km. Population : 2,86,494 Annual Normal Rainfall : 593 mm Hiriyur taluk, Chitradurga district, Karnataka state covering an area of 1717 Sq. Kms and is a part of Krishna river basin located at longitudes 13 0 40’ 59” : 140 12’ 12” and east latitude of 760 26’ 6.7” : 760 57’15.5” falling in survey of india toposheet numbers 57 C/9, C/10 and 57 B/12 and B/16 and is bounded by Chitradurga and Chellakere taluks of Chitradurga district in the North, Tumkur district in the South, Holalkere and Hosadurga taluks of chitradurga district in west and in the East it is bounded by Andrapradesh. -

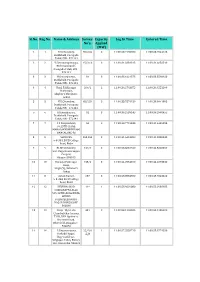

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey No's. Capacity Applied (MW

Sl.No. Reg.No. Name & Address Survey Capacity Log In Time Entered Time No's. Applied (MW) 1 1 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:23.7195700 11:00:23.7544125 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 2 2 Y.Satyanarayanappa, 15/2,16 3 11:00:31.3381315 11:00:31.6656510 Bheemunikunte, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 3 3 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:33.1021575 11:00:33.5590920 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 4 4 Hanji Fakkirappa 209/2 2 11:00:36.2763875 11:00:36.4551190 Mariyappa, Shigli(V), Shirahatti, Gadag 5 5 H.V.Chowdary, 65/2,84 3 11:00:38.7876150 11:00:39.0641995 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 6 6 H.Ramanjaneya, 81 3 11:00:39.2539145 11:00:39.2998455 Doddahalli, Pavagada Taluk, PIN - 572141 7 7 C S Nanjundaiah, 56 2 11:00:40.7716345 11:00:41.4406295 #6,15TH CROSS, MAHALAKHSMIPURAM, BANGALORE-86 8 8 SRINIVAS, 263,264 3 11:00:41.6413280 11:00:41.8300445 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 9 9 BLDE University, 139/1 3 11:00:23.8031920 11:00:42.5020350 Smt. Bagaramma Sajjan Campus, Bijapur-586103 10 10 Basappa Fakirappa 155/2 3 11:00:44.2554010 11:00:44.2873530 Hanji, Shigli (V), Shirahatti Gadag 11 11 Ashok Kumar, 287 3 11:00:48.8584860 11:00:48.9543420 9-8-384, B.V.B College Road, Bidar 12 12 DEVUBAI W/O 11* 1 11:00:53.9029080 11:00:55.2938185 SHARANAPPA ALLE, 549 12TH CROSS IDEAL HOMES RAJARAJESHWARI NAGAR BANGALORE 560098 13 13 Girija W/o Late 481 2 11:00:58.1295585 11:00:58.1285600 ChandraSekar kamma, T105, DNA Opulence, Borewell Road, Whitefield, Bangalore - 560066 14 14 P.Satyanarayana, 22/*/A 1 11:00:57.2558710 11:00:58.8774350 Seshadri Nagar, ¤ltĔ Bagewadi Post, Siriguppa Taluq, Bellary Dist, Karnataka-583121 Sl.No. -

Capsule for Rrb Po/Asst & Niacl (Mains)

aa Is Now In CHENNAI | MADURAI | TRICHY | SALEM | COIMBATORE | CHANDIGARH | BANGALORE |ERODE | NAMAKKAL | PUDUCHERRY |THANJAVUR |TRIVANDRUM | ERNAKULAM |TIRUNELVELI |VELLORE | www.raceinstitute.in | www.bankersdaily.in CAPSULE FOR RRB PO/ASST & NIACL (MAINS). GENERAL AWARENESS & STATIC GK Exclusively prepared for RACE students Chennai: #1, South Usman Road, T Nagar. | Madurai: #24/21, Near MapillaiVinayagar Theatre, Kalavasal. | Trichy: opp BSNL office, Juman Center, 43 Promenade Road, Cantonment. | Salem: #209, Sonia Plaza / Muthu Complex, Junction Main Rd, State Bank Colony, Salem. | Coimbatore #545, 1st floor, Adjacent to SBI (DB Road Branch),DiwanBahadur Road, RS Puram, Coimbatore| Chandigarh| Bangalore|Erode |Namakkal |Puducherry |Thanjavur| Trivandrum| Ernakulam|Tirunelveli | Vellore | H.O: 7601808080 / 9043303030 | www.raceinstitute.in Chennai RACE Coaching Institute Pvt Ltd CAPSULE FOR RRB PO/ASST & NIACL (MAINS) BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS RESERVE BANK OF INDIA (RBI) Third Bi-Monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2018-19: Resolution of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC): Reserve Bank of India Policy Rate Current Rate Previous Rate Repo Rate 6.50% 6. 25% Reverse Repo Rate 6.25% 6. 00% Marginal Standing 6.75% 6. 50% Facility Rate Bank Rate 6.75% 6. 50% CRR 4% (Unchanged) 4% SLR 19. 5% 19. 5% (Unchanged) ➢ The six-member monetary policy committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has decided to increase the repo rate by 25 basis points to 6.5% due to inflation concerns. ➢ According to the RBI Annual Report, it was mentioned due to the evolving economic conditions, real GDP growth for 2018-19 is expected to increase to 7.4% from 6.7% in the previous year. -

To Download GK/GA Capsule for IBPS Clerk & RRB

ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series BEST ONLINE TEST SERIES SITE FOR PARA 13.2 , III EXAM, GIPSA OFFICER SCALE 1-5 1 ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series RRB & IBPS Clerk Mains Exam GK Capsule (Covered August 2020 to Jan 2021) Index No. of Chapter Topics Name Chapter 1 Important Appointment (National, International) Chapter 2 Awards (National, International) Chapter 3 Government Scheme/ campaign Chapter 4 Summit/ Conference Chapter 5 Ranking Index Chapter 6 Partnership/ Agreement Chapter 7 loans agreement for India from different organizations Chapter 8 Mergers and Acquires Chapter 9 APP/Website/Card Chapter 10 India’s GDP Forecast FY21 &22 (Last Update 5th Feb 2021) Chapter 11 Budget 2020 & Atma Nirbhar Package Chapter 12 Important Committee Chapter 13 Banking & Financial Chapter 14 Current Affairs (National) In Short Chapter 15 Current Affairs (International) In Short Chapter 16 Defence News Chapter 17 Sports News BEST ONLINE TEST SERIES SITE FOR PARA 13.2 , III EXAM, GIPSA OFFICER SCALE 1-5 2 ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series Chapter 18 Upcoming Sports Events & Venues Chapter 19 List of Important Book and Author 2020 Chapter 20 Important Day and Theme 2020 Chapter 21 Obituary Chapter 22 Science related News Chapter 23 Banks Name & CEO of Bank & Headquarter & Tagline Chapter 24 State Chief Ministers and Governors Chapter 25 Cabinet ministers of India with their constituency Chapter 26 List of Union Ministry Secretary Static No. of Chapter Topics Name (Page No. 188 to 227) Chapter 1 Dams in India Chapter 2 Folk Dance Chapter 3 List -

Village Defenses of the Karnataka Maidan, AD 1600-1800

Village Defenses of the Karnataka Maidan, AD 1600-1800 BARRY LEWIS Introduction understood fully unless considered in cultural context as part of related larger issues of village design. And, if one The Nayaka period in Karnataka roughly brackets the understands the basics of village design, the way is open centuries between the fall of Rama Raya's capital city of to understanding aspects of Nayaka period town and city Vijayanagara in 1565 and the fall of Tipu Sultan's capital design and how communities generally coped with the of Srirangapatna in 1799. The former effectively broke trying conditions of these centuries. the back of the Vijayanagara empire in Karnataka and the Several other practical reasons also motivate the latter left the British as the major political force in South present focus on village defensive features. Firstly, as with India.' In the turbulent centuries between these events, the many other aspects of historical research on the lives of Mughals, the Marathas, the Mysore sultans, the Nizam, common people, studies of South Indian military features the British, the French, and scores of smaller rulers and and landscapes seldom address village-level .security chiefs fought for control of much of South India. As if to concerns.'' The result promotes the unwarranted impression make things worse, marauders roamed the countryside that defense was primarily the province of elites, and, if plundering what was left, and villages preyed on each other it were widespread throughout society, it was of little when conditions -

Brief Note on Upper Bhadra Project

BRIEF NOTE ON UPPER BHADRA PROJECT Upper Bhadra Project is a major lift irrigation Scheme under implementation in the central region of Karnataka State. It envisages lifting upto17.40 TMC of water in first stage from Tunga river to existing Bhadra reservoir and lifting 29.90 TMC of water in second stage from Bhadra reservoir to Tunnel near Ajjampura, in Tungabhadra sub-basin of Krishna basin. After Tunnel, it is planned to irrigate an extent of 2,25,515 ha by micro irrigation in districts of Chikmagalur, Chitradurga, Tumkur and Davangere. The primary objective of the project is providing sustainable irrigation facility in khariff season and the other objective of the project is to recharge the ground water table and provide drinking water by filling 367 tanks in drought-prone taluks of the above said districts. Taluka-wise Area Benefited under Upper Bhadra Project (comprehensive) Area for Irrigation (Ha) Total Area Tank SL Tumkur Jagalur for District Taluk Tarikere Chitradurga filling No Branch Branch Irrigation Lift Branch Canal (Nos) Canal Canal (Ha) Chika- Tarikere 20150 411 1628 - 22189 81 1 magalur Kadur - 1864 20502 - 22366 32 Hosadurga - 31035 13573 - 44608 27 Holalkere - 371 - - 371 21 Hiriyur - 37052 29982 - 67034 32 2 Chitradurga Chitradurga - 23266 - 5700 28966 08 Challakere - 13266 - - 13266 51 Molkalmuru - - - - 20 C.N Halli - - 4657 - 4657 19 3 Tumkur Sira - - 14558 - 14558 41 Pavagada - - - - - 30 4 Davanagere Jagalur - - - 7500 7500 05 Total 20150 107265 84900 13200 225515 367 Background : The areas of Chitradurga, Tumkur and part of Davanagere districts are affected by chronic droughts. There are no major projects constructed in these areas except Hemavati Project which is providing irrigation facilities to part of Tumkur district & Bhadra Project to parts of Davanagere district. -

K S C Apex Bank Ltd., Bengaluru

K S C APEX BANK LTD., BENGALURU - 560018 LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES FOR INTERVIEW FOR THE POST OF CLERK-CUM-CASHIER NAME SL ROLL & NO NO ADDRESS 1 1239 VIDYASAGAR S/O KARANAPPA GOUDA AT - KELLUR, TALUKA - JEWARGI, DIST - GULBARGA, PIN - 585303 2 2005 BASAVARAJ K S/O CHANNABASAPPA K, AT - VENKATESHWARA CAMP, POST - GANDHINAGAR, TALUKA - SINDHANURU, DIST - RAICHUR - 584128 3 230 MALLIKARJUN DONI S/O GORABANATH DONI, AT POST - KADAGANCHI, TALUKA - ALAND, DIST - KALABURGI, PIN - 585311 4 1278 BHEEMANNA S/O PIDDAPPA, AT - MACHAGUNDAL, POST, DEVAR GONAL, TALUKA - SURAPUR, DIST - YADAGIRI, PIN - 585220 5 1150 SHANTHAMALLAPPA S/O CHANDRA SHEKAR, AT POST - KADANI, TALUKA AND DIST - KALABURGI - 585308 6 452 PAVITRA MURAL MALLANNA D/O MALLANNA, RAJANAKOLLUR, SHURAPUR TQ., YADAGIRI DIST-585291 7 1413 PRIYANKA D/O VISHWANATH, VIDYANAGARA COLONY, 5TH CROSS, H NO.#9-12-568/537, BIDAR - 585403 8 1350 DEEPTI C D/O CHANDRASHEKAR C NO.2A, 2ND CROSS, RAMAMURTHY NAGARA CHURCH, DOORAVANI NAGAR POST, BANGALORE - 560016 9 1242 DEEPIKA D/O BASAVARAJ KAMSHETTY H-NO-1-5-21, DARZIL GALLI, BIDAR - 585401 10 921 SUMAN HALKAR D/O BASAWARAJ HALKAR PLOT NO.46, POOJA TAILORS, OM NAGAR, SEDAM ROAD, GULBARGA - 585105 11 1345 HARISHA S/O SHARANAPPA, SDC - KARNATAKA HIGH COURT, KALABURAGI PEETH, KALABURAGI - 585107 12 692 VANARAJ S/O SUGAPPA METI, AT POST - MUSHTAHALLI, POST - SELLAGI, TALUKA - SURPUR, DIST - YADAGIR - 585224 13 981 THIMMAPPA H S/O YANKANNA H, UPPARA HOSAHALLI POST, SIRAGUPPA TALUKA, BELLARY DIST, PIN - 583122 14 903 MANJUNATHA S G S/O SHIVALINGAPPA HAVINAHALU