Looking for the Blind Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![A History of the Zombie Film [To the Mid 1990S] by Robert Hood](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0579/a-history-of-the-zombie-film-to-the-mid-1990s-by-robert-hood-6120579.webp)

A History of the Zombie Film [To the Mid 1990S] by Robert Hood

Nights of the Celluloid Dead: A History of the Zombie Film [to the mid 1990s] by Robert Hood Part One: The First Steps of the Walking Dead 1. There’s Life in the Old Corpse Yet Cinematic animated corpses have been a source of fascination ever since the earliest days of film. Though less prolific in literature than their undead cousin, the vampire, zombies and other walking (and frequently murderous) dead have provided some of the most potent visual imagery in horror film history. Continually resurrected, re-imagined and re-invented through the decades, zombies still maintain a respectable presence, as witness the multitude of mainstream living dead films released since 1990, many of them sequels. These include: Braindead; Return of the Living Dead 3; Army of Darkness: Evil Dead 3; Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday; Maniac Cop 3: Badge of Silence; Pet Semetary Two; The Crow and its sequels; the lyrical Dellamorte Dellamore; The Dead Hate the Living; Route 666; Resident Evil; and the zombie comedies Weekend at Bernie’s 2; Ed and His Dead Mother; and Death Becomes Her. Though the late 1990s ushered in a diminishing of zombie content in mainstream cinema (replaced, interestingly enough, by ghosts, especially post-The Sixth Sense), independent filmmakers have remained faithful right through to the new millennium. Their films have included Shatter Dead, Vengeance of the Dead, Todd Sheet's Zombie Rampage and Zombie Bloodbath sequences, Zombie Cop, Zombie Cult Massacre, The Necro-Files, Biker Zombies and lots more besides. There has also been a horde of living dead coming from Hong Kong and Japan, with films such as The Magic Cop, Bio-Zombie, Versus, Junk and Wild Zero to the fore. -

A Strange Body of Work: the Cinematic Zombie Emma Dyson Ph

A Strange Body of Work: The Cinematic Zombie Emma Dyson Ph.D. 2009 Total number of pages: 325 1 Declaration While registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in the thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Signed……………….. Date…………. 2 Abstract A Strange Body of Work: The Cinematic Zombie This thesis investigates the changing cinematic representations of a particular figure in horror culture: the Zombie. Current critical perspectives on the figure of the Zombie have yet to establish literary and cultural antecedents to the cinematic portrayal of the Zombie, preferring to position it as a mere product of American horror films of the 1930s. This study critiques this standpoint, arguing that global uses of the Zombie in differing media indicate a symbolic figure attuned to changing cultural contexts. The thesis therefore combines cultural and historical analysis with close textual readings of visual and written sources, paying close attention to the changing contexts of global film production and distribution. In order to present the cinematic Zombie as a product of historical, geographical and cultural shifts in horror film production, the thesis begins by critiquing existing accounts of Zombie film, drawing attention to the notion of generic canons of film as determined by both popular and academic film critics and draws attention to the fractured nature of genre as a method of positioning and critiquing film texts. In this, an interdisciplinary approach, drawing on the methods of cultural-historical and psycho-analytical critiques of horror film, is appraised and then applied to the texts under discussion. -

Proquest Dissertations

Sociology of the Living Dead by Andrea Subissati, B.A. Hon. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology and Anthropology Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario July 29th 2008 © 2008, Andrea Subissati Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47644-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47644-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Copyrighted Material

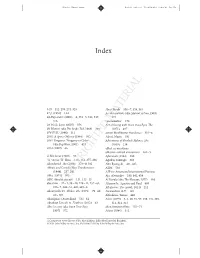

Trim Size: 170mm x 244mm Benshoff bindex.tex V3 - 06/30/2014 12:40 A.M. Page 554 Index 3-D 112, 270, 274, 325 Abu Ghraib 356–7, 359, 361 8 1∕2 (1963) 114 Acción mutante (aka Mutant Action, 1993) 28 Days Later (2002) 6, 334–5, 342, 347, 373 376 ‘‘acousmêtre” 178 28 Weeks Later (2007) 376 Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes, The 99 Women (aka Der heieTod, 1969) 368 (1971) 497 976-EVIL (1988) 311 actionblockbusterfranchises 332–6 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 502 Adorf, Mario 393 2001 Yonggary: Yonggary vs Cyker Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The (aka Reptilian, 2001) 433 (1939) 239 2012 (2009) 66 affect see emotions affective-textual encounters 104–5 ÀMaSoeur(2001) 94 Aftermath (1994) 380 ‘‘A” versus “B” films 110–112, 275, 406 Aguilar, Santiago 385 Abandoned, The (2006) 378–9, 381 Ahn Byung-ki 431, 435 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein AIDS 536 (1948) 237, 241 AIP see American International Pictures Abby (1974) 302 Aja, Alexandre 330, 342, 439 ABC (theatre circuit) 111, 113–15 Al Rissala (aka The Message, 1977) 466 abjection 32–3,COPYRIGHTED 39–40, 229–44, 257–61, Alarcon MATERIAL Jr., Agustin and Raul 480 265–7, 345–61, 420, 493–8 Albigenses, The (novel, 1824) 211 Abominable Dr. Phibes, The (1971) 79–80, Alexandrov, G.V. 182 285, 303 Alfredson, Tomas 480 Aborigines (Australian) 521–34 Alien (1979) 5, 6, 29, 91, 97, 159, 176, 292, Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies (2012) 63 312, 314, 321 Abre los ojos (aka Open Your Eyes, alien invasion films 255–71 1997) 372 Aliens (1986) 312 A Companion to the Horror Film, First Edition. -

Chapter 2 Italy

PERVERSE TITILLATION: A HISTORY OF EUROPEAN EXPLOITATION FILMS 1960–1980 By DANIEL G. SHIPKA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2007 © 2007 Daniel G. Shipka 2 To all of those who have received grief for their entertainment choices and who see the study of weird and wacky films as important to the understanding of our popular culture 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’d like to thank my committee, Dr. Jennifer Robinson, Dr. Lisa Duke-Cornell and Dr. Mark Reid for having both the courage and stomach to tackle the subject matter in many of these films. Their insistence that I dig deep within myself made this work a better one. To my chair, Dr. Bernell Tripp for her support and laughter, I am indebted. I’d also like to thank the University of Florida and the College of Journalism and Mass Communication for giving me the opportunity to complete my goals and develop new ones. I am very fortunate to have had two wonderful parents that have supported me throughout this process as well as my life. This work would not have been possible had both my mother and father not allowed me to watch all those cheesy horror movies when I was younger! I’d also like to thank my friend Debbie Jones who has stood by my side for 25 years watching and loving these movies too. The doctoral process can be a difficult one; I would like my partner in crime, Dr. -

Spanish Zombie Films: the Cases of Amando De Ossorio and Jorge Grau

Coolabah, No.18, 2016, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians / Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Spanish Zombie Films: The Cases of Amando de Ossorio and Jorge Grau Alex del Olmo Ramón ESUP-Universitat Pompeu Fabra [email protected] Copyright©2016 Alex del Olmo Ramón. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: Situated by many scholars in the lowest position of cinema monsters, the zombie has over recent years been erected into one of the main benchmarks of the current fantasy genre. From its roots located in the lush jungles of Haiti until its arrival in the West, the figure of the zombie as embodied by the living dead has a unique place in 20th-century popular culture, especially at the beginning of the 21st century. This article discusses the unique phenomenon of Spanish fantastique cinema during Franco’s dictatorship. Its historical overview explains the causes that have lead to the emergence of the Spanish fantastique film genre, taking as example the film production of two of its most emblematic Spanish film directors working in the zombie subgenre: Amando de Ossorio and Jorge Grau. This article investigates the complex relationship between fantastique films and history, based on the study of the zombie films of these two directors throughout a troubled period, with its accompanying interpretation of the evolution of the subgenre and its impact on society. Keywords: Spanish zombie films, Amando de Ossorio, Jorge Grau, fantastique. -

The Development of the Zombie Film Narrative

Zombies in a Time of Terror The Development of the Zombie Film Narrative Jasper Wezenberg 5947634 [email protected] Ferdinand Bolstraat 27-3 1072LB Amsterdam 06-20924216 Thesis guide: dr. C.J. Forceville Second reader: Amir Vudka 2 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank dr. Charles Forceville for being an excellent thesis guide who always provide me with pragmatic tips, interesting insights and fast comments. Thanks to Amir Vudka for being my second reader. I would like to thank Absaline Hehakaya and Maarten Stolz for reading parts of my unfinished thesis and providing comments. Many thank to Saskia Mollen for designing the awesome front cover. Thank to my colleagues Joost Mellink and Renée Janssen for covering for me. Thanks to my friends Niels de Groot and Rufus Baas for encouraging me. Thanks to Marek Stolarczyk, Roeland Hofman, and Marije Ligthart for being funny and supportive. Thanks to Nika Pantovic for making nice music and providing inspiration. And finally thanks to my parents and brother for being awesome people. 3 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 5 1. Generic difficulties 6 2. On zombie studies 12 3. The Quantitative of the dead 16 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 Corpus and zombie movie production numbers 21 3.3 Results 23 3.3.1 Zombie invasion narrative 23 3.3.2 Shots of deserted streets 24 3.3.3 Use of news- or found footage 25 3.3.4 Speed of zombie movement 25 3.3.5 Are they dead? 27 3.3.6 Extra: funny zombies 28 4. Zombies in a time of terror: invoking images 29 4.1 REC 29 4.2 Train to Busan 34 4.3 Land of the Dead 40 Conclusion 45 Bibliography 48 Filmography 50 Appendix A 51 Appendix B 53 4 Introduction Of all the monstrous creatures that have populated the horror stories of Western culture, the zombie may well be the most characteristic for the late 20th and early 21th century.