Lessons from Three BC Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Recreation Map

RECREATION MAP TumblerRidge.ca ■ ■ ● TRAIL DESCRIPTIONS ● EASY ■ MODERATE ◆ CHALLENGING 26. Nesbitt’s Knee Falls 35. Boulder Gardens 44. Long Lake Features: waterfall viewpoints Features: unique rock gardens, scenery, caves, tarn, Features: interesting lake, swimming Trailhead: 39 km south of Tumbler Ridge viewpoints, rock climbing Trailhead: 78 km E of Tumbler Ridge 1. Flatbed Pools ■ 9. Quality Falls ● Caution: alpine conditions, route finding skills needed, Distance / Time: 2 km return / 1-2 hrs Trailhead: 35 km S of Tumbler Ridge Distance / Time: 1 km return / 0.5 hrs Features: three pools, dinosaur prints Features: picturesque waterfall industrial traffic on access road Difficulty: moderate Distance / Time: 4 km / 3 hrs Difficulty: easy Trailhead: 1 km SE of Tumbler Ridge Caution: unbarricaded drop-offs Difficulty: moderate, strenuous in places Caution: watch for industrial traffic on access road Trailhead: 9 km NE of Tumbler Ridge 18. Mt Spieker ■ Distance / Time: 4 km return / 2 hrs Caution: some scree sections, rough route in places, Distance / Time: 2.5 km return / 1-2 hrs Features: alpine summit massif 27. Greg Duke Trails ● 45. Wapiti Lake – Onion Lake ◆ Difficulty: moderate avoid falling into deep rock crevices Difficulty: easy Trailhead: 39 km W of Tumbler Ridge Features: forest and lakes, fishing, swimming Features: long trail to remote mountain lakes, cabin on Caution: avoid swimming, river crossings at high water Caution: slippery below falls, beware of flash floods Distance / Time: variable, 4-10 km / 2-5 hrs Trailhead: 55 km S of Tumbler Ridge 36. Shipyard–Titanic, Tarn & Towers Trails ■ ● Wapiti Lake and diving into pools, trail initially follows “Razorback” 10. -

Bch 2005 04.Pdf

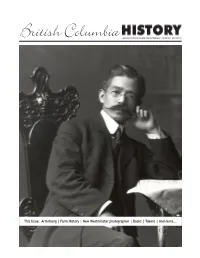

British Columbia Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.38 No.4 2005 | $5.00 This Issue: Armstrong | Farm History | New Westminster photographer | Books | Tokens | And more... British Columbia History British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 !online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, and news items dealing with any aspect of the Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. The Honourable Iona Campagnolo. PC, CM, OBC Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Editor, British Columbia History, Honourary President Melva Dwyer John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 e-mail: [email protected] Officers Book reviews for British Columbia History,, AnneYandle, President 3450 West 20th Avenue, Jacqueline Gresko Vancouver BC V6S 1E4, 5931 Sandpiper Court, Richmond, BC, V7E 3P8 !!!! 604.733.6484 Phone 604.274.4383 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] First Vice President Patricia Roy Subscription & subscription information: 602-139 Clarence St., Victoria, B.C., V8V 2J1 Alice Marwood [email protected] #311 - 45520 Knight Road Chilliwack, B. C.!!!V2R 3Z2 Second Vice President phone 604-824-1570 Bob Mukai email: [email protected] 4100 Lancelot Dr., Richmond, BC!! V7C 4S3 Phone! 604-274-6449!!! [email protected]! Subscriptions: $18.00 per year Secretary For addresses outside Canada add $10.00 Ron Hyde #20 12880 Railway Ave., Richmond, BC, V7E 6G2!!!!! Phone: 604.277.2627 Fax 604.277.2657 [email protected] Single copies of recent issues are for sale at: Recording Secretary Gordon Miller - Arrow Lakes Historical Society, Nakusp BC 1126 Morrell Circle, Nanaimo, BC, V9R 6K6 [email protected] - Book Warehouse, Granville St. -

STONY LAKE History, Trails & Recreation

STONY LAKE History, Trails & Recreation Stony Lake watercolour, by Euphemia McNaught, 1976 (view from the Stony Lake Ranger Station) The well preserved remains of the old bridge at Stony Lake Stony Lake today Stony Lake, popular for camping, fishing and hiking, lies southeast of Tumbler Ridge, fifty-five kilometers by road via the Boundary Road (Heritage Highway East). Its shores and surrounding area have been the scene of some of the most intriguing history in northeastern British Columbia, such as its first tourist resort and the discovery of natural gas in Canada. 2 Access to Stony Lake today is via a slightly rough road that leads for 1.6 kilometres from the Boundary Road (55 kilometres from Tumbler Ridge) to the Forest Recreation Site on the northeastern shore of the lake. Here there are a number of campsites and fire pits, and a simple boat launch area. Within this area would have stood trapper Emil Kruger’s old 1930s cabin, of which there is no trace. (Its location was under 100 metres east of the boat launch and in the tiny bay just east of the prominent knoll, so as to avoid the force of the prevailing westerly winds.) The lake remains popular for fishing, predominantly Northern Pike, although the prodigious catches of the late 1930s no longer occur. The long reach can make for large waves. Canoeing in an easterly direction along a narrower portion of the lake to the terminal beaver dam is more sheltered, with opportunities for wildlife and bird watching. There are tantalizing remains of the Monkman days, which make for a fascinating trip back into the past. -

What Makes Us Canadian? History Detectives Explore Alberta’S Archives - the Case of the Unfinished Phrases - Albert, Your Trusty Assistant, Is in a Pickle

Name: What Makes Us Canadian? History Detectives Explore Alberta’s Archives - The Case of the Unfinished Phrases - Albert, your trusty assistant, is in a pickle. He needs your help to solve a mystery. He has to put together some phrases that have been jumbled. He’s got the first parts but he needs you to find the right endings. Albert is counting on you to figure them out. To solve this case, you must find the phrases in the ‘What Makes Us Canadian’ archives and write the correct endings from the Answers list. (Look for the Clue below.) 1. log 2. Monkman 3. Canyon 4. Pathfinder 5. raise 6. Peace River 7. vounteer 8. Alex 9. work 10. tools in Answers: labour Pass crew hand Outlet funds bridge Monkman Creek Car Clue: SPRA Super Sleuth What does ‘volunteer work crew’ mean? Why do you think the work crews were volunteer? Read the pages on the Monkman Pass Trail to find out. Do a short report on what you found out about the Monkman Pass Highway. Your report can be a written one or you can create and present it as a slide show on a computer. SPR-1 ©Archives Society of Alberta What Makes Us Canadian? Answer Key and Teacher Resources - The Case of the Unfinished Phrases - Answers: 1. log bridge 2. Monkman Pass 3. Canyon Creek 4. Pathfinder Car 5. raise funds 6. Peace River Outlet 7. Volunteer labour 8. Alex Monkman 9. work crew 10. tools in hand Archive(s) Used: South Peace Regional Archives pp.147-156 Teaching Strategies: 1. -

“The Re-Birth of a Nation” the Kelly Lake Cree Peoples the REBIRTH

“The Re-Birth of a Nation” the Kelly Lake Cree Peoples THE REBIRTH OF A NATION THE KELLY LAKE CREE PEOPLES Marian Kwarakwante 1 “The Re-Birth of a Nation” the Kelly Lake Cree Peoples Throughout this background paper, I will use the Cree people as an example because that is the culture that I am a part of and I was fortunate to be raised with the traditional teachings of the Cree. Therefore my combined knowledge base comes both from the oral history of the elders who raised me as well as from my education. I do not however, purport to speak on behalf of the Kelly Lake Cree Nation or the Rocky Mountain Cree Tribe. Introduction In most First Nation communities, anonymity is the basis for preserving traditional knowledge of the land. For most part, historic records refer to First Nations people in the most marginal terms and many of the artefacts in Provincial museums today are inconsequentially referred and labelled such as “Plains Cree arrow” but does not identify to whom it may have belonged or particular tribes to which it may have come from. The purpose of this background paper is not only to outline on the surface history of Kelly Lake Cree peoples but also to find out who these people were. A genealogy was developed not only for the Kelly Lake Cree Nation land claim but also for the close relations and more distant association with aboriginal families could be studied. The requisites in providing a basis of terms under Section 35 of the Constitution Act the term First Nation and Indian references to what is defined as “Aboriginal”. -

Wilderness Hiking in Monkman Provincial Park

Monkman Provincial Park TUMBLER RIDGE Kinuseo Falls Inset Legend Kinuseo Downstream Falls 1000 Ho Information Hiking Trail Viewpoint ok C See Kinuseo ree Falls Inset k Parking Unmaintained Wilderness Route Leake Toilets Viewpoint Viewpoint Riverside Camping Viewpoint Creek Backcountry or Park Boundary Murray River Chambers Wilderness Camping Viewpoint Imperial Ridge Viewing Monkman Falls Inset Platform Upper Viewpoint Murray River Lower Moore Falls Day Use Area Camp (km 7) Upper Moore Falls 1000 1500 P I ONEER 2000 Brooks Falls RANGE 1000 Castle Mtn Shire Falls Cascades Camp 1000 Murr a y Monkman Falls Monkman Lake Trail Mt Cornock Boone Taylor 1500 McGinnis Falls Peak Monkman Lake Trail Chambers Falls The Devil’s Creek Shark’s Fin eek r Camp 1000 Trot Camp C (km15) Devil’s Creek See Monkman Bulley C 2000 Holmes Falls Inset 1000 N Lake Cascades Camp (km20) 2000 W E Mt Gauthier Devil’s Creek 0 0.5 1 Camp (km 22) D 2000 R e i S Mt Jim Young v v Scale in kilometres Monkman i 1500 e l s r 1500 Lake C r 2000 r eek R 1500 e 1500 Note: Trail turns into e k Mt Watts 1500unmaintained 2000 Monkman Lake1500 Route at this point. 1500 Camp (km 25) See warning below d n B u l a l e y 2000 1500 m 1500 k Monkman Pass Mt Vreeland n 2000 1500 o 1500 Memorial2000 Trail Lupin 1500 Monkman M Hiking Route Lake C Glacier r WILDERNESS2000 CAMPING Lower e e k HughGPS Lake Position Blue 1500 2000 MONKMAN 1500 Camp (km 33) N54º 32.639’ W121º 10.229’ Lake 2000 Parsnip PASS Hugh 10 U 618348E 6045588N 1500 Lake Paxton Peak Glacier 2000 F Paxton 2000 o 2000 Mt Barton -

Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC)

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-161 ISSUE 17, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) BR 751-401-161 Copyright Page Issue 17, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-161 Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) Issue 17, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) BR 751-401-161 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 17, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-161 Geographical Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) Issue 17, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Canada - British Columbia (BC) Table of Contents 1. -

Monkman Pass Hiking Route Memorial Trail

MONKMAN PASS MEMORIAL TRAIL HIKING ROUTE –1– The Monkman Pass Memorial Trail is dedicated to the pioneers that dared to follow a dream and take control over their own destiny . These people did not just live in the Peace Country , they created it . The Monkman Pass Memorial Trail Hiking Route is a new, unforget- table, class hiking destination that includes major waterfalls and rivers, lakes, temperate boreal forest, alpine meadows and optional alpine summits. The six day wilderness trail leads through magnificent, remote, untouched mountain terrain, suffused with inspiring, tangible history. The Monkman Pass Memorial Trail comprises a Driving Tour from Grande Prairie to Kinuseo Falls via Tumbler Ridge, and the Hiking Trail from Kinuseo Falls over the Rocky Mountains to Hobi’s Cabin on the Herrick River. The hiking trail is sixty-three kilometres long, and takes five to six days to complete. There are many possible side trips for the adventurous hiker that can make for an expedition of seven to ten days. For those seeking shorter trips, the return hike from Kinuseo Falls to the Cascades and Monkman Lake requires just three days. The trail lies mostly within Monkman Provincial Park and for the most part follows the old Monkman route over the Rockies. Once at Hobi’s Cabin on the Herrick River, it is necessary either to travel by river boat to Prince George, or to be ferried across the Herrick to a waiting ve- hicle. Alternatively, some hikers may wish to hike the trail from south to north and to be dropped off by boat at Hobi’s Cabin. -

South Peace Regional Archives Library Catalogue Page 1

South Peace Regional Archives Library Catalogue Place of Type Title Scope Date Author Editor Publisher Publishing Chamber of Nine brochures produced in the 1960s advertising businesses, services, recreation Commerce and 1960s Brochures 1960-1968 Grande Prairie opportunities City of Grande Collections Prairie 57 Ways to use Heinz Condensed H.J. Heintz Co. of Leamington 57 Ways to use Heinz Condensed Soups 1953 Collections Soups Canada Ont. Northern Alberta A handbook produced by th Northern Alberta Development Council for northerners who are A Board Member's Handbook 1975-1985 Development directors on community boards. Collections Council A Catechism with the Order of Cambridge The Catechism learned by children in the Anglican Church to prepare them for confirmation. [1940] Church of England Toronto Confirmation University Press Collections Canadian Army Training Pamphlet No. 1, with information on Infantry Drill, Marching and J.O. Patenaude, A General Instructional Department of Physical Training; Weapon Training; Application of Fire; Protection Against Gas; Organization 1940 I.S.O., King's Ottawa, ON Background for the Young Soldier National Defence and Tactical Training; Field Engineering; and Military Law and Interior Economy. Printer Collections Information for the new Canadians including custom duties, government services, homestead Minister of Government of A Manual of Citizenship lands, immigration halls, assistance to women, emigration agents, banks, education, health 1926 Immigration and Ottawa Canada services, etc. Colonization Collections A New Horned Dinosaur from an Philip Currie, Wann A close look at the anatomy, relationships, growth and variation, behavior, ecology and other National Research Upper Cretaceous Bone Bed in 2008 Langston, Darren biological aspects of this dinosaur species. -

Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects

BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 75 LAKP-British Columbia 75 Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects Introduction 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT WATSON LAKE 600 FT 300 FT DEASE LAKE 0 SEA LEVEL FORT NELSON WARE INGENIKA MASSET PRINCE RUPERT TERRACE SANDSPIT SMITHERS FORT ST JOHN MACKENZIE BELLA BELLA PRINCE GEORGE PORT HARDY PUNTZI MOUNTAIN WILLAMS LAKE VALEMOUNT CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX TOFINO KAMLOOPS GOLDEN LYTTON NANAIMO VERNON KELOWNA FAIRMONT VICTORIA PENTICTON CASTLEGAR CRANBROOK Map 4-1 - Topography of GFACN31 Domain This chapter is devoted to local weather hazards and effects observed in the GFACN31 area of responsibility. After extensive discussions with weather forecasters, FSS personnel, pilots and dispatchers, the most common and verifiable hazards are listed. BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 76 76 CHAPTER FOUR Most weather hazards are described in symbols on the many maps along with a brief textual description located beneath it. In other cases, the weather phenomena are better described in words. Table 3 (page 74 and 207) provides a legend for the various symbols used throughout the local weather sections. South Coast 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT PORT HARDY 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT 600 FT 300 FT 0 SEA LEVEL CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX PEMBERTON TOFINO VANCOUVER HOPE NANAIMO ABBOTSFORD VICTORIA Map 4-2 - South Coast For most of the year, the winds over the South Coast of BC are predominately from the southwest to west. During the summer, however, the Pacific High builds north- ward over the offshore waters altering the winds to more of a north to northwest flow. -

Visitor Experience Guides

VISITOR EXPERIENCE GUIDE TumblerRidge.ca TUMBLER Direct operator for the Summer RIDGE OFFICIAL GUIDE Riverboat Tours Jeep Tours ORV Tours & Rentals Camping Gear Rentals Welcome! umbler Ridge is a dream destination for outdoor enthusiasts, from high-energy to laid back. With accessible year-round recreation opportunities for all ages, interests and abilities, the possibilities are as diverse as the landscapes in which Tthey appear. Nearly 1600 km2 (600+ mi2) of Provincial Parks and wilderness areas enshrine Choose to Experience an a huge variety of landscapes, vegetation and wildlife – gifts of nature that allow you to discover the heart and soul of a region that will always be wild. Forty-eight designated trails for hiking lead to special places – caves, Adventure You Will fascinating geological formations, waterfalls and dinosaur trackways. Always Remember! CONTENTS 36 Quick Facts about Tumbler Ridge 4 Tumbler Ridge UNESCO Global Geopark 6 Discover Dinosaurs – Facts and Tours 10 Waterfalls 14 Recreation Map & Trail Descriptions Pullout Winter Trails 18 Endless Riding – ATVing 22 Snowmobile & Snowshoe Tours Fishing 24 Snowmobile & Snowshoe Rentals Golf 25 Avalanche Gear Rentals Winter Adventure 26 Winter Gear Rentals Ice Fishing Rentals Bike & Board 32 Community Centre 34 What’s Happening 36 Northern British History 38 Columbia Camping and Touring the North 40 Visitor Services 43 Wildlife & Safety 44 12 Tumbler Ridge How To Get Here Map 46 UNESCO Global Geopark www.wildrivertours.ca All rights reserved. © 2018 District of Tumbler Ridge