Leblond Alyssa 2020 Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![“They Demanded — Under Duress — That We Stop Supporting Belinda [Karahalios]. We Are Appalled at This Bullying An](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9360/they-demanded-under-duress-that-we-stop-supporting-belinda-karahalios-we-are-appalled-at-this-bullying-an-89360.webp)

“They Demanded — Under Duress — That We Stop Supporting Belinda [Karahalios]. We Are Appalled at This Bullying An

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report August 20, 2020 Quotation of the day “They demanded — under duress — that we stop supporting Belinda [Karahalios]. We are appalled at this bullying and abuse of power. It is a direct attack on our democracy!” The now-derecognized PC riding association in Cambridge sends out flyers attacking Premier Doug Ford and the PC Party over alleged "intimidation tactics." Today at Queen’s Park Written by Sabrina Nanji On the schedule The house reconvenes on Monday, September 14. The roster for the Select Committee on Emergency Management Oversight — which will scrutinize ongoing extensions of emergency orders via Bill 195 — has been named. The majority-enjoying PC side will feature Bob Bailey, Christine Hogarth, Daryl Kramp, Robin Martin, Sam Oosterhoff, Lindsey Park and Effie Triantafilopoulos. The New Democrat members are Gilles Bisson, Sara Singh and Tom Rakocevic; Liberal MPP John Fraser will take up the Independent spot. The committee was struck as an accountability measure because the PCs empowered themselves to amend or extend the emergency orders for up to the next two years, without requiring a vote or debate in the legislature. Bill 195, the enabling law, also requires the premier or a designate of his choosing to appear at the special committee to justify any changes to the sweeping emergency orders. Premier watch An RFP for the next leg of the Eglinton Crosstown tunnelling project will be issued today. Premier Doug Ford announced the move in Mississauga Tuesday alongside cabinet’s transportation overseers Caroline Mulroney and Kinga Surma. Three construction consortiums have already been shortlisted and are now able to present their detailed costing plans to Infrastructure Ontario. -

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Monique Hughes Ajax [email protected] Michael Mantha Algoma-Manitoulin [email protected] Pekka Reinio Barrie-Innisfil [email protected] Dan Janssen Barrie-Springwater-Ono- [email protected] Medonte Joanne Belanger Bay of Quinte [email protected] Rima Berns-McGown Beaches-East York [email protected] Sara Singh Brampton Centre [email protected] Gurratan Singh Brampton East [email protected] Jagroop Singh Brampton West [email protected] Alex Felsky Brantford-Brant [email protected] Karen Gventer Bruce-Grey-Owen Sound [email protected] Andrew Drummond Burlington [email protected] Marjorie Knight Cambridge [email protected] Jordan McGrail Chatham-Kent-Leamington [email protected] Marit Stiles Davenport [email protected] Khalid Ahmed Don Valley East [email protected] Akil Sadikali Don Valley North [email protected] Joel Usher Durham [email protected] Robyn Vilde Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Amanda Stratton Elgin-Middlesex-London [email protected] NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Taras Natyshak Essex [email protected] Mahamud Amin Etobicoke North [email protected] Phil Trotter Etobicoke-Lakeshore [email protected] Agnieszka Mylnarz Guelph [email protected] Zac Miller Haliburton-Kawartha lakes- [email protected] -

GLP Weekly-January 24, 2020

January 24, PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 14, 2020 GLP WEEKLY Issue 3 TWO PEO CHAPTERS PARTICIPATE IN NEW YEAR’S LEVEE WITH YORK CENTRE MPP PEO West Toronto Chapter GLP Chair Janet Han, P.Eng. (centre) spoke with Roman Baber, MPP (York Centre) (right) and Ontario College of Teachers Councillor, Bob Cooper (left) at a New Year’s Levee hosted by MPP Baber on January 19. For more on this story, see page 7. Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at https://www.peo.on.ca/index.php/about-peo/glp-weekly- newsletter *Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue of the GLP Weekly will be published on January 31, 2020. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO GRAND RIVER CHAPTER ATTENDS CHINESE NEW YEAR EVENT WITH TWO MPPS 2. ENGINEERS SPEAK WITH MPP AT LEVEE IN WATERLOO 3. PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON COMMITTEE RE-ELECTS COUNCILLORS AS CHAIR & VICE- CHAIR 4. ENGINEERING DIMENSIONS PUBLISHES STORY ABOUT MP ENGINEERS 5. PEO COUNCIL ELECTION VOTING OPEN UNTIL FEB 21 EVENTS WITH MPPs PEO GOVERNMENT LIASON PROGRAM (GLP) The PEO Government Liaison Program’s main objective is to ensure that government, PEO members, and the public continue to recognize PEOs regulatory mandate, in particular its contributions to maintaining the highest level of professionalism among engineers working in the public interest. -

PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 30 PEO OAKVILLE CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP COMMUNITY EVENT

September 27, PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 30 PEO OAKVILLE CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP COMMUNITY EVENT PEO Oakville Chapter GLP Co-coordinator Jeffrey Lee, P.Eng. (left), and Chapter Treasurer, Edward Gerges, P.Eng. (second to left), attended a community event on September 14 hosted by Effie Triantafilopoulos, MPP (Oakville–North Burlington), Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Long-Term Care (centre). Also in the photo is Peter Bethlenfalvy, MPP (Pickering— Uxbridge), President of the Treasury Board (second to right). For more on this story, see page 6. The GLP Weekly is published by the Professional Engineers of Ontario (PEO). Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at www.glp.peo.on.ca. To sign up to receive PEO’s GLP Weekly newsletter please email: [email protected]. *Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published October 4. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO WINDSOR-ESSEX CHAPTER GLP CHAIR SPEAKS WITH NDP MPP AT A COMMUNITY EVENT 2. PEO EAST TORONTO CHAPTER ATTENDS PROJECT SPACES EVENT WITH NDP MPP 3. ENGINEERS PRESENTED WITH ONTARIO VOLUNTEER SERVICE AWARDS BY MPPS 4. NEW ONTARIO LEGISLATURE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME INTERNS SELECTED FOR 2019/2020 5. PC AND NDP MPPs TO SPEAK AT PEO GLP ACADEMY AND CONGRESS ON OCTOBER 5 EVENTS WITH MPPs PEO WINDSOR-ESSEX CHAPTER GLP CHAIR SPEAKS WITH NDP MPP AT A COMMUNITY EVENT (WINDSOR) - PEO Windsor-Essex Chapter GLP Chair Asif Khan, P.Eng., had a chance to speak with NDP Community and Social Services Critic Lisa Gretzky, MPP (Windsor West), at a community event in Windsor on September 8. -

November 24, 2020 MPP Daryl Kramp, 8 Dundas St. W Napanee, ON

www.odph.ca [email protected] @RDsPubHealthON November 24, 2020 MPP Daryl Kramp, 8 Dundas St. W Napanee, ON K7R 1Z4 [email protected] Dianne Dowling, Chair Food Policy Council for KFL&A [email protected], [email protected] Dear MPP Kramp and Ms. Dowling: Re: Support for Bill 216 – Food Literacy for Students Act, 2020 Ontario Dietitians in Public Health (ODPH), the independent and official voice of Registered Dietitians working in Ontario’s public health system offers our support for Bill 216 – Food Literacy for Students Act, 2020. ODPH’s mission is to advance public health nutrition through member and partner collaboration in order to improve population health and health equity locally and provincially. Food literacy is an important life skill encompassing much more than food and cooking skills1 and is essential for a solid foundation of healthy eating behaviours. We are pleased that Bill 216 will require school boards to offer experiential food literacy education to all Ontario students in grades 1 through 12. This requirement in the Ontario curriculum will ensure that all children and youth develop vital skills to inform food choices throughout their lives. We know that using hands-on, experiential learning about food contributes significantly to increasing vegetable and fruit consumption for students aged 4-18 years2. As well, youth (18-23 years) who have self-perceived cooking skills are more likely to have positive nutrition-related outcomes 10 years later (i.e., more frequent preparation of meals including vegetables, and less frequent consumption of fast food)3. The benefits of food literacy and cooking programs extends beyond healthy eating behaviours. -

2018 Ontario Candidates List May 8.Xlsx

Riding Ajax Joe Dickson ‐ @MPPJoeDickson Rod Phillips ‐ @RodPhillips01 Algoma ‐ Manitoulin Jib Turner ‐ @JibTurnerPC Michael Mantha ‐ @ M_Mantha Aurora ‐ Oak Ridges ‐ Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian ‐ @yaqubian Michael Parsa ‐ @MichaelParsa Barrie‐Innisfil Ann Hoggarth ‐ @AnnHoggarthMPP Andrea Khanjin ‐ @Andrea_Khanjin Pekka Reinio ‐ @BI_NDP Barrie ‐ Springwater ‐ Oro‐Medonte Jeff Kerk ‐ @jeffkerk Doug Downey ‐ @douglasdowney Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff ‐ @RQuaiff Todd Smith ‐ @ToddSmithPC Joanne Belanger ‐ No social media. Beaches ‐ East York Arthur Potts ‐ @apottsBEY Sarah Mallo ‐ @sarah_mallo Rima Berns‐McGown ‐ @beyrima Brampton Centre Harjit Jaswal ‐ @harjitjaswal Sara Singh ‐ @SaraSinghNDP Brampton East Parminder Singh ‐ @parmindersingh Simmer Sandhu ‐ @simmer_sandhu Gurratan Singh ‐ @GurratanSingh Brampton North Harinder Malhi ‐ @Harindermalhi Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi ‐ @SukhwantThethi Prabmeet Sarkaria ‐ @PrabSarkaria Brampton West Vic Dhillon ‐ @VoteVicDhillon Amarjot Singh Sandhu ‐ @sandhuamarjot1 Brantford ‐ Brant Ruby Toor ‐ @RubyToor Will Bouma ‐ @WillBoumaBrant Alex Felsky ‐ @alexfelsky Bruce ‐ Grey ‐ Owen Sound Francesca Dobbyn ‐ @Francesca__ah_ Bill Walker ‐ @billwalkermpp Karen Gventer ‐ @KarenGventerNDP Burlington Eleanor McMahon ‐@EMcMahonBurl Jane McKenna ‐ @janemckennapc Cambridge Kathryn McGarry ‐ Kathryn_McGarry Belinda Karahalios ‐ @MrsBelindaK Marjorie Knight ‐ @KnightmjaKnight Carleton Theresa Qadri ‐ @TheresaQadri Goldie Ghamari ‐ @gghamari Chatham‐Kent ‐ Leamington Rick Nicholls ‐ @RickNichollsCKL Jordan -

Sustainontario.Com Mr. Daryl Kramp

Mr. Daryl Kramp - Member for Hastings - Lennox and Addington Room 269, Legislative Building Queen’s Park Toronto, ON M7A 1A8 January 13, 2021 Re: Bill 216 – Food Literacy for Students Act Dear Mr. Kramp, On behalf of Sustain Ontario and Sustain’s Ontario Edible Education Network I’m writing to express our enthusiastic support for Bill 216, the Food Literacy for Students Act. We would like to start by expressing a big thank you for introducing this important Bill into the Ontario Legislature. Sustain Ontario is a province-wide, cross-sectoral alliance that promotes healthy food and farming. Our mission is to provide coordinated support for productive, equitable and sustainable food and farming systems that support the health and wellbeing of all people in Ontario, through collaborative action. Sustain Ontario hosts the Ontario Edible Education Network, which supports individuals and organizations across the province to share resources, ideas, and experience and to better undertake food literacy efforts to get children and youth eating, growing, cooking, celebrating, and learning about healthy, local and sustainably produced food. In 2016 Sustain Ontario provided feedback to inform the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Community- Connected Experiential Learning Policy Framework. We shared how food and hands-on food literacy education can act as powerful catalysts for students to acquire the academic skills and personal skills that contribute to long-term success including critical thinking, innovation, collaboration, problem- solving, numeracy, literacy, communications, and thinking about complex issues including health, the environment, the economy, and our place in the broader food system. We also spoke about how those who provide experiential food-based learning in the province regularly confirm that hands-on experiences that let students connect with food are exciting, engage students who are less enthusiastic about school than others, and help make learning real. -

April 26, 2019

PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM April 26, Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 13 PEO BRAMPTON CHAPTER ENGINEER PARTICIPATES IN EVENT WITH NDP LEADER AND MPPs (BRAMPTON) - PEO Brampton Chapter Treasurer Ranjit Gill, P.Eng., (left) spoke with Opposition Leader Andrea Horwath, MPP (NDP—Hamilton Centre) (right) at a Sikh Heritage Month event in Brampton on April 14. Also attending were Brampton NDP MPPs, Gurratan Singh, (Brampton East), Sara Singh, (Brampton Centre) and Kevin Yarde, (Brampton North). For more on this story, see page 6. The GLP Weekly is published by the Professional Engineers of Ontario (PEO). Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 87,500 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at www.glp.peo.on.ca. To sign up to receive PEO’s GLP Weekly newsletter please email: [email protected]. *Deadline for all submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published on May 3, 2019. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. MINISTER ATTENDS PEO ALGONQUIN CHAPTER NATIONAL ENGINEERING MONTH EVENT 2. PEO ATTENDS OSPE 10TH ANNUAL LOBBY DAY AND MPP RECEPTION 3. THREE MPPs PARTICIPATE IN PEO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER NATIONAL ENGINEERING MONTH 4. PEO REPRESENTED AT EVENT WITH TWO MINISTERS AND ENGINEER MPP 5. PEO TO HOLD ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING IN TORONTO ON MAY 4 EVENTS WITH MPPs MINISTER ATTENDS PEO ALGONQUIN CHAPTER NATIONAL ENGINEERING MONTH EVENT Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry John Yakabuski, MPP (PC—Renfrew-Nipissing-Pembroke), (left), attended the PEO Algonquin Chapter National Engineering Month event on April 6. -

2018 Ontario Candidates List Updated June 1

Riding Ajax Joe Dickson - @MPPJoeDickson Rod Phillips - @RodPhillips01 Monique Hughes - @monique4ajax Algoma - Manitoulin Charles Fox - @votecharlesfox Jib Turner - @JibTurnerPC Michael Mantha - @M_Mantha Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian - @yaqubian Michael Parsa - @MichaelParsa Katrina Sale - No social media Barrie-Innisfil Ann Hoggarth - @AnnHoggarthMPP Andrea Khanjin - @Andrea_Khanjin Pekka Reinio - @BI_NDP Barrie - Springwater - Oro-Medonte Jeff Kerk - @jeffkerk Doug Downey - @douglasdowney Dan Janssen - @bsom_ondp Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff - @RQuaiff Todd Smith - @ToddSmithPC Joanne Belanger - No social media Beaches - East York Arthur Potts - @apottsBEY Sarah Mallo - @sarah_mallo Rima Berns-McGown - @beyrima Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain - No social media Harjit Jaswal - @harjitjaswal Sara Singh - @SaraSinghNDP Brampton East Parminder Singh - @parmindersingh Simmer Sandhu - @simmer_sandhu Gurratan Singh - @GurratanSingh Brampton North Harinder Malhi - @Harindermalhi Ripudaman Dhillon - @ripudhillon_bn Kevin Yarde - @KevinYardeNDP Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi - @SukhwantThethi Prabmeet Sarkaria - @PrabSarkaria Paramjit Gill - @ParamjitGillNDP Brampton West Vic Dhillon - @VoteVicDhillon Amarjot Singh Sandhu - @sandhuamarjot1 Jagroop Singh - @jagroopsinghndp Brantford - Brant Ruby Toor - @RubyToor Will Bouma - @WillBoumaBrant Alex Felsky - @alexfelsky Bruce - Grey - Owen Sound Francesca Dobbyn - @Francesca__ah_ Bill Walker - @billwalkermpp Karen Gventer - @KarenGventerNDP Burlington Andrew Drummond - No Twitter, -

Friday, November 20

5/26/2021 Friday November 20 University-Rosedale Update Subscribe Past Issues Translate Click here to view this email in your browser. Friday November 20 Update Dear Neighbour, After weeks of rising COVID-19 cases and mounting public pressure, the Ford government announced lockdown measures for Toronto and Peel. I support this decision. I know it’s hard but it’s necessary to keep people alive. At the same time, it’s imperative we provide support to businesses in need, including direct rent relief, paid sick days, and a temporary ban on commercial evictions. This is the worst crisis we have experienced since World War II, but I know we can get through it. In response to the new restrictions, our office is now closed to the public. We will continue to do our best to provide help to you via phone, zoom, and email. Please reach out if you need anything. Stay safe. Jessica Bell (MPP for University-Rosedale) My newsletter for this week includes: Further COVID-19 Restrictions for Toronto and Peel Auditor General finds Ford is harming climate action, environment NDP urges government to save Kensington Update on PMB Bill 205 - Protecting Tenants Join our Housing Town Hall on Thursday November 26 https://mailchi.mp/ndp/update-from-mpp-bell-on-covid-19-coronavirus-13303182?e=%5BUNIQID%5D 1/13 5/26/2021 Friday November 20 University-Rosedale Update Transgender Day of Remembrance Subscribe Past Issues Translate Monday Motion calling for Ford to Condemn McVety Building Transit Right – Roundtable Held Government to develop cargo e-bike program PIAC Conference this weekend ABC Residents Association Hosts its 63rd AGM TDSB Trustee Chris Moise hosts Ward Forum: Staying Well During COVID-19 BENA – Political Panel Video Now On-line Rosedale Residents: let us know what is important to you! Rosedale Food Drive a Success ~ “Who’s Hungry” Report Released Further COVID-19 Restrictions The government announced this afternoon further restrictions for Toronto and Peel in an effort to reduce the rapidly increasing number of COVID-19 cases in these two areas. -

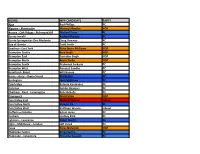

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Rod Phillips

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Rod Phillips PC Algoma—Manitoulin Michael Mantha NDP Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Michael Parsa PC Barrie-Innisfil Andrea Khanjin PC Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Doug Downey PC Bay oF Quinte Todd Smith PC Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP Brampton Centre Sara Singh NDP Brampton East Gurratan Singh NDP Brampton North Kevin Yarde NDP Brampton South Prabmeet Sarkaria PC Brampton West Amarjot Sandhu PC Brantford - Brant Will Bouma PC Bruce—Grey—Owen Sound Bill Walker PC Burlington Jane McKenna PC Cambridge Belinda Karahalios PC Carleton Goldie Ghamari PC Chatham - Kent - Leamington Rick Nicholls PC Davenport Marit Stiles NDP Don Valley East Michael Coteau Liberal Don Valley North Vincent Ke PC Don Valley West Kathleen Wynne Liberal Dufferin—Caledon Sylvia Jones PC Durham Lindsey Park PC Eglinton—Lawrence Robin Martin PC Elgin—Middlesex—London Jeff Yurek PC Essex Taras Natyshak NDP Etobicoke Centre Kinga Surma PC Etobicoke—Lakeshore Christine Hogarth PC Etobicoke North Doug Ford PC Flamborough - Glanbrook Donna Skelly PC Glengarry—Prescott—Russell Amanda Simard PC Guelph Mike Schreiner Green Haldimand—NorFolk Toby Barrett PC Haliburton—Kawartha Lakes— Brock Laurie Scott PC Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath NDP Hamilton East—Stoney Creek Paul Miller NDP Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor NDP Hamilton West - Ancaster - Dundas Sandy Shaw NDP Hastings-Lennox-Addington Daryl Kramp PC Humber River-Black Creek Tom Rakocevic NDP Huron—Bruce Lisa Thompson PC Kanata - Carleton Merrilee Fullerton PC Kenora—Rainy -

Approval of Cannabis Stores in Brampton.Pdf

February 10, 2021 Hon. Doug Ford Premier of Ontario Room 281 Legislative Building, Queen’s Park Toronto, ON M7A 1A1 Dear Premier Ford, We are writing to share concerns we have heard from community members in Brampton who are opposed to approving additional cannabis stores in the city. The Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario is currently reviewing over 30 applications for cannabis stores in the City of Brampton. The community is concerned that your government is allowing numerous private operators to set up across the city, and they are worried about the potential impact these additional stores will have on their surroundings and young children in their neighbourhoods. It is crucial that when determining the location of cannabis shops, the concerns of Ontarians are taken into consideration. That is why NDP MPPs Gurratan Singh and Kevin Yarde, alongside other community members, wrote to you to raise concerns about the government allowing shops to set up near schools – something that went against the explicit wishes of the community. It is also why NDP MPP Marit Stiles introduced Bill 235, to allow municipal authorities and the local community to have a greater say in where and how many cannabis licenses are issued. Without meaningful local input and consultation with the community, the Conservative Government's actions in allowing the approval of additional cannabis stores could have grave consequences for Brampton residents. We are calling on you to support this NDP legislation and address the situation in Brampton. Communities should be able to benefit from the legalization of Cannabis while also protecting their city’s diversity, character and the best interests of our communities.