Foreign Direct Investment and Development in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study on Kingfisher Airlines Crisis Pdf

Case study on kingfisher airlines crisis pdf Continue Case StudiesTrastigation RetailAlbal RetailersIndeceives Retail Finance Administration, Accounting - Financial Management Management - Corporate FinanceInvesting - BankingLeadershipLeadership,Organizational Changes - ExecutivesCompany planning Corporate Management - Business Ethics Corporation Corporate Social ResponsibilityMusendal Trade - Business ⁄ BusinessOperations - Project ManagementSocial NetworkKitay-related CasesIndia Related CasesWomen Executives ⁄ CEO's CasebooksCourse CaseInterviewsEffective Executive InterviewVideExecutive BriefMovie Based on Case Research Morko at IBSCDCBlogContact Code : FCF0021 Year : 2012 Industry: Aviation Industry: Aviation Industry Region Aviation Industry : India Teaching Note: Not available structured destinations :Not available OR Abstract: Kingfisher Airlines, which revised air traffic to India, suffered from financial turbulence in late 2011 due to growing debt and a shortage of expected revenue. Despite restructuring the debt with the help of creditors, airlines found it difficult to get out of their problems. The case tracks the transformation in the Indian aviation sector, as well as the ups and downs of Kingfisher Airlines. It contains information about the complex debt restructuring of Kingfisher Airlines. Case studies of best practices - Vol. I Case Research on the Aviation Industry for Business Books Click here for the case e-books Click here for the Educational Goals: Understand the Concept of Capital Structure and Capital Structure -

Lex Indis Profile

BRIEF PROFILE Lex Indis, Law Offices, a full-service law firm, having offices in New Delhi, Mumbai and Lucknow, has rich experience in providing cost effective solutions in diverse areas of legal practice. The Team at Lex Indis possesses proven expertise in the fields of litigation and non-litigation practices. We have proficiency in advisory and documentation work including audit and compliance management. With an eye on Integrity, Innovation, Involvement and Impact, our strength lies in a vastly experienced and knowledgeable Team of committed legal professionals. Clients trust us for our diligence and legally sound advisories and solutions coupled with high standards of professional and ethical practice. PROFESSIONAL SERVICES We have experience in multiple Domains spanning across all Courts and other quasi-judicial bodies and authorities created under special statutes, including but not limited to various Tribunals and Commissions. We cover nearly all areas in Litigation starting from Arbitration, Banking, Civil, Commercial, Construction, Corporate, Criminal, Insurance, Land, Labour, Matrimonial Laws to name some. Alternate Dispute Resolution We have expertise in resolving disputes via Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms including Arbitration, Mediation, Conciliation and Negotiations etc. to provide cost-effective and immediate solutions to our clients. We have a team of dedicated professionals who cater to our clients and represent them in various Fora pan India including before Delhi High Court Mediation and Conciliation Centre, Delhi International Arbitration Centre, other ad-hoc proceedings, etc. Audit & Compliance Management We have expertise in audit and compliance management under the provisions of various laws and rules/ regulations/ procedures applicable to the client. • We advise and guide our clients on the laws, regulations, statutory compliances and required governmental approvals etc. -

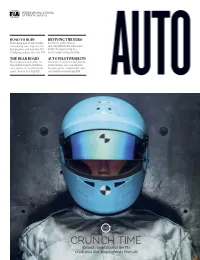

CRUNCH TIME Behind Closed Door at the FIA Crash Tests That Keep Formula One Safe

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: ISSUE #2 ROAD TO RUIN REVIVING THE EURO Travelling one of the world’s Formerly unloved and most dangerous highways in uncompetitive, the European Bangladesh and how the FIA Rally Championship has is helping reduce the risk P34 had a major makeover P62 THE BEAR ROARS AUTO PILOT PROJECTS From taking road safety to Once the stuff of science fiction, the global stage to building autonomous cars are close to new arenas for world motor becoming the comfortable and sport, Russia is rising P50 safe future of motoring P68 P42 CRUNCH TIME Behind closed door at the FIA crash tests that keep Formula One safe ISSUE #2 BEHIND THE SCENES THE FIA The Fédération Internationale In motor sport, the racing is de l’Automobile is the governing body of world motor sport and the just the tip of the iceberg, the federation of the world’s leading INTERNATIONAL motoring organisations. Founded culmination of months of JOURNAL OF THE FIA in 1904, it brings together 232 national motoring and sporting organisations from 134 countries, technical work to ensure both Editorial Board: representing millions of motorists JEAN TODT, NORMAN HOWELL, worldwide. In motor sport, car and driver have reached GERARD SAILLANT, RICHARD WOODS, it administers the rules and TIM KEOWN, DAVID WARD regulations for all international the highest standards. Editors-in-chief: four-wheel sport, including the FIA NORMAN HOWELL, RICHARD WOODS Formula One World Championship Executive Editor: MARC CUTLER and FIA World Rally Championship This is never more the case than where safety is Editor: JUSTIN HYNES concerned. -

Two-Year MBA IIM Udaipur's Flagship Master of Business Administration Letter from Auditor Batch Demographics

Summer Placement Report (Audited) 2019-21 Two-Year MBA IIM Udaipur's flagship Master of Business Administration Letter from Auditor Batch Demographics Women Students 23% 30% Non-Engineers November 5, 2020 in Batch Average Work Experience To The Director, Indian Institute of Management Udaipur Udaipur. 62% 27months Dear Sir, Students with Prior For Candidates with We hereby certify the attached Summer Internship Placement Report of the program of Work Experience Work Experience two years Master of Business Administration (MBA) - Batch 2019-21 of INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT UDAIPUR (IIMU). The Placement Report is the responsibility of IIMU. Our responsibility is to validate the information provided in the report with the relevant documents. The Placement Report is prepared in accordance with the Indian Placement Reporting Standards, Revision 2.2. We have obtained all information and explanations which to the best of our knowledge and belief were necessary for the purpose and we would further bring to your notice the following points. 1. The Report is based on the information and explanation provided by IIMU which includes copies of Placement Letters given by the recruiters, copies of Mails and other such communications received by IIMU in relation to the Placement. Educational Duration of Work Work Experience Background Experience by Sector 2. The validation of the information is based on the written communication received by IIMU from the recruiters. 4.60% 4.02% 5.17% 3.45% 5% 7% 10.34% 3.45% 3. We have verified the information with respect to Job Function, Locations and 11% 23% Stipends mentioned in the communications received from recruiters. -

Aerospace and Defence

Guide to MBA Recruitment in the… EXAMPLES Welcome to examples from the Top 100 MBA Recruiting Companies FTSE 100 Companies Global FTSE 100 Companies MBA Recruitment Guides Index Index Index Our standard guides are published Example 1 Example 1 Example 1 annually in October (in time for the start of Example 2 Example 2 Example 2 the school year) and then updated at the end of May. One Guide, the Top 100 Global MBA Recruiting Companies, is updated every 30 days and is automatically uploaded onto each schools page on our Top 100 Management Consulting FTSE Euro 100 Companies Top 100 Companies in Asia website. Deadlines which fall before our Companies publication date are emailed to subscribing schools - keeping you and your students Index Index Index aware of ongoing recruitment policies in Example 1 Example 1 Example 1 key companies worldwide. Example 2 Example 2 Example 2 Click on the hyperlinks under the guide of interest on the right-hand side to view the index pages and sample company profiles. Top 100 Marketing, Media, Advertising, Top 100 IT Companies Top 100 UK Biotech/Pharmaceutical PR and FMCG Companies Companies Index Index Index Example 1 Example 1 Example 1 Example 2 Example 2 Example 2 Top 100 Companies in the Gulf States Top 100 Companies in South America Top 100 Companies in India Index Index Index Example 1 Example 1 Example 1 Example 2 Example 2 Example 2 Workmaze Limited 15 St James Street Castle Hedingham Essex CO9 3EN UK. Registered in England: Company Registration No. 4100091 VAT No. 766 486 087. -

RBSA India Deals Snapshot March 2010-2

Mar 2010 Volume VI India Deals Snapshot Mergers & Acquisitions Update Acquirer Target Sector Stake Size SKIL Infrastructure Pipavav Shipyard Ltd Infrastructure 19.43% Rs 656.4 crore TRF Ltd Hewitt Robins International Industrial Goods NA $ 4.5 million Essar Group Aries’s coal mines Industrial Goods NA Undisclosed ArcelorMittal Uttam Galva Industrial Goods 4.90% Rs 75-80 crore Axis Bank Max New York Life Insurance BFSI 4.00% Undisclosed Company EdServ Softsystems Sparkling Minds IT / ITES NA Rs 1.25 crore Murugappa Group Cholamandalam DBS Finance Ltd BFSI 37.48% Rs 226.48 crore Hitachi Construction Telco Construction Equipment Industrial Goods 20.00% Rs 1,159 crore Company Company Teamlease Services Indian Institute of Job Training Service NA Undisclosed Crompton Greaves Ltd Power Technology Solutions Ltd Industrial Goods NA Undisclosed GVK Power & Infrastructure GVK Gautami Power Ltd Infrastructure 9.50% Undisclosed Ltd Aqua Logistics Ltd CIT Logistics Ltd; Logistics NA Undisclosed TAG Logistics Ltd; AGI Logistics Ltd Polaris Software Lab Ltd IndigoTX IT / ITES NA Undisclosed Bajaj Holdings & Investment Bajaj Electricals Industrial Goods 18.80% Rs 76.88 crore BCCL. Sanwaria Agro Oils Ltd Consumer Goods NA Rs 35 crore Hoechst GmbH AventisPharmaLtd Pharmaceutical 10.27% Rs 414.11 crore AT&T International Inc Tech Mahindra IT / ITES 8.70% $ 34.5 million Piramal Healthcare Ltd Cipla Pharmaceutical NA Rs 95 crore Jay Shree Tea & Industries M P Chini Industries Ltd Consumer Goods 100.00% Rs 112.5 crore Ltd Welspun Gujarat Stahl MSK Projects -

Model Request for Qualification for PPP Projects PROJECT

Development of MFC at Yeshwanthpur Railway Station Rail Land Development Authority MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS RAIL LAND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (RLDA) PROJECT INFORMATION MEMORANDUM FOR MULTIFUNCTIONAL COMPLEX AT YESHW ANT HPUR Model Rail Land Development Authority NearRequest Safdarjung for Railway Qualification Station, Moti Bagh -1 New Delhi – 110021 For PPP Projects Project Information Memorandum (PIM) Page 1 Development of MFC at Yeshwanthpur Railway Station Rail Land Development Authority DISCLAIMER This Project Information Memorandum (the “PIM”) is issued by Rail Land Development Authority (RLDA) in pursuant to the Request for Proposal vide to provide interested parties hereof a brief overview of plot of land (the “Site”) and related information about the prospects for development of multifunctional complex at the Site on long term lease. The PIM is being distributed for information purposes only and on condition that it is used for no purpose other than participation in the tender process. The PIM is not a prospectus or offer or invitation to the public in relation to the Site. The PIM does not constitute a recommendation by RLDA or any other person to form a basis for investment. While considering the Site, each bidder should make its own independent assessment and seek its own professional, financial and legal advice. Bidders should conduct their own investigation and analysis of the Site, the information contained in the PIM and any other information provided to, or obtained by the Bidders or any of them or any of their respective advisers. -

Karnataka 2013 the SILICON VALLEY of INDIA

MARCH Karnataka 2013 THE SILICON VALLEY OF INDIA For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org 1 MARCH Karnataka 2013 THE SILICON VALLEY OF INDIA Contents Karnataka – An Introduction Infrastructure Status Business Opportunities Doing Business in Karnataka State Acts & Policies For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org 2 MARCH Karnataka 2013 THE SILICON VALLEY OF INDIA Karnataka Factfile → Some of the prominent cities in the state are Ankola, Bengaluru, Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bidar, Bijapur, Chikmagalur, Chitradurga, Dandeli, Hubli-Dharwad, Mangalore, Mysore and Shimoga. → Karnataka has a tropical climate with three major seasons: warm and dry from February to May, monsoon from June to October and winter from November to January. Parameters Karnataka Capital Bengaluru Geographical area (sq km) 191,791 Administrative districts (No) 30 Population density (persons per sq Source: Maps of India 319 km)* → Karnataka is located in the Southern region of India. It Total population (million)* 61 is surrounded by the Arabian Sea in the West, Goa in Male population (million)* 31 the Northwest, Maharashtra in the North, Andhra Pradesh in East, Tamil Nadu in the Southeast, and Female population (million)* 30 Kerala in the Southwest. Sex ratio (females per 1,000 males)* 968 Literacy rate (%)* 75.6 → Languages spoken are Kannada, Tulu, Kodava, Hindi and English. Sources: Economic Survey of Karnataka 2011-12, *Provisional Data – Census 2011 For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org KARNATAKA – AN INTRODUCTION 3 MARCH Karnataka -

Beer and Spirits)

Success story of Billionaire & Business Tycoon Vijay mallya, Chairman of United Breweries Group, Kingfisher Airlines, Force India F1 Team, Royal Challengers, East Bengal FC ..... Born on 18 December 1955 (1955-12-18) in Kolkata, India Occupation Chairman of : United Breweries Group, Kingfisher Airlines, Force India F1 Team, Royal Challengers Bangalore & East Bengal FC Education Degree in Commerce form Kolkata University Dr. Vijay Mallya is a Bangalore - based billionaire businessman and Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha since 2002) from India. He is the son of a famous industrialist Vittal Mallya and is the chairman of the United Beverages Group . The UB Group is one of India's largest conglomerates with annual sales of over US$ 4 billion and a market capitalization of approximately US$ 12 billion. The Group has diverse interests in brewing, distilling, real estate, engineering, fertilizers, biotechnology, information technology and aviation. It is also the largest Indian manufacturer of beverage alcohol (beer and spirits). He also owns the Formula One team Force India, the Indian Premier League team Bangalore Royal Challengers, and the I-League team East Bengal FC Personal life Mallya born in a Konkani Gaud Saraswat Brahmin family originally from the town of Bantwal (near Mangalore) in Karnataka. He is the son of Vittal Mallya and Lalitha Ramaiah. He was educated at La Martiniere Boys' College, Kolkata and completed his degree at St. Xavier's College, Calcutta under Calcutta University. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Business Administration by the California Southern University Career Mallya worked for the American Hoechst Corporation (now Sanofi-Aventis) in the US and with Jenson & Nicholson in the UK. -

United Breweries Limited Conference Call

“United Breweries Limited Q2 FY 2015 Earnings Conference Call” November 13, 2014 ANALYST: MR. HARIT KAPOOR – IDFC SECURITIES MANAGEMENT: MR. HENRICUS P. VAN ZON – CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER – UNITED BREWERIES LIMITED MR. P. A. POONACHA – DIVISIONAL VICE PRESIDENT - FINANCE AT UNITED BREWERIES LIMITED Page 1 of 14 United Breweries Group November 13, 2014 Moderator: Ladies and Gentlemen, good day and Welcome to United Breweries Q2 FY 2015 Earnings conference call, hosted by IDFC Securities Limited. As a reminder, all participant lines will be in the listen-only mode, and there will be an opportunity for you to ask questions after the presentation concludes. Should you need assistance during the conference call, please signal an operator by pressing “*” then “0” on your touchtone telephone. Please note that this conference is being recorded. I now hand the conference over to Mr. Harit Kapoor from IDFC Securities. Thank you and over to you Mr. Kapoor! Harit Kapoor: Very good afternoon to everybody. On behalf of IDFC Securities, I would like to welcome you all for to the Q2 FY 2015 Conference Call of United Breweries. We have representing the senior management of United Breweries, Mr. Henricus P. Van Zon, CFO as well as Mr. Poonacha. I would like to now handover to the senior management to make their comment, which we will be followed by Q&A. Over to you, Sir! Henricus P. Van Zon: Thank you very much Mr. Kapoor. Ladies and gentlemen, all very much welcome to this telephone conference regarding the results that we have published this morning. Let us start with stating that we indeed had a very good quarter the Q2. -

The United Breweries Group

The United Breweries Group Based in Bangalore, it is a conglomerate of different companies with a major focus on the brewery (beer) and alcoholic beverages industry. The company markets most of its beer under the Kingfisher brand and has also launched Kingfisher Airlines, an airline service in India, with international flights operating recently. It is also present in the sporting industry by the way of buying a team in the Indian Premier League (cricket) from their hometown i.e. Bangalore by the name of Bangalore Royal Challengers. The group has also made India’s first team entry into Formula One by being the joint owner team Force One (India’s first-ever Formula One Team) with the Netherlands based Mol Family. United Breweries is India's largest producer of beer with a market share of around 48% by volume. The group is a multi-faceted conglomerate with business interests in Beverage Alcohol, Pharmaceuticals, Media, International Trading, Aviation, Fertilizer, Research & Development, and Infrastructure Development. After Vittal Mallya's death in 1983, his son Vijay Mallya assumed the mantle of the group. Vijay Mallya inducted professional management and consolidating the Group into individual operating divisions. In 1988, UB Group acquired the global Berger Paints Group with operating companies across four continents. The paints business was divested for significant value in 1996. After India adopted economic liberalization in 1991, the UB Group decided to retain interests in only those businesses that were globally competitive and did not depend upon fiscal tariff protection. Today, UB Group is the third largest manufacturer of Spirits products in the world. -

Press-Release-23

India Abroad December 6, 2013 BUSINESS A27 Silicon Valleys new flag bearers for new drug molecules and also medical soft- ware-related patents, but the focus is on bio- pharmaceuticals, bio- chemistry, medical de- vices and drugs. Kadambi hopes to help applicants cut down on time needed to get a patent. Claim- ing that though the minimum patent award time was three- and-a-half months, people often had to wait for years, she said, Alok Bhatia, second from left, receives the Entrepreneur award at the Silicon Valley Awards in I have got 30 patents California. Ankit Shah, second from left, receives the Technology award. in three years. She also hoped that RITU JHA continue to do well in entrepreneurship. Jaspreet OBeroi of Chaats & Currys, Su- the award would get her message across to On the sidelines of the event he discussed nnyvale, California, also won in the Entre- other entrepreneurs: You dont have to be he Silicon Valley Awards 2013, themed placements at information technology com- preneur category. I have always followed my stuck to one thing... Go cross functional Making a Difference, awarded seven panies; his company has placed over 1,200 passion. Receiving this award made me feel because no science is a pure science any Tpeople in the fields of technology, consultants working at various client loca- so proud that there are people who appreci- more. Everything is integrated, be it elec- entrepreneurship, media and nonprofit in tions like Wells Fargo, Ebay, GAP and Bank ate my work and talent, she said. tronics, be it medical devices, be it pharma- California November 17.