Mystery of Creation in Rabbinic Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IA * \!-J %X" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> International Journal for Pastors September 2004 a L,.1 T.©J/"©"> IA * \!-J %X

International Journal for Pastors September 2004 A L,.1 T.©j/"©"> IA * \!-j %X_,. Is the Genesis Creation account literal? Amid the far-reaching, contemporary shifts occurring in significant Christian circles, what are the implications of dismissing the Genesis Creation epic as a literal account of how the present world order began? Norman R. Gulley f-\ Sexual misconduct in ministry: victims and wounds 1 The fifth in Ministry©s series on ministers and Ftowers, K-fehad Hasel Roland Hegsted, Kathteen Kuntaraf, Ekteharelt Muelier, Jan Pautoi, Robert Peach, sexual wrongdoing Aogzl Man*) ttorirtguez, Penny Shaft "WSSam Shea, Miroslav Kis Zinte Pastoral Assistant Editors: John C. Cress, Fredrfck Preaching beyond modernism (part 2) Russeft, Maybn Scburch, L«-«n Seitwki ©©,, taternatfwat Advisors: AtejarKtroBulton.fohn © : How must preaching change as many world cultures ten Manafchi©Zac^weus©fewfieftiJ, GqbM Msuw, move into seriously different ways of thinking and te» Omwa, Qarid Ostaame, ©Peter ftaawfel*, viewing the world? Pastoral Advtsors: lesfe Baumgartner, S. Peter Gerhard van Wyk and Rudolph Meyer Ministering in the midst of competing A<Jv«rtfaiog Editorial Office worldviews -«W«»»©**^;-;_;;;v-;; ;;;_ What remains the same and what changes in ministry C«*$» Photo GeBy tmag«s Pssigti* , as we seek to reach out to a changing world? Cover Design Harty Kw» ,.,,,. Trevor O©Reggio Subscriptions: 1 2 © issues: United States USS2R.99; Canada arW overseas ,US$S1, 99; airmail VS$41, 75; The stripping process: broken down for breakthrough A powerfully honest story of personal growth in Circulation queries, renewals, new subscriptions, ministry: Year of World Evangelism feature address xhatigejii le^il: riwWSPS©.adWBti^Srg phon«: 501-« 0.&S10; fax J01-680-6S02, Fredrick Russell with name, address, telephone and fax numbers, and The shape of the emerging church: Sodat Security nufnber (if U.S. -

Half the Story

HALF THE STORY WHY COVENANT SONSHIP RESTS ON ONTOLOGICAL SONSHIP A Pre-publication Review of Ty Gibson’s ‘The Sonship of Christ’ through a series of emails and a prequel to ‘Trialogue’ By Brendan Valiant Introduction This document is not intended for widespread circulation. I am making it available only on request as people have learned about it through the Trialogue video. However, in case this does get shared, some context is appropriate to fully appreciate this document. This document contains a series of emails with Ty Gibson prior to the publication of his book “The Sonship of Christ: Exploring the Covenant Identity of God and Man”. The introduction was made by our mutual friend and colleague in Christ, David Asscherick in 2018. Ty had before that time only presented his manuscript to favourable reviewers, those who already agreed with him on the subject matter. It was an opportunity for him to have a truly objective appraisal of the content and he welcomed it. Through this process, a respect and friendship between Ty and myself was forged. Word about this review process got out to the editors of Adventist Review TV (ARTV) who asked if they could make a documentary of our discussions as part of their “Deeper” series. This culminated in mid- 2018 and was titled “Trialogue” and can be found at the link below: https://www.artvnow.com/digging-deeper/season:1/videos/trialogue-v4 The content in this review only constitutes one side of an interaction. It can only be complete when reading Ty Gibson’s book. -

In This Issue

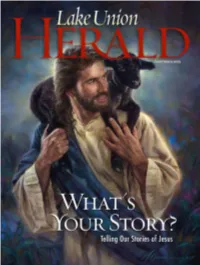

“Telling the stories of what God is doing in the lives of His people” 14 This month’s cover, “The Good Shepherd,” is a Nathan Greene painting. His artwork can be seen at www.hartclassics.com. © Hart Classics, all rights reserved. in every issue... in this issue... 3 President’s Perspective One day we will cast our crowns at the feet of the One who stooped to 4 New Members take our place so we might have the abundance of joy. Spontaneous and 6 Youth in Action unsuppressed, our response of gratitude springs forth to the One who created 7 Beyond our Borders us, loves us, emptied Himself and gave Himself to us. Until then, we can’t help 8 Family Ties but share our stories with those around us—to tell them the 9 Healthy Choices good news that the One who loved us loves them, too. 10 Extreme Grace The articles in this issue reflect the hearts of those who 11 Conversations with God have already begun to sing their song of eternity, “Redeemed, how I love to proclaim it!”1 12 Sharing our Hope 13 ConeXiones Gary Burns, Editor 22 AMH News 23 Andrews University News 1. Crosby, Fanny. “Redeemed, How I Love to Proclaim It.” Lyrics. Songs of Redeeming Love. John J. Hood, 1882. 24 News 29 Mileposts 30 Classifieds features... 34 School Notes 14 Tell ‘The Story’ by Connie Vandeman Jeffery 17 God’s Remnant Tapestry by Shirley S. Holmes 36 Announcements 20 My Confidence in Our Creator Godby David Steen 37 Partnership with God 38 One Voice The Lake Union Herald (ISSN 0194-908X) is published monthly by the Lake Union Conference, P.O. -

Retire to Collegedale, Tennessee's Adventist

“Telling the stories of what God is doing in the lives of His people” 14 This month’s cover, “The Good Shepherd,” is a Nathan Greene painting. His artwork can be seen at www.hartclassics.com. © Hart Classics, all rights reserved. in every issue... in this issue... 3 President’s Perspective One day we will cast our crowns at the feet of the One who stooped to 4 New Members take our place so we might have the abundance of joy. Spontaneous and 6 Yo uth in Action unsuppressed, our response of gratitude springs forth to the One who created 7 Beyond our Borders us, loves us, emptied Himself and gave Himself to us. Until then, we can’t help 8 Family Ties but share our stories with those around us—to tell them the 9 Healthy Choices good news that the One who loved us loves them, too. 101 Extreme Grace The articles in this issue reflect the hearts of those who 11 Conversations with God have already begun to sing their song of eternity, “Redeemed, 1 121 Sharing our Hope how I love to proclaim it!” 131 ConeXiones GaryGary Burns,Burn Editor 222 AMH News 233 Andrews University News 1. Crosby, Fanny. “Redeemed, How I Love to Proclaim It.” Lyrics. Songs of Redeeming Love. John J. Hood, 1882. 2244 News 292 Mileposts features... 303 Classifieds 343 School Notes 14 Tell ‘The Story’ by Connie Vandeman Jeffery 17 God’s Remnant Tapestry by Shirley S. Holmes 363 Announcements 20 My Confidence in Our Creator God by David Steen 373 Partnership with God 383 One Voice The Lake Union Herald (ISSN 0194-908X) is published monthly by the Lake Union Conference, P.O. -

Families First Vantage Point

June 2009 SOUTHERN Families First Vantage Point Our Neighborhood Bible Study “Visit your neighbors and show an interest in the salvation of their souls .... Tell those whom you visit that the end of all things is at hand. The Lord Jesus Christ will open the door of their hearts and will make upon their minds lasting impressions .... Tell them how you found Jesus and how blessed you have been since you gained an experience in His service .... Tell them of the gladness and joy that there is in the Christian life” Testi- monies for the Church, Vol. 9, p. 38. Friday evening, March 27, 2009, Cheryl and I walked up our driveway to begin visiting everyone in our neighborhood. We’ve been praying for our neighbors, we’ve walked and jogged in our neighborhood, we’ve become acquainted with some of our neighbors, we’ve waved at our neighbors, but I must admit we had not yet visited all our neighbors. We knocked on every door — about 70 homes. Most people were home, and all were cordial as we introduced ourselves as neighbors up the street. We gave each one a special invitation inviting them to a neighborhood Bible study in our home to begin April 17. Once we got started we gained courage, and we knew the outcome was entirely up to God. We prayed every day that God would impress some of our neighbors to come. On Friday evening, April 17, the house was ready, the Bible study lesson was ready, and we were ready to open our home to our neighbors. -

Vol. 191, No. 3

January 23, 2014 Vol. 191, No. 3 www.adventistreview.org January 23, 2014 adventist survives home Invasion 12 Into all the World 22 When a Vandal slashed My Tires 29 Head subhead Key Adventures: Archaeological Expeditions to Biblical Sites Key Adventures Cradle of Mankind (Turkey) Noah and the Ark, Abraham and Jacob – we all know these sto- ries from our childhood. And where did these stories take place? Serious archaeologists do agree: The crad- le of civilization lies in Mesopotamia. A coincidence? Why not come along and make up your own mind! Amazing Adventures invites you – to a part of Tur- key that hardly anyone knows. Date: May 7-16, 2014 Prices: EUR 1,590 (approx. USD 2,170) www.amazing-adventures.ch/ cradle-of-mankind Bible cruise „We feel so blessed that we had the opportunity to go on the Lycian Coast (Turkey) wonderful Revelation cruise.“ The Quran – proper material for Christi- T. and B. O. ans? What pictures come to mind with the word „Islam?“ We invite you to „I think this was the most stress-free trip I‘ve ever taken: lots of experience Islam on location, while at interesting people to talk with and get to know, yummy food, the the same time stocking up on sunshine, boats and bikes, the historic sites--it was the first trip I‘ve taken peace and quiet and restoring your zest where I didn‘t have to worry about finding a place to stay. It was for life far off the beaten track. Sylvain also nice to not have to worry about where to eat, what to see, Romain, Seventh-day Adventist pastor etc. -

Unit 10.2A Jesus: Messages from His Heart Series God’S Heart

UNIT 10.2A JESUS: MESSAGES FROM HIS HEART SERIES GOD’S HEART Copyright © 2017 by Adventist Encounter Curriculum. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. Special thanks to the Biblical Research Institute for their feedback and guidance on this material. THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scriptures taken from the New Century Version. Copyright © 1987, 1988, 1991 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Scripture quotations marked (NLT) are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation. Copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Scripture quoted from NASB are from The New American Standard Bible®. Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved. God’s Word® is a copyrighted work of God’s Word to the Nations. Copyright © 1995 by God’s Word to the Nations. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Quotations designated (NET) are from the NET Bible®. Copyright ©1996-2006 by Biblical Studies Press, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Used by permission. This curriculum is a collaborative initiative of the Education Departments of Australian Union Conference, New Zealand Pacific Union Conference, and the North American Division. -

3ABN World Downpour of Rain Halted Plans for an Most of Us Today Despair of Ever Handling All 3ABN World Is a Monthly Publication

News • inspiration • Special Features • Program schedules 3abn.org January 2008 A woman’s commitment to quietly “wait on the Lord” K elly Mowrer The Story Behind the Smile page 6 Kelly Mowrer, Host of Praise! and His Words Are Life CONTENTS Testimony: Praise report: 16 Jesse’s Wish 21 New Station in Shasta Valley CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S LETTER s a new year begins, we can’t help but look forward to the blessings our gracious God I Believe In Miracles Ahas in store for us. Each day we’re inspired to do even more for Him. ecently, Dan Houghton, president of Hart Research Foun- But what more can we do for the Lord? It’s a new dation, called to tell us that while cleaning out a storage ISSN 1552-4140 year, and the perfect time for introspection. building, he had found the original master cassette tape Executive Editor Mollie Steenson R This month you’ll read about the different ways in Managing Editor Bobby Davis that he had used to record a young Danny Shelton as he spoke to which people share their love for Christ. Kelly Mow- Creative Director Michael Prewitt the Adventist-laymen’s Services and Industries (ASI) Convention at rer shares through her music; Jesse and Kimberly Design Assistant Adam Dean Big Sky, Montana, in 1985! Danny was not scheduled to be on the Photographer Kenton Rogers James share through their personal testimony; and a Copyeditors Barbara Nolen program, and had actually been told small group of dedicated “mountain men” work hard J. D. Quinn so in no uncertain terms! But a sudden This network is truly to share Jesus through new television stations! About 3ABN World downpour of rain halted plans for an Most of us today despair of ever handling all 3ABN World is a monthly publication. -

ARISE Handbook 2021

2022 STUDENT HANDBOOK AUSTRALIA EDITION Experience the story. Make disciples. February 7 – May 7 LIGHTBEARERS.ORG/ARISE Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S INSIDE ARISE 4 Hello Why We Exist GET WITH THE PROGRAM 6 The Way It Works The Story Outreach Other Components THE STORY CURRICULUM 10 The Story The Telling Biblical Doctrines OUR TEAM AND INSTRUCTORS 13 Who We Are Core Team 2022 Instructors STUDENT LIFE 15 CAMPUS Life Personal Life Everyday Life APPLICATION DETAILS 18 The Process The Money Part RESOURCE LIST 21 Books You’ll Need FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 Things That Get Asked a Lot TAKE YOUR NEXT STEP 26 Make Your Move ARISE ARISE HELLO So you’re considering ARISE? Awesome. Maybe you heard about us from your pastor, a friend, the internet, or your brother- in-law’s second cousin who spoke at a church conference last year. Regardless of how the idea got into your head, we’re excited that God might be leading you in our direction. Maybe you already know where your life is headed. Maybe you don’t. Either way, we believe God has a beautiful story for your life and it's found in Scripture: you were meant to be a disciple-maker. No matter what career you choose—pastor, poet, plumber—Jesus has called all His followers to be disciple-making disciples. The inclosed information is designed to give you a clear picture of what ARISE is all about. If you still have questions after reading, please don’t hesitate to contact us directly. We’re excited about the possibility of you joining our program. -

Journey to the Promised Land

ADRIAN WELSH Prophetic Parallels - Journey to the Promised Land Copyright © 2010 by Adrian Welsh All rights reserved Cover design by Adrian Welsh All Scripture quotations are from the King James Version (KJV) unless otherwise stated. All quotations from Ellen White were taken from the Ellen G. White Writings, Comprehensive Research Edition 2008 CD. This book may be freely copied, so long as it is not sold and is kept in its original form. If you would like your own copy, you can write to: [email protected] or Prophetic Parallels PO Box 602 Maleny, QLD 4552 Australia Further information can be found at: www.propheticparallels.com Dedicated to: God’s amazing grace and patience & Linda, my loving and patient wife Table of Contents Preface................................................................................. 1 1. Chosen of God............................................................... 2 2. Out of Egypt................................................................ 13 3. Go Forward.................................................................. 23 4. The Appointed Sign ......................................................37 5. Has the Lord Led Us?................................................... 46 6. Organized..................................................................... 53 7. Opposition................................................................... 66 8. Rebellion at Kadesh..................................................... 75 9. An Uprising................................................................ -

When God Answers the Phone

Adventist heAlth speciAl edition Northwest Adventists in Action OCTOBER 2009, Vol. 104, No. 10 Adventist heAlth: Sacred Work when god AnswersWhen God answersthethe phone phone www.GleanerOnline.org Images of Creation “ ut my eyes are fixed on you, O Sovereign LORD; in you I take refuge ... ” Psalm 141:8 (NIV) “Face of a Saw-whet Owl” by Michael Woodruff of Spokane, Washington. B In this issue Feature Editorial 4 To Serve is to Love 5 Did You Know? 16 World News Briefs ACCION 18 Hermiston en Accion News 19 Alaska 20 Idaho 21 Montana 22 Oregon 26 Upper Columbia 31 Washington 34 Walla Walla University FYI 35 /2D3<B7AB 6 3 / :B6A>317 / :327B7=< N o rth w esA t d v en stin A coti n 36 Family Healthy Choices 39 SEPTEMBER 2009 , Vol. 104, No. 6 9 40 Announcements Beyond the X-ray equipment, operating rooms 42 Advertisements and IV’s, Adventist Health workers believe their / 2 D 3 < B 7 A B 6 3 E63<5=2/:B6(Sacred Work main business is Sacred Work.” Read why in /<AE3@A���� G�� Let’s Talk � � �B63>6=<3 � 50 The Project this month’s feature beginning on page 6. � ����� w w w . G l e a n e r O n l i n e . o r g 12 October 2009, Vol. 104, No. 10 GLEANER STAFF Published by the North Pacific Union SUBMISSIONS—Timely announcements, features, news stories and Editor Steven Vistaunet Conference of Seventh-day Adventists® family notices for publication in the GLEANER may be submitted directly Managing Editor Cindy Chamberlin to the copy coordinator at the address listed to the left. -

Reading Tidings of the Southern Union Adventist Family

March 2007 SOUTHERN Spreading Tidings of the Southern Union Adventist Family Dreams Come True on Adventist7 It’s My Very OwnCampuses 21 Remembering the Morning Star 25 Follow Your Heart ... Vantage Point The Value of a Christian Education My father has a memory from his early childhood of the house he lived in being pulled down a country road in North Dakota by two large steam engines that were normally used to harvest the wheat. The dirt road was wet from rain and, at one point in the journey, was not able to hold the weight of the engines, which then sank into the mud. Finally after many hours, they were able to complete the task of moving the house to a new location. Dad was too young to remember much about why the house was being moved, but later learned firsthand about his parents’ commitment to Christian education. It so hap- pened that the first farm that they homesteaded in North Dakota was too far from the church and school where the nine Bietz children could be educated, and so they found property closer to the school and moved the house. Christian education was fundamental to the convictions of my grandfather and grand- mother because they read a book by Ellen G. White that had recently been translated into German. The book was titled Education. A Legacy of Sacrifice While few people would pick up their house and move it so their children could be educated in a Seventh-day Adventist environment, I am inspired by the stories I’ve heard of students who have made similar sacrifices.