Creating a Board Game to Influence Student Retention and Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escape Rooms for Learning

Abstracts of Papers Presented at the 12th International Conference on Game Based Learning ECGBL 2019 Hosted By University of Southern Denmark Odense, Denmark 3-4 October 2019 Copyright The Authors, 2019. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission may be made without written permission from the individual authors. Review Process Papers submitted to this conference have been double-blind peer reviewed before final acceptance to the conference. Initially, abstracts were reviewed for relevance and accessibility and successful authors were invited to submit full papers. Many thanks to the reviewers who helped ensure the quality of all the submissions. Ethics and Publication Malpractice Policy ACPIL adheres to a strict ethics and publication malpractice policy for all publications – details of which can be found here: http://www.academic-conferences.org/policies/ethics-policy-for-publishing-in-the- conference-proceedings-of-academic-conferences-and-publishing-international-limited/ Conference Proceedings The Conference Proceedings is a book published with an ISBN and ISSN. The proceedings have been submitted to a number of accreditation, citation and indexing bodies including Thomson ISI Web of Science and Elsevier Scopus. Author affiliation details in these proceedings have been reproduced as supplied by the authors themselves. The Electronic version of the Conference Proceedings is available to download from DROPBOX https://tinyurl.com/ECGBL19 Select Download and then Direct Download to access the Pdf file. Free download is -

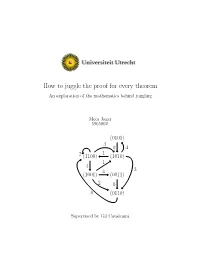

How to Juggle the Proof for Every Theorem an Exploration of the Mathematics Behind Juggling

How to juggle the proof for every theorem An exploration of the mathematics behind juggling Mees Jager 5965802 (0101) 3 0 4 1 2 (1100) (1010) 1 4 4 3 (1001) (0011) 2 0 0 (0110) Supervised by Gil Cavalcanti Contents 1 Abstract 2 2 Preface 4 3 Preliminaries 5 3.1 Conventions and notation . .5 3.2 A mathematical description of juggling . .5 4 Practical problems with mathematical answers 9 4.1 When is a sequence jugglable? . .9 4.2 How many balls? . 13 5 Answers only generate more questions 21 5.1 Changing juggling sequences . 21 5.2 Constructing all sequences with the Permutation Test . 23 5.3 The converse to the average theorem . 25 6 Mathematical problems with mathematical answers 35 6.1 Scramblable and magic sequences . 35 6.2 Orbits . 39 6.3 How many patterns? . 43 6.3.1 Preliminaries and a strategy . 43 6.3.2 Computing N(b; p).................... 47 6.3.3 Filtering out redundancies . 52 7 State diagrams 54 7.1 What are they? . 54 7.2 Grounded or Excited? . 58 7.3 Transitions . 59 7.3.1 The superior approach . 59 7.3.2 There is a preference . 62 7.3.3 Finding transitions using the flattening algorithm . 64 7.3.4 Transitions of minimal length . 69 7.4 Counting states, arrows and patterns . 75 7.5 Prime patterns . 81 1 8 Sometimes we do not find the answers 86 8.1 The converse average theorem . 86 8.2 Magic sequence construction . 87 8.3 finding transitions with flattening algorithm . -

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence Jose Barambones1, Ali Abavisani1, Elena Villalba-Mora1;2, Miguel Gomez-Hernandez1;3 and Xavier Ferre1 1Center for Biomedical Technology, Universidad Politecnica´ de Madrid, Spain 2Biomedical Research Networking Centre in Bioengineering Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), Spain 3Aalborg University, Denmark Keywords: Gamification, Serious Games, Exergames, Elderly, Frailty, Discussion. Abstract: Gamification and Serious games techniques have been accepted as an effective method to strengthen the per- formance and motivation of people in education, health, entertainment, workplace and business. Concretely, exergames have been increasingly applied to raise physical activities and health or physical performance im- provement among elders. To the extend of our understanding, there is an extensive research on gamification and serious games for elderly in health. However, conducted studies assume certain issues regarding context biases, lack of applied guidelines or standardization, or weak results. We assert that a greater effort must be applied to explore and understand the needs and motivations of elderly players. Further, for improving the impact in proof-of-concept solutions and experiments some well-known guidelines or foundations must be adopted. In our current work, we are applying exergames on elderly with frailty condition in order to improve patient engagement in healthcare prevention and intervention. We suggest that to detect and reinforce such traits on elderly is adequate to extend the literature properly. 1 INTRODUCTION preserve the intrinsic capacity of the individual, its en- vironmental characteristics and their interaction. In In recent years, a rapid increase of consumer soft- parallel, by 2050 life expectancy will surpass 90 years ware inspired by the video-gaming has been per- and one in six people in the world will be over age 65 ceived. -

Thursday Friday

3:00 PM – 4:00 PM Thursday 4:00 PM – 5:00 PM 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM “Hannibal and the Second Punic War” “The History of War Gaming” Speaker: Nikolas Lloyd Location: Conestoga Room Speaker: Paul Westermeyer Location: Conestoga Room Description: The Second Punic War perhaps could have been a victory for Carthage, and today, church services and degree Description: Come learn about the history of war gaming from its certificates would be in Punic and not in Latin. Hannibal is earliest days in the ancient world through computer simulations, considered by many historians to be the greatest ever general, and focusing on the ways commercial wargames and military training his methods are still studied in officer-training schools today, and wargames have inspired each other. modern historians and ancient ones alike marvel at how it was possible for a man with so little backing could keep an army made 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM up of mercenaries from many nations in the field for so long in Rome's back yard. Again and again he defeated the Romans, until “Conquerors Not Liberators: The 4th Canadian Armoured Division in the Romans gave up trying to fight him. But who was he really? How Germany, 1945” much do we really know? Was he the cruel invader, the gallant liberator, or the military obsessive? In the end, why did he lose? Speaker: Stephen Connor, PhD. Location: Conestoga Room Description: In early April 1945, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division 5:00 PM – 6:00 PM pushed into Germany. In the aftermath of the bitter fighting around “Ethical War gaming: A Discussion” Kalkar, Hochwald and Veen, the Canadians understood that a skilled enemy defending nearly impassable terrain promised more of the Moderator: Paul Westermeyer same. -

THE BENEFITS of LEARNING to JUGGLE for CHILDREN Written by Dave Finnigan

THE BENEFITS OF LEARNING TO JUGGLE FOR CHILDREN Written by Dave Finnigan Fitness, Motor Skills, Rhythm, Balance, Coordination Benefits . Students can start acquiring pre-juggling skills in pre-school and kindergarten by learning to toss and catch one big, colorful, slow-moving nylon scarf. Once tossing and catching becomes routine, you can use one nylon scarf anywhere that you would normally use a ball or beanbag for most games and many individual challenges. Just think of the scarf as a "ball with training wheels." Scarf juggling and scarf play progresses in a step-by-step manner from one, to two, and on to three. Scarf play and scarf juggling requires big, flowing movements. Children get a great cardio-vascular and pulmonary work-out when they juggle scarves, exercising the big muscles close to the head and close to the heart. They will find scarf juggling to be a great deal of work and lots of fun at the same time. Once they move on to beanbags or other faster moving equipment, they get exercise not only from tossing, but from bending over to pick up errant objects as well. Once a student can juggle continuously, they can "workout" with heavy or bulky objects such as heavyweight beanbags, basketballs, or other items which provide strenuous exercise while they improve focus and dexterity. Because all of this tossing and catching activity can be done to music, you can use different types of music to help children acquire a sense of rhythm and a natural "beat." By working together, students can participate in a group activity requiring concentration and attention to task and reinforcing rhythm. -

Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 10 | Issue 2 July 2020 Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling Ceire Monahan Montclair State University Mika Munakata Montclair State University Ashwin Vaidya Montclair State University Sean Gandini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Monahan, C. Munakata, M. Vaidya, A. and Gandini, S. "Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 10 Issue 2 (July 2020), pages 291-314. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.202002.14 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol10/iss2/14 ©2020 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling Ceire Monahan Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University, New Jersey, USA -

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers' Perspectives

Drivers and Barriers to Adopting Gamification: Teachers’ Perspectives Antonio Sánchez-Mena1 and José Martí-Parreño*2 1HR Manager- Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain and Universidad Europea de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain 2Associate Professor - Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts and it is gaining momentum in a wide range of areas including education. Despite increasing academic research exploring the use of gamification in education little is known about teachers’ main drivers and barriers to using gamification in their courses. Using a phenomenology approach, 16 online structured interviews were conducted in order to explore the main drivers that encourage teachers serving in Higher Education institutions to using gamification in their courses. The main barriers that prevent teachers from using gamification were also analysed. Four main drivers (attention-motivation, entertainment, interactivity, and easiness to learn) and four main barriers (lack of resources, students’ apathy, subject fit, and classroom dynamics) were identified. Results suggest that teachers perceive the use of gamification both as beneficial but also as a potential risk for classroom atmosphere. Managerial recommendations for managers of Higher Education institutions, limitations of the study, and future research lines are also addressed. Keywords: gamification, games and learning, drivers, barriers, teachers, Higher Education. 1. Introduction Technological developments and teaching methodologies associated with them represent new opportunities in education but also a challenge for teachers of Higher Education institutions. Teachers must face questions regarding whether to implement new teaching methodologies in their courses based on their beliefs on expected outcomes, performance, costs, and benefits. -

What's Happening at the IJA ?

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION October 2007 IJA e-newsletter editor: Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http://www.juggle.org/renew What’s Happening at the IJA ? In This Issue: 2008 Lexington IJA Festival Help Wanted Have You Moved, or Gotten a New Email Address? Treasury Remember, the only way to ensure that you don't miss a World Juggling Day single issue of JUGGLE magazine is to give us your new Marketing the IJA address. The USPS will generally not forward JUGGLE Joggling Record magazine. Insurance To update your mailing address, email, or phone, please Regional Festivals send email to [email protected] or call TurboFest - Quebec City 415-596-3307 or write to: IJA, PO Box 7307, Austin, TX 78713-7307 USA. World Circus Year 2008 IJA Festival, Lexington, Kentucky The Hyatt is connected to the convention center. The convention center has a food court and shops and they are Lexington Notes by Richard Kennison open on a daily basis. There is a vibrant downtown area right Everyone, around the convention center. I just spent two days in Lexington, KY. I am very thrilled to tell The convention center contact person, the hotel contact person you that I think it is a wonderful site. I will not go into long and the theatre contact person are all professional and excited details here but: that we are coming. Bond Jacobs—the visitors bureau contact You can park your car (for free if you stay the the Hyatt) and person is an asset and will go the extra mile for us. -

Coin Master Hack Apk Download 2021

Coin Master Hack Apk Download 2021 Coin Master Hack Apk Download 2021 CLICK HERE TO ACCESS COIN MASTER GENERATOR Phishing is the fraudulent attempt to obtain sensitive information or data, such as usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, or other sensitive details by impersonating oneself as a trustworthy entity in a digital communication. Typically carried out by email spoofing, instant messaging, and text messaging, phishing often directs users to enter personal information at a fake website which ... Coin Master 99k Spins - Working Coin Master Mod APK & Hack & Cheat 2021. #236 Магазин на проверку - dmarket.com (ТОРГОВАЯ ПЛОЩАДКА СКИНОВ КСГО) ПРОДАЖА И ПОКУПКА СКИНОВ! free spin link coin master app Players can download Coin Master by visiting the Google Play app store. Or simply search it on the search engine. However, the Coin Master MOD (Unlimited Coins, Spins) version will not be officially released. Players who want the experience need to install it manually using the APK file. coin master facebook Mini World is a 3D free-to-play sandbox game about adventure, exploration, and creating your dream worlds. See Also. Ele deve lutar contra os gângsteres de rua, vagabundos e máfias para caminhar sua casa. Naruto Mobile hack mod apk with cheat . 3 promises you intense and spectacular battles. hack coin master free spins coin master hack app ios All Free Spins and Coins we send into your Coin Master account via private servers and are 100% untraceable! Very similar to the free spins links provided through their social media pages, Coin Master will send you links to free gifts of coins, spins and more. -

Fargo Convention Well Worth the Journey

August 1980 Vol. 32 No. 5 Membership—1,200 1981 Convention Site—Cleveland, OH, Case Western Reserve University Fargo convention well worth the journey In anticipation of sharing talent and watching jugglers in the crowded party room witti the promise Benefit shows for crowds at the NDSU student some of the best jugglers in North America at work, of greater support if the IJA would return to Fargo union, the Red River Mall, a Shrine club and a 475 people trekked through mid July heat to Faigo, nextyear. Reaction was not positive, and conven- nursing home demonstrated IJA’s appreciation ND, site of the 33rd IJA annual convention, tioneers later voted Cleveland. OH, as the 1981 for the hospitality, There, close by the geographical center of the site (see page 6). The convention ran smoothly, and largely on time. continent, they witnessed the basics—like 3-ball High-rise lodging contained two-story foyer areas and 5-club cascades—and the outer limits of jug that were ideal for juggling. The university food gling skill, as demonstrated by Michael Kass’s prize service fed 165 jugglers three times day, and cater winning performance of club kick-ups. The same ed a pleasant outdcxar "buffalo" barbeque at Troll- lure of communion with fellow jugglers has drawn wood Park on Saturday. this group together annually since 1947, when The Saturday morning parade included many the founding fathers formed the group during a other area groups, and was aired by NBC news convention of the international Brotherhood of on a late-night broadcast. -

A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames

Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2017 How Effective Is “Exergamification”? A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames Amir Matallaoui Jonna Koivisto Juho Hamari Ruediger Zarnekow Technical University of School of Information School of Information Technical University of Berlin Sciences, Sciences, Berlin amirqphj@ University of Tampere University of Tampere ruediger.zarnekow@ mailbox.tu-berlin.de [email protected] [email protected] ikm.tu-berlin.de One of the most prominent fields where Abstract gamification and other gameful approaches have been Physical activity is very important to public health implemented is the health and exercise field [7], [3]. and exergames represent one potential way to enact it. Digital games and gameful systems for exercise, The promotion of physical activity through commonly shortened as exergames, have been gamification and enhanced anticipated affect also developed extensively during the past few decades [8]. holds promise to aid in exercise adherence beyond However, due to the technological advancements more traditional educational and social cognitive allowing for more widespread and affordable use of approaches. This paper reviews empirical studies on various sensor technologies, the exergaming field has gamified systems and serious games for exercising. In been proliferating in recent years. As the ultimate goal order to gain a better understanding of these systems, of implementing the game elements to any non- this review examines the types and aims (e.g. entertainment context is most often to induce controlling body weight, enjoying indoor jogging…) of motivation towards the given behavior, similarly the the corresponding studies as well as their goal of the exergaming approaches is supporting the psychological and physical outcomes. -

Vpliv Gibalnih Sposobnosti Na Žongliranje Diplomsko Delo

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA ŠPORT Športna vzgoja Vpliv gibalnih sposobnosti na žongliranje Diplomsko delo MENTOR: prof. dr. Ivan Čuk SOMENTORICA: doc. dr. Maja Bučar Pajek RECEZENTKA: prof. dr. Maja Pori AVTOR: Blaž Slanič Ljubljana, 2015 ZAHVALA Zahvaljujem se vsem žonglerjem, brez njih diplomskega dela ne bi mogel izpeljati. Zahvala gre tudi mentorju, profesorju dr. Ivanu Čuku, ki mi je pomagal pri sami izvedbi diplomskega dela. Hvala partnerki in staršem, ki me pri mojih žonglersko-akrobatskih podvigih podpirate in mi stojite ob strani. HVALA. Ključne besede: žongliranje, gibalne sposobnosti, učinkovitost Vpliv gibalnih sposobnosti na žongliranje IZVLEČEK: Ker je žongliranje v Sloveniji zelo malo poznano, smo naredili raziskavo o vplivu gibalnih sposobnosti na unčikovitost v žongliranju. V raziskavi smo testirali gibalne sposobnosti slovenskih žonglerjev vseh starosti. Raziskava je vsebovala teste hitrosti, moči, ravnotežja, preciznosti, reakcijskega časa in ritma. Vse teste smo izvedli z levo in desno roko. Pogoj za sodelovanje na raziskavi je bil, da posameznik zna žonglirati s petimi žonglerskimi žogicami. Sodelovalo nas je 16 žonglerjev, starih med 13 in 40 let, in sicer 15 moških in 1 ženska. Na podlagi rezultatov smo ugotavljali, katere od gibalnih sposobnosti so tiste ključne, ki pripomorejo k lažjemu in bolj kontroliranemu žonglerskemu udejstvovanju. Podatki so bili obdelani v programu Excel 2010 in SPSS 16.0. Iz naših rezultatov je razvidno, da imata na učinkovitost v žongliranju največji vpliv bobnanje leva roka (ritem in tempo leve roke) in starost posameznika. Keywords: Juggling, motor skills, efficiency Effects of motor skills on juggling Because of the lesser known nature of jugging in Slovenia, we made our research on the effects of motor skills on it.