Social Innovation and Why It Has Policy Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Citizen Engagement in the Process of Social Innovation

Mapping citizen engagement in the process of social innovation 24 September 2012 Deliverable 5.1 of the FP7-project: TEPSIE (290771) Acknowledgements We would like to thank all of our partners in the TEPSIE consortium for their comments on this paper, and particularly their suggestions of relevant examples of citizen engagement. Suggested citation Davies, A, Simon, J, Patrick, R and Norman, W. (2012) ‘Mapping citizen engagement in the process of social innovation’. A deliverable of the project: “The theoretical, empirical and policy foundations for building social innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE), European Commission – 7th Framework Programme, Brussels: European Commission, DG Research TEPSIE TEPSIE is a research project funded under the European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme and is an acronym for “The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe”. The project is a research collaboration between six European institutions led by the Danish Technological Institute and the Young Foundation and runs from 2012-2015. Date: 24 September 2012 TEPSIE deliverable no: 5.1 Authors: Anna Davies, Julie Simon, Robert Patrick and Will Norman Lead partner: The Young Foundation Participating partners: Danish Technological Institute, University of Heidelberg, Atlantis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Wroclaw Research Centre EIT+ Contact person: Julie Simon The Young Foundation [email protected] +44 8980 6263 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation

TemaNord 2015:562 TemaNord TemaNord 2015:562 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Social entrepreneurship and social innovation Social entrepreneurship and social innovation Initiatives to promote social entrepreneurship and social innovation in the Nordic countries The Nordic countries are currently facing major challenges with regard to maintaining and further developing social welfare. Against this background, the Nordic Council of Ministers decided in autumn 2013 to appoint a working group to map initiatives to support social entrepreneurship and social innovation in the Nordic countries. The main purpose of this mapping is to increase knowledge of initiatives to support social entrepreneurship and social innovation in the Nordic Region in the work to include disadvantaged groups in employment and society. This report presents the results from the mapping and the working group’s recommendations for further follow-up. TemaNord 2015:562 ISBN 978-92-893-4293-3 (PRINT) ISBN 978-92-893-4295-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-92-893-4294-0 (EPUB) ISSN 0908-6692 TN2015562 omslag.indd 1 19-08-2015 12:18:53 Social entrepreneurship and social innovation Initiatives to promote social entrepreneurship and social innovation in the Nordic countries TemaNord 2015:562 Social entrepreneurship and social innovation Initiatives to promote social entrepreneurship and social innovation in the Nordic countries ISBN 978-92-893-4293-3 (PRINT) ISBN 978-92-893-4295-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-92-893-4294-0 (EPUB) http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2015-562 TemaNord 2015:562 ISSN 0908-6692 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2015 Layout: Hanne Lebech Cover photo: ImageSelect Print: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk Printed in Denmark This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

Social Innovation in Cities: State of The

urbact ii capitalisation, december 2014 URBACT is a European exchange and learning programme promoting integrated sustainable urban development. state of the art It enables cities to work together to develop solutions to major urban challenges, re-a�firming the key role they play in facing increasingly complex societal changes. Social innovation URBACT helps cities to develop pragmatic solutions that are new and sustainable, and that integrate economic, social and environmental dimensions. It enables cities to share good practices and lessons learned with all professionals involved in urban in cities policy throughout Europe. URBACT II comprises 550 di�ferent sized cities and their Local Support Groups, 61 projects, 29 countries, and 7,000 active local stakeholders. URBACT is jointly financed by the ERDF and the Member States. Social innovation in cities , URBACT II capitalisation urbact ii urbact , April 2015 www.urbact.eu URBACT Secretariat 5, rue Pleyel 93283 Saint Denis cedex France State of the Art on Social innovation in cities, URBACT II Capitalisation, December 2014 Published by URBACT 5, Rue Pleyel, 93283 Saint Denis, France http://urbact.eu Authors Marcelline Bonneau and François Jégou Graphic design and layout Christos Tsoleridis (Oxhouse design studio), Thessaloniki, Greece ©2015 URBACT II programme urbact ii capitalisation, december 2014 state of the art Social innovation in cities How to deal with new economic and social challenges in a context of diminishing public resources? State of the art of new leadership models and -

Asia Social Innovation Award 2020 Winners Early-Growth Stage Health Impact Award

Asia Social Innovation Award 2020 Winners Early-Growth Stage Grand Prize (HK$100,000, sponsored by CVC Capital Partners) Recognizing a startup demonstrating excellent innovation in creating social impact with commercial potential and scalability. Kanpur Flowercycling Private Limited India | Founded in 2017 | https://phool.co/ ‘Kanpur Flowercycling Private Limited’ is a Kanpur (India) based award-winning social enterprise that has pioneered the world’s first technology to convert temple- flowers and agricultural-stubble waste into innovative and sustainable products, along the way providing livelihood to 79 marginalized women, empowering our mission of preserving the Ganges from pollution. They started with making Incense sticks, cones and Vermicompost, and today are the fastest selling incense brand in India with 13 unique fragrances. With innovation at the heart of the organization, repurposed-flowers and stubble-residues are used to develop biodegradable alternates to Earth’s 5th biggest pollutant i.e. Styrofoam– Florafoam and world’s first vegan leather made from temple flowers– Fleather. Heralded by Fast Company as a World Changing Idea in 2018, recognized by the United Nations in its Young Leaders publishing, and mentioned by Forbes, Fortunes and Stanford Social- Review, KFPL is revolutionizing the way India handles the megaton temple waste and agro-stubble residue problem. Health Impact Award (HK$50,000, sponsored by Johnson & Johnson) Recognizing a startup in the ‘Health & Wellness’ category that seeks to provide better access to care in communities while promoting a culture of health and well-being. Project Asbah India | Founded in 2016 | www.asbah.org.in Project Asbah: Every Drop, A Promise, aims at providing clean drinking water to underprivileged communities and rural households at highly affordable rates. -

Understanding Social Innovation As an Innovation Process

TNO report Understanding Social Innovation as an Innovation Process Research carried out during the EU-FP7 Project “SI- Drive, Social innovation: Driving force of social change”, 2014-2017 August 2018 Understanding Social Innovation as an Innovation Process Research carried out during the EU-FP7 Project “SI-Drive, Social innovation: Driving force of social change”, 2014-2017 Date August 2018 Authors P.R.A. Oeij W. van der Torre S. Vaas S. Dhondt Project number 051.02857 Report number R18049 Contact TNO Peter Oeij Phone +31 6 22 20 52 99 Email [email protected] Acknowledgement: This report is an improvement of an earlier presentation entitled ‘Contemporary Practices of Social Innovation: Collective Action for Collaboration’ at ISA2018, XIX ISA World Congress of Sociology (July 15-21, 2018). Healthy Living Schipholweg 77-89 2316 ZL LEIDEN P.O. Box 3005 2301 DA LEIDEN The Netherlands www.tno.nl T +31 88 866 61 00 [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced and/or published by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without the previous written consent of TNO. In case this report was drafted on instructions, the rights and obligations of contracting parties are subject to either the General Terms and Conditions for commissions to TNO, or the relevant agreement concluded between the contracting parties. Submitting the report for inspection to parties who have a direct interest is permitted. © 2018 TNO Chamber of Commerce number 27376655 Abstract A large-scale international project ‘SI DRIVE: Social innovation, driving force of social change 2014-2017” collected 1,005 cases of social innovation across the globe in seven policy fields: Education, Employment, Energy, Transport , Poverty, Health and Environment (Howaldt et al., 2016). -

Social Value Creation and Social Innovation by Human Service Professionals: Evidence from Missouri, USA

administrative sciences Article Social Value Creation and Social Innovation by Human Service Professionals: Evidence from Missouri, USA Monica Nandan 1,*, Archana Singh 2 and Gokul Mandayam 3 1 Social Work and Human Services, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144, USA 2 Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai 400088, India; [email protected] 3 School of Social Work, Rhode Island College, Providence, RI 02908, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 June 2019; Accepted: 29 October 2019; Published: 8 November 2019 Abstract: Owing to the contextual challenges, human service professionals (HSP) are creating social value (SV) for diverse vulnerable population groups through social innovation. This qualitative exploratory study investigates the nature of SV created by 14 HSPs, representing a diverse range of human service organizations (HSOs), and examines ‘why’ and ‘how’ they innovate. In addition, the study examines HSPs’ current understanding and practices related to social entrepreneurship (SE). The study findings highlight that increased accountability and new funding opportunities challenged HSPs to innovate. HSPs created SV by addressing new unmet needs, developing new collaborations, and employing alternative marketing strategies, thereby ensuring the financial sustainability of their programs and organizations, and promoting social and economic justice. Different understandings of SE were voiced based on the educational backgrounds of HSPs. Without formal training in SE, HSPs trained in social work appeared to use various components of the SE process, though in a haphazard fashion compared to those with a non-social work academic training. We suggest that the graduate curriculum across various disciplines should formally include principles and behaviors related to social innovation and entrepreneurship. -

Social Innovation in Australia: Policy and Practice Developments

SOCIAL INNOVATION AROUND THE WORLD SOCIAL INNOVATION IN AUSTRALIA: POLICY AND PRACTICE DEVELOPMENTS Although it has experienced recent improvements, Australia has historically lagged behind many OECD countries and several of its regional neighbours in its commercial innovation performance. While there is a considerable social innovation activity in Australia, it is not well-enabled by policy frameworks, and is often not documented or evaluated. Jo Barraket There are an estimated 20,000 social enterprises in Australia, INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND operating in every industry of the Australian economy [2]. With a history of cooperative economics since European Contemporary approaches to social innovation in Australia settlement, and a demonstrably enterprising not for profit have to date focused largely on social enterprise sector, there is well-established practice in Australia in using development, new approaches to social finance and social the market to progress social goals. Social enterprise activity procurement as well as citizen-centred social service reforms. in Australia has gone through various waves informed by socio-historic developments such as the rise of new social With its federated political system involving national, state movements, global economic restructuring, technological and local levels of government, Australian policy support for advances, and the march of neoliberalism [3]. Early adopters social innovation has been patchy, while regulatory of neoliberal policy regimes, successive Australian conditions continue to trail emerging practice. The absence governments have supported quasi-market developments in of an explicit commitment to social innovation was a notable areas such as employment services and, more recently, feature of the Commonwealth Government’s innovation services for people with disabilities. -

Unlocking Resilience Through Autonomous Innovation

Working Paper Unlocking resilience through autonomous innovation Aditya Bahadur and Julian Doczi January 2016 Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter © Overseas Development Institute 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Working Papers for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. ISSN (online): 1759-2917 ISSN (print): 1759-2909 Cover photo: During daylight hours a single bottle like this could provide 40-60 watts of light in a dark room. Photo: Jay Directo, AFP, Getty Images, 2011. Contents List of acronyms 5 Executive summary 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Innovation and Autonomous Innovation 7 3. Resilience thinking 14 4. Unlocking resilience through Autonomous Innovation 16 5. Implications for development organisations 21 6. Conclusions 24 References 26 Unlocking resilience through autonomous innovation 3 List of figures and boxes Figures Figure 1: Relationships between different approaches to innovation, according to their degree of external influence and their -

Department of Surgery Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan 0

Department of Surgery Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan 0 Organized by: Department of Surgery Collaborating Departments: Critical Creative Innovative Thinking (CCIT) Department of Anaesthesiology Department of Community Health Sciences Department of Emergency Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology School of Nursing & Midwifery (SONAM) Information: Department of Surgery Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan Tel: +92 21 3486 4374 / 3486 4759 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 Syed Ather Enam Chair, Department of Surgery Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan I welcome all the national and international participants to the 4th AKU Annual Surgical Conference of the Aga Khan University, Karachi. The AKU Annual Surgical Conferences has indeed provided the Aga Khan University, particularly the Department of Surgery, a platform to maintain its reputation as regional academic leaders. We have been able to build upon last year’s conference both in terms of the scale, and the scope. This year’s theme and scientific program on ‘Global Surgery’ is an integral part of Global Health. Although the history of Global Health goes back to the post-world war II era, Global Surgery remained somewhat a neglected segment of the UN and WHO’s efforts in public health initiatives. It has only been in this decade that Global Surgery has started gaining attention. The main reason for this focus grew as the non-communicable diseases became more prominent: when the burden of surgical diseases and a lack of appropriate treatment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries became quite evident. The assumed cost associated with the treatment of surgical problems kept the leaders of the Global Health shying away from this aspect of Public Health. -

Social Innovation What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated

SKOLL CENTRE FOR SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP WORKING PAPER SOCIAL INNOVATION WHAT IT IS, WHY IT MATTERS AND HOW IT CAN BE ACCELERATED GEOFF MULGAN WITH SIMON TUCKER, RUSHANARA ALI AND BEN SANDERS SOCIAL INNOVATION: WHAT IT IS, WHY IT MATTERS AND HOW IT CAN BE ACCELERATED GEOFF MULGAN CONTENTS 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 27-32 STAGES OF INNOVATION 27 SOCIAL ORGANISATIONS AND ENTERPRISES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABOUT THE AUTHORS 28 SOCIAL MOVEMENTS This report is an updated version of a report This paper has been written by Geoff Mulgan with 3 AUTHORS 28 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT published with support from the British Council in input from Young Foundation colleagues Simon 31 MARKETS Beijing in 006. We are grateful to the very many Tucker, Rushanara Ali and Ben Sanders. 31 ACADEMIA individuals and organisations who have shared their 4-6 SUMMARY 31 PHILANTHROPY thoughts and experiences on earlier drafts, including The Young Foundation 32 SOCIAL SOFTWARE AND OPEN SOURCE METHODS in our conferences in China in October 006, as 17-18 Victoria Park Square well as discussion groups that were held in: London, Bethnal Green 7 SOCIAL INNOVATION: AN INTRODUCTION Edinburgh, Oxford, Dublin, Shanghai, Guangzhou, London E2 9PF 7 THE GROWING IMPORTANCE OF SOCIAL INNOVATION 33-35 COMMON PATTERNS OF SUCCESS AND FAILURE Chongqing, Hong Kong, Singapore, Seoul, +44 (0) 0 8980 66 7 THE YOUNG FOUNDATION: A CENTRE OF PAST 34 HANDLING INNOVATION IN PUBLIC CONTEXTS Melbourne, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Amsterdam youngfoundation.org AND FUTURE SOCIAL INNOVATION 34 A ‘CONNECTED DIFFERENCE’ THEORY OF and Bangalore. We are also particularly grateful to SOCIAL INNOVATION the many organisations around the world who are Printed by The Basingstoke Press contributing their ideas and practical experience ISBN 1-905551-0-7 / 978-1-905551-0- 8-12 WHAT SOCIAL INNOVATION IS to the creation of the Social Innovation Exchange First published in 007 8 DEFINING SOCIAL INNOVATION 36-39 WHAT NEXT: AN AGENDA FOR ACTION (socialinnovationexchange.org). -

Government and Social Innovation: Current State and Local Models Andrew Wolk and Colleen Gross Ebinger

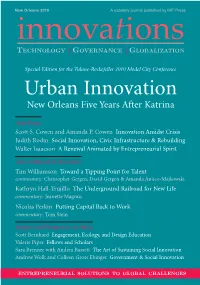

New Orleans 2010 A quarterly journal published by MIT Press innovations TECHNOLOGY | GOVERNANCE | GLOBALIZATION Special Edition for the Tulane-Rockefeller 2010 Model City Conference Urban Innovation New Orleans Five Years After Katrina Lead Essays Scott S. Cowen and Amanda P. Cowen Innovation Amidst Crisis Judith Rodin Social Innovation, Civic Infrastructure & Rebuilding Walter Isaacson A Renewal Animated by Entrepreneurial Spirit Cases Authored by Innovators Tim Williamson Toward a Tipping Point for Talent commentary: Christopher Gergen, David Gergen & Amanda Antico-Majkowski Kathryn Hall-Trujillo The Underground Railroad for New Life commentary: Jeanette Magnus Nicolas Perkin Putting Capital Back to Work commentary: Tom Stein Analysis and Perspectives on Policy Scott Bernhard Engagement, Ecology, and Design Education Valerie Piper Fellows and Scholars Sara Brenner with Andrea Bassett The Art of Sustaining Social Innovation Andrew Wolk and Colleen Gross Ebinger Government & Social Innovation ENTREPRENEURIAL SOLUTIONS TO GLOBAL CHALLENGES innovations TECHNOLOGY | GOVERNANCE | GLOBALIZATION Lead Essays 3 Innovation Amidst Crisis: Tulane University’s Strategic Transformation Scott S. Cowen and Amanda P. Cowen 13 Social Innovation, Civic Infrastructure, and Rebuilding New Orleans from the Inside Out Judith Rodin 21 A City’s Renewal Animated by Entrepreneurial Spirit Walter Isaacson Cases Authored by Innovators The Idea Village 25 Toward a Tipping Point for Talent: How the Idea Village is Creating an Entrepreneurial Movement in New Orleans -

Investing in Social Innovation

Investing in Social Innovation Harnessing the Potential of Partnership Between Corporations and Social Entrepreneurs Jane Nelson Senior Fellow and Director, CSR Initiative John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Beth Jenkins Senior Consultant Booz Allen Hamilton March 2006 ⎪ Working Paper No. 20 A Working Paper of the: Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative A Cooperative Project among: The Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government The Center for Public Leadership The Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations The Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Citation This paper may be cited as: Nelson, Jane and Beth Jenkins. 2006. “Investing in Social Innovation: Harnessing the Potential of Partnership between Corporations and Social Entrepreneurs.” Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper No. 20. Cambridge, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Comments may be directed to the authors. This paper was included as a book chapter in: Perrini, Francesco (Editor). 2006. The New Social Entrepreneurship: What Awaits Social Entrepreneurial Ventures? Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative The Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government is a multi-disciplinary and multi-stakeholder program that seeks to study and enhance the public contributions of private enterprise. It explores the intersection of corporate responsibility, corporate governance and strategy, public policy, and the media. It bridges theory and practice, builds leadership skills, and supports constructive dialogue and collaboration among different sectors. It was founded in 2004 with the support of Walter H. Shorenstein, Chevron Corporation, The Coca-Cola Company, and General Motors. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not imply endorsement by the Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, the John F.