Exhibition Guide Haptic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Leonardo Drew

New York’s best public art installations this season Get outside to check out some of the best art in New York City this fall By Ameena Walker and Valeria Ricciulli Updated Sep 5, 2019, 11:56am EDT Fall is almost here, and with that comes the arrival of dozens of new temporary public art installations, which enliven the urban landscape with abstract pieces, selfie-worthy moments, and more. Here, we’ve collected more than a dozen worth scouting in the next few months; as more cool projects come to light, we’ll update the map—and as always, if you know of anything that we may have missed, let us know in the comments. 1. Carmen Herrera: “Estructuras Monumentales” Broadway & Chambers St New York, NY 10007 (212) 639-9675 Visit Website In City Hall Park, Cuban-born artist Carmen Herrera presents “Estructuras Monumentales,” a set of large-scale monochromatic sculptures that “create a distinctive and iconic clarity by emphasizing what she sees as ‘the beauty of the straight line,’” according to the installation description. Curated by the Public Art Fund, the installation will be on view until November 8, 2019. OPEN IN GOOGLE MAPS 2. Leonardo Drew: “City in the Grass” 11 Madison Ave New York, NY 10010 (212) 520-7600 Visit Website On view in Madison Square Park until December 15, “City in the Grass” by Leonardo Drew is a more than 100-foot-long installation featuring a view of an abstract cityscape on top of a patterned surface that resembles Persian carpet design. The installation invites visitor to walk on its surface and brings together “domestic and urban motifs” that reflect the artist’s interest in global design and East Asian decorative traditions, the description says. -

LEONARDO DREW Born in Tallahassee

LEONARDO DREW Born in Tallahassee, Florida, 1961; lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 1985 BFA, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York, NY 1981-82 Parsons School of Design, New York, NY Solo Exhibitions 2017 Leonardo Drew, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX Number 197, de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA CAM Raleigh, Raleigh, NC Recent Acquistion: Leonardo Drew, Academy Art Museum, Easton, MD 2016 Leonardo Drew, Sikkema Jenkins, New York, NY Leonardo Drew: Eleven Etchings, Crown Point Press, San Francisco, CA 2015 Leonardo Drew, Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong, China Unsuspected Possibilities, SITE Santa Fe, NM Leonardo Drew, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX Leonardo Drew, Pace Prints, New York, NY Leonardo Drew, Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki, Finland Leonardo Drew, Vigo, London, UK 2014 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA 2013 Selected Works, SCAD Museum of Art at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA Exhumation/Small Works, Canzani Center Gallery at Columbus College of Art & Design, Columbus, OH VIGO, London, UK 2012 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY Pace Prints, New York, NY 2011 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA VIGO, London, UK Galleria Napolinobilissima, Naples, Italy 2010 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY Window Works: Leonardo Drew, Artpace, San Antonio, TX 2009 Existed: Leonardo Drew, Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston, TX Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, MA Fine Art Society, London, UK 2007 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY 2006 Palazzo Delle Papesse, Centro Arte Contemporanea, Siena, Italy 2005 Brent Sikkema, New York, NY 2002 The Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia, PA 2001 Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin, Ireland 2000 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY 1999 Madison Art Center, Madison, WI 1998 Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY 1997 Samuel P. -

1 the North Carolina Museum of Art Announces 2020–21 Exhibition

IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 17, 2020 MEDIA CONTACT Kat Harding | (919) 664-6795 [email protected] The North Carolina Museum of Art Announces 2020–21 Exhibition Schedule Featuring North Carolina Painters, Senegalese Jewelry, Leonardo Drew, and Golden Mummies of Egypt Art Museum Debut Raleigh, N.C.—The North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) announces upcoming exhibitions for 2020 through 2021 featuring North Carolina-based painters, site-specific installations, and Golden Mummies of Egypt from the Manchester Museum. This spring, five exhibitions featuring local, national, and global artists will open on the Museum’s ticketed exhibition floor in two phases. • Opening March 7 are Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting and Christopher Holt: Contemporary Frescoes/Faith and Community, a behind-the-scenes look at Asheville-based fresco artist Christopher Holt, paired with Art in Translation featuring works by Thai artist Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook. • Starting April 7, these exhibitions will be joined by Good as Gold: Fashioning Senegalese Women and an indoor-outdoor exhibition by New York-based artist Leonardo Drew. Fall 2020 will feature Golden Mummies of Egypt with eight extraordinary mummies from the Manchester Museum collection. The exhibition at the NCMA is its debut at an art museum, following a stint at the Buffalo Museum of Science in New York. Full schedule and descriptions are below. Spring 2020 Exhibitions Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting March 7–July 26, 2020 East Building, Level B, Joyce W. Pope Gallery Throughout modern art history, painting has been declared dead and later resuscitated so many times that the issue now tends to fall on deaf ears. -

Leonardo Drew Commissioned to Create New Public Art Project at Madison Square Park

LEONARDO DREW COMMISSIONED TO CREATE NEW PUBLIC ART PROJECT AT MADISON SQUARE PARK City in the Grass envisions a conceptual city within the Park, where visitors can engage directly with its structures and surfaces On view from June 3 through December 15, 2019 Installation in-process for City in the Grass, commissioned by Madison Square Park Conservancy. Photographer credit: Hunter Canning. New York, NY | May 31, 2019—Madison Square Park Conservancy has commissioned Leonardo Drew to create a monumental new public art project for the Park opening this spring. Marking the Conservancy’s 38th commissioned exhibition and the artist’s most ambitious work to date, City in the Grass presents a topographical view of an abstract cityscape atop a patterned panorama. Building on the artist’s signature techniques of assemblage and additive collage, the installation extends over 100 feet long with a richly textured surface that invites visitor engagement. City in the Grass is on view from June 3, 2019, through December 15, 2019. “In this teeming urban space, Leonardo Drew's goal has been to bring people close in to his work, to study the swells and folds of his cityscape, and to locate a personal place within the purposeful voids in the work,” said Brooke Kamin Rapaport, exhibition curator and Deputy Director and Martin Friedman Senior Curator of Madison Square Park Conservancy. “This is a symbolic and literal multilayered project. The artist builds layer on layer of materials while using the metaphor of a torn carpet as a complicated reference to home, comfort, and sanctuary. Viewers can look onto City in the Grass as if they are giants assessing a terrain; upon sitting along the Oval Lawn's green expanse, they are able to embed themselves within the fabric of the sculpture.” For City in the Grass, Drew has crafted a sprawling work of varied materials that undulates across the lawn and, at various points, crescendo into towers rising up to 16 feet tall. -

Leonardo Drew: Works on Paper 26 August Through 1 October 2021

Leonardo Drew: Works on Paper 26 August through 1 October 2021 Anthony Meier Fine Arts is pleased to present an exhibition of new works on paper, the gallery’s fourth solo exhibition with Brooklyn-based artist Leonardo Drew. Known for his abstract sculptural works, Leonardo Drew creates artworks that expand and explode into the space they occupy. Typically working in large scale with raw materials including wood, cotton and scrap metal – all carrying references to America’s past – Drew transforms chaos into balanced order while addressing social and historical topics. In this suite of works on paper, Drew employs a similar aesthetic on a smaller scale. Collaged sculptures of plaster bits, paint chunks, cast paper and bundled straw fit neatly into a square frame. The intentional scale and finite border lend order from the outside in, a clear juxtaposition to the familiar expression within. Leonardo Drew was born in 1961 in Tallahassee, Florida. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. His works have been shown internationally and are held in numerous public collections including the deYoung Museum, San Francisco; San Francisco International Airport; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; and Tate, London. Recent solo museum exhibitions include Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC; Madison Square Park, New York; SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah (2013); the Columbus College of Art & Design (2013); Palazzo Delle Papesse, Centro Arte Contemporanea, Siena, Italy (2006); and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. -

WINTER Exhibitions and Programs January 26–June 3, 2020

WINTER Exhibitions and Programs January 26–June 3, 2020 The Museum is free for all UC Davis | manettishrem.org | 530-752-8500 Calendar at a Glance January March April Continued 28 Creative Writing 26 Winter Season 4 Faculty Book Series: Reading Series: Celebration, Mark C. Jerng, Public Executions, 3–5 PM 4:30–6 PM 4:30–6 PM 11 The China Shop: 30 Visiting Artist Lecture: February Artists in Science Meg Shiffler, Labs, 4:30–6 PM 4:30–6 PM 5 Faculty Book Series: 12 Visiting Artist Lecture: Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli, 30 Artist Salon, Artist Francis Stark, 4:30–6 PM Tour 2.0 4:30–6 PM 7–8:30 PM 6 Thiebaud Endowed Photo: Meagan Lucy 26 Artist Salon, King Lecture: Leonardo Effect: Aerial Views, Drew, 4:30–6 PM Vantage Points and May 6 Artist Salon, Evolving Perspectives 6 The Scholar as Curator Decisions, Decisions: 7–8:30 PM Join us for a festive Series: Roger Sansi, Questions in the 4:30–6 PM Practice Winter Season Celebration 7–8:30 PM April 28 Graduate Exhibition Opening Celebration, 13 Davis Human Rights 2 Visiting Artist Lecture: 6–9 PM Lecture: Gilda Beatriz Cortez, Sunday, January 26, 3–5 PM Gonzales, 4:30–6 PM 30 Annual Art History 7–8:30 PM Graduate Colloquium, 18 Picnic Day, 1–4 PM First-generation UC Davis artists are featured in two compelling new exhibitions 23 Robert Arneson’s 11 AM–5 PM “Black Pictures”: opening at this event: Stephen Kaltenbach: The Beginning and The End and 26 Museum Talk, The Gwendolyn DuBois Gesture: The Human Figure After Abstraction | Selections from the Manetti Architecture of the June Shaw, 2:30 PM Shrem Museum. -

Leonardo Drew

Issue 6 // Free Leonardo Drew Leonardo Drew • Cameron Platter • Jordan Casteel • Jibade-Kahalil Huffman • ruby onyinyechi amanze • Cataloging Community Part Four • Millennial Collectors: Nicolas Hugo • Mark Flood • 8 Ball • Leo Fitzpatrick + FTL Leo Fitzpatrick + FTL | NYAQ 2016 ABHK17_Ads_GenericAd_11x21.indd 1 05.10.16 18:17 My first question is borrowed from one of my favorite you as you transfer your lived experience as material instructors who would always begin class this way. back. That actually brings me to another question I Leonardo Drew She would ask us all what our current obsession is, or had, which was about cannibalism. something that’s kind of been on your mind or in your In Conversation With body within the last week or so. So I want to ask you I was watching your interview for the Against the what your current obsession is. Grain show and you mention that term, and at first Tasha Ceyan My current obsession is color; I’ve been obsessing over this there seemed to be a kind of—resistance to it, but for the last year, maybe longer than that. I thought that I would then I read another interview in the Wall Street Jour- have resolved it by now, but it has been perplexing and ongo- nal where you talk about curator Valerie Cassel Oli- ing. This is an interesting segue into a number of issues I would ver’s use of “material cannibalism” and how you feel As we discuss in the interview, I’ve never seen Leonardo Drew’s to address. Because honestly, by route, you can create work, a resonance with it. -

1968 Exhibitions (At the A. D. White House)

Exhibitions at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University 1 1968 Exhibitions (at the A. D. White House) Irish Architectural Drawings A Medieval Treasury January 2–January 31 October 8–November 3 Contemporary American Drawings Andre Smith: Paintings, Drawings, and Prints January 13–February 4 October 14–November 10 Twentieth-Century Art: The European Heritage Recent Sculpture by Jack Squier February 6–February 25 November 12–December 8 The Artist and His Subject Prints for Purchase February 9–March 3 November 19–December 15 Radius 5 Goya: The Disasters of War February 10–February 25 December 20, 1968–February 12, 1969 Young Artists of Africa February 27–March 17 The Academic Ideal February 29–March 21 Views of Tokaido March 21–April 7 Additional Views of the Tokaido– Twelve Hiroshige Prints March 21–April 7 Whitney Museum: Selection I April 3–May 12 American Still Life Painting July 12–August 2 George Grosz: Watercolors and Drawings July 16–August 4 Lyonel Feininger: The Ruin By the Sea August 6–August 25 Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century European Drawings August 13–September 29 Dutch and Flemish Prints from the Seventeenth Century September 3–September 29 Max Ernst: Works on Paper September 9–September 29 Tony Smith: Sculpture September 9–September 29 Exhibitions at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University 2 1969 Exhibitions (at the A. D. White House) Paul Feeley: Watercolors and Drawings Prints for Purchase January 4–February 2 November 13–December 14 Earth Art Jacques Callot. The Misfortunes of War February -

Leonardo-Drew-E-Catalogue.Pdf

Leonardo Drew was born in 1961 in Tallahassee, Florida, and he grew Leonardo Drew’s work has been exhibited across the USA and up in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Drew seemed bound to work as a internationally. Major solo exhibitions include Vigo Gallery, London, professional artist from a young age; his works were exhibited publically UK (2015); Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA, USA (2014); for the first time when he was only 13 years old. By the age of 15 he was Selected Works, SCAD Museum of Art at the Savannah College of Art being courted by both DC and Marvel Comics to work as an illustrator. and Design, Savannah, GA, USA (2013); Existed: Leonardo Drew, Blaffer However, Drew would apply his talents to a very different artistic path. Gallery, Art Museum of the University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA He became inspired by abstract works, especially those of Jackson (2009); Palazzo Delle Papesse, Centro Arte Contemporanea, Siena, Pollock and Piet Mondrian. Drew went on to attend the Parsons School Italy (2006); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian of Design in New York, and he earned a BFA from Cooper Union in 1985. Institution, Washington, DC, USA (2000); The Bronx Museum of the Drew’s works are always sculptural, although he tends to avoid making Arts, Bronx, NY, USA (2000); and Museum of Contemporary Art, San freestanding pieces. Instead, he will often mount objects onto panels Diego, CA, USA (1995). or directly to the wall, which can be seen as a nod to his beginnings as Recent major group exhibitions include Unsuspected Possibilities, a painter and draftsman. -

Leonardo Drew

LEONARDO DREW 1961 Born in Tallahassee, FL, USA Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, NY, USA EDUCATION 1985 BFA, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York 1981–82 Parsons The New School for design, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, USA Eleven Etchings, Crown Point Press, San Francisco, CA, USA 2015 Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong Unsuspected Possibilities, SITE, Santa Fe, NM, USA Pace Prints, New York, NY, USA Galerie Forsblom, Helsinki, Finland Vigo, London, UK 2014 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA, USA 2013 SCAD Museum of Art at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA, USA Canzani Center Gallery at Columbus College of Art & Design, Columbus, OH, USA VIGO, London, UK 2012 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, USA Pace Prints, New York, NY, USA 2011 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA, USA VIGO, London, UK Galleria Napolinobilissima, Naples, Italy 2010 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, USA Artpace, San Antonio, TX, USA 2009 Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston, TX, USA; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC, USA 2010; DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, MA, USA 2010 Fine Art Society, London, UK 2007 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, USA 2006 Palazzo Delle Papesse, Centro Arte Contemporanea, Siena, Italy 2005 Brent Sikkema, New York, NY, USA 2002 The Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2001 Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY, USA Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin, Ireland 2000 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY, USA 1999 Madison Art Center, Madison, WI, USA 1998 Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY, USA 1997 Samuel P. -

29Th International Sculpture Conference the Multifaceted Maker

29th International Sculpture Conference The Multifaceted Maker October 12-15, 2019 / Portland, OR Presented by the International Sculpture Center. Partners & Sponsors: Arts Council of Lake Oswego, Art Research Enterprises, Art Work Fine Art Services, Inc., Bullseye Glass Company, Ed Carpenter, Eichinger Sculpture Studio, Form 3D, Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, King School Museum of Contemporary Art, Leland Iron Works, Littman and White Galleries, Michael Curry Design, Mudshark Studios, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Pacific Northwest Sculptors, Portland Art Dealers Association, Portland Art Museum, Portland Community College, Portland Open Studios, Portland State University, Profile Laser LLC, Reed College, Regional Arts & Culture Council, and Savoy Studios. This program is made possible in part by funds from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts and by funds from the National Endowment for the Arts. 29th International Sculpture Conference The Multifaceted Maker October 12-15, 2019 / Portland, OR Presented by the International Sculpture Center. Partners & Sponsors: Arts Council of Lake Oswego, Art Research Enterprises, Art Work Fine Art Services, Inc., Bullseye Glass Company, Ed Carpenter, Eichinger Sculpture Studio, Form 3D, Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, King School Museum of Contemporary Art, Leland Iron Works, Littman and White Galleries, Michael Curry Design, Mudshark Studios, Pacifi c Northwest College of Art, Pacifi c Northwest Sculptors, Portland Art Dealers Association, Portland Art Museum, Portland Community College, Portland Open Studios, Portland State University, Profi le Laser LLC, Reed College, Regional Arts & Culture Council, and Savoy Studios. This program is made possible in part by funds from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts and by funds from the National Endowment for the Arts. -

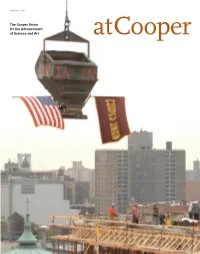

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Atcooper 2 | the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Summer 2008 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art atCooper 2 | The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Message from President George Campbell Jr. Union As the academic year draws to a close, The Cooper Union commu- At Cooper Union Summer 2008 nity can look back over 2007-08 with a profound sense of accom- plishment. At commencement we celebrated four new Fulbright scholars who will pursue their studies in Peru, Tunisia, Japan and Kazakhstan. Since 2001, our graduates have won an astonishing 28 Fulbright scholarships—approximately seven percent of all Fulbright Awards in art, architecture and engineering. Another 149th Commencement 3 National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship was awarded to a Cooper Union graduate this year, bringing the total to 11 since News Briefs 4 2004, making the college also one of the nation’s top producers of New Pledges to Cooper Union NSF Fellowships. Cooper Union’s electrical engineering seniors l e r o S New Trustees swept first, second and third prizes in the student research paper o e Barack Obama Speaks at The Cooper Union L competition sponsored by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Benefactors Join Lifetime Giving Societies Engineers; and our chemical engineering students won first prize In Memoriam: John Jay Iselin in the national Chem-E-Car competition, sponsored by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and designed to stimulate Features 8 research in alternative fuels. Civil engineering students won one of Dynamic Forces: the concrete canoe competitions and took third place overall in the Jesse Reiser (AR’81) and Nanako Umemoto (AR’83) Steel Bridge competition.