Caregiving: Next of Kin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of University Of

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2012 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2012 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM 2012 HOUSTON BASEBALL CREDITS Executive Editor Jamie Zarda Kailee Neumann Allison McClain Editors Dave Reiter, Jeff Conrad Editorial Assistance Mike McGrory Layout Jamie Zarda, Allison McClain Printing University of Houston Printing and Postal Services UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 3100 Cullen Blvd. Houston, Texas 77204-6002 www.UHCougars.com MEDIA ALMANAC INTRODUCTION Career Leaders 68-69 GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents 3 Single-Season Leaders 70-71 Location Houston, Texas Media Information 4 Team Single-Season Leaders 72-73 Enrollment 39,800 Roster 5 Year-by-Year Leaders 74-76 Founded 1927 INTRODUCTION Schedule 6 Year-by-Year Lineups 77-79 Nickname Cougars Against Ranked Teams 80-81 Colors Scarlet and White COACHING STAFF Year-by-Year Pitching Stats 82 President Dr. Renu Khator Todd Whitting 8 Year-by-Year Hitting Stats 83 Athletics Director Mack Rhoades Trip Couch 9 Standout Hitting Performances 84 Faculty Representative Dr. Richard Scamell Jack Cressend 10 Standout Pitching Performances 85 SWA DeJuena Chizer Ryan Shotzberger/Traci Cauley 11 Attendance Records 86 Conference Conference USA Support Staff 12 Coaching History 87 Began C-USA Competition 1996 All-Time Roster 88-89 2012 COUGARS All-Time Jersey Numbers 90-91 BASEBALL STAFF Season Preview 14 The Last Time... 92 Head Coach Todd Whitting Cannon/Lewis 15 Retired Jersey 93 Alma Mater, Year Houston, 1995 Morehouse -

NOKR Information Kit 2005

NOKR Information Kit 2005 WWW.PLEASENOTIFYME.ORG OR WWW.NOKR.ORG INDEX Frequently Asked Questions 3-8 Recent Press Release 9 Where is NOKR Used 10 Strategic Goal Timeline 11 NOKR Current Campaign 12-13 Mission Statement 14 NOKR Staff 15 NOKR Board of Directors 16 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS What is the National Next of Kin Registry? The National Next Of Kin Registry (NOKR) is a new high-speed solution to locating your Next Of Kin in urgent situations. This free service is offered to individuals and to Local and State Agencies internationally. NOKR is a nonprofit organization that was created to assist in the notification process when an individual is missing, injured or deceased. There has been no system or service of this kind in place, until now. The luxury of the Internet is the ability to communicate efficiently across the globe at lightning speed, bringing a nation of people together. NOKR is a front-line approach to accelerate this location and notification process. NOKR is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) public benefit organization. When will our information be used? Here are just a few cases where your information will be useful. Missing or injured child, adult or senior Accidents while traveling nationally or internationally Unconscious person unable to communicate Natural disasters Terrorist acts nationally or internationally Deceased person used to locate a next of kin or point of contact How does NOKR work? You would visit the registration page or the mail-in / fax form page and register either yourself and a point of contact for next of kin or you could register a family member and a point of contact as a next of kin. -

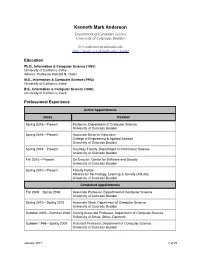

Kenneth Mark Anderson Department of Computer Science University of Colorado, Boulder

Kenneth Mark Anderson Department of Computer Science University of Colorado, Boulder [email protected] http://www.cs.colorado.edu/~kena/ Education Ph.D., Information & Computer Science (1997) University of California, Irvine Advisor: Professor Richard N. Taylor M.S., Information & Computer Science (1992) University of California, Irvine B.S., Information & Computer Science (1990) University of California, Irvine Professional Experience Active Appointments Dates Position Spring 2016—Present Professor, Department of Computer Science University of Colorado Boulder Spring 2016—Present Associate Dean for Education College of Engineering & Applied Science University of Colorado Boulder Spring 2015—Present Courtesy Faculty, Department of Information Science University of Colorado Boulder Fall 2013—Present Co-Director, Center for Software and Society University of Colorado Boulder Spring 2010—Present Faculty Fellow Alliance for Technology, Learning & Society (ATLAS) University of Colorado Boulder Completed Appointments Fall 2005—Spring 2016 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science University of Colorado Boulder Spring 2010—Spring 2013 Associate Chair, Department of Computer Science University of Colorado Boulder Summer 2005—Summer 2006 Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science University of Århus, Århus, Denmark Summer 1998—Spring 2005 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science University of Colorado Boulder January 2017 1! of !21 Research Interests Software Engineering, Software Architecture, Crisis -

Houston Houston

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON 2019 BASEBALL RECORDS BOOK WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM HOUSTON BASEBALL ALL-TIME SERIES RECORDS Total Current First Last Total Current First Last Opponent Games W-L-T Pct. Streak Game Game Opponent Games W-L-T Pct. Streak Game Game Air Force 2 2-0-0 1.000 W2 1971 1971 Northeastern 3 2-1-0 .667 L1 2013 2013 Alabama 18 10-8-0 .555 L1 1976 2016 Northern Illinois 3 1-2-0 .333 L2 1969 1979 Alabama State 3 3-0-0 1.000 W3 2017 2017 Northwestern State 35 25-10-0 .714 L2 1951 2007 Arizona 4 2-2-0 .500 W2 1960 2001 Northwood Institute 1 1-0-0 1.000 W1 1989 1989 Arizona State 15 3-12-0 .200 L7 1967 2010 North Texas 13 13-0-0 1.000 W13 1984 1988 Arkansas 65 27-38-0 .415 L1 1975 2015 Notre Dame 1 1-0-0 1.000 W1 1985 1985 Arkansas State 1 1-0-0 1.000 W1 1979 1979 Ohio State 7 7-0-0 1.000 W7 1952 1999 Auburn 3 1-2-0 .333 L1 1976 1989 Oklahoma 26 7-19-0 .269 L6 1953 2008 Baylor 159 69-90-0 .434 W2 1951 2017 Oklahoma State 87 41-45-1 .466 W2 1951 2012 Boston College 2 1-1-0 .500 W1 1953 1967 Oral Roberts 4 2-2-0 .500 W2 1987 2006 Bradley 5 3-2-0 .600 L2 1951 1959 Pacific 6 2-4-0 .166 L3 2008 2009 Brooke Medical Center 3 0-3-0 .000 L3 1949 1951 Penn State 2 2-0-0 1.000 W2 2013 2013 Bryant 1 1-0-0 1.000 W1 2014 2014 Pepperdine 5 2-3-0 .400 L3 2003 2014 Buffalo 3 3-0-0 1.000 W3 2015 2015 Pershing 5 1-4-0 .200 L4 1968 1968 California 7 5-2-0 .714 L1 1984 2013 Prairie View A&M 13 13-0-0 1.000 W13 1987 2018 Cal Poly 6 4-2-0 .666 W4 2009 2010 Princeton 4 4-0-0 1.000 W4 2000 2007 Cal-Poly Pomona 3 3-0-0 1.000 W3 1988 1988 Purdue 2 2-0-0 1.000 W2 2018 2018 Cal State Fullerton 16 5-11-0 .313 W2 1982 2018 Rice 187 81-106-0 .433 W2 1948 2018 Centenary 3 2-1-0 .667 L1 1981 1984 Rutgers 3 2-1-0 .667 W2 2014 2014 Central Michigan 15 11-4-0 .733 L1 1981 1991 St. -

Download the PDF Version

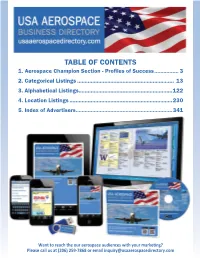

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Aerospace Champion Section - Profiles of Success ................ 3 2. Categorical Listings ................................................................ 13 3. Alphabetical Listings..............................................................122 4. Location Listings ....................................................................230 5. Index of Advertisers................................................................341 Want to reach the our aerospace audiences with your marketing? Please call us at (206) 259-7868 or email [email protected] AEROSPACE CHAMPION SECTION PROFILES OF SUCCESS A&M Precision Measuring Services .......................................... 4 ABW Technologies, Inc. .............................................................. 5 AIM Aerospace, Inc. .................................................................... 6 Air Washington ..........................................................................10 Finishing Consultants ................................................................ 2 General Plastics Manufacturing Company ............................... 7 Greenpoint Technologies ........................................................... 8 Service Steel Aerospace Corp. .................................................. 9 Washington Aerospace Training and Research Center .........11 Click here to see the entire Advertiser Index .......................341 Want to reach the our aerospace audiences with your marketing? Please call us at (206) 259-7868 or email -

Annual Report 2010

2010 Annual Report 2010 Oklahoma City Community Foundation Annual Report | 1 2 | Introduction Our Vision The Oklahoma City Community Foundation values integrity, stewardship and collaboration. We strive to be enlightened leaders with a long-term perspective of community issues and opportunities, and we encourage and assist donors’ philanthropy for the benefit of the community. 2010 Oklahoma City Community Foundation Annual Report | 1 Dear Donors and Friends: The Oklahoma City Community Foundation values integrity, stewardship and collaboration. We strive to be enlightened leaders with a long-term perspective of community issues and opportunities, and we encourage and assist donors’ philanthropy for the benefit of the community. The last task of the 2009 Long Range Plan process was to write a new vision statement for the Oklahoma City Community Foundation. The statement above (and also on page 1) was adopted by the Trustees in February 2010. Throughout this annual report and in additional materials that you receive from us, you will see this theme of leadership with a long-term perspective. The endowment resources that we have been fortunate to develop through the years provide an opportunity to stay with community issues for as long as needed to make a difference. As long-term stewards of donors’ endowment gifts, we work to ensure that the donors’ intent is both respected and relevant. Education at all levels is of major importance in our country and in our state. Through our scholarship programs, counselor training workshops and literacy promotion efforts, we are making a significant contribution to increasing the capacity of individuals to improve themselves and become independent and productive citizens. -

25YEARS of INNOVATION and IMPACT

CELEBRATING • of INNOVATION 25 YEARS and IMPACT 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 ANNUAL REPORT SAVING LIVES, Twenty-five years ago, Partners In Health was founded to support a tiny health clinic serving a destitute squatter settlement in rural Haiti. Today, the community- REVITALIZING COMMUNITIES, based approach used in Cange has helped to transform global health, and Partners In Health continues to provide high-quality health care to poor people in Haiti and TRANSFORMING GLOBAL HEALTH. nine other countries, including the United States. Cover: A community health worker vaccinates a woman in rural Haiti. Above: Pregnant women stay at a mothers’ waiting house to deliver their babies in a clinic with skilled attendants. Photo by Jon Lascher Photo by Charles Howes EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE Dear Friends, In 2012, we celebrated our 25th year In 25 years, we’ve treated millions of patients and proved that at Partners In Health. As we look back complex treatments can be delivered effectively in settings of across the span of a quarter-century, poverty. We’ve developed the infrastructure necessary to deliver Paul Farmer and I are proud of what high-quality care: hospitals and community health facilities and PIH has accomplished in Haiti, Rwanda, the pharmacies, supply chains, and medical technologies to Boston, and beyond, as a beacon of support them. Globally, we’ve insisted that we look more closely what is possible in service to the poor. at the notion of cost, whether for a drug or an intervention, when it We feel lucky to still be doing this work impedes the delivery of lifesaving care. -

Case 20-10166-JTD Doc 844 Filed 07/01/20 Page 1 of 8 Case 20-10166-JTD Doc 844 Filed 07/01/20 Page 2 of 8 EXHIBIT A

Case 20-10166-JTD Doc 844 Filed 07/01/20 Page 1 of 8 Case 20-10166-JTD Doc 844 Filed 07/01/20 Page 2 of 8 EXHIBIT A Case 20-10166-JTD Doc 844 Filed 07/01/20 Page 3 of 8 Lucky's Market Parent Company, LLC, et al. - Service List to e-mail Recipients Served 6/26/2020 ASHBY & GEDDES, PA ASHBY & GEDDES, PA AUSTRIA LEGAL, LLC KATHARINA EARLE WILLIAM P. BOWDEN MATTHEW P. AUSTRIA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BALLARD SPAHR LLP BALLARD SPAHR LLP BALLARD SPAHR LLP CRAIG SOLOMON GANZ DUSTIN P. BRANCH LAUREL ROGLEN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BALLARD SPAHR LLP BALLARD SPAHR LLP BALLARD SPAHR LLP LESLIE HEILMAN MATTHEW G. SUMMERS STACY H. RUBIN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BIELLI & KLAUDER, LLC BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP DAVID M. KLAUDER ANDREW J. ROTH-MOORE STEVEN E. ABELMAN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BUCHALTER, PC BUCHANAN INGERSOLL & ROONEY PC CLARK HILL PLC SHAWN M. CHRISTIANSON MARY CALOWAY KAREN M. GRIVNER [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] COLE SCHOTZ PC COLE SCHOTZ PC DUANE MORRIS LLP J. KATE STICKLES JACOB S. FRUMKIN JARRET P. HITCHINGS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ELLIOTT GREENLEAF, P.C. FAUSONE BOHN, LLP FROST BROWN TODD LLC SHELLEY A KINSELA CHRISTOPHER S. FRESCOLN A.J. WEBB [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FROST BROWN TODD LLC HAHN & HESSEN LLP HAHN & HESSEN LLP RONALD E. -

Registry Helps Track Down Next of Kin

Registry helps track down next of kin By DEIRDRE NEWMAN - Staff Writer NCTimes.net "To say I was devastated is an understatement," said Cerney, 38, a former Marine who lives in Temecula with his wife and three children. Attuned to the plethora of technological options available these days, he wondered why no system existed to notify relatives of people who were either dead or injured, but couldn't speak for themselves. The terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, reinforced his conviction that something was lacking in the ability to notify family when emergency response officials were carrying bodies out of the rubble of the World Trade Center and people didn't know if their relatives were among the dead, he said. Inspired to act, he enlisted his wife to help him in his effort. They originally intended to find someone else who was already working to expedite the contact process so they could help promote the service. But they couldn't find anything remotely like that, he said. So they decided to do it themselves. They created the National Next of Kin Registry, a free service that takes advantage of the Internet to provide peace of mind to the family and friends information for people who are missing, injured or dead. To date, about 4 million people, most in the United States, have registered, he added. While the service is listed on the front page of the California state Web site and is also accessible on FirstGov.gov, the federal government's Web portal, officials with both the California Highway Patrol headquarters in Sacramento and the California State Coroners Association said they hadn't heard of it. -

The Secondary Effects of Helping Others

January 2016 Secondary Effects of Helping Others Bibliography 1 1 The Secondary Effects of Helping Others: A Comprehensive 1 Bibliography of 2,017 Scholarly Publications Using the Terms 1 Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, Secondary 1 Traumatic Stress, Vicarious Traumatization, Vicarious 1 1 Transformation and ProQOL 16 January 2016 ProQOL.org Copyright: This document is public domain material. It may copied, used and shared freely without author permission. Suggested Reference: Stamm, B.H. (2016). The Secondary Effects of Helping Others: A Comprehensive Bibliography of 2,017 Scholarly Publications Using the Terms Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, Secondary Traumatic Stress, Vicarious Traumatization, Vicarious Transformation and ProQOL. http://ProQOL.org. January 2016 Secondary Effects of Helping Others Bibliography 2 Date: 16 January 2016 Compiler: Beth Hudnall Stamm Reference: Stamm, B.H. (2016). The Secondary Effects of Helping Others: A Comprehensive Bibliography of 2,017 Scholarly Publications Using the Terms Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, Secondary Traumatic Stress, Vicarious Traumatization, Vicarious Transformation and ProQOL. http://ProQOL.org. Notes on Using the Bibliography This bibliography is comprehensive but not exhaustive. A general internet database search for professional literature on the topic indicates that there may be as many as several thousand professional documents. It is incumbent on the user to verify the references given and conduct additional research on their particular topic within the general field. Neither the compiler nor the ProQOL make any claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the bibliography. Inclusion Criteria Terms included in Alphabetical Order: compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, vicarious traumatization and ProQOL. Criteria for inclusion in the bibliography: the document must contain as (1) a keyword and/or (2) was verified as occurring within the text of the document at least one of the included terms. -

Taylor White

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2011 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2011 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM 2011 HOUSTON BASEBALL CREDITS Executive Editor Jamie Zarda Editors Cassie Arner, Jeff Conrad Editorial Assistance Mike McGrory, Alissa Bauer, Kailee Gorman Layout Jamie Zarda, Adam Quisenberry Printing University of Houston Printing and Postal Services UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 3100 Cullen Blvd. Houston, Texas 77204-6002 www.UHCougars.com MEDIA ALMANAC INTRODUCTION 2010 IN REVIEW GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents 3 2010 In Review 32 Location Houston, Texas Media Information 4 2010 Overall Stats 33 Enrollment 37,000 Roster 5 2010 Results 34 Founded 1927 INTRODUCTION Schedule 6 2010 Conference USA Stats 35 Nickname Cougars 2010 Home Run Breakdown 36 Colors Scarlet and White COACHING STAFF 2010 Game Highs 37 President Dr. Renu Khator Todd Whitting 8 2010 Standings & Honors 38 Athletics Director Mack Rhoades Trip Couch 9 2010 Conference USA Standings 39-40 Faculty Representative Dr. Richard Scamell Jack Cressend 10 SWA DeJuena Chizer Steven Trout 11 2011 OPPONENTS Conference Conference USA Traci Cauley 11 Opponent Information 42-43 Began C-USA Competition 1996 Support Staff 12 Series History 44-47 Silver Glove Series 48 BASEBALL STAFF 2011 COUGARS Head Coach Todd Whitting Season Preview 14 HISTORY & RECORDS Alma Mater, Year Houston, 1995 Joel Ansley 15 Cougars in the Majors 50 Record at Houston First Season Chase Dempsay 15 MLB Draft Picks 51 Career Record First Season -

Innovation to Transformation 2011 Annual Report Director’S Message

From Innovation To Transformation 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Director’s Message Dear Friends, As 2011 draws to a close, Partners In Health is approaching several major milestones. On January 12, we will observe the second anniversary of the devastating earthquake that destroyed Haiti’s capital and killed over a quarter million people. Six months later, we will celebrate the opening of the 320-bed, national referral and teaching hospital we have been building at breathtaking speed in Mirebalais. Around the same time, we will spend the last of the tens of millions of dollars we received after the earthquake, fulfilling the commitment of our Stand With Haiti plan to invest it all in emergency relief and long-term reconstruction over a 30-month period. On my first visit to Haiti following the earthquake, I observed, “Haiti’s catastrophe will forever divide its history into before earthquake and after.” I also realized, although I didn’t say so at the time, that the earthquake would demarcate PIH’s history as well. In the two years since the earthquake—with the support of so many of you who have rallied to our side—our Haitian colleagues have truly performed miracles. They have worked tirelessly to provide lifesaving medical care to tens of thousands of people affected first by the earthquake and then, less than a year later, by a deadly outbreak of cholera that has now killed more than 6,500 people and sickened nearly half a million. They have reinforced our own services and supported national initiatives to strengthen rehabilitative medicine, mental health, and other specialties that had always been weak in Haiti and were even more desperately needed by a population scarred physically and emotionally by the back-to-back disasters.