2016.11.02 Crisis Management Infopak KD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theranos As a Legal Ethics Case Study

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2021 How and Why Did It Go So Wrong?: Theranos as a Legal Ethics Case Study G. S. Hans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons DATE DOWNLOADED: Mon May 24 12:25:08 2021 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: Bluebook 21st ed. G. S. Hans, How and Why Did It Go So Wrong?: Theranos as a Legal Ethics Case Study, 37 GA. St. U. L. REV. 427 (2021). ALWD 6th ed. Hans, G. G., How and why did it go so wrong?: Theranos as a legal ethics case study, 37(2) Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 427 (2021). APA 7th ed. Hans, G. G. (2021). How and why did it go so wrong?: Theranos as legal ethics case study. Georgia State University Law Review, 37(2), 427-470. Chicago 17th ed. G. S. Hans, "How and Why Did It Go So Wrong?: Theranos as a Legal Ethics Case Study," Georgia State University Law Review 37, no. 2 (Winter 2021): 427-470 McGill Guide 9th ed. G S Hans, "How and Why Did It Go So Wrong?: Theranos as a Legal Ethics Case Study" (2021) 37:2 Ga St U L Rev 427. AGLC 4th ed. G S Hans, 'How and Why Did It Go So Wrong?: Theranos as a Legal Ethics Case Study' (2021) 37(2) Georgia State University Law Review 427. MLA 8th ed. -

Open House Program

Open House Agenda Monday, October 7, 2019 | 8:45 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. | North Gate Hall Twitter: @UCBSOJ | Instagram: @BerkeleyJournalism Hashtags: #UCBSOJ #BerkeleyJournalism Open House is designed for prospective students to attend as many of the day’s sessions as they wish, creating a day that best suits their needs. The expectation is that attendees will come and go from classes and information sessions as needed. Events (See Bios and Descriptions for more info) 8:45 am – 9:00 am Coffee & Refreshments (Courtyard) 10:00 am – 10:30 am Career Planning (Room B1) 10:30 am – 11:00 am Financial Planning (Room B1) 11:30 am – Noon Welcome Address by Dean Wasserman (Library) Noon – 1:00 pm Lunch (Courtyard) We’ll have themed lunch tables which you can join in order to learn more about different reporting areas. Table Reporting Themes: Audio | Democracy & Inequality | Documentary | Health, Science & Environment | Investigative | Multimedia | Narrative Writing | Photojournalism | Shortform Video 1:00 pm - 1:30 pm Investigative Reporting Program Talk (Library) 1:30 pm - 2:15 pm Chat with IRP (IRP Offices across the street, 2481 Hearst Avenue - Drop-In) 2:15 pm - 3:00 pm Chat with the Dean (Dean’s Office - Drop-In) 3:00 pm - 4:00 pm Student Panel: The Student Perspective (Library) 4:00 pm - 5:00 pm Reception with current students, faculty & staff Classes (See Bios and Descriptions for more info) 9:00 am – Noon Reporting the News J200 Sections: Democracy & Inequality Instructor: Chris Ballard | Production Lab Health & Environment Instructor: Elena Conis -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Downloads/Aib Provincial Wait Times E.Pdf; 18, 2006)

Committee for Economic Development Comm 2000 L Street N.W., Suite 700 A StatementStatement bbyy tthehe Washington, D.C. 20036 RResearchesearch aandnd PPolicyolicy 202-296-5860 Main Number 202-223-0776 Fax CCommitteeommittee ooff tthehe 1-800-676-7353 CCommitteeommittee fforor EEconomicconomic DDevelopmentevelopment www.ced.org A Statement by the Research and Policy Committee of the Committee for Economic Development i Quality, Aff ordable Health Care for All Moving Beyond the Employer-Based Health-Insurance System Includes bibliographic references ISBN #0-87186-187-9 First printing in bound-book form: 2007 Printed in the United States of America COMMITTEE FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 2000 L Street, N.W., Suite 700 Washington, D.C., 20036 202-296-5860 www.ced.org Contents Purpose of Th is Statement . xi Executive Summary . 1 I. Introduction. 9 Why Another CED Statement on Health Care?. 9 Is the U.S. Health-Care System Failing? Performance Standards for a Nation’s Health-Care System . 10 Does the American Health-Care System Meet Th ese Standards? . 11 Why Is Employer-Based Health Insurance Declining?. 12 Th e Causes of High and Rising National Health Expenditures . 12 EBI Costs Cause Major Problems for Employers . 14 Employer Responses to Date Have Not Solved the Problem . 15 Buyers Cannot Hold Th eir Health Expenditure to Sustainable Growth Rates. 16 Conclusion . 18 II. Why 35 Years of “Band-Aids” on a Fundamentally Flawed System Did Not Work. 21 Why One Popular Idea – the Consumer-Directed Health Plan – Will Not Work. 24 Consumer Direction . 24 High-Deductible Health Insurance. 24 Why Canada’s “Single-Payer” System or “Medical Care for All” Will Not Solve Our Health-Care Problems. -

A Work Project Presented As Part of the Requirements for the Award of a Master’S Degree In

A Work Project presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master’s degree in Finance from the Nova School of Business and Economics. THERANOS: BETTING ON BLOOD DIOGO JESUS NETO Work project carried out under the supervision of: Paulo Pinho 06-01-2020 Abstract Theranos was a Silicon Valley start-up founded by Elizabeth Holmes in 2003. Holmes claimed to have developed a new blood-testing device that had the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry. She established partnerships with Walgreens and Safeway to make her technology available nationwide. She also secured a prestigious board of directors and an equally impressive investor base that raised over $700 million at a peak valuation of $9 billion. However, an investigation by The Wall Street Journal revealed the company had misled investors and endangered patients’ lives. In 2018, Theranos collapsed after years of battling lawsuits and federal charges. Keywords: Theranos, Corporate Governance, Fundraising, Due Diligence This work used infrastructure and resources funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (UID/ECO/00124/2013, UID/ECO/00124/2019 and Social Sciences DataLab, Project 22209), POR Lisboa (LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-007722 and Social Sciences DataLab, Project 22209) and POR Norte (Social Sciences DataLab, Project 22209). 1 Theranos: Betting on Blood “One of the most epic failures in corporate governance in the annals of American capitalism”. - John Carreyrou1 On June 28, 2019, a crowd of journalists awaited Elizabeth Holmes at the door of the San Jose Federal Court in California for a pre-trial hearing2. She was accused of engaging in a multi-million- dollar scheme to defraud investors, doctors, and patients alongside her former partner, Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani. -

Rethinking the Federal Securities Laws

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2003 Accountants Make Miserable Policemen: Rethinking the Federal Securities Laws Jerry W. Markham Florida International University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry W. Markham, Accountants Make Miserable Policemen: Rethinking the Federal Securities Laws, 28 N.C.J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 725, 812 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Jerry W. Markham, Accountants Make Miserable Policemen: Rethinking the Federal Securities Laws, 28 N.C.J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 725 (2003) Provided by: FIU College of Law Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue May 1 11:26:02 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device Accountants Make Miserable Policemen: Rethinking the Federal -

Read the 2018-2019 Shorenstein Center Annual Report

Annual Report 2018–2019 Contents Letter from the Director 2 2018–2019 Highlights 4 Areas of Focus Technology and Social Change Research Project 6 Misinformation Research 8 Digital Platforms and Democracy 10 News Quality Journalist’s Resource 12 The Goldsmith Awards 15 News Sustainability 18 Race & Equity 20 Events Annual Lectures 22 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics 23 Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press 33 Speaker Series 41 The Student Experience 43 Fellows 45 Staff, Faculty, Board, and Supporters 47 From the Director Like the air we breathe and the water we drink, the information we consume sustains the health of the body politic. Good information nourishes democracy; bad information poisons it. The mission of the Shorenstein Center is to support and protect the information ecosystem. This means promoting access to reliable information through our work with journalists, policymakers, civil society, and scholars, while also slowing the spread of bad information, from hate speech to “fake news” to all kinds of distortion and media manipulation. The public square has always had to contend with liars, propagandists, dividers, and demagogues. But the tools for creating toxic information are more powerful and widely available than ever before, and the effects more dangerous. How our generation responds to threats we did not foresee, fueled by technologies we have not contained, is the central challenge of our age. How do journalists cover the impact of misinformation without spreading it further? How do technology companies, -

The Bleeding Edge: Theranos and the Growing Risk of an Unregulated Private Securities Market

University of Miami Business Law Review Volume 28 Issue 2 Article 8 September 2020 The Bleeding Edge: Theranos and the Growing Risk of an Unregulated Private Securities Market Theodore O'Brien Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Theodore O'Brien, The Bleeding Edge: Theranos and the Growing Risk of an Unregulated Private Securities Market, 28 U. Miami Bus. L. Rev. 404 (2020) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr/vol28/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Business Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bleeding Edge: Theranos and the Growing Risk of an Unregulated Private Securities Market Theodore O’Brien* America’s securities laws and regulations, most of which were created in the early twentieth century, are increasingly irrelevant to the most dynamic emerging companies. Today, companies with sufficient investor interest can raise ample capital through private and exempt offerings, all while eschewing the public exchanges and the associated burdens of the initial public offering, public disclosures, and regulatory scrutiny. Airbnb, Inc., for example, quickly tapped private investors for $1 billion in April of 2020,1 adding to the estimated $4.4 billion the company had previously raised.2 The fundamental shift from public to private companies is evidenced by the so-called “unicorns,” the more than 400 private companies valued at more than $1 billion. -

Who Watches the Watchmen? the Conflict Between National Security and Freedom of the Press

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

Sarah Clemens* Journalists Face a Credibility Crisis, Plagued by Chants

FROM FAIRNESS TO FAKE NEWS: HOW REGULATIONS CAN RESTORE PUBLIC TRUST IN THE MEDIA Sarah Clemens* Journalists face a credibility crisis, plagued by chants of fake news and a crowded rat race in the primetime ratings. Critics of the media look at journalists as the problem. Within this domain, legal scholarship has generated a plethora of pieces critiquing media credibility with less attention devoted to how and why public trust of the media has eroded. This Note offers a novel explanation and defense. To do so, it asserts the proposition that deregulating the media contributed to the proliferation of fake news and led to a decline in public trust of the media. To support this claim, this Note first briefly examines the historical underpinnings of the regulations that once made television broadcasters “public trustees” of the news. This Note also touches on the historical role of the Public Broadcasting Act that will serve as the legislative mechanism under which media regulations can be amended. Delving into what transpired as a result of deregulation and prodding the effects of limiting oversight over broadcast, this Note analyzes the current public perception of broadcast news, putting forth the hypothesis that deregulation is correlated to a negative public perception of broadcast news. This Note analyzes the effect of deregulation by exploring recent examples of what has emerged as a result of deregulation, including some of the most significant examples of misinformation in recent years. In so doing, it discusses reporting errors that occurred ahead of the Iraq War, analyzes how conspiracy theories spread in mainstream broadcast, and discusses the effect of partisan reporting on public perception of the media. -

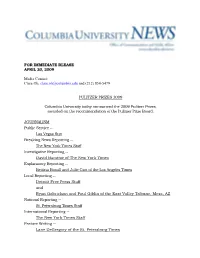

Office of Public Information

FOR IMMEDIATE RLEASE APRIL 20, 2009 Media Contact: Clare Oh, [email protected] and (212) 854-5479 PULITZER PRIZES 2009 Columbia University today announced the 2009 Pulitzer Prizes, awarded on the recommendation of the Pulitzer Prize Board. JOURNALISM Public Service -- Las Vegas Sun Breaking News Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Investigative Reporting -- David Barstow of The New York Times Explanatory Reporting -- Bettina Boxall and Julie Cart of the Los Angeles Times Local Reporting -- Detroit Free Press Staff and Ryan Gabrielson and Paul Giblin of the East Valley Tribune, Mesa, AZ National Reporting -- St. Petersburg Times Staff International Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Feature Writing -- Lane DeGregory of the St. Petersburg Times Commentary -- Eugene Robinson of The Washington Post Criticism -- Holland Cotter of The New York Times Editorial Writing -- Mark Mahoney of The Post-Star, Glens Falls, NY Editorial Cartooning -- Steve Breen of The San Diego Union-Tribune Breaking News Photography -- Patrick Farrell of The Miami Herald Feature Photography -- Damon Winter of The New York Times LETTERS AND DRAMA Fiction -- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout (Random House) Drama -- Ruined by Lynn Nottage History -- The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed (W.W. Norton & Company) Biography -- American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham (Random House) Poetry -- The Shadow of Sirius by W. S. Merwin (Copper Canyon Press) General Nonfiction -- Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon (Doubleday) MUSIC Double Sextet by Steve Reich, premiered March 26, 2008 in Richmond, VA (Boosey & Hawkes). -

Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner

American University Law Review Volume 61 | Issue 5 Article 3 2012 Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner Jeanne Theoharis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Rovner, Laura, and Jeanne Theoharis. "Prefering Order to Justice." American University Law Review 61, no.5 (2012): 1331-1415. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prefering Order to Justice This essay is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol61/iss5/3 ROVNER‐THEOHARIS.OFF.TO.PRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 6/14/2012 7:12 PM PREFERRING ORDER TO JUSTICE ∗ LAURA ROVNER & JEANNE THEOHARIS In the decade since 9/11, much has been written about the “War on Terror” and the lack of justice for people detained at Guantanamo or subjected to rendition and torture in CIA black sites. A central focus of the critique is the unreviewability of Executive branch action toward those detained and tried in military commissions. In those critiques, the federal courts are regularly celebrated for their due process and other rights protections. Yet in the past ten years, there has been little scrutiny of the hundreds of terrorism cases tried in the Article III courts and the state of the rights of people accused of terrrorism-related offenses in the federal system.