Pedagogy and Learning Technology: a Practical Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Created with Deskpdf PDF Writer

Common Windows file extensions | IT Services https://it.nmu.edu/docs/common-windows-file-extensions Documentation » Common Windows file extensions Search Chat is offline. Windows file names have two parts; the file's name, then a period followed by the Email Us extension (suffix). The extension is a three- or four-letter abbreviation that signifies (906) 227-2468 the file type. For example, in letter.docx the filename is letter and the extension is [email protected] docx . Extensions are important because they tell your computer what icon to use for the file, and what application can open the file. For example, the doc extension tells your computer that the file is a Microsoft Word file. If you want to open a MAC OS X file in Windows, you may need to add the extension to a MAC OS X file name so Windows can recognize it. For example, if Located in LRC 116 you have a Word 6 MAC OS X document named letter that you want to open in Across from Fieras Windows, you need to rename the file letter.docx so that Word in Windows will recognize and open the file. List of File Extensions Showing File Extensions Searching File Extensions Note: This list is by no means a complete and exhaustive list of file extensions. If the file extension you are using is not listed below, you may find the information by looking in the software manual or software application's Web site. Note: If none of your file names have extensions, file extensions are hidden. -

H%RRNV ,GHD WR Amazon in 14 Days

eBooks: Idea to Amazon in 14 Days Release Your Cutting Edge Business Reports, Strategic Training & How-To Materials plus Manuscripts in Every Genre & by Any Author “Jam-packed with resources for my next project, from legal tips, to trusted freelancers, to helpful timelines... Marnie shares it all.” Shelley Hitz, Author/Speaker “What a great book! eBooks: Idea to Amazon in 14 Days includes a straightforward, simple approach to writing an eBook. The steps from paper to publisher are crystal clear. Thank you Marnie!” Andrea Sharp, Public Speaker "EBooks are the future of reading and Marnie's book provides clear, concise and easy to follow steps for authors who are serious about getting published. Her step-by-step directions are helping me make my dream of writing a reality. A truly helpful resource." Michelle Reynolds, CEO, Accel365 “A fast-read destined to help many writers get their work in print and on the market in record time.” Donna Best, Public Speaker “Marnie again and again turns vague ideas into concrete action plans, mapping the way from dreams to success. I have no doubt my book will be better because of what I’ve learned from you. I am excited to use some of your tips on my job as well.” Marla Hartson, Project Manager How to See Your Book on Amazon Fast eBooks: Idea to Amazon in 14 Days by Leadership Mentor Marnie Swedberg www.Marnie.com 3 eBooks: Idea to Amazon in 14 Days Copyright © 2010 by Marnie Swedberg http://www.marnie.com Cover Design by Erin Adler Lauren Graphics, Inc. -

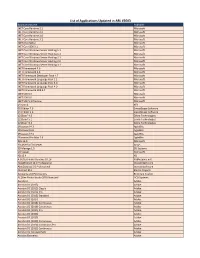

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2583

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2583 Application Name Publisher 1099 Express 2019 Enterprise 1099Express.com Lightyear 1.5 3D Systems DICOM to Print 3D Systems Extension for SketchUp 5.1 3Dconnexion Plug-In for NX 8.0 3Dconnexion 3DxWinCore 17.7 3Dconnexion Navigation Library Server 1.4 3Dconnexion Plug-In for 3ds Max 7.0 3Dconnexion Plug-In for Maya 6.0 3Dconnexion Plug-In for Photoshop 2.9 3Dconnexion DriveSize 5.6 ABB LinkOne WebView 3.24 ABB REX640 IED Connectivity Package 1.1 ABB ARXivar Client Able Tech ARXivar Server Able Tech a³ for C 19.10 AbsInt a³ for C 18.04 AbsInt AccuTerm 7.0 AccuSoft RTCA Software 2.3 Pro ACEA BIO MP3 Audio Mixer Acoustica ExtremeZ-IP File Server Acronis ExtremeZ-IP Print Server Acronis SPiiPlus ADK Suite 2.50 ACS Motion Control Pervasive.SQL 7.0 Actian Versant Developer Suite 6.0 Actian NoSQL 7.0 Actian Active Collab Timer 1.7 ActiveCollab Network Monitor ActiveXperts ADDIPACK 1.4 ADDI-DATA Microsoft Information Protection (MIP) Plug-in for Acrobat Reader 20.0Adobe PDF Broker Process for Internet Explorer 20.1 Adobe Collaboration Synchronizer 20.13 Adobe Photoshop Elements 2021 Adobe Premiere Elements 2021 Adobe Super Mouse Auto Clicker 4.1 ADVANCED MOUSE AUTO CLICKER MassHunter Mass Profiler Agilent Technologies MicroLab (FTIR) Agilent Technologies MicroLab (FTIR) 5.4 PC Agilent Technologies Dissolution Workstation Agilent Technologies ICP Expert 7.4 Agilent Technologies ICP Expert 7.3 Agilent Technologies MassHunter DAR Calculator 2.1 Agilent Technologies MassHunter LC/SQ ChemStation Integration -

Guide Méthodologique Les Outils De Conversion Vers Le Format PDF

NUMEN-SIAF-HUMANUM-CINES-GM-OCPDF-1.0 Guide méthodologique Les outils de conversion vers le format PDF Guide Méthodologique Les outils de conversion vers le format PDF : traitement de texte, dessins techniques, édition scientifique Version: 1.0 Date: 14/01/2014 Document: NUMEN-SIAF-HUMANUM-CINES-GM-OCPDF-1.0 Confidentialité: Public NUMEN-SIAF-HUMANUM-CINES-GM-OCPDF-1.0 Guide méthodologique Les outils de conversion vers le format PDF Table des Matières 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PERIMETRE DE L’ETUDE .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2 TYPES D’OUTILS DE CONVERSION ........................................................................................................ 3 2.1 TYPE 1 : PLUG-IN DU LOGICIEL ORIGINAL ................................................................................................... 3 2.2 TYPE 2 : CONVERSION DEPUIS LE FICHIER SOURCE ..................................................................................... 4 2.3 TYPE 3 : PILOTE D’IMPRESSION ................................................................................................................... 5 2.4 TYPE 4 : CONVERTISSEUR POSTSCRIPT ...................................................................................................... -

Precision Farming Technique for Water Resource Management

PRECISION FARMING TECHNIQUE FOR WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT THESIS SUBMIHED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of $l)ilD£(opI)p (N Agricultural Economic and Business Management BY AARIF MOHAMMAD KHAN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR, SAGHIR AHMAD ANSARI DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT AUGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 (INDIA) 2013 3 1 OCT 2014 T8823 DEPARtMENT OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS & BUSINESS MANAGEMENT SHAFl HOUSE, 2-QlLA ROAD, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSfTY ALIGARH-2p2002 (INDIA) CHAIRMAN CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled "Precision Farming iJechnique for Water Resource Management" has been completed by Mr. *k.arif Mohammad Khan under my supervision. I have allowed him to submit |t in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. To the best of my knowledge the thesis work is original and done by the candidate himself. (Dr. Saghir Ahmad Ansari) Tele Fax.- 91-571-2702238, Internal: 3755, Fax: 91-0571-2702238 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Looking back, I am surprised and at the same time very grateful for all I have received throughout these years. It has certainly shaped me as a person and has led me where I am now. All these years of PhD studies are full of such gifts. The first and foremost "thank you" goes to Allah. He has given me the strength and mind opening to see this study through. Without his care, blessings and guidance, none of this would have been possible It would be sheer ignorance and arrogance to believe that any work of research can he an individual endeavour. -

Diplomsko Delo

VIŠJA STROKOVNA ŠOLA ACADEMIA, MARIBOR DIPLOMSKO DELO TEHNOLOGIJA NASTANKA ELEKTRONSKE RAZLIČICE KNJIGE IN ANALIZA NJENE UPORABE Priimek in ime: Nataša Zemljič Št. indeksa: 11190122769 Program: Multimediji Leto vpisa: 2007/08 Mentor: Mag. Branko Namestnik Maribor, december 2009 IZJAVA O AVTORSTVU Podpisana Nataša Zemljič, št. indeksa 11190122769, izjavljam, da sem avtor diplomske naloge z naslovom Tehnologija nastanka elektronske različice knjige in analiza njene uporabe, ki sem jo napisala pod mentorstvom mag. Branka Namestnika. S svojim podpisom zagotavljam, da: - je priložena diplomska naloga izključno rezultat mojega dela, - sem poskrbela, da so dela in mnenja drugih avtorjev, ki jih uporabljam v priloženi nalogi navedena oz. citirana skladno s pravili Višje strokovne šole Academia, Maribor - se zavedam, da je plagiatorstvo – predstavljanje tujih del oz. misli, kot moje lastne – kaznivo po Zakonu o avtorstvu in sorodnih pravicah; UL. št. 16/2007; (v nadaljevanju ZASP), prekršek pa podleže tudi ukrepe VSŠ Academia skladno z njenimi pravili, - skladno z 32. členom, ZASP, dovoljujem VSŠ Academia objavo diplomske naloge na njenem spletnem portalu. Maribor, december 2009 Podpis študenta: 2 ZAHVALA Najprej bi se zahvalila svoji družini, ki je z razumevanjem spremljala mojo odstotnost med pisanjem tega diplomskega dela in mi nudila vso potrebno podporo. Hvala celotnemu kolektivu Academie, predvsem mag. Ireni Bedrač, od katere sem se veliko naučila o svetu medijev, ter tudi ravnateljici mag. Mirjani Ivanuša-Bezjak, ki mi je vedno nesebično priskočila na pomoč. Še posebej sem hvaležna svojemu mentorju mag. Branku Namestniku za vse koristne informacije, usmerjanje in vso ostalo strokovno pomoč, ki mi jo je nudil skozi celoten proces nastajanja diplome. Zahvala tudi lektorici prof. -

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2603

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2603 ApplicationName Publisher .NET Core Runtime 2.1 Microsoft .NET Core Runtime 2.2 Microsoft .NET Core Runtime 3.0 Microsoft .NET Core Runtime 3.1 Microsoft .NET Core SDK 2 Microsoft .NET Core SDK 3.1 Microsoft .NET Core Windows Server Hosting 1.1 Microsoft .NET Core Windows Server Hosting 1.1 Microsoft .NET Core Windows Server Hosting 2.1 Microsoft .NET Core Windows Server Hosting 2.2 Microsoft .NET Core Windows Server Hosting 3.1 Microsoft .NET Framework 4.0 Microsoft .NET Framework 4.6 Microsoft .NET Framework Developer Pack 4.7 Microsoft .NET Framework Language Pack 1.1 Microsoft .NET Framework Language Pack 3.0 Microsoft .NET Framework Language Pack 4.0 Microsoft .NET Framework SDK 4.7 Microsoft .NET SDK 5.0 Microsoft .NET SDK 5.0 Microsoft .NET SDK 5.1 Preview Microsoft µVision 4 KEIL 010 Editor 7.0 SweetScape Software 010 Editor 9.0 SweetScape Software 123Scan² 4.5 Zebra Technologies 123Scan² 5.1 Zebra Technologies 123Scan² 5.2 Zebra Technologies 1Password 4.3 AgileBits 1Password 6.8 AgileBits 1Password 7.1 AgileBits 1Password for Mac 7.6 AgileBits 365 16.0 Microsoft 3D ANSYS CFD Viewer Ansys 3D Manage 1.5 3D Systems 3D Viewer Microsoft 4D 15.4 4D A Better Finder Rename 10.16 Publicspace.net Able2Extract 14.0 Professional Investintech.com Able2Extract 5.0 Professional Investintech.com Abstract 85.1 Elastic Projects Accounts and Permissions Beckman Coulter ACDSee Photo Studio 2018 Standard ACD Systems Acrobat 1 Adobe Acrobat DC (2015) Adobe Acrobat DC (2015) Classic Adobe Acrobat DC (2015) -

Himmelfarb Headlines (2009 - Present) Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Himmelfarb Headlines (2009 - present) Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library 5-2011 Himmelfarb Headlines - May/June 2011 George Washington University, Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library Follow this and additional works at: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/headlines Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation George Washington University, Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, "Himmelfarb Headlines - May/June 2011" (2011). Himmelfarb Headlines (2009 - present). Paper 4. http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/headlines/4 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himmelfarb Headlines (2009 - present) by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Himmelfarb Headlines - May / June 2011 Home About Information Interface Ask Us 2011 E-Newsletters Himmelfarb Headlines - May / June 2011 May / June 2011 Inside this Edition... February / March 2011 Director's Desk 2010 E-Newsletters Faculty Profile - Linda Werling, PhD: Associate Dean for Graduate Education in the School of Medicine, Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Physiology November / December 2010 Tool of the Quarter - Health Policy Reference Center September / October 2010 How Do You Highlight and Add Notes to Web Pages, E-Texts and PDFs? It's Easy! Meet Yvonne Lee, Himmelfarb Library Collections Coordinator Archived Newsletters and Leader of a Greener Interlibrary Loan (Information Interface) Director's Desk From the Director's Desk The 2010/11 Academic Year saw lots of changes from the launch of health care reform and the expanding use of handheld computing and electronic health records on the national level to the creation of new programs in mobile health and health information technology on campus.