Kim Kashkashian Sarah Rothenberg Steven Schick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Concert Programs

The Beethoven Experience Part V: B.A.C.H.D.N.A Beethoven’s Love of Bach- Examined and Expressed Don't miss a note of our 48 concert virtual festival: VIEW FULL CONCERT SCHEDULE @HEIFETZMUSIC @HEIFETZMUSIC @HEIFETZINTERNATIONALMUSICINSTITUTE WWW.HEIFETZINSTITUTE.ORG T H E P R O G R A M String Quartet No. 3 in D major, Op. 18, No. 3 I. Allegro II. Andante con moto III. Allegro IV. Presto Recorded at Suntory Hall - Tokyo, Japan June 2013 String Quartet No. 9 in C major, Op. 59, No. 3 I. Andante con moto – Allegro vivace II. Andante con moto quasi allegretto III. Menuetto (Grazioso) IV. Allegro molto Recorded at Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum - Boston, MA April 2010 THE BORROMEO STRING QUARTET NICHOLAS KITCHEN, KRISTOPHER TONG, VIOLINS MAI MOTOBUCHI, VIOLA YEESUN KIM, CELLO P R O G R A M N O T E S by Benjamin K Roe B.A.C.H.D.N.A: Beethoven’s Love of Bach - Examined and Expressed “His name ought not to be Bach, but Ocean, because of his infinite and inexhaustible wealth of combinations and harmonies.” - Beethoven "The immortal god of harmony." Just as Nicholas Kitchen has so persuasively demonstrated Beethoven's careful and deliberate use of underlines in the expressive markings of his manuscripts, so too did he add underlines to his correspondences when he wanted to make a particularly emphatic point, as he did about Bach in an 1801 letter to his publishers, the storied Leipzig firm of Breitkopf & Härtel. As evidenced by the two quotes above, Beethoven’s admiration for Bach was well-known in his time; the “not Bach, but Ocean” is a play on the German word, as Bach translates as a “small brook,” such as might flow from a wellspring. -

Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 3 at 8:00pm Sieben frühe Lieder (1905-08) Dolce Cantavi (2015) Alban Berg Caroline Shaw Born February 9, 1885 Born August 1, 1982 Died December 24, 1935 Duration: approx. 3 minutes Duration: approx. 15 minutes Marlboro premiere Last Marlboro performance: 1997 Berg’s Sieben frühe Liede, literally “seven early songs,” As she has done in other works such as her piano were written while he was still a student of Arnold concerto for Jonathan Biss, which was inspired by Schoenberg. In fact, three of these songs were premiered Beethoven’s third piano concerto, Shaw looks into music in a concert by Schoenberg’s students in late 1907, history to compose music for the present. This piece in around the time that Berg met the woman whom he particular eschews fixed meter to recall the conventions would marry. In honor of the 10-year anniversary of this of early music and to highlight the natural rhythms of the meeting, he later revisited and corrected a final version of libretto. The text of this short but wonderfully involved the songs. The whole set was not published until 1928, song is taken from a poem by Francesca Turini Bufalini when Berg arranged an orchestrated version. Each song (1553-1641). Not only does the language harken back to features text by a different poet, so there is no through- an artistic period before our own, but the music flits narrative, however the songs all feature similar themes, through references of erstwhile luminaries such as revolving around night, longing, and infatuation. -

Current Review

Current Review Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Complete String Trios aud 97.773 EAN: 4022143977731 4022143977731 American Record Guide (2021.01.01) Mozart’s Divertimento K 563 is widely regarded as the finest string trio ever written. It is in 6 movements rather than the usual 4, and the title is Divertimento, but don’t let those aspects of the work turn you off to it; it is not a mere diversion. It has some of Mozart’s loveliest writing for strings. It is also one of his longest chamber works, clocking in at threequarters of an hour. I assure you that Mozart didn’t pad the material to fill time, either. Every note counts. Jacques Thibaud String Trio was founded in 1994 at the Arts University in Berlin. Their current membership is violinist Burkhard Mais, violist Hannah Strijbos, and cellist Bogdan Jianu. They play well together and perform this work with more taste and sense of proportion than some other groups I’ve heard. I can recommend this performance, but they are up against stiff competition. Isaac Stern, Pinchas Zukerman, and Leonard Rose made a very fine recording in 1975. Gidon Kremer, Kim Kashkashian, and Yo-Yo Ma made a wonderful recording in 1985. That is my favorite. It is exquisitely polished yet very soulful. The musicians really sing and produce ravishing sounds (unusual for the perpetual enfant-terrible Kremer). The classic recording is by Jascha Heifetz, William Primrose, and Emanuel Feuermann from 1941. It shows its age, yet it is the most brilliant ever made. Some may not like it because of the exhibitionism of the players, all of whom were the greatest virtuosos of their age, but I like hearing such assured playing where all technical obstacles are surmounted with effortless aplomb and panache. -

An Evening with Parker Quartet

An Evening with Parker Quartet Daniel Chong, violin Ying Xue, violin Jessica Bodner, viola Kee-Hyun Kim, cello With special guests Jung-Ja Kim, piano and Charles Clements, double bass Mozart String Quartet No. 22 in B-flat major, K.589 Allegro Larghetto Menuetto: Moderato Allegro assai Prokofiev String Quartet No.2 in F major, Op. 92 Allegro sostenuto Adagio Allegro Intermission Schubert Piano Quintet in A major, D. 667 “Trout” Allegro vivace Andante Scherzo: Presto Andantino – Allegretto Allegro giusto Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) String Quartet No. 22 in B-flat major, K.589 (1790) Mozart's greatest contribution to the string quartet repertoire dates from 1782 and 1785, the period during which he composed the six quartets dedicated to his friend Joseph Haydn. Only four quartets follow them, the lone K. 499 in D major, composed in 1786 and known as the "Hoffmeister" quartet, and the three quartets known as the "Prussian" quartets. They owe their name and genesis to what has generally assumed to have been a commission for six quartets from King Frederick William II of Prussia. The king, a keen amateur cellist, had received Mozart at Potsdam during the visit of the latter in the spring of 1789. After Mozart returned to Vienna he quickly completed the first of the quartets, K. 575 in D, but thereafter made no further attempt to add to Frederick William's quartets for another year. Mozart's dilatory attitude to proceeding with the set may be in part accounted for by the commission he and his librettist Lorenzo da Ponte received for Così fan tutte, which probably arrived late in the summer of 1789. -

TRIO GASPARD Jonian Ilias Kadesha Violin Vashti Hunter Cello Nicholas Rimmer Piano

TRIO GASPARD Jonian Ilias Kadesha Violin Vashti Hunter Cello Nicholas Rimmer Piano "A truly refreshing performance! Richly coloured, honest, full of joy and with good agogics! This trio belongs to another league!" Ensemble Magazine Founded in 2010, Trio Gaspard are one of the most sought- after piano trios of their generation, praised for their unique and fresh approach to the score. Trio Gaspard are regularly invited to perform at major international concert halls, such as Wigmore Hall, Berlin Philharmonie, Essen Philharmonie, Grafenegg Castle Austria, Salle Molière Lyon, NDR Rolf- Liebermann Hall, Hamburg and Shanghai Symphony Hall as well as making appearances at festivals such as Heidelberger Frühling, Mantua Chamber Music Festival, Boswiler Sommer and PODIUM Festival Esslingen. Important engagements over the past year include recitals in Belfast, Trieste, Naples, Bern, Heidelberg, Grafenegg Festspiele as well as at Berlin’s ‘Pierre Boulez’ Saal. A highlight of 2018 was performing Beethoven triple concerto twice in Switzerland under the baton of eminent musician and conductor, Gabor Takács-Nagy. Trio Gaspard are winners of three major international competitions since their inception. They won first prizes and special prizes at the International Joseph Joachim Chamber Music Competition in Weimar, the 5th International Haydn Chamber Music Competition in Vienna and the 17th International Chamber Music Competition in Illzach, France. In 2012 they were awarded the “Wiener Klassik” Preis der Stadt Baden in Austria. As well as exploring and championing the traditional piano trio repertoire, Trio Gaspard works regularly with contemporary composers and is keen to discover seldom-played masterpieces. In 2017, they performed a commission from Irish composer Gareth Williams at the Belfast Music Society, broadcasted live by the BBC. -

Music Business in Detroit

October 18, 2013 Music Business in Detroit: Estimating the Size of the Music Industry in the Motor City Prepared by: Anderson Economic Group, LLC Colby Spencer Cesaro, Senior Analyst Alex Rosaen, Senior Consultant Lauren Branneman, Senior Analyst Forward by: Patrick L. Anderson, Principal & CEO Anderson Economic Group, LLC 1555 Watertower Place, Suite 100 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 Tel: (517) 333-6984 Fax: (517) 333-7058 www.AndersonEconomicGroup.com © Anderson Economic Group, LLC, 2013 Permission to reproduce in entirety granted with proper citation. All other rights reserved. Foreword I'm pleased to share with readers of Crain's Detroit Business, as well as with others in the Detroit region, this first-of-its-kind study of the business of music in southeast Michigan. Everyone that grew up in this area knows of the "Motown sound," as well as the heritage of jazz, blues, and rock that has steeped into our culture. Many of us are also aware of the more recent innovations of techno and hip-hop, much of which has roots in Detroit. However, until now there has been no systematic analysis of the business of music in our area. Our Anderson Economic Group consultants have combed census and other business records; examined the geographic pattern of nightclubs and perfor- mance venues; scanned demographic patterns for concentrations of heavy enter- tainment consumers; and even conducted primary research into the days/nights of live music available to metro Detroiters at over two hundred specific bars, taverns, and clubs. What we have assembled is a thorough analysis of an indus- try that has always been important to our culture, but can now also be known for its contributions to our employment and earnings. -

2020 Concert Programs

The Beethoven Experience Speaking to God: Beethoven’s Spirituality, Explored & Expressed Don't miss a note of our 48 concert virtual festival: VIEW FULL CONCERT SCHEDULE @HEIFETZMUSIC @HEIFETZMUSIC @HEIFETZINTERNATIONALMUSICINSTITUTE WWW.HEIFETZINSTITUTE.ORG T H E P R O G R A M STRING QUARTET NO. 2 IN G MAJOR , OP. 18 NO. 2 I. ALLEGRO II. ADAGIO CANTABILE - ALLEGRO - TEMPO I III. SCHERZO: ALLEGRO IV. ALLEGRO MOLTO, QUASI PRESTO STRING QUARTET NO. 8 IN E MINOR, OP. 59, NO. 2 "RAZUMOVSKY" I. ALLEGRO II. MOLTO ADAGIO III. ALLEGRETTO. MAGGIORE - THEME RUSSE IV. FINALE. PRESTO THE BORROMEO STRING QUARTET NICHOLAS KITCHEN, KRISTOPHER TONG, VIOLINS; MAI MOTOBUCHI, VIOLA; YEESUN KIM, CELLO P R O G R A M N O T E S by Benjamin K Roe The Beethoven Experience III: Speaking to God "Most heavenly music! It nips me unto listening, and thick slumber hangsupon mine eyes." - Shakespeare, Pericles The first book ever devoted entirely to the subject of Beethoven's string quartets appeared in 1885, from German musicologist Theodor Helm. It was titled "Beethoven's String Quartets: An Attempt at a Technical Analysis of these Works in Association with their Spiritual Content. "The title may sound quaint in modern times, where it has become fashionable for contemporary music theorists to disdain the interpretations of their 19th-century predecessors as "Solemn Germans breathing philosophical hot air." Yet in Beethoven, a true child of the Enlightenment, (which is to say a believer in Christianity but not theocracy), there is a surprisingly powerful thread of spirituality and faith that runs throughout his sixteen quartets. -

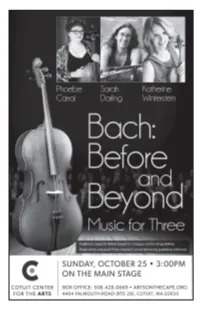

Bach-Before-And-Beyond-10-25-20.Pdf

Bach Before and Beyond Music for Three Katherine Winterstein, Violin Sarah Darling, Viola Phoebe Carrai, Cello Sunday, October 25th at 3:00 pm Henry Purcell (1659-1695) 3 Fantasias Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) String Trio- opus 38 no.2 in D Major Andantino moderator assai- Tempo di Minuetto and Trio Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart / Johann Sebastian Bach (1756-1791) (1685-1750) Sechs Langsame Sätze und Dreistimmige Fugen (Six slow movements and 3 voiced fugues) K404A - No.4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento no.3 in B-flat Major Allegro - Larghetto - Menuetto - Adagio - Rondo allegretto Katherine Winterstein: Praised by critics for playing that is “as exciting as it is beautiful,” and for “livewire intensity” that is both “memorably demonic” and “delightfully effective,” violinist Katherine Winterstein enjoys a wide range of musical endeavors, as a chamber musician, orchestral musician, soloist, and teacher. Ms. Winterstein is the concertmaster of the Vermont Symphony, the associate concertmaster of the Rhode Island Philharmonic, and she is co-concertmaster of the Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra. In recent seasons she has also performed frequently with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, the Handel and Haydn Society, and A Far Cry. She is a member of the Hartt String Quartet, the Providence-based Aurea Ensemble, and the summer of 2020 would have been her 19th with the Craftsbury Chamber Players of Vermont. She has also performed with Boston-based Chameleon Arts Ensemble, Radius Ensemble, and Dinosaur Annex. She has appeared as soloist with several orchestras including the Vermont Symphony, the Wintergreen Festival Orchestra, the Charlottesville Symphony, the Champlain Philharmonic, and the Boston Virtuosi. -

Cavani String Quartet

Cavani String Quartet Described by the Washington Post as “completely engrossing powerful and elegant” The Cavani Quartet has dedicated its artistic life to communicating the joy of discovery in the service of some of the most powerful music ever written. "Their artistic excellence, their generous spirit, and their fervent ambassadorship for great music make them unique among America's greatest string quartets. They may be the single most valuable role model for the classical chamber music field in our time, an inspiration to fellow musicians and audiences across the country." ~Detroit Chamber Music Society The quartet's musical career maintains an energetic balance between performing masterpieces by composers such as Mozart, Beethoven and Bartok; collaborating with living composers including Joan Tower and Margaret Brouwer; and creating new programming that joins multiple disciplines, such as visual art, poetry, and dance.The quartet’s motivation to interact with all audiences enhances their approach to performing, teaching and mentoring. The Cavani Quartet is thrilled to shape the musical lives of the next generation through seminars that feature audience engagement and a "team -work" approach to rehearsal techniques. The empathy and connectivity of chamber music is recognized by the Cavani Quartet as a metaphor for the kind of communication that we should strive for between cultures and nations. Formed in 1984, the Cavani Quartet has toured throughout all fifty states, performing at some of the worlds most prestigious festivals, and series including The Aspen Music Festival, The New World Symphony, Norfolk Chamber Music Festival, Kniesel Hall, Interlochen Center for the Arts, Madeline Island Music Festival, The Chautauqua Festival, Encore Chamber Music and The Perlman Music Program. -

A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest Chin Wei Chang University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest Chin Wei Chang University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chang, C.(2018). A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5036 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest by Chin Wei Chang Bachelor of Music National Sun Yat- sen University, 2010 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2015 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Daniel Sweaney, Major Professor Kunio Hara, Committee Member Craig Butterfield, Committee Member Ari Streisfeld, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Chin Wei Chang, 2018 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my dearest parents, San-Kuei Chang and Ching-Hua Lai. Thank you for all your support and love while I have pursued my degree over the past six years. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I truly appreciate the director of the dissertation, Dr. Daniel Sweaney, for his advice, inspiration, and continuous encouragement over the past four years. -

2021 Program

This organization is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the SC Arts Commission. Thirteen Years of Joye in Aiken In this year of change, when it has sometimes seemed as if nothing might ever be normal again, one thing that has not changed is the importance of the arts in our lives. Especially where sources of hope and inspiration are few, the arts retain their power to energize and refresh us. And so it is with even greater pleasure than usual that we welcome you (digitally, to be sure) to the 13th Annual Joye in Aiken Festival and Outreach Program. Though COVID-19 has forced us to rethink timeframes, formats and venues in the interest of ensuring the safety of our community and our artists, we have embraced those challenges as opportunities. If a single Festival week presented dangers, could we spread the events out to allow for responses to changing conditions? If it wasn’t possible to hold an event indoors, could we hold it outdoors? With those questions and a thousand others answered, we are proud to present to you a Festival that is necessarily different in many respects, but that is no less exciting. And because it’s so central to our mission, we’re especially proud to introduce to you an important new dimension of our Outreach Program. With COVID making it impossible for us to present our usual Kidz Bop and Young People’s Concerts, we turned to our nationally-known artists for help. And their solution was perfect: two engaging series of instructional videos designed specifically for the children of Aiken County by these world-class musicians. -

Violin, Viola, Cello

6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 1 The Board of the California Music Center would like to express our special thanks to Elizabeth Chamberlain a great friend of the Klein Competition. Her deep appreciation of music and young artists is an inspiration to all of us. 1 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 2 The California Music Center and San Francisco State University present The Twenty-Third Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition June 11-15, 2008 with distinguished judges: Peter Gelfand Alan Grishman Marc Gottlieb Jennifer Kloetzel Patricia Taylor Lee Melvin Margolis Donna Mudge Alice Schoenfeld Franks Stemper First Prize: $10,000 The Irving M. Klein Memorial Award Second Prize: $5,000 The William M. Bloomfield Memorial Award Third Prize: $2,500 The Alice Anne Roberts Memorial Award Fourth Prizes: $1,500 The Thomas and Lavilla Barry Award The Jules and Lena Flock Memorial Award Additional underwriting provided by cgrafx, Inc., marketing & design Allen R. and Susan E. Weiss Memorial Prize: $200 For best performance of the commissioned work Each semifinalist not awarded a named prize will receive $1,000. 2 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 3 In Memoriam Warren G. Weis 1922-1995 Warren G. Weis was a long-time supporter of the California Music Center and the Irving M. Klein International String Competition. He took great delight in music and his close association with musicians and teachers, and supported the aspirations of young musicians withs generosity and enthusiasm. Bill Bloomfield 1918-1998 A member of the Board of the Competition, Bill Bloomfield was an amateur musician and a lifelong supporter sand enthusiast of music and the arts.