The Kilmichael Ambush - a Review of Background, Controversies and Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hen the Streams Overflow

--",41000,-**-% 44111111.11111111 k cow 1140 ocf cow 1270'. ilst cow 1025: f cow ocf cow 870 0 k cow 9150',1 1060'. )1.stcow 970' f cow 1075 d cow 890 0 k < cow 920 0 BULLS fbull 760 0 k bull 1255 0 1 f bull 1335 0r f bull 1050 0 STOCK PIGS white shts nixed shts ed pigs mixed pigs 61 white pigs 1 white pigs mixed pigs red pigs white pigs MMISSIO NY alongocno HEAP? throughtrom wif flood watersrry just ibarely gvered S closed; one carstalled 0 The highway was I thousands of acres in the area. parallels the high The railroad which n the water wasalmost covered. allay was washedout in one place. i MOVING TOHIGHER GROUND Alan and Ralph Larson help theirfather Howard 0. 1.44 flooded feel lotnear Tescott. Cattle Larson move dairystock from were moved to a pastureon higher ground. 1.10 Inc ANSI 13700 hen TheStreamsOverflow 1510 0: Co.- At*, 1709" Co. 14 ice Co. G&G area farmerscouldn't complain about not getting enough moisture ;0. @3 May. It wasa month that producedmore than its share of tornado warnings, aline Co. steady processionof grey days, some hail storms that devastated pockets of ay Co. G&G area, andfinally an accumulation of rainfall that 1065 @ ut of their banks. sent many streams 930@i Some of the places thatgot the worst of it are shown here a onpage 14, with pictures 10950:. by Kenneth Greene. o. 11700 ;0. 1320@ ;0. 1170@ ;o. 12400 th Co. 1115P 'ion Co. 1140@ 9250 Co. -

Behind the Veil in Ireland

Tlhe 1 i Ford. international Weekly J THE BlAUB DM I M DEPEMBENT a' $1.50 igj Dearborn, Michigan, July 16, 1921 fen Cents Behind the Veil in Ireland is the bra in center lieve from what they Irish movement. I By told me that DUBLIN ALEXANDER IRVINE Sinn Fein and the I. R. A. over there a few are in solid agreement as to weeks ago to find out what men the present The Irish question is every editor's nightmare. Nothing was ever written methods. There are a considerable were thinking about. What they about it which to bring failed denunciation from one side or the other. Alex. number of Irish people who de- do is the result of what they think. Irvine, Irish by birth, American by choice, went over to see he could if see it plore and stand out against mur- 1 was born in Ireland but I found steadily and see it whole. Here is his report. Irvine is a good observer and an honest man. No editor can hope more. der but at present they have mvself looking at the situation for no voice in the matter. through the eyes of an American. The man who was described My sympathies were with the to Home Rule movement and what I me by Sir Horace Plunkett as "the greatest living Irishman" is saw confirmed my the sympathies in that direction. I had some ideas poet and dreamer George W. Russell ("A. He is about violence as E."). against the a political weapon and they were strengthened in policy of violence, so is Sir Horace. -

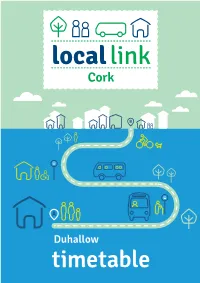

Duhallow Timetables

Cork B A Duhallow Contents For more information Route Page Route Page Rockchapel to Mallow 2 Mallow to Kilbrin 2 Rockchapel to Kanturk For online information please visit: locallinkcork.ie 3 Barraduff to Banteer 3 Donoughmore to Banteer 4 Call Bantry: 027 52727 / Main Office: 025 51454 Ballyclough to Banteer 4 Email us at: [email protected] Rockchapel to Banteer 4 Mallow to Banteer 5 Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Rockchapel to Cork 5 Kilbrin to Mallow 6 Operated By: Stuake to Mallow 6 Local Link Cork Local Link Cork Rockchapel to Kanturk 6 Council Offices 5 Main Street Guiney’s Bridge to Mallow 7 Courthouse Road Bantry Rockchapel to Tralee 7 Fermoy Co. Cork Co. Cork Castlemagner to Kanturk 8 Clonbanin to Millstreet 8 Fares: Clonbanin to Kanturk 8 Single: Return: Laharn to Mallow 9 from €1 to €10 from €2 to €17 Nadd to Kanturk 9 Rockchapel to Newmarket 10 Freemount to Kanturk 10 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Rockchapel to Rockchapel Village 10 Rockchapel to Young at Heart 11 Contact the office to find out more about our wheelchair accessible services Boherbue to Castleisland 11 Boherbue to Tralee 12 Rockchapel to Newmarket 13 Taur to Boherbue 13 Local Link Cork Timetable 1 Timetable 025 51454 Rockchapel-Boherbue-Newmarket-Kanturk to Mallow Rockchapel-Ballydesmond-Kiskeam to Kanturk Day: Monday - Friday (September to May only) Day: Tuesday ROCKCHAPEL TO MALLOW ROCKCHAPEL TO KANTURK Stops Departs Return Stops Departs Return Rockchapel (RCC) 07:35 17:05 Rockchapel (RCC) 09:30 14:10 -

Rural Housing

County Development Plan Review Rural Housing Background Paper November 2012 Planning Policy Unit Cork County Council Rural Housing Background Paper November 2012 ii Rural Housing Background Paper November 2012 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ii 1. Introduction 1 2. Rural Population Change 2006 – 2011 3 3. Recent Patterns of Rural Housing Development 7 4. Environmental Sensitivity and Rural Housing Pressure 25 5. Defining Areas of Strong Urban Influence 27 6. Identification of Rural Area Types 31 7. Conclusions 37 Note: Although November 2012 is the cover date on this document the data used to inform the document was largely collected in late 2011 and throughout 2012. i Rural Housing Background Paper November 2012 Executive Summary i. Terms of Reference The main outputs of this study are to: (a) Review policies for the Metropolitan Greenbelt and Rural Housing Control Zone and (b) A review of the rural housing policies applicable to the remainder of the County, based on the template put forward in the Sustainable Rural Housing Guidelines 2005. It was agreed at the Planning Policy Group Meeting of the 17th January 2012 that although the initial aim of this study is to review the rural housing policies for the Metropolitan Greenbelt, this needs to be carried out in line with the overall approach to rural housing set out in the Ministerial Guidelines. The following section outlined the agreed approach for the study which was adapted to address any emerging issues as the study progressed. The Approach of this Study is to: • Use the Sustainable Rural Housing Guidelines as a template to revise and review the current rural housing policy. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

2019 Clan Gathering Itinerary

2019 CLAN GATHERING ITINERARY Friday 13th September 16:00 PROMPTLY COACH DEPARTS FROM ROCHESTOWN HOTEL TO CASTLE HOTEL IN MACROOM WITH CROWLEYS RESIDING THERE. If ROCHESTOWN residents wish, they may drive themselves to Macroom and take the coach back, leaving their cars at the Castle Hotel 14:00 - 18:00 Registration at Castle Hotel in Macroom Note: FOOD ON YOUR OWN AT CASTLE HOTEL IS AVAILABLE ALL EVENING. 18:00 - 20:00 Cheese and Wine Reception at Castle Hotel followed by welcoming Ceremony 20:00 – 22:00 Castle Hotel with Dick Beamish, Guest entertainer followed by Irish Dancing Demonstration, concluding with an evening of Irish music by our own Larry Crowley and Kevin. COACH WILL RETURN TO ROCHESTOWN HOTEL ABOUT 12:30 AM IRISH TIME!! Saturday 14th September 9:00 PROMPTLY COACH DEPARTS FROM ROCHESTOWN HOTEL TO CASTLE HOTEL IN MACROOM WITH CROWLEYS RESIDING THERE. 9:30 - 10:30 Business Meeting and Website Information Meeting at CASTLE HOTEL 11:00 Departing on Buses from CASTLE HOTEL FOR TOURING. 11:30 Stop off at Kilmichael Ambush. Address by Local Historian. The Kilmichael Ambush was an ambush near the village of Kilmichael in County Cork on 28 November 1920 carried out by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence. Thirty-six local IRA volunteers commanded by Tom Barry killed seventeen members of the Royal Irish Constabulary's Auxiliary Division. The Kilmichael ambush was politically as well as militarily significant. It occurred one week after Bloody Sunday, marking an escalation in the IRA's campaign. 12:30 - 13:30 Visit to Barrett’s Bar in Coppeen for Drinks and Sandwiches 14:30 Mass at O’ Crowley Castle 16:30 Returning to CASTLE AND ROCHESTOWN HOTELS. -

Whats on CORK

Festivals CORK CITY & COUNTY 2019 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE January 5 to 18 Mental Health First Fortnight Various Venues Cork City & County www.firstfortnight.ie January 11 to 13 Chess Mulcahy Memorial Chess Metropole Hotel Cork Congress www.corkchess.com January 12 to 13 Tattoo Winter Tattoo Bash Midleton Park Hotel www.midletontattooshow.ie January 23 to 27 Music The White Horse Winter The White Horse Ballincollig Music Festival www.whitehorse.ie January TBC Bluegrass Heart & Home, Old Time, Ballydehob Good Time & Bluegrass www.ballydehob.ie January TBC Blues Murphy’s January Blues Various Locations Cork City Festival www.soberlane.com Jan/Feb 27 Jan Theatre Blackwater Valley Fit Up The Mall Arts Centre Youghal 3,10,17 Feb Theatre Festival www.themallartscentre.com Jan/Feb 28 to Feb 3 Burgers Cork Burger Festival Various Venues Cork City & County www.festivalscork.com/cork- burger-festival Jan/Feb 31 to Feb 2 Brewing Cask Ales & Strange Franciscan Well North Mall Brew Festival www.franciscanwell.com February 8 to 10 Arts Quarter Block Party North & South Main St Cork www.makeshiftensemble.com February TBC Traditional Music UCC TadSoc Tradfest Various Venues www.tradsoc.com February TBC Games Clonakilty International Clonakilty Games Festival www.clonakiltygamesfestival.co m February Poetry Cork International Poetry Various Venues Festival www.corkpoetryfest.net Disclaimer: The events listed are subject to change please contact the venue for further details | PAGE 1 OF 11 DATE CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE Feb/Mar -

June 2020 €2.50 W Flowers for All Occasions W Individually W

THE CHURCH OF IRELAND United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE Technology enables us ‘to be together while apart’ - Rev Kingsley Sutton celebrates his 50th birthday with some of his colleagues on Zoom June 2020 €2.50 w flowers for all occasions w Individually w . e Designed Bouquets l e g a & Arrangements n c e f lo Callsave: ri st 1850 369369 s. co m The European Federation of Interior Landscape Groups •Fresh & w w Artificial Plant Displays w .f lo •Offices • Hotels ra ld •Restaurants • Showrooms e c o r lt •Maintenance Service d . c •Purchase or Rental terms o m Tel: (021) 429 2944 bringing interiors alive 16556 DOUGLAS ROAD, CORK United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE June 2020 Volume XLV - No.6 The Bishop writes… Dear Friends, Another month has passed and with it have come more changes, challenges and tragedies. On behalf of us all I extend sympathy, not only to the loved ones of all those who have died of COVID-19, but also to everyone who has been bereaved during this pandemic. Not being able to give loved ones the funeral we would really want to give them is one of the most heart-breaking aspects of the current times. Much in my prayers and yours, have been those who are ill with COVID-19 and all others whose other illnesses have been compounded by the strictures of these times. In a different way, Leaving Certificate students and their families have been much in my thoughts and prayers. -

WODEHOUSE, Brigadier Edmond

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. A CONCISE BIOGRAPHY OF: BRIGADIER E. WODEHOUSE A short biography of Brigadier E. WODEHOUSE, C.B.E., who served in the British Army between 1913 and 1949. He served in the First World War, being wounded and taken prisoner. During the war, WODEHOUSE served with his Regiment rising to command a Battalion. During the Second World War, he became the Military Attaché to Eire, a sensitive role during ‘The Emergency’. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 16 October 2020 [BRIGADIER E. WODEHOUSE] A Concise Biography of Brigadier E. WODEHOUSE. Version: 3_2 This edition dated: 16 October 2020 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author) Assisted by: Stephen HEAL Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk 1 16 October 2020 [BRIGADIER E. WODEHOUSE] Contents Pages Introduction 3 Early Life 3 First World War 4 – 5 Second World War 5 – 8 Republic of Ireland (Eire) 8 – 13 Military Attaché in Ireland 13 – 16 Retirement and Death 16 – 17 Bibliography and Sources 18 2 16 October 2020 [BRIGADIER E. WODEHOUSE] Brigadier Edmond WODEHOUSE, C.B.E. Introduction Not all Army officers can enjoy careers that leave a legacy which is well known to the public or historians. The majority will lead satisfying, and in their own way, important careers, but these will remain unknown to all but their families and a few historians. -

BMH.WS1234.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,234 Witness Jack Hennessy, Knockaneady Cottage, Ballineen, Co. Cork. Identity. Adjutant Ballineen Company Irish Vol's. Co. Cork; Section Leader Brigade Column. Subject. Irish Volunteers, Ballineen, Co. Cork, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2532 Form BSM2 STATEMENT BY JOHN HENNESSY, Ballineen, Co. Cork. I joined the Irish Volunteers at Kilmurry under Company Captain Patrick O'Leary in 1917. I remained with that company until 1918 when I moved to Ballineen, where I joined the local company under Company Captain Timothy Francis. Warren. Shortly after joining the company I was appointed Company Adjutant. During 1918 and the early days of 1919 the company was. being trained and in 1918 we had preparations made. to resist conscription. I attended meetings of the Battalion Council (Dunmanway Battalion) along with the Company Captain. The Battalion Council discussed the organisation and training in each company area. In May, 1919, the Ballineen Company destroyed Kenniegh R.I.C. barracks. which had been vacated by the garrison.. Orders were issued by the brigade through each battalion that the local R.I.C. garrison was to be boycotted by all persons in the area. This order applied to traders, who were requested to stop supplying the R.I.C. All the traders obeyed the order, with the exception of one firm, Alfred Cotters, Ballineen, who continued to supply the R.I.C. with bread. The whole family were anti-Irish and the R.I.C. -

Planning Applications

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS INVALID APPLICATIONS FROM 10/03/2018 TO 16/03/2018 that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE INVALID DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION 18/00101 Benedict Bannister Permission 14/03/2018 De molition of existing Studio of area c.23 sq.m., alterations including new windows and doors and new slated roof, and new Conservatory extension of area c. 12 sq.m, all to existing detached 3 bedroom bungalow of area c.100 sq.m. and for construction of a new detached 2 storey 3 bedroom house of area c.269 sq.m. with associated site works and landscaping, all on a site of area 0.3251 hA Rushanes Townland Glandore Co Cork 18/00103 Richard Ashen, Madeline McKeown Permission for 14/03/2018 Retention of detached domestic garage ancillary in use to main Retention dwelling house Caher Kilcrohane Bantry Co Cork 18/04474 Sinead Considine Outline Permission 13/03/2018 Construct a single storey dwelling, a garage for domestic use, a proprietary waste water treatment unit with percolation area and bored well. Garranereagh Kilbrittain Co. Cork 18/04476 Ger Cahill Permission 13/03/2018 Dwellinghouse, detached domestic garage with associated site Create date and time: 26/03/2018 09:43:19 CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 2 works Bridestown Kildinan Co. -

Sea Environmental Report the Three

SEA ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT FOR THE THREE PENINSULAS WEST CORK AND KERRY DRAFT VISITOR EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT PLAN for: Fáilte Ireland 88-95 Amiens Street Dublin 1 by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper Dublin 7 AUGUST 2020 SEA Environmental Report for The Three Peninsulas West Cork and Kerry Draft Visitor Experience Development Plan Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................v Glossary ..................................................................................................................vii SEA Introduction and Background ..................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Terms of Reference ........................................................................... 1 1.2 SEA Definition ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 SEA Directive and its transposition into Irish Law .......................................................... 1 1.4 Implications for the Plan ............................................................................................. 1 The Draft Plan .................................................................................... 3 2.1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship with other relevant Plans and Programmes ................................................ 4 SEA Methodology ..............................................................................