Maritime Commerce Strategic Outlook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

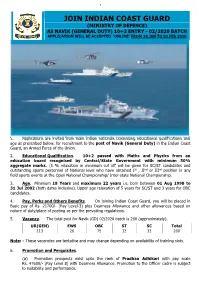

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

Urban Megaprojects-Based Approach in Urban Planning: from Isolated Objects to Shaping the City the Case of Dubai

Université de Liège Faculty of Applied Sciences Urban Megaprojects-based Approach in Urban Planning: From Isolated Objects to Shaping the City The Case of Dubai PHD Thesis Dissertation Presented by Oula AOUN Submission Date: March 2016 Thesis Director: Jacques TELLER, Professor, Université de Liège Jury: Mario COOLS, Professor, Université de Liège Bernard DECLEVE, Professor, Université Catholique de Louvain Robert SALIBA, Professor, American University of Beirut Eric VERDEIL, Researcher, Université Paris-Est CNRS Kevin WARD, Professor, University of Manchester ii To Henry iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My acknowledgments go first to Professor Jacques Teller, for his support and guidance. I was very lucky during these years to have you as a thesis director. Your assistance was very enlightening and is greatly appreciated. Thank you for your daily comments and help, and most of all thank you for your friendship, and your support to my little family. I would like also to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr Eric Verdeil and Professor Bernard Declève, for guiding me during these last four years. Thank you for taking so much interest in my research work, for your encouragement and valuable comments, and thank you as well for all the travel you undertook for those committee meetings. This research owes a lot to Université de Liège, and the Non-Fria grant that I was very lucky to have. Without this funding, this research work, and my trips to UAE, would not have been possible. My acknowledgments go also to Université de Liège for funding several travels giving me the chance to participate in many international seminars and conferences. -

How Best to Respond? Expert Meeting Djibuti, 8-10 November 2011

RefugeesRefugees andand asylumasylum--seekersseekers inin distressdistress atat seasea –– howhow bestbest toto respondrespond?? ExpertExpert meetingmeeting DjibutiDjibuti,, 88--1010 NovemberNovember 20112011 AUTHORITIES INVOLVED IN RESCUE AT SEA Central Directorate Strategic Coordination Navy Navy CoCoastast Guard Operational guidance in high seas Operational guidance for S.A.R. events Guardia di Finanza Police & Carabinieri Operational guidance in territorial waters Close shore line patrolling PrincipalPrincipal FlowsFlows towardstowards ItalyItaly From TUNISIA EGADI ISLANDS TUNISI TUNISIA LINOSA LAMPEDUSA SOUSSE MADIJA * Up to 5 November DATA ON LANDINGS YEARS LANDINGS MEN WOMEN MINOR TOTAL 2009 39 391 1 7 399 2010 51 560 2 52 614 2011* 512 26.682 235 1.102 28.019** **Landing in Lampedusa 25.714 Landing in Linosa 429 In 2011 have been arrested 73 smugglers and facilitators and 337 boats have been confiscated. In the 2010, were arrested only 7 persons and 19 boats were confiscated. Modus Operandi from Tunisia • By zodiac or wooden boat, of about 4 to 15 meters in length with 3 to 279 persons aboard (on a boat of 12 meters in length) • By fishing boats of 15/25 meters in length (maximum 344 persons aboard a boat of 15 meters in length) • Principally young males • Many trips are self-organized • Nocturnal departure • The cost is about 1,500/2,000 dinars • The Tunisians, generally, claim to want to reach northern Europe From LIBYA SICILY LINOSA LAMPEDUSA TRIPOLI ZUARA MISRATAH LIBYA * Up to 26 may DATA ON LANDINGS YEARS LANDINGS MEN WOMEN MINOR TOTAL 2009 55 4,928 896 466 6,290 2010 9 279 10 57 346 2011* 99 23.137 3.016 1.985 28.318 In 2011 have been arrested 51 smugglers and facilitators and have been confiscated 60 boats. -

Port Security

S. HRG. 107–593 PORT SECURITY HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARING APRIL 4, 2002—SEATTLE, WA Printed for the use of the Committees on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–047 PDF WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 21-JUN-2000 10:09 Oct 23, 2002 Jkt 081047 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\12HEAR\2003\081047.XXX CHERYLM PsN: CHERYLM COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii TED STEVENS, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania TOM HARKIN, Iowa PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri HARRY REID, Nevada MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky HERB KOHL, Wisconsin CONRAD BURNS, Montana PATTY MURRAY, Washington RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JACK REED, Rhode Island MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Minority Deputy Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND RELATED AGENCIES PATTY MURRAY, Washington, Chairman ROBERT C. -

Harbor Management Plan January 2021

Town of Harwich Harbor Management Plan Adopted by the Board of Selectmen: January 26, 2004 Effective Date: February 9, 2004 Amendment Dates: 2004: March 15, April 12, August 16 2005: January 18, March 7, July 5, October 11 2006: March 27, October 30 2007: December 17 2008: January 14, May 19 2009: March 30, September 21, November 23 2011: February 28, September 26, October 24 2012: July 23, October 15 2013: February 19, July 29 2014: January 6, March 10, July 14, December 1 2015: May 18, May 26, August 24 2016: January 4, May 9, November 28 2017: January 9, September 11, December 11 2018: August 6, August 20, December 3 2019: May 28, September 9 2020: March 9 2021: January 4 This document is available in PDF format on the Town of Harwich website: www.harwich-ma.gov Town of Harwich Harbor Management Plan Table of Contents Section Heading Page 1.0 Purpose 2 2.0 Definitions 2 3.0 Mooring and Slip Permits and Regulations 6 4.0 Mooring Tackle and Equipment 10 5.0 Waiting List, Policy and Ownership Limitation 12 6.0 Town-Owned Dockage Refund Policy; Liens; Collections; Interest 13 7.0 Slip Regulations at Town-Owned Marina 13 8.0 Offloading Permits and Regulations at Town-Owned Facilities 15 9.0 Fueling Area Regulations 18 10.0 Speed Zones and Mooring Areas 19 11.0 Wet bikes and Jet Skis 20 12.0 Long Pond - Regulations for Motorboats 20 13.0 Boat Ramps 20 14.0 Wastes/Trash Disposal and Use of Dumpsters 21 15.0 Waterways and Ponds 22 16.0 Emergency Haul Outs 22 17.0 Sport fishing Boats: Tuna Buyer Permits and Regulations (T-Permits) 23 18.0 Hurricane -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Moorage Tariff #6 – Port of Seattle Harbor Island Marina

Port of Seattle Moorage Tariff #6 HIM – 2019.1 Effective January 1, 2019 MOORAGE TARIFF #6 – PORT OF SEATTLE HARBOR ISLAND MARINA ITEM 1 TITLE PAGE NOTICE: The electronic form of the Moorage Tariff will govern in the event of any conflict with any paper form of the Moorage Tariff. If you have printed an older version of this tariff, you need to print this version in its entirety. NAMING: RATES, CHARGES, RULES AND REGULATIONS APPLYING TO HARBOR ISLAND MARINA ISSUED BY Port of Seattle 2711 Alaskan Way Seattle, Washington 98121 ISSUING AGENT ALTERNATE ISSUING AGENT Stephanie Jones Stebbins Kenneth Lyles Managing Director, Maritime Division Port of Director, Fishing and Commercial Operations Seattle Port of Seattle PO Box 1209 PO Box 1209 Seattle, WA 98111 Seattle, WA 98111 Phone: 206-787-3818 Phone: 206-787-3397 FAX: 206-787-3280 FAX: 206-787-3393 [email protected] [email protected] ALTERNATE ISSUING AGENT Tracy McKendry Sr. Manager, Recreational Boating Port of Seattle PO Box 1209 Seattle, WA 98111 Phone: 206-787-7695 FAX: 206-787-3391 [email protected] Page 2 of 22 QUICK-REFERENCE RATE TABLE * ~ LEASEHOLD TAX IS IN ADDITION TO NAMED RATES ~ MONTHLY MOORAGE RATES - COMMERCIAL Rate per lineal foot is $13.09 MONTHLY MOORAGE RATES – NON-COMMERCIAL Berth Size Rate Per Foot Up to 32 feet $11.03 33 feet to 40 feet $11.27 41 feet and above $11.47 GRANDFATHERED MONTHLY LIVEABOARD FEE $95.00 NEW MONTHLY LIVEABOARD FEE $117.35 Incidental Charter and Guest Moorage Accommodation by Manager Approval Only *For complete rate details, please see ITEM 3100 - RATES Page 3 of 22 Table of Contents ITEM 1 TITLE PAGE .......................................................................................................................1 ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................. -

Submission-Mare-Liberum

1 Submission to the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants by Mare Liberum Mare Liberum is a Berlin based non-profit-association, that monitors the human rights situation in the Aegean Sea with its own ships - mainly of the coast of the Greek island of Lesvos. As independent observers, we conduct research to document and publish our findings about the current situation at the European border. Since March 2020, Mare Liberum has witnessed a dramatic increase in human rights violations in the Aegean, both at sea and on land. Collective expulsions, commonly known as ‘pushbacks’, which are defined under ECHR Protocol N. 4 (Article 4), have been the most common violation we have witnessed in 2020. From March 2020 until the end of December 2020 alone, we counted 321 pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, in which 9,798 people were pushed back. Pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard and other European actors, as well as pullbacks by the Turkish Coast Guard are not a new phenomenon in the Aegean Sea. However, the numbers were significantly lower and it was standard procedure for the Hellenic Coast Guard to rescue boats in distress and bring them to land where they would register as asylum seekers. End of February 2020 the political situation changed dramatically when Erdogan decided to open the borders and to terminate the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 as a political move to create pressure on the EU. Instead of preventing refugees from crossing the Aegean – as it was agreed upon in the widely criticised EU-Turkey deal - reports suggested that people on the move were forced towards the land and sea borders by Turkish authorities to provoke a large number of crossings. -

Post 9/11 Maritime Security Measures : Global Maritime Security Versus Facilitation of Global Maritime Trade Norhasliza Mat Salleh World Maritime University

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2006 Post 9/11 maritime security measures : global maritime security versus facilitation of global maritime trade Norhasliza Mat Salleh World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mat Salleh, Norhasliza, "Post 9/11 maritime security measures : global maritime security versus facilitation of global maritime trade" (2006). World Maritime University Dissertations. 98. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/98 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden POST 9/11 MARITIME SECURITY MEASURES: Global Maritime Security versus the Facilitation of Global Maritime Trade By NORHASLIZA MAT SALLEH Malaysia A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE in MARITIME AFFAIRS (MARITIME ADMINISTRATION) 2006 © Copyright Norhasliza MAT SALLEH, 2006 DECLARATION I certify that all material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The content of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. Signature : …………………………… Date : ……………………………. Supervised by: Cdr. -

GAO-21-539, COVID-19: the Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Addressees July 2021 COVID-19 The Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges, but Could Improve Telework Documentation and Personnel Data GAO-21-539 July 2021 COVID-19 The Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges, but Could Improve Telework Documentation and Highlights of GAO-21-539, a report to Personnel Data congressional addressees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The Coast Guard is a multi-mission The U.S. Coast Guard took steps to safeguard its personnel during the COVID- maritime military service responsible 19 pandemic by updating its policies and guidance, expanding telework, and for maritime safety, security, and administering COVID-19 vaccines, among other efforts. For example, the Coast environmental protection, among other Guard formed a COVID-19 Crisis Action Team comprising targeted working things. During the pandemic, the Coast groups to address COVID-19-related issues and develop new policies and Guard has faced challenges in guidance. Further, from December 2020 through April 2021, the Coast Guard balancing the need to safeguard its administered vaccines to 35,439 (about 64 percent) of its personnel. personnel with its responsibility to continue missions and operations. Selected U.S. Coast Guard COVID-19 Crisis Action Team Working Groups In response to a CARES Act mandate and congressional requests, GAO reviewed the Coast Guard’s efforts to respond to the pandemic. This report examines (1) the Coast Guard’s actions to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure for its personnel; (2) challenges the Coast Guard faced in operating in a pandemic environment and how it addressed them; and (3) the extent to which the Coast Guard has The Coast Guard also took actions to address a variety of challenges posed by collected and maintained valid and the COVID-19 pandemic. -

“Maritime Transport in Africa: Challenges, Opportunities, and an Agenda for Future Research”

UNCTAD Ad Hoc Expert Meeting (Under the framework of the IAME Conference 2018) 11 September 2018, Mombasa, Kenya “Maritime Transport In Africa: Challenges, Opportunities, and an Agenda for Future Research” Opportunity and Growth Diagnostic of Maritime Transportation in the Eastern and Southern Africa By Professor Godius Kahyarara Economics Department With Assistantship of Debora Simon Geography Department University of Dar-es-Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania This expert paper is reproduced by the UNCTAD secretariat in the form and language in which it has been received. Page 1 The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD. OPPORTUNITY AND GROWTH DIAGNOSTIC OF MARITIME TRANSPORTATION IN THE EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA Professor Godius Kahyarara University of Dar-es-Salaam Economics Department With Assistantship of Debora Simon University of Dar-es-Salaam Geography Department SUMMARY This paper examines opportunities and undertakes growth diagnostics of maritime transportation in the Eastern and Southern Africa. To do so it adopts a ‘Growth Diagnostic ‘methodology proposed by Ricardo Hausman, Dani Rodrick and Andres Velasco (HRV) to identify constraints that impede development of the Maritime transport focusing on a wide range of aspects within transportation corridors that are most critical and binding constraints to development of maritime transportation. The paper also assesses existing opportunities for Maritime Transportation and proposes the best approach to rip such opportunities. Paper findings are that port inefficiency depicted by longer container dwell time, delays in vessel traffic clearance, lengthy documentation processing, lesser container per crane hour (with exception of South Africa) as one of the critical binding constraints.