From Evidence to Opportunity: State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shimna Flood Alleviation Scheme

Shimna River Flood Alleviation Scheme Environmental Statement – Non-Technical Summary Department for Infrastructure (DfI) Rivers August 2018 49 Tullywiggan Road Loughry Cookstown BT80 8SG Shimna River Flood Alleviation Scheme Environmental Statement – Non-Techncial Summary 1. Introduction The Environmental Statement (ES) is a detailed report of the findings of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. In particular, it predicts the environmental effects that the Proposed Scheme would have, and details the measures proposed to reduce or eliminate those effects. It is a statement that includes such of the information referred to in Schedule 2A to the Drainage Order 1973, as substituted by The Drainage (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2017, that is reasonably required to assess the environmental effects of any proposed drainage works and which the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) - Rivers can, having regard in particular to current knowledge and methods of assessment, reasonably be required to compile. This shall include a Non-Technical Summary (NTS) of the information provided under points 1 to 9 below: 1. a description of the Proposed Scheme; 2. a description of the reasonable alternatives studied by the Department; 3. a description of the relevant aspects of the current state of the environment, including the ‘Do- Nothing’ scenario. 4. a description of the factors likely to be significantly affected by the Proposed Scheme; 5. a description of the likely significant effects of the works on the environment 6. a description of whether the likely significant effects would be direct and indirect, secondary, cumulative, transboundary, short, medium and long-term, permanent and temporary, positive and negative; 7. -

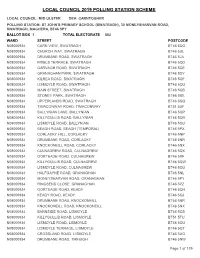

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER POLLING STATION: ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 882 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QG N08000934CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH BT46 5UL N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5JA N08000934FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH BT46 5QD N08000934GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QE N08000934GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5DY N08000934KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QF N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH BT46 5QB N08000934STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5BE N08000934UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QQ N08000934TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY BT51 5UF N08000934BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QP N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QR N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QU N08000934BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL) BT46 5PX N08000934CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY BT46 5NP N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NX N08000934CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QX N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5RF N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QW N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QU N08000934HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5NL N08000934MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PY N08000934RINGSEND CLOSE, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PZ N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QH N08000934KEADY ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QJ N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NX N08000934BARNSIDE ROAD, LISMOYLE -

And Brown Trout (Salmo Trutta L.)

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title The study of molecular variation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) and brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) Author(s) O'Toole, Ciar Publication date 2014 Original citation O'Toole, Ciar. 2014. The study of molecular variation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) and brown trout (Salmo trutta L.). PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2014, Ciar O'Toole. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1932 from Downloaded on 2021-09-23T17:31:56Z The study of molecular variation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) and brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) Ciar O’Toole, B.Sc. (Hons.), M.Sc. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research supervisors: Professor Tom Cross, Dr. Philip McGinnity Head of School: Professor John O’Halloran School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences National University of Ireland, Cork January 2014 Table of Contents Declaration ................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... 2 General Abstract........................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1: General Introduction ............................................................................. -

Reference Number Location Proposal Application Status Date Decision

Reference Number Location Proposal Application Date Decision Status Issued LA09/2015/0407/PAN Lands to the rear of 45 Cornamaddy Develop lands for quarry operations PROPOSAL OF 16/10/2018 Road Pomeroy LA09/2015/1035/LDE Lands approximately 62m West of 15 Retention of shed 4 (as shown on attached PERMITTED DE 08/10/2018 Tobermesson Road Benburb map) Continuation of use for general industrial purposes including assembly, manufacturing , cleaning, processing, treating, fabricating materials with anciliary storage continuation in use of land for purposes of external storage 9of building materials and gas canisters) as shown as area A on attached map LA09/2016/0062/O Adjacent to no.48 Killycon Road Proposed site for farm dwelling PERMISSION G 04/10/2018 Tyanee Portglenone Reference Number Location Proposal Application Date Decision Status Issued LA09/2016/1567/DC Crockandun Discharge of Condition No 20 of Planning CONDITION DIS 05/10/2018 approximately 450m WSW of junction of Approval H/2010/0009/ F Cullion Road and Drumard Road Draperstown Magherafelt LA09/2017/0087/F Lands opposite 54 Ballynasaggart Road Retention of change of use from coal yard PERMISSION G 10/10/2018 Glenchuil Dungannon to outdoor commercial recreational and airsoft club LA09/2017/0387/O Approx 20m North of 33 Oldtown Road Proposed dwelling and domestic PERMISSION G 05/10/2018 Bellaghy garage/store LA09/2017/0458/F Lands adjacent to Annagher Service 3No. retail units to replace existing PERMISSION G 18/10/2018 Station dwelling and associated site works 137 Annagher Road -

Tollymore Forest Park by C

Tollymore Park 53 than no::mal trapping methods and that when replanting of felled coniferous are:!.s is carried out immediately after clear-fellmg, the dIp ping of the transplants in Didimac solution, prior to planting, is to be recommended wherever pine weevil damage IS antIcipated. Tollymore Forest Park By c. S. KILPATRICK N 1953 the new Porestry Act passed by the Government of Norther? I Ireland contained a clause grantmg power to the Mmistry of Agn culture to set up Forest Parks and to proclaim bye-laws for their regu lation. The objects of such parks are to encourage the public to take an added interest in forestry and to offer the enjoyment of an area of great natural beauty to as many people as possible. A forest park therefore must be an attractive forest in beautiful surroundings and either in a major tourist area or close to a large town or city. Tollymore Park was an obvious choice as regards attractiveness and proximity to a city and being in one of the major tourist areas of the province, 30 miles south of Belfast and only 2 miles from the sea-side resert of Newcastle "where the Mountains of Mourne sweep down to the sea. " It was, therefore, declared Northern Ireland's first forest park and was officially opened by the Governor, Lord Wakehurst, before several hundred guests on 2nd June, 1955. The Park, which will be remembered by those members of the Society who visited it in May, 1952, has an area of 1,192 acres and lies in the valley of the Shimna River flowing eastward along the foothills of the Mourne Mountains in a rocky gorge before breaking out to the sea at Newcastle. -

Mourne Seven Sevens 2019 Final Instructions

Mourne Seven Sevens 2019 Final Instructions Phone Number – 07845 659503 Give your Name and Entry Number in all messages In an emergency dial 999 ask for Police then Mountain Rescue Lagan Valley Orienteers welcomes you to the Mourne Seven Sevens Challenge Walk. Please remember that this event is a personal challenge and not a race. To complete this challenge you must be an experienced hill walker and be fit enough for the distance, climb and terrain involved. The exact route is not fixed and is not way-marked at any stage. Navigational skills will be required, especially if weather conditions are poor so participants must have the ability and experience to use both map and compass. (Navigation using only a smartphone app is not allowed). Registration opens on Saturday morning at 06:30 at the north end of the playing field beside Donard car park in Newcastle. The car park is free but parking may be limited due to other events. Please car share if possible and allow time to find parking nearby. You will need to hand in the Registration Form (click here to download ) with details of your car registration, walking companions (if any), contact details, etc. Please print out and complete this in advance so as to save you time queuing on Saturday morning. You will be given a set of green plastic tabs and one small white tab with your entry number on each of them. For convenience they will be held together on a string. You will also receive an electronic timing chip (aka dibber) which will be fastened to your wrist. -

Review of Response to Flooding on 27 and 28 June 2012

Review of Response to Flooding on 27th and 28th June 2012 PEDU September 2012 PEDU Review of Response to Flooding on 27th and 28th June 2012 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Background and Terms of Reference 2. Organisational Context 3. Chronology of the Events of 27th / 28th June 2012 4. Flood Defence: Good Practice Elsewhere 5. Conclusions and Recommendations List of Annexes Annex 1 – Background on Belfast Resilience Forum Annex 2 – Illustration of Flood Alerts England and Wales Annex 3 – Illustration of Flood Alerts Scotland Annex 4 – Met Office Weather Warnings Annex 5 – Claim data taken from 2007 to 2012 - Schemes of Emergency Financial Assistance Annex 6 – Recommendations from Review of the Operational Performance of the Rivers Agency (October Flooding Events) 2011 Annex 7 – Recommendations from Surface Water Flood Management Roles and Responsibilities Report (December 2011) Annex 8 – Recommendations from Action Plan on Freeze Thaw Incident of 2010 Annex 9 – Action Plan 2 PEDU Review of Response to Flooding on 27th and 28th June 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (i) The torrential rain of 27th and 28th of June 2012 was exceptional and the volume and pace of the downpours exceeded the design capacity of local drainage infrastructure. There is no evidence that infrastructure did not perform to expected standards. (ii) Since 2007, only 2010 did not have a serious local flooding incident. Given the frequency of excessive weather episodes it would be prudent to look again at the investment priority allocated to counter flood measures and programmes. (iii) Considering the apparent increase in the incidence of flooding, it seems anomalous that Northern Ireland remains without a flood alert and warning system. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off The Beaten Track: Slieve Binnian *Crown Copyright. Route and Distances are approx. Only for guidance.* Sliabh Binnian - Mountain of the little horns (peaks) Within an elliptical area of about 22km by 11km, The Mourne Mountains are among the most famous tourist attractions and perhaps the most popular walking areas in Northern Ireland. The highest point in Northern Ireland, Slieve Donard and the other 34 summits and forests, loughs, rivers and bogs attract visitors all year round. There is something for everyone here from casual "stroller" to dedicated rambler and runner and our rich heritage is written all over them. The Mountains of Mourne were originally known as Beanna Boirche, after a Celtic chieftain and cowherd called Boirche who ruled his little kingdom from Slieve Binnian, the third highest peak in Northern Ireland after Slieve Donard and Slieve Commedagh. Binnian is called the Mountain of the little horns because of its long summit ridge with several tors (rocky outcrops) that resemble an array of little horns. This route also takes in part of the famous Mourne Wall made from the granite quarried in the Mournes. On average 2m high and 1 metre wide, with virtually no cement to keep it together, it runs for 35km over the tops of 15 mountains and took 18 years between 1904 and 1922 to complete. This walk has been split into two parts. Both can be done in a day but this would require a very early start, ideally between late Spring and early Autumn and a lot of stamina. We opted for one relatively easy walk, an overnight wild camp then the more difficult ascent of Slieve Binnian the next day. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Arva Drumkee 275 Kv Feasibility Study

NIE and ESB National Grid Arva - Drumkee 275kV Feasibility Study ESBI Report No. PE687 -R102 -001 -001 -000.doc Electrical Power Systems, ESBI Engineering Ltd Stephen Court 18/21 St Stephen’s Green Dublin 2 Ireland Telephone+353 -1-703 8000 Fax+3 53 -1-661 6600 www.esbi.ie DATE 04/03/04 File Reference: Falcon/DMS Client: ESB National Grid & Networks Project Title: Arva - Drumkee 275kV Report Title: Arva - Drumkee 275kV Feasibility Study Report No.: PE687-R102-001-001-000.doc Rev. No.: 0 Volume 1 of 1 APPROVED: C.Boylan DATE: 04/0 3/04 TITLE: COPYRIGHT © ESB INTERNATIONAL LIMITED (1998) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, NO PART OF THIS WORK MAY BE MODIFIED OR REPRODUCED OR COPIES IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS - GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, REC ORDING, TAPING OR INFORMATION AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE OTHER THAN ITS DESIGNATED PURPOSE, WITHOUT THE WRITTEN PERMISSION OF ESB INTERNATIONAL LIMITED. ESBI File Re f: PE687-F102 Client: ESB National Grid and Northern Ireland Electricity Project Title: Arva-Drumkee 275kV Line Report Title: Arva-Drumkee 275kV Feasibility Study ESBI Report No.: PE687-R102-001-001-000.doc Rev. No.: 0 Volume 1 of 1 APPROVED: DATE: Cathal Boylan, ESB International 20/02/04 Michael Hewitt, NIE © Northern Ireland Electricity plc All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, photocopying or otherwise outside of Northern Ireland Electricity plc and without the prior permission of Northern Ireland Electricity plc. -

Silent Valley Walking Trails

Interest points NI Water would like to acknowledge its partners in this project. MOUNTAIN TRAIL Silent Valley Dam (Built 1923-1933). This earth filled dam Distance: 3.4km (2 miles) required a cut off trench to prevent water seeping below Silent Valley the dam and moving it. A core wall of “puddle clay” was built Route description: Enjoy the stunning scenery along and the embankment slopes completed with “graded rock this trail which incorporates steep climbs through typical fill”, soil and then grass. Notice the Overflow (7) and Valve Mourne upland habitat and woodland trails. Look out for Mourne Mountains Tower (8) as you pass the corner of the dam wall. the site of Watertown Site (12) and the Pugmill (13). Landscape Partnership Walking Trails Ben Crom Dam (Built 1954-1957). After 5 km (3 miles), climb the 260 steps to the top of the dam wall where you CHALLENGE TRAIL can catch a glimpse of the Brandy Pad and Slieve Donard. Distance: 3km (1.9 miles) Unlike the Silent Valley, Ben Crom is a gravity dam as it depends on its weight for stability. Route description: This scenic trail passes through some steep upland habitat and park woodland. HERITAGE TRAIL Interest points Distance: 2.8 km (1.75 miles) Quarry Viewpoint (10) Cornish workers came here to Route description: Circular route including views over the prospect for silver and lead. Their singing and laughter may dam into the mountains. Find out more about Silent Valley be the reason why the Silent Valley was formerly known as at the Interpretive Centre (3), which was the site of the ‘Happy Valley’. -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1/CN TOTAL ELECTORATE 880 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934 CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QG N08000934 CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5UL N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5JA N08000934 FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QD N08000934 GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QE N08000934 GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5DY N08000934 KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QF N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QU N08000934 MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QB N08000934 STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5BE N08000934 UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QQ N08000934 TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY, KILREA BT51 5UF N08000934 BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QP N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QR N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL), SWATRAGH BT46 5PX N08000934 CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NP N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NR N08000934 KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NX N08000934 CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QX N08000934 GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5RF N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QW N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN, SWATRAGH