Merchants of Marrakesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ambiguous Agreement in a Wastewater Reuse Project in Morocco

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 13 | Issue 2 Ennabih, A. and Mayaux, P.-L. 2020. Depoliticising poor water quality: Ambiguous agreement in a wastewater reuse project in Morocco. Water Alternatives 13(2): 266-285 Depoliticising Poor Water Quality: Ambiguous Agreement in a Wastewater Reuse Project in Morocco Amal Ennabih Sciences-po Lyon, UMR Triangle, Lyon, France; [email protected] Pierre-Louis Mayaux CIRAD, UMR G-EAU, Univ Montpellier, Montpellier, France; [email protected] ABSTRACT: How are depoliticising discourses on water issues produced and rendered effective? Research on discursive depoliticisation has focused on the ability of different types of policy networks to generate powerful and reasonably coherent depoliticised narratives. In the paper, by tracing the depoliticisation of poor water quality in a wastewater reuse project in Marrakesh, Morocco, we suggest that depoliticised discourses can also be produced in a much more dispersed, less coordinated way. In the case analysed here, depoliticisation occurred through an 'ambiguous agreement' around a highly polysemic idea, that of innovation. All the key actors understood that the project was innovative but that water quality was not a significant part of the innovation. This encouraged each actor to frame poor water quality as a strictly private matter that the golf courses needed to tackle on their own; however, each actor also had their own, idiosyncratic interpretation of exactly what this innovation was about and why poor water quality was in the end not that important. Showing how depoliticisation can be the product of mechanisms with varying degrees of coordination helps account for the ubiquity of the phenomenon. -

Marrakech – a City of Cultural Tourism Riikka Moreau, Associate Karen Smith, MRICS, Director Bernard Forster, Director

2005 Marrakech – A city of cultural tourism Riikka Moreau, Associate Karen Smith, MRICS, Director Bernard Forster, Director HVS INTERNATIONAL LONDON 14 Hallam Street London, W1W 6JG +44 20 7878-7738 +44 20 7436-3386 (Fax) September 2005 New York San Francisco Boulder Denver Miami Dallas Chicago Washington, D.C. Weston, CT Phoenix Mt. Lakes, NJ Vancouver Toronto London Madrid New Delhi Singapore Hong Kong Sydney São Paulo Buenos Aires Newport, RI HALFWAY THROUGH THE VISION 2010 PLAN TIME-FRAME – WHAT HAS BEEN ACHIEVED SO FAR AND WHAT OF THE FUTURE? Morocco As has been much documented already, Morocco has immense plans and ambitions to become a tourist destination to enable it to compete effectively alongside other Mediterranean countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece. To briefly recap, the king of Morocco announced in January 2001 that tourism had been identified as a national priority; the government’s ‘Vision 2010’ (or ‘Plan Azur’) strategy embodied this strategy. From the outset the key objectives of Vision 2010 were as follows. To increase tourist numbers to 10 million per annum by 2010; The development of six new coastal resorts; The construction of 80,000 new hotel bedrooms, with two-thirds to be in seaside destinations; 600,000 New jobs to be created in the hotel and tourism industry. Alongside these objectives, which were essentially focused on the mass tourism sector, cities such as Marrakech and Casablanca also set out their own strategies to develop their share of the tourism market. These plans were launched at a time when the world economy was continuing to grow; however, this situation very quickly changed in 2001. -

RABBIS of MOROCCO ~15Th Century to 20Th Century Source: Ben Naim, Yosef

RABBIS OF MOROCCO ~15th Century to 20th Century Source: Ben Naim, Yosef. Malkhei Rabanan. Jerusalem, 5691 (1931) Sh.-Col. Surname Given Name Notes ~ Abbu see also: Ben Abbu ~ ~ .17 - 2 Abecassis Abraham b. Messod Marrakech, Lived in the 6th. 81 - 2 Abecassis Maimon Rabat, 5490: sign. 82 - 3 Abecassis Makhluf Lived in the 5th cent. 85 - 3 Abecassis Messod Lived in the 5th cent., Malkhluf's father. 85 - 2 Abecassis Messod b. Makhluf Azaouia, 5527: sign. , Lived in the 5-6th cent., Abraham's father. 126 - 3 Abecassis Shimon Mogador, Lived in the 7th cent. 53 - 2 Abecassis Yehuda Mogador, 5609: sign. 63 - 1 Abecassis Yihye 5471: sign. 61 - 4 Abecassis Yosef Rabat, 5490: sign. 54 - 1 Aben Abbas Yehuda b. Shmuel Fes, born 4840, had a son Shmuel, moved to Aleppo,Syria.D1678 .16 - 4 Aben Danan Abraham Fes, 5508: sign. .17 - 1 Aben Danan Abraham b. Menashe Fes, born :13 Kislev 5556, d. 12 Adar 5593 .16 - 4 Aben Danan Abraham b. Shaul Fes, d.: 5317 39 - 3 Aben Danan Haim (the old) Fes, lived in the end of the 6th cent. & beg. 7th. 3 sons: Moshe. Eliahu, Shmuel. 82 - 1 Aben Danan Maimon b. Saadia Fes, Brother of the Shmuel the old, 5384: sign. 82 - 1 Aben Danan Maimon b. Shmuel Castilla, expulsed, moved to Fes, 5286: killed. 84 - 2 Aben Danan Menashe I b. Abraham Fes, d.: 5527 (very old) 84 - 3 Aben Danan Menashe II b. Shmuel Fes, lived in the 6th cent. 85 - 4 Aben Danan Messod b. Yaakov Fes, lived in the end of 5th cent. -

JGI V. 14, N. 2

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 14 Number 2 Multicultural Morocco Article 1 11-15-2019 Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation (2019) "Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Morocco JOURNAL of GLOBAL INITIATIVES POLICY, PEDAGOGY, PERSPECTIVE 2019 VOLUME 14 NUMBER 2 Journal of global Initiatives Vol. 14, No. 2, 2019, pp.1-28. The Year of Morocco: An Introduction Dan Paracka Marking the 35th anniversary of Kennesaw State University’s award-winning Annual Country Study Program, the 2018-19 academic year focused on Morocco and consisted of 22 distinct educational events, with over 1,700 people in attendance. It also featured an interdisciplinary team-taught Year of Morocco (YoM) course that included a study abroad experience to Morocco (March 28-April 7, 2019), an academic conference on “Gender, Identity, and Youth Empowerment in Morocco” (March 15-16, 2019), and this dedicated special issue of the Journal of Global Initiatives. Most events were organized through six different College Spotlights titled: The Taste of Morocco; Experiencing Moroccan Visual Arts; Multiple Literacies in Morocco; Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development Challenges in Morocco, Moroccan Cultural Festival; and Moroccan Solar Tree. -

The Historic City of Meknes

WORLD HERITACE LIST Meknes No 793 Identification Nomination The Historie City of Meknes Location Wilaya of Meknes State Party Kingdom of Morocco Date 26 October 1995 Justification by State Party The historie city of Meknes has exerted a considerable influence on the development of civil and militarv architecture <the kas/Jan> and works of art. lt also contains the remains of the royal city founded by Sultan Moulay 1smaïl <1672-1727>. The presence of these rare remains within an historie town that is in turn located within a rapidly changing urban environ ment gives Meknes its universal value. Note The State Party does not make any proposais concerning the criteria under which the property sMuid be inscribed on the world Heritage List in the nomination dossier. category of propertv ln terms of the categories of propertv set out ln Article 1 of the 1972 world Heritage convention, the historie city of Meknes is a group of buildings. Historv and Description History The na me of Meknes goes back to the Meknassa, the great Berber tribe that dominated eastern Mo rocco to as far as the Tafililet and which produced Moulay ldriss 1, founder of the Moroccan state and the ldrissid dynasty in the 8th centurv AD. The Almoravid rulers <1053-1147> made a practice of building strongholds for storing food and arms for their troops; this was introduced by Youssef Ben Tachafine, the founder of Marrakech. Meknes was established in this period, at first bearing the name Tagrart <= garrison>. The earliest part to be settled was around the Nejjarine mosque, an Almoravid foundation. -

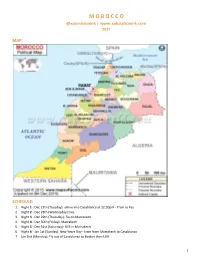

M O R O C C O @Xplorationink | 2017

M O R O C C O @xplorationink | www.xplorationink.com 2017 MAP: SCHEDULE: 1. Night 1 - Dec 27th (Tuesday): arrive into Casablanca at 12:20pm - Train to Fes 2. Night 2 - Dec 28th (Wednesday): Fes 3. Night 3 - Dec 29th (Thursday): Fes to Marrakech 4. Night 4 - Dec 30th (Friday): Marrakech 5. Night 5 - Dec 31st (Saturday): NYE in Marrakech 6. Night 6 - Jan 1st (Sunday): New Years Day - train from Marrakech to Casablanca 7. Jan 2nd (Monday): Fly out of Casablanca to Boston then LAX 1 HOTELS: FES checkin 12.27 (Tuesday) checkout 12.29 (Thursday) Algila Fes Hotel: 1-2-3/17, Akibat Sbaa Douh Fes, 30110 MA MARRAKESH checkin 12.29 (Thursday) checkout 12.30 (Friday) Riad Le Jardin d’Abdou: ⅔ derb Makina Arset bel Baraka, Marrakech, 40000 MARRAKESH checkin 12.31 (Saturday) checkout 01.01 (Sunday) Riad Yasmine Hotel: 209 Diour Saboun - Bab Taghzout, Medina, Marrakech, 40000 CASABLANCA checkin 01.01 (Sunday) checkout 01.02 (Monday) 10 miles from CMN airport Club Val D Anfa Hotel: Angle Bd de l’Ocean Atlantique &, Casablanc, 20180 ADDITIONAL NOTES: 1. Rabat to Fes: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 2. Casablanca to Marrakesh: ~3 hours by bus/train ~$10 3. Casablanca to Rabat: ~1 hour by train ~$5 4. Fes to Chefchaouen (blue town): 3 hours 20 minutes by car 5. No Grand Taxis (for long trips. Take the bus or train) 6. Camel 2 day/1night in Sahara Desert: https://www.viator.com/tours/Marrakech/Overnight-Desert-Trip-from-Marrakech-with-Camel-Ride/d5408-8248P5 7. 1 USD = 10 Dirhams. -

Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization

No. 31874 Multilateral Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organ ization (with final act, annexes and protocol). Concluded at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994 Authentic texts: English, French and Spanish. Registered by the Director-General of the World Trade Organization, acting on behalf of the Parties, on 1 June 1995. Multilat ral Accord de Marrakech instituant l©Organisation mondiale du commerce (avec acte final, annexes et protocole). Conclu Marrakech le 15 avril 1994 Textes authentiques : anglais, français et espagnol. Enregistré par le Directeur général de l'Organisation mondiale du com merce, agissant au nom des Parties, le 1er juin 1995. Vol. 1867, 1-31874 4_________United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités 1995 Table of contents Table des matières Indice [Volume 1867] FINAL ACT EMBODYING THE RESULTS OF THE URUGUAY ROUND OF MULTILATERAL TRADE NEGOTIATIONS ACTE FINAL REPRENANT LES RESULTATS DES NEGOCIATIONS COMMERCIALES MULTILATERALES DU CYCLE D©URUGUAY ACTA FINAL EN QUE SE INCORPOR N LOS RESULTADOS DE LA RONDA URUGUAY DE NEGOCIACIONES COMERCIALES MULTILATERALES SIGNATURES - SIGNATURES - FIRMAS MINISTERIAL DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS AND UNDERSTANDING DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS ET MEMORANDUM D©ACCORD MINISTERIELS DECISIONES, DECLARACIONES Y ENTEND MIENTO MINISTERIALES MARRAKESH AGREEMENT ESTABLISHING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION ACCORD DE MARRAKECH INSTITUANT L©ORGANISATION MONDIALE DU COMMERCE ACUERDO DE MARRAKECH POR EL QUE SE ESTABLECE LA ORGANIZACI N MUND1AL DEL COMERCIO ANNEX 1 ANNEXE 1 ANEXO 1 ANNEX -

A Berber in Agadir: Exploring the Urban/Rural Shift in Amazigh Identity Thiago Lima SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 A Berber in Agadir: Exploring the Urban/Rural Shift in Amazigh Identity Thiago Lima SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Lima, Thiago, "A Berber in Agadir: Exploring the Urban/Rural Shift in Amazigh Identity" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1117. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1117 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lima 1 Thiago Lima 11 December, 2011 SIT Morocco: Migration and Transnational Identity Academic Director: Dr. Souad Eddouda Advisor: Dr. Abderrahim Anbi A Berber in Agadir : Exploring the Urban/Rural Shift in Amazigh Identity Lima 2 Table of Contents Introduction... 3 Methodology: Methods and Limits... 6 Interviews in Agadir... 8 Interviews in Al Hoceima... 14 Interview with Amazigh Cultural Association of America... 18 Analysis... 22 Conclusion... 27 Bibliography... 29 Lima 3 Introduction: The Arab Spring has seen North African and Middle Eastern youth organizing against the status quo and challenging what they perceive as political, economic, and social injustices. In Morocco, while the Arab Spring may not have been as substantial as in neighboring countries, demonstrations are still occurring nearly everyday in major cities like Rabat as individuals protest issues including government transparency, high unemployment, and, for specific interest of this paper, the marginalization of the Amazigh people. -

AND Morocco Cruising the Canary Islands

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Cruising THE Canary Islands AND Morocco Canary Islands Teide San Cristóbal National de la Laguna Park Santa Cruz Santa Cruz La Palma Island Tenerife Island SPAIN Las Palmas Los Cristianos Gran Canaria Island Tenerife Island Kenitra Casablanca Fez UNESCO World Rabat Heritage Site Atlantic Safi Cruise Itinerary Ocean Air Routing Marrakesh Land Routing Canary Islands MOROCCO April 18 to 26, 2022 La Palma u Tenerife Join us on this nine-day itinerary which combines Marrakesh u Casablanca u Fez the natural beauty of the Canary Islands and the 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada Moorish treasures of the rose-pink cities of Morocco. 2 Arrive Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Cruise for seven nights aboard the exclusively chartered, Spain/Embark Le Dumont-d'Urville Five-Star Le Dumont-d’Urville—featuring only 3 Santa Cruz, La Palma 92 Suites and Staterooms, each with a private balcony. 4 Los Cristianos, Santa Cruz, Tenerife Visit La Palma’s scenic Mirador de la Concepción 5 Cruising the Atlantic Ocean for spectacular views of Caldera de Taburiente and 6 Safi, Morocco, for Marrakesh “the beautiful island.” Discover iconic Casablanca. 7 Casablanca Visit four UNESCO World Heritage sites, the stunning 8 Kenitra for Fez island of Tenerife, the 1,000-year-old city of 9 Casablanca/Disembark ship/ Marrakesh and the ancient city of Fez. Las Palmas Return to the U.S. or Canada Pre-Program and Casablanca Post-Program Options. Itinerary is subject to change. Exclusively Chartered Five-Star Small Ship Le Dumont-d’Urville Cruising the Canary Islands and Morocco Included Features* reserve early! Approximate Early Booking pricing from $4995 per person double occupancy for land/cruise program. -

Essential Marrakesh: Marrakesh

Download this itinerary or share it with your clients via email. 5 Days/4 Nights Departs Daily Essential Marrakesh: Marrakesh With its proximity to major European countries like Spain and Portugal, the desert Kingdom of Morocco presents a fantastic opportunity to experience the stark and fascinating contrasts between Africa and Europe. Moroccan cities are exotic and vibrant; each of them offering a unique cornucopia of sensory delights. This select itinerary lets you explore western Morocco's former imperial city - Marrakesh. If Casablanca effortlessly wears its French influence on its sleeves, Marrakesh is a living and breathing remnant of Morocco's medieval past. The 'Red City' is home to a rich artisan heritage, marvelous Moorish architecture, and bustling souks packed inside the labyrinthine cobblestoned lanes of the world-famous Medina. If you only have a short time to visit Morocco, or if it's your first chance to explore this amazing country, then Marrakesh is the perfect place to start your adventure. ACCOMMODATIONS • 4 Nights Marrakesh INCLUSIONS • Private Hidden Sides of • Private Arrival & Departure • Daily Breakfast Marrakesh Tour Airport Transfers • Private Majorelle Garden Tour MARRAKESH: Arrive at Marrakesh Airport and meet your driver for a private transfer to your hotel. After checking in, the remainder of the day is open, and you are free to relax or explore the city on your own. (Accommodations, Marrakesh) MARRAKESH: After breakfast at your hotel, your knowledgeable English-speaking guide will meet you and begin a riveting deep dive into the hidden and authentic facets of Marrakesh. The experience will start at one of the gates of the Medina of Marrakesh - the old fortified citadel that's now designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. -

MOROCCO Morocco

Chefchaouen Atlantic Ocean AFRICA Moulay Idriss Colours of Rabat Fez Meknes Casablanca MOROCCO Morocco Marrakesh Boumalne Dades 2020 March 25 — April 8 EssaouriaEssaouira Aït Benhaddou Merzouga 2020 April 8 — April 22 Ouarzazate 2020 October 12 — October 26 2021 March 24 — April 7 2021 April 7 — April 21 2021 October 11 — October 25 2021 October 27 — November 10 DAYS 1 & 2 GOODBYE CANADA, ASALAM MOROCCO! DAY 9 VALLEY OF ROSES, AÏT BENHADDOU AND MARRAKESH Enjoy a private car ride to the airport. Travellers departing from the Toronto “Try, try! It’s good for your skin!” Our first stop on the road to Marrakesh is airport are assisted with their check-in. Meet your dedicated Group Guru Kelaat M’Gouna (Valley of Roses), celebrated for its fragrant rose products. and fellow travellers and fly overnight to Casablanca. Upon arrival, explore In Ouarzazate, the Kasbah offers views over the rugged landscape featured the Royal Palace, Mohammed V Square and Hassan II Mosque, whose in Oscar-winning films. Nearby, discover the pre-Saharan habitats of Aït minaret soars 175 meters above the city. After arriving in Rabat, raise a Benhaddou before crossing the Tizi n’Tichka, Morocco’s highest mountain toast during our welcome cocktail. Overnight in Rabat. (L,D) pass, on your final stretch to Marrakesh. Settle into your hotel and overnight in Marrakesh. (B,L,D) DAY 3 EXPLORE RABAT AND CHEFCHAOUEN (249 KM) Guided tour of buzzing Rabat. Explore the Royal Palace and Kasbah of DAY 10 DISCOVER MARRAKESH the Udayas. Cross into the Rif Mountains to access the charming blue city Your senses will tingle, and that means you are doing it right. -

Marrakesh Travel Information

Travel Information Conference Hotel: The Grand Mogador Menara Avenue Mohammed VI Marrakesh (Morocco) https://www.mogadorhotels.com/MH/Recherche/Show?hotel=5 From the airport to Grand Mogador Menara: 1) From the airport in Casablanca: Take a Casablanca Voyageur train to Marrakesh (the destination is the airport). You can purchase your one-way ticket for 212 DH (first class) or 138 DH (second class). Round-trip tickets are also available. See here for more information. 2) From the airport in Marrakesh: It is easiest to take a taxi to the hotel from the airport. It will be about a 15-minute ride and the price should be 100-150 DH. Some tips from travel sites: Taxis: According to many travel websites, it’s best to agree with your cab driver the amount you’ll be paying before the journey begins and to be sure the meter is running. Also, if you’re staying in a hotel, you can inquire the amount they advise a cab journey to be and then pitch it to the cab driver when you get in, usually they happily agree to it after sometimes trying to haggle a little. You can read some tips here and here. Clothing: As in any country, the idea is to respect the locals. This means that it is appreciated when people dress "modestly." For women, it could be a good idea to have with you something that covers your arms. However, Marrakesh is a tourist city, so the people are used to have people dress the way they want. The streets are also often uneven or cobbled so bring sensible and comfortable shoes for all the walking you’ll be doing.