Milankovitch Cycles and the Earth's Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteorology Climate

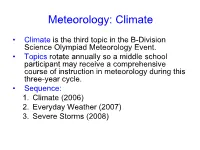

Meteorology: Climate • Climate is the third topic in the B-Division Science Olympiad Meteorology Event. • Topics rotate annually so a middle school participant may receive a comprehensive course of instruction in meteorology during this three-year cycle. • Sequence: 1. Climate (2006) 2. Everyday Weather (2007) 3. Severe Storms (2008) Weather versus Climate Weather occurs in the troposphere from day to day and week to week and even year to year. It is the state of the atmosphere at a particular location and moment in time. http://weathereye.kgan.com/cadet/cl imate/climate_vs.html http://apollo.lsc.vsc.edu/classes/me t130/notes/chapter1/wea_clim.html Weather versus Climate Climate is the sum of weather trends over long periods of time (centuries or even thousands of years). http://calspace.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/ climatechange1/07_1.shtml Weather versus Climate The nature of weather and climate are determined by many of the same elements. The most important of these are: 1. Temperature. Daily extremes in temperature and average annual temperatures determine weather over the short term; temperature tendencies determine climate over the long term. 2. Precipitation: including type (snow, rain, ground fog, etc.) and amount 3. Global circulation patterns: both oceanic and atmospheric 4. Continentiality: presence or absence of large land masses 5. Astronomical factors: including precession, axial tilt, eccen- tricity of Earth’s orbit, and variable solar output 6. Human impact: including green house gas emissions, ozone layer degradation, and deforestation http://www.ecn.ac.uk/Education/factors_affecting_climate.htm http://www.necci.sr.unh.edu/necci-report/NERAch3.pdf http://www.bbm.me.uk/portsdown/PH_731_Milank.htm Natural Climatic Variability Natural climatic variability refers to naturally occurring factors that affect global temperatures. -

Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses

Climate change and human health RISKS AND RESPONSES Editors A.J. McMichael The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia D.H. Campbell-Lendrum London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom C.F. Corvalán World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland K.L. Ebi World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, European Centre for Environment and Health, Rome, Italy A.K. Githeko Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya J.D. Scheraga US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA A. Woodward University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2003 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Climate change and human health : risks and responses / editors : A. J. McMichael . [et al.] 1.Climate 2.Greenhouse effect 3.Natural disasters 4.Disease transmission 5.Ultraviolet rays—adverse effects 6.Risk assessment I.McMichael, Anthony J. ISBN 92 4 156248 X (NLM classification: WA 30) ©World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dis- semination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution—should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Late Pliocene Climate Variability on Milankovitch to Millennial Time Scales: a High-Resolution Study of MIS100 from the Mediterranean

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 228 (2005) 338–360 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Late Pliocene climate variability on Milankovitch to millennial time scales: A high-resolution study of MIS100 from the Mediterranean Julia Becker *, Lucas J. Lourens, Frederik J. Hilgen, Erwin van der Laan, Tanja J. Kouwenhoven, Gert-Jan Reichart Department of Stratigraphy–Paleontology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, Netherlands Received 10 November 2004; received in revised form 19 June 2005; accepted 22 June 2005 Abstract Astronomically tuned high-resolution climatic proxy records across marine oxygen isotope stage 100 (MIS100) from the Italian Monte San Nicola section and ODP Leg 160 Hole 967A are presented. These records reveal a complex pattern of climate fluctuations on both Milankovitch and sub-Milankovitch timescales that oppose or reinforce one another. Planktonic and benthic foraminiferal d18O records of San Nicola depict distinct stadial and interstadial phases superimposed on the saw-tooth pattern of this glacial stage. The duration of the stadial–interstadial alterations closely resembles that of the Late Pleistocene Bond cycles. In addition, both isotopic and foraminiferal records of San Nicola reflect rapid changes on timescales comparable to that of the Dansgard–Oeschger (D–O) cycles of the Late Pleistocene. During stadial intervals winter surface cooling and deep convection in the Mediterranean appeared to be more intense, probably as a consequence of very cold winds entering the Mediterranean from the Atlantic or the European continent. The high-frequency climate variability is less clear at Site 967, indicating that the eastern Mediterranean was probably less sensitive to surface water cooling and the influence of the Atlantic climate system. -

The Definition of El Niño

The Definition of El Niño Kevin E. Trenberth National Center for Atmospheric Research,* Boulder, Colorado ABSTRACT A review is given of the meaning of the term “El Niño” and how it has changed in time, so there is no universal single definition. This needs to be recognized for scientific uses, and precision can only be achieved if the particular definition is identified in each use to reduce the possibility of misunderstanding. For quantitative purposes, possible definitions are explored that match the El Niños identified historically after 1950, and it is suggested that an El Niño can be said to occur if 5-month running means of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region (5°N–5°S, 120°–170°W) exceed 0.4°C for 6 months or more. With this definition, El Niños occur 31% of the time and La Niñas (with an equivalent definition) occur 23% of the time. The histogram of Niño 3.4 SST anomalies reveals a bimodal char- acter. An advantage of such a definition is that it allows the beginning, end, duration, and magnitude of each event to be quantified. Most El Niños begin in the northern spring or perhaps summer and peak from November to January in sea surface temperatures. 1. Introduction received into account. A brief review is given of the various uses of the term and attempts to define it. It is The term “El Niño” has evolved in its meaning even more difficult to come up with a satisfactory over the years, leading to confusion in its use. -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

Effects of Climate Change on Sea Levels and Inundation Relevant to the Pacific Islands

PACIFIC MARINE CLIMATE CHANGE REPORT CARD Science Review 2018: pp 43-49 Effects of Climate Change on Sea Levels and Inundation Relevant to the Pacific Islands Jerome Aucan, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), New Caledonia. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sea level rise is a major consequence of climate change. The global sea level rise is due to a combination of the thermal expansion of the oceans (because of their warming), and an increase in runoff from the melting of continental glaciers (which adds water to the oceans). The rate of global mean sea level (GMSL) has likely accelerated during the last century, and projections predict that sea level will be 0.4 to 0.8 m higher at the end of this century around the Pacific islands. Regional variations in sea level also exist and are due to large scale current or climate features. In addition, the sea level experienced on Pacific islands can also be affected by vertical land movements that can either increase or decrease the effects of the rise in GMSL. Coastal inundations are caused by a combination of high waves, tides, storm surge, or ocean eddies. While future changes in the number and severity of high waves and storms are still difficult to assess, a rise in GMSL will cause an increase in the frequency and severity of inundation in coastal areas. The island countries of the Pacific have, and will continue to experience, a positive rate of sea level rise. This sea level rise will cause a significant increase in the frequency and severity of coastal flooding in the near future. -

Causes of Sea Level Rise

FACT SHEET Causes of Sea OUR COASTAL COMMUNITIES AT RISK Level Rise What the Science Tells Us HIGHLIGHTS From the rocky shoreline of Maine to the busy trading port of New Orleans, from Roughly a third of the nation’s population historic Golden Gate Park in San Francisco to the golden sands of Miami Beach, lives in coastal counties. Several million our coasts are an integral part of American life. Where the sea meets land sit some of our most densely populated cities, most popular tourist destinations, bountiful of those live at elevations that could be fisheries, unique natural landscapes, strategic military bases, financial centers, and flooded by rising seas this century, scientific beaches and boardwalks where memories are created. Yet many of these iconic projections show. These cities and towns— places face a growing risk from sea level rise. home to tourist destinations, fisheries, Global sea level is rising—and at an accelerating rate—largely in response to natural landscapes, military bases, financial global warming. The global average rise has been about eight inches since the centers, and beaches and boardwalks— Industrial Revolution. However, many U.S. cities have seen much higher increases in sea level (NOAA 2012a; NOAA 2012b). Portions of the East and Gulf coasts face a growing risk from sea level rise. have faced some of the world’s fastest rates of sea level rise (NOAA 2012b). These trends have contributed to loss of life, billions of dollars in damage to coastal The choices we make today are critical property and infrastructure, massive taxpayer funding for recovery and rebuild- to protecting coastal communities. -

Global Warming Impacts on Severe Drought Characteristics in Asia Monsoon Region

water Article Global Warming Impacts on Severe Drought Characteristics in Asia Monsoon Region Jeong-Bae Kim , Jae-Min So and Deg-Hyo Bae * Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-Gu, Seoul 05006, Korea; [email protected] (J.-B.K.); [email protected] (J.-M.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3408-3814 Received: 2 April 2020; Accepted: 7 May 2020; Published: 12 May 2020 Abstract: Climate change influences the changes in drought features. This study assesses the changes in severe drought characteristics over the Asian monsoon region responding to 1.5 and 2.0 ◦C of global average temperature increases above preindustrial levels. Based on the selected 5 global climate models, the drought characteristics are analyzed according to different regional climate zones using the standardized precipitation index. Under global warming, the severity and frequency of severe drought (i.e., SPI < 1.5) are modulated by the changes in seasonal and regional precipitation − features regardless of the region. Due to the different regional change trends, global warming is likely to aggravate (or alleviate) severe drought in warm (or dry/cold) climate zones. For seasonal analysis, the ranges of changes in drought severity (and frequency) are 11.5%~6.1% (and 57.1%~23.2%) − − under 1.5 and 2.0 ◦C of warming compared to reference condition. The significant decreases in drought frequency are indicated in all climate zones due to the increasing precipitation tendency. In general, drought features under global warming closely tend to be affected by the changes in the amount of precipitation as well as the changes in dry spell length. -

Milankovitch and Sub-Milankovitch Cycles of the Early Triassic Daye Formation, South China and Their Geochronological and Paleoclimatic Implications

Gondwana Research 22 (2012) 748–759 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Gondwana Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gr Milankovitch and sub-Milankovitch cycles of the early Triassic Daye Formation, South China and their geochronological and paleoclimatic implications Huaichun Wu a,b,⁎, Shihong Zhang a, Qinglai Feng c, Ganqing Jiang d, Haiyan Li a, Tianshui Yang a a State Key Laboratory of Geobiology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China b School of Ocean Sciences, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing 100083 , China c State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China d Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA article info abstract Article history: The mass extinction at the end of Permian was followed by a prolonged recovery process with multiple Received 16 June 2011 phases of devastation–restoration of marine ecosystems in Early Triassic. The time framework for the Early Received in revised form 25 November 2011 Triassic geological, biological and geochemical events is traditionally established by conodont biostratigra- Accepted 2 December 2011 phy, but the absolute duration of conodont biozones are not well constrained. In this study, a rock magnetic Available online 16 December 2011 cyclostratigraphy, based on high-resolution analysis (2440 samples) of magnetic susceptibility (MS) and Handling Editor: J.G. Meert anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) intensity variations, was developed for the 55.1-m-thick, Early Triassic Lower Daye Formation at the Daxiakou section, Hubei province in South China. The Lower Keywords: Daye Formation shows exceptionally well-preserved lithological cycles with alternating thinly-bedded mud- Early Triassic stone, marls and limestone, which are closely tracked by the MS and ARM variations. -

Weather & Climate

Weather & Climate July 2018 “Weather is what you get; Climate is what you expect.” Weather consists of the short-term (minutes to days) variations in the atmosphere. Weather is expressed in terms of temperature, humidity, precipitation, cloudiness, visibility and wind. Climate is the slowly varying aspect of the atmosphere-hydrosphere-land surface system. It is typically characterized in terms of averages of specific states of the atmosphere, ocean, and land, including variables such as temperature (land, ocean, and atmosphere), salinity (oceans), soil moisture (land), wind speed and direction (atmosphere), and current strength and direction (oceans). Example of Weather vs. Climate The actual observed temperatures on any given day are considered weather, whereas long-term averages based on observed temperatures are considered climate. For example, climate averages provide estimates of the maximum and minimum temperatures typical of a given location primarily based on analysis of historical data. Consider the evolution of daily average temperature near Washington DC (40N, 77.5W). The black line is the climatological average for the period 1979-1995. The actual daily temperatures (weather) for 1 January to 31 December 2009 are superposed, with red indicating warmer-than-average and blue indicating cooler-than-average conditions. Departures from the average are generally largest during winter and smallest during summer at this location. Weather Forecasts and Climate Predictions / Projections Weather forecasts are assessments of the future state of the atmosphere with respect to conditions such as precipitation, clouds, temperature, humidity and winds. Climate predictions are usually expressed in probabilistic terms (e.g. probability of warmer or wetter than average conditions) for periods such as weeks, months or seasons. -

Plio-Pleistocene Imprint of Natural Climate Cycles in Marine Sediments

Lebreiro, S. M. 2013. Plio-Pleistocene imprint of natural climate cycles in marine sediments. Boletín Geológico y Minero, 124 (2): 283-305 ISSN: 0366-0176 Plio-Pleistocene imprint of natural climate cycles in marine sediments S. M. Lebreiro Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, OPI. Dept. de Investigación y Prospectiva Geocientífica. Calle Ríos Rosas, 23, 28003-Madrid, España [email protected] ABSTracT The response of Earth to natural climate cyclicity is written in marine sediments. The Earth is a complex system, as is climate change determined by various modes, frequency of cycles, forcings, boundary conditions, thresholds, and tipping elements. Oceans act as climate change buffers, and marine sediments provide archives of climate conditions in the Earth´s history. To read climate records they must be well-dated, well-calibrated and analysed at high-resolution. Reconstructions of past climates are based on climate variables such as atmospheric composi- tion, temperature, salinity, ocean productivity and wind, the nature and quality which are of the utmost impor- tance. Once the palaeoclimate and palaeoceanographic proxy-variables of past events are well documented, the best results of modelling and validation, and future predictions can be obtained from climate models. Neither the mechanisms for abrupt climate changes at orbital, millennial and multi-decadal time scales nor the origin, rhythms and stability of cyclicity are as yet fully understood. Possible sources of cyclicity are either natural in the form of internal ocean-atmosphere-land interactions or external radioactive forcing such as solar irradiance and volcanic activity, or else anthropogenic. Coupling with stochastic resonance is also very probable. -

The Global Monsoon Across Time Scales Mechanisms And

Earth-Science Reviews 174 (2017) 84–121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev The global monsoon across time scales: Mechanisms and outstanding issues MARK ⁎ ⁎ Pin Xian Wanga, , Bin Wangb,c, , Hai Chengd,e, John Fasullof, ZhengTang Guog, Thorsten Kieferh, ZhengYu Liui,j a State Key Laboratory of Mar. Geol., Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China b Department of Atmospheric Sciences, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96825, USA c Earth System Modeling Center, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China d Institute of Global Environmental Change, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an 710049, China e Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA f CAS/NCAR, National Center for Atmospheric Research, 3090 Center Green Dr., Boulder, CO 80301, USA g Key Laboratory of Cenozoic Geology and Environment, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 9825, Beijing 100029, China h Future Earth, Global Hub Paris, 4 Place Jussieu, UPMC-CNRS, 75005 Paris, France i Laboratory Climate, Ocean and Atmospheric Studies, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China j Center for Climatic Research, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The present paper addresses driving mechanisms of global monsoon (GM) variability and outstanding issues in Monsoon GM science. This is the second synthesis of the PAGES GM Working Group following the first synthesis “The Climate variability Global Monsoon across Time Scales: coherent variability of regional monsoons” published in 2014 (Climate of Monsoon mechanism the Past, 10, 2007–2052).