"I Refuse to Die:" the Poetics of Intergenerational Trauma in the Works of Li-Young Lee, Ocean Vuong, Cathy Park Hong, and Emily Jungmin Yoon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

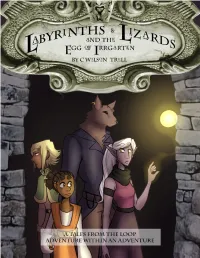

Labyrinths & Lizards Module

Labyrinths & Lizards Page !1 Labyrinths & Lizards and the Egg or Irrgarten Introduction 3 meta-Character Creation 3 meta-Classes 3 meta-Health 4 meta-Spells 4 meta-Items 5 meta-Name 5 A fnal note about notes. 5 Deep in the Labyrinth... 6 Room 1 10 Room 2 12 Room 3 15 NEXT CHALLENGE 18 Smashing the Harness Engine 20 Once it is all over 20 End of the game 20 Plunder Chart 21 meta-NPCs 22 Prerolled meta-Characters 23 Lolinda 23 MoonDaze 23 Capt. Cheese 23 Trizz 23 Acknowledgements 24 IMPORTANT NOTE: Tis game was designed to play with the Tales from the Loop RPG core book. Request it at your local game store or visit their sight, you will not be disappointed. http://frialigan.se/en/ Labyrinths & Lizards Page !2 Introduction Labyrinths & Lizards is a module I created to help my new players with transitioning from a fantasy hack-n-slash style to a more story building-mystery based RPG like Tales from the Loop. The idea came from my experiences joining an after school RPG club back in my early teens (in the 80s that actually was). This was around the same age an time period of Tales from the Loop so I felt it was a perfect idea to help introduce the players. In Labyrinths & Lizards, their player-characters travel to the North Street Rec Center and play a mini meta-RPG with an NPC named Joshua (who later became a major NPC in our campaign). Players will use their Tales from the Loop PCs skills to roll the dice for their meta-Characters., and each room is designed to help them learn and understand their STATS & SKILLS for the Tales from the Loop game. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Karaoke with a Message – September 29, 2018 a Project of Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere at Interference Archive (314 7Th St

Another Protest Song: karaoke with a message – September 29, 2018 a project of Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere at Interference Archive (314 7th St. Brooklyn, NY 11215) karaoke provided by All American Karaoke, songbook edited by Angel Nevarez & Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 Logic/Alessia Cara/Khalid A 614 A Beautiful Life Ace -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Pdf, 313.03 KB

00:00:00 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs. A fun, funky instrumental. 00:00:05 Morgan Host Hello, I’m Morgan Rhodes. My co-host Oliver Wang is away, but will Rhodes be back next week. So today it’s just me; and you are listening to Heat Rocks. Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock, you know, incendiary material, an album that feels like fire shut up in your bones; and today, we will be taking it back together to revisit a compilation record released by ABKCO Records called Sam Cooke: Portrait of a Legend. 00:00:32 Music Music “Nothing Can Change This Love” off the album Portrait of a Legend by Sam Cooke. A slow, tender song. If I go, a million miles away I'd write a letter, each and everyday Cause honey nothing, nothing can ever change this love I have for you 00:01:00 Morgan Host What a beautiful challenge that had to have been, taking a voice like Sam Cooke’s, a career like Sam Cooke’s, a discography like Sam Cooke’s, and a life like Sam Cooke’s, and compiling 30 gems on a project. ABKCO Records did just this, releasing a Portrait of a Legend on June 17th, 2003. The compilation, bookended by two gospel tracks, “Touch The Hem Of His Garment”, and “Nearer to Thee”, covers the years 1951-1964, from Sam’s humble beginnings as one of the stars of an all-star gospel group, the Soul Stirrers, to pop sensationalism, chief crooner, to fallen star, to legend. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

Buntgemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB

Seite 1 von 284 -BuntGemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Hey, hey Helen 3:15 ABBA - ABBA - 1975 (LP-192) ABBA 2 Eagle 5:48 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 3 Take a chance on me 4:00 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 4 One man, one woman 4:34 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 5 The name of the game 4:53 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 6 Move on 4:39 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 7 Thank you for the music 3:47 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 8 I wonder 4:31 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 9 When i kissed the teacher 3:01 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 10 Dancing queen 3:51 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 11 My love, my life 3:51 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 12 Knowing me, knowing you 4:01 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 13 Money money money 3:06 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 14 That's me 3:16 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 15 Why did it have to be me 3:19 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 16 Tiger 2:54 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 17 The winner takes it all 4:56 Golden Love Songs 15 - I'll Write A Song For You (RS) ABBA 18 Fernando 4:15 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 19 S.O.S. 3:22 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 20 Ring ring 3:07 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 21 Nina, pretty ballerina 2:53 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 22 Honey honey 2:57 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 23 So long -

Awaken Healing Energy Through the Tao

- 1 - Awaken Healing Energy through the Tao Taoist Secret of Circulating Internal Energy Mantak Chia Edited by: Sam Langberg - 2 - Copy Editor: Sam Langberg Editorial Assistance: Micheal Winn, Robin Winn, Contributing Writers: Dr. Lawrence Young, Dr. C.Y. Hsu, Gunther Weil, Ph.D Illustrations: Susan MacKay Final Revised Editing: Jean Chilton © Mantak Chia First published in 1983 by: Aurora Press ISBN: 974-85392-0-2 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 83-71473 Manufactured in Thailand Tenth Printing, 2002 Universal Tao Publications 274/1 Moo 7, Luang Nua, Doi Saket, Chiang Mai, 50220 Thailand Tel (66)(53) 495-596 Fax: 495-853 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.universal-tao.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission from the author except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. - 3 - Contents Contents Contents................................................................................ i About the Author .................................................................... viii Acknowledgements............................................................... xii Word of Caution .................................................................... xiii Foreward ............................................................................... xiv Introduction............................................................................ xvi Commentary ......................................................................... -

Animation Karaoké

F IE ST A G E N C Y F IE S ChanterT ? CommentA ça marche ? Dans un premier temps, choisissez votreG titre dans ce catalogue, puis inscrivez bien lisiblement sur le ticket ci-dessous (que vous trouverez auprès de votre DJ animateur ou sur les tables) votre prénom, le titre et l’artiste que vous avez choisi d’interpréter, rajouter la référence pour les Etitres en hébreu. Déposez votre ticket auprès du DJ, on vous appelera au micro ! Laissez-nousN votre email pour être au courant de nos prochains événements ! C INSCRIPTION KARAOKÉ Vous vous appelez : .......................................................................... Y Titre : ................................................................................... Artiste : ........................................................................................ Votre email : ................................................................................ Création et animation d’événements Communication événementielle 06 29 23 50 26 [email protected] AnimationAnimation KaraOkéKaraOké F IE ST A G E Inscriptions auprès de Jacky TORDJMAN-HASSAN,N Votre disc-jockey animateurC Y Création et animation d’événements Communication événementielle 0606 2929 2323 5050 2626 1 bon F IE S L’utilisationT du micro CommentA ça fonctionne ? Les micros pour le chant sont unidirectionnels. Il faut donc que le micro soit perpendiculaire à vos lèvres et non parrallèle au corps et le plus près possible de votre bouche. Il ne faut jamais tapoter sur Gle micro, et à éviter pour les effets de larsen (sifflements)