Free Range Aoudad Offer Challenging Hunt Page 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Snoball Royalty Announced Dilli

See 3 page See page 2 See page 5 See page 6 Rose Hill High School HE OCK- T EWS Volume 13 IssueT 7 710 S RoseR Hill Road, Rose Hill, KS I67133 NDecember 6, 2013 2013 Snoball royalty announced dilli. Kristin Donaldson King said, “!ank you for voting for me, Photography Editor you’re awesome!” “To the people who voted for me I !is years’ 2013 Snoball King and would like to say ‘!ank you! I appreciate Queen candidates are Paige Decker, Kayli it.’” said Haydock. Helton, Emily Terrell, Jaden Campidilli, Helton said, “I would like to give a big Harrison Haydock, and Christian Bou- thanks to the people who voted for me, dreaux with the senior class. you all make me smile. I love you all to the Our prince and princess candidates moon and back.” are Kayla King, Madison Fuller, Brooke Campidilli is of the belief that he is Wheeler, Brady Mounts, Greg Tinkler, going to be the one to win King. Haydock and Jaden Nussbaum with the junior class. said, “I think I have a good chance of win- Getting nominated is a huge deal! ning. I’m going to try to win it this year as Helton said, “I feel really honored and it king.” makes me more excited for the dance. Plus Fuller said, I don’t think I’m going to I get in the dance for free!” win but getting nominated was good “It’s really cool being nominated for enough.” Snoball candidate. It’s the #rst time I’ve King said, “It is an honor to just be been nominated for something like this!” elected even if I don’t win. -

Lawton Community Schools Graduates Small School Attention; Big School Opportunities Go Blue Devils!

Lawton Community Schools Graduates Small School Attention; Big School Opportunities Go Blue Devils! The following notes are responses to a Facebook Alumni Challenge to submit their college and career success. Congratulations and thank you for sharing your success! Jennifer L Wagonmaker-Dale Southwestern Michigan College and WMU for undergrad. Eastern Michigan University for graduate. Now National Director of Medicare Operations for a national health care organization. Tabiatha Kay US Army Kasi Fields Grand valley state university! Bachelor of arts in public relations and advertising with a Spanish minor Candie Meyer Kalamazoo Valley Community College Certified Medical Assistant!!!! Michelle R. Kinney-Miller Lake Superior State University Bachelor's of Science in Nursing, Michigan State University Master's of Science in Nursing, ANCC Nurse Practitioner...great foundation! I wouldn't trade my years at Lawton Schools! Allison Stuckey Central Michigan University for Bachelors Degree and Ball State University for Masters of Education degree. This is my tenth year teaching second grade! Thank you Lawton Schools!!! Tina Stanek Gennaro Kennesaw State College (GA) - Paralegal Certificate; Saint Leo University (FL) for BS in Computer Science. Currently working on my Masters in Instructional Design at Saint Leo. Director/Instructor for high school Academy of Design and Technology. Currently teach Game Programming Animation/Simulation. Brandy Gildea Park and Recreation degrees. Yes you can really study about running parks and recreation programs. Its not just a tv show. Bachelors from Central Michigan University and Master's from University of Illinois. Loved my years and everything I learned at Lawton Schools!! Robert Maidment West Virginia University for Sport Management and Western Michigan University for graduate school Doug Castagnasso Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice (specialization in Security Management) from Michigan State University. -

Recommendations for Public Financing National Hockey League Arenas in North America

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Master of Public Policy Capstone Projects 2019-08-31 The Price of the Puck: Recommendations for Public Financing National Hockey League Arenas in North America Puppa, Isabelle Puppa, I. (2019). The Price of the Puck: Recommendations for Public Financing National Hockey League Arenas in North America (Unpublished master's project). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111842 report Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY CAPSTONE PROJECT The Price of the Puck: Recommendations for Public Financing National Hockey League Arenas in North America Submitted by: Isabelle Puppa Approved by Supervisor: Trevor Tombe Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of PPOL 623 and completion of the requirements for the Master of Public Policy degree 1 | Page Capstone Approval Page The undersigned, being the Capstone Project Supervisor, declares that Student Name: _________________Isabelle Puppa has successfully completed the Capstone Project within the Capstone Course PPOL 623 A&B ___________________________________Trevor Tombe (Name of supervisor) Signature August 31, 2019 (Supervisor’s signature) (Date) 2 | Page Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Trevor Tombe, for his support throughout the capstone process and enthusiasm throughout the academic year. Dr. Tombe, the time you spent providing feedback and guidance has been invaluable. You’ve allowed me to express creativity in approach. You’ve been a constant guide for how to tackle policy issues. Even from over 2000 miles away—or rather, 3218 km, you were always there to help me. To my MPP classmates, your friendship is something I will always cherish. -

Parks and Recreation" to Teach Economics

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305800299 Swansonomics: Using "Parks and Recreation" to Teach Economics Article · January 2015 CITATIONS READS 0 88 2 authors, including: Brooke Conaway Georgia College 4 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Brooke Conaway on 08 November 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE EDUCATION • Volume 14 • Number 1 • Summer 2015 Swansonomics: Using “Parks and Recreation” to Teach Economics L. Brooke Conaway and Christopher Clark1 ABSTRACT Based on a first-year multidisciplinary course, Swansonomics is a class where students examine the libertarian beliefs espoused by the character Ron Swanson from the television series Parks and Recreation. The show provides great examples of rent seeking, fiscal policy issues, social policy issues, and bureaucratic incentive structures. These Parks and Recreation video clips can be used in any class to cover a variety of issues. Examples of topics include the expected economic consequences of specific political or economic philosophies, unintended consequences of policies, various systems of taxation, public and private incentive structures, and varying degrees of capitalism and government intervention. Introduction This paper is based on a first-year multidisciplinary course taught at a liberal arts university. The course covers a variety of topics, with particular emphasis on different economic systems, varying degrees of capitalism, government intervention, and public choice issues. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 43532 1 Is One Tudor, Tasha 2.1 0.5 EN 1209 EN 100 Acorns Palazzo-Craig, Janet 2.0 0.5 57450 100 Days of School Harris, Trudy 2.3 0.5 EN 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 35821 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 EN 61265 12 Again Corbett, Sue 4.9 8.0 EN 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Howe, James 5.0 9.0 EN Thirteen 14796 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4.0 EN 107287 15 Minutes Young, Steve 4.0 4.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 17.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. 9.0 12.0 EN 11592 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 EN 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 3.3 1.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 5.6 7.0 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 71428 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda, Anna 4.3 2.0 EN 68579 "A" My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 2.2 0.5 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

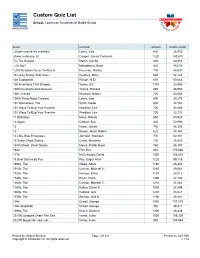

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Coachman Fundamental Middle School MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® WORD COUNT ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 26,950 último mohicano, El Cooper, James Fenimore 1220 140,610 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 40,955 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 98,676 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 58,937 10 Lucky Things That Have Hershey, Mary 640 52,124 100 Cupboards Wilson, N. D. 650 59,063 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 33,959 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 38,950 1001 Cranes Hirahara, Naomi 720 43,080 100th Thing About Caroline Lowry, Lois 690 30,273 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 44,767 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 700 37,864 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Wardlaw, Lee 700 52,733 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 650 50,929 12 Again Corbett, Sue 800 52,996 13 Howe, James 740 56,355 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 38,363 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 62,401 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 730 25,560 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 36,397 1632 Flint, Eric 650 175,646 1776 McCullough, David 1300 105,034 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 99,118 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 31,665 1950s, The Kallen, Stuart A. -

Inspired Art 4-H Alum Celebrates Iowa Roots Plus: •Hall of Fame •Citizenship •STEM •Decades of Learning •Healthy Living •Scholarship Winners •And MORE!

WINTER 2015 FourWordwww.iowa4hfoundation.org In This Issue: Inspired Art 4-H Alum Celebrates Iowa Roots Plus: •Hall of Fame •Citizenship •STEM •Decades of Learning •Healthy Living •Scholarship Winners •And MORE! On the Cover: Ellen Wagener recently donated one of her works in honor of Glen and Mary Jo Mente (pictured.) The artwork is on display in the Iowa 4-H Foundation oce. Photo Credit: Kayla Hyett Welcome New Trustees..................2 Gifts & Pledges......................... 16 Memorials .............................19 Annual Report .........................22 FourWord www.iowa4hfoundation.org Welcome Letter from Board New Board President, Tom Nicholson Trustees I am honored and excited to become the new president of the Iowa At the Iowa 4-H Foundation Annual Board 4-H Foundation Board of Trustees. Many years ago, I began my 4-H meeting in October, one new trustee and experience as a member of the Center Trail Blazers 4-H Club in Calhoun one new youth trustee were elected to County. rough 4-H, I’ve developed a passion for raising and showing serve on the Board of Trustees. livestock and gained other valuable skills in leadership, communication and teamwork that I have been able to apply in my personal life and Heather Van Nest is throughout my professional career. Now as a Warren County 4-H the Global Application parent, I’ve had the good fortune to observe my son and daughter product line marketing enjoying many of the same opportunities that 4-H provides. manager for John Deere in Ankeny, Iowa. She was Over the years, advancements in technology, a global economy, population demographics a member of the Sac City and other factors have reshaped the Iowa landscape. -

Chandra Wilson

CHANDRA WILSON AEA AFTRA SAG Management Agent Hair Color : Brown Edie Robb Richard Fisher Eye Color : Dark Brown STATION 3 ENTERTAINMENT ABRAMS ARTIST AGENCY Height : 5’0 323-848-4404 / 212-245-3250 646-486-4600 Weight : 150 lbs. FILM AUTISM IN AMERICA Narrator Skydive Films MUTED: THE MOVIE (Short) Lena Gladwell Dir. Rachel Goldberg FRANKIE AND ALICE Maxine Murdoch Lionsgate Dir. Goeffrey Sax ACCIDENTAL FRIENDSHIP Yvonne Caldwell Hallmark Channel Dir. Don McBrearty LONE STAR Athena Castle Rock/Sony Classics Dir. John Sayles PHILADELPHIA Chandra Tri Star Pictures Dir. Jonathan Demme TELEVISION THE ABCs OF SCHOOLHOUSE ROCK Host ABC/Hodder TV PRIVATE PRACTICE Guest Star ABC/ABC Studios SESAME STREET Self “Word of the Day – Half” PBS Children’s Television Workshop GREY’S ANATOMY Series Regular (12 Seasons) ABC/ABC Studios THE SOPRANOS Guest Star HBO/Soprano Productions, Inc. LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT (2) Guest Star NBC/Universal Television QUEENS SUPREME Recurring CBS Television SEX & THE CITY Guest Star HBO/Sex & the City, Inc. BOB PATTERSON Series Regular ABC/Touchstone/20th C F Television 3RD WATCH Guest Star NBC/Warner Bros Television 100 CENTRE STREET Guest Star A&E/100 Centre St, Ltd COSBY Guest Star CBS/Carsey Werner SEXUAL CONSIDERATIONS Principle CBS Schoolbreak Special LAW AND ORDER Guest Star NBC/Universal Television ONE LIFE TO LIVE Recurring ABC Television THE COSBY SHOW Guest Star NBC/Carsey Werner THEATRE CHICAGO-THE MUSICAL (Broadway) Matron Mama Morton The Ambassador Theatre CAROLINE, OR CHANGE (Broadway) Dotty Moffet The Public Theatre (Eugene O’Neill) Dir. George C. Wolfe AVENUE Q (Broadway) Gary Coleman (Cover) The Golden Theatre THE MIRACLE WORKER Viney Charlotte Repertory Theatre ON THE TOWN (Broadway) Flossie’s Friend The Delacorte (Gershwin Theatre) Dir. -

Arrows Rally at Homecoming

The WALRUS The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things: Of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings. - Lewis Carroll Vol LXVI, No. 1 St. Sebastian’s School October 2012 Arrows Rally at Homecoming successful two win-one loss race for BB&N football team, a perennial ISL By MICKEY ADAMS ‘13 the Arrows, and proved to be an excit- powerhouse for the past few years, SENIOR EDITOR ing start for the rest of Homecoming. if they wanted to stay in contention A day later, on Saturday the for the playoffs. The Arrows came out 29th, huge masses flocked to St. Se- fast, with senior running back Bren- On September 28th and 29th, the bastian’s School for the main event. dan Daly finding the end zone early to Arrows took to the course, the field, Swarms of red and black engulfed give the Red and Black a 7-0 lead after and the gridiron during the annual the turfs fields, anxiously awaiting they converted the extra point. BB&N Homecoming festivities. In front the start of the JV and Varsity Soccer soon responded though, putting to- of huge crowds of fellow students, games, as well as the Varsity Foot- gether what was really their only effec- teachers, parents, alumni, and ball game. All of our athletes were tive drive of the game, and it resulted many others, the St. Sebastian’s fall pitted against talented squads from in six. The Arrows had looked pretty sports teams showcased nothing BB&N, and at the end of the day, good in the first half, and took a 7-6 short of excellence. -

Tri Polar World Turns – Tri Polar World 3.0 January 24Th, 2020

As The Tri Polar World Turns – Tri Polar World 3.0 January 24th, 2020 As we begin a new decade it's a good time to both think through some recent Tri Polar World (TPW) developments and consider what the future might hold. From its NAFTA related origin over 25 years ago to its TPW 2.0 iteration post the 2008-9 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) through to Brexit, the Trump presidency and the US - China trade fight, the TPW construct has continued to evolve. Focused on regional integration in the three main regions of Asia, Europe & the Americas, it has been a useful way to think about geo politics, the world economy & financial markets. More recently, the sharpening of US - China tech competition and the rapid rise of climate concerns have provided the outlines for the next phase of TPW’s evolution. These include “Splinternet” to describe the separation of tech into two distinct, US and China led camps, with Europe playing the role of regulator. There is also the growing web of issues around the cost- benefits of tech, ranging from privacy and data concerns to antitrust and digital tax issues. On the climate side, Europe is fast becoming the regional standard bearer for climate action as it becomes evident that climate change will not be dealt with globally (US to withdraw from the Paris Accord) nor locally as the smoke from the bushfires of Australia affecting New Zealand air quality illustrates. Let's start with a review of the TPW construct, its origin, evolution and main drivers. -

Parks and Recreation Season 3 Bbc

Parks and recreation season 3 bbc Leslie tries to convince Chris and Ben to give the parks department more money. Parks and Recreation Episodes Episode guide 12/16 The neighbouring city of Eagleton puts up a fence around one of their parks. Series 3 homepage. Tom attempts to shine down the charm ray to convince Ethel to do his work for him. The third season of Parks and Recreation originally aired in the United States on the NBC television network between January 20 and May 19, Like the Original release: January 20 – May 19, Parks and Recreation has evolved into one of the funniest sitcoms on either side of the Atlantic, says Patrick Smith. Parks and Recreation Season 3: Watch online now with Amazon Instant Video: I'm so glad BBC picked it up because I have bought each DVD as soon as it's. Preview and download your favourite episodes of Parks and Recreation, Season 3, or the entire series. and Adam Scott) permanently join the Parks and Recreation staff in . If BBC don't want it, someone else pick it up. Other Sign in options · Parks and Recreation (TV Series –) Poster Season 3. Go Big or Go Home. S3, Ep1. 20 Jan. Go Big or Go Home. Retta putting her weave in the time capsule is forever one of my favorite pieces of comedy from the last few years. Synopsis: Eternally optimistic government employee Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler) sets her sights on a new goal in series 3: revitalizing the town of Pawnee by. Parks and Recreation is back! Bully. -

ROMANOWSKI-THESIS-2018.Pdf (1.018Mb)

ABSTRACT “Our Real Family, The One We Chose”: The Function of Comfort in the Sitcom Family Max Romanowski, M.A. Thesis Chairperson: James M. Kendrick, Ph.D. Throughout history, the situation comedy (or “sitcom”) has continually been used as a form of comfort for the viewer. The original sitcoms of the 1950s were filled with themes that reinforced the stability of the traditional family model after the cultural shifts during the world wars. While that style of sitcom and its family has changed, its function to viewers has largely remained the same. While it no longer is about reinforcing a traditional family structure, the sitcom does work to comfort the viewers that are watching. This study works to examine how and why the sitcom family has evolved, what the new sitcom family looks like today, and what that means for societal values. The sitcoms Friends (1994), The Office (2005), Parks and Recreation (2009), Brooklyn Nine-Nine (2013), and Community (2009) will be used as case studies to understand the new dominant type of sitcom family: The constructed family. iv "Our Real Family, The One We Chose": The Function of Comfort in the Sitcom Family by Max Romanowski, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Communication David W. Schlueter, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee James M. Kendrick, Ph.D., Chairperson Mark T. Morman, Ph.D. Robert F. Darden, M.A. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2018 J.