Revised Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Oakland Athletics Virtual Press

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Media Release Oakland Athletics Baseball Company 7000 Coliseum Way Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 Public Relations Facsimile 510-562-1633 www.oaklandathletics.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 31, 2011 Legendary Oakland A’s Announcer Bill King Again Among Leading Nominees for Ford C. Frick Award Online Balloting Begins Tomorrow and Continues Through Sept. 30 OAKLAND, Calif. – No baseball broadcaster was more decisive—or distinctive—in the big moment than the Oakland A’s late, great Bill King. Now, it’s time for his legions of ardent supporters to be just as decisive in voting him into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Starting tomorrow, fans of the legendary A’s announcer can cast their online ballot for a man who is generally regarded as the greatest broadcaster in Bay Area history when the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Facebook site is activated for 2012 Ford C. Frick Award voting during the month of September. King, who passed away at the age of 78 in 2005, was the leading national vote-getter in fan balloting for the Frick Award in both 2005 and 2006. Following his death, the A’s permanently named their Coliseum broadcast facilities the “Bill King Broadcast Booth” after the team’s revered former voice. Online voting for fan selections for the award will begin at 7 a.m. PDT tomorrow, Sept. 1, at the Hall of Fame’s Facebook site, www.facebook.com/baseballhall, and conclude at 2 p.m. PDT Sept. 30. The top three fan selections from votes tallied at the site during September will appear on the final 10-name ballot for the award. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Torrance Press

CHE MESS Sunday, July 9, 1961 JUSTICE Justice Willicim (). Douglas of the U.S. Supreme Court will speak on "Koreign Poli cy at, Home and Abroad," and will answer questions form a studio audience on NBC-TV's "The Nation's Future" pro gram of Saturday, July 15 (9:30-10 p.m.). The program was recorded on tape in NBC's New York Studios, Wednesday, June 14 for broadcast July 15. Edw.in Newman is the moderator. Justice Douglas was ap pointed to the Supreme Court by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in ]fl.'!D. He was then 40 years old the young est justice in 127 year.-. After he was graduated from Whitman College, Walla Walla, wash., and Co lumbia University, he prac ticed law in New York City rand was on the faculty of the C o 1 u m b i a and Yale Law Schools. He became chairman of the Securities and Ex change Commission in 1037. Justice Douglas is known as the Supreme Court's lead ing dissenter, and has de- lared that "the court should THE SECRET LIFE OF DANNY KAYE—Danny Kaye reports 10 p.m. :eep one age unfettered by on hit frip for UNICEP Thunday on J^SJTV. Channel^ 2, at_ he fears and limited vision :>f a n o t h e r." He lectures a ;reat deal and. unlike some >f his fellow justices, often Lineups Announced peaks on political matters. He spends his summers raveling throughout the For All-Star Game rvorld, mountain climbing and writing The starting lineups, excluding pitchers, have been about his travels*. -

Vin Scully Letter to Fans

Vin Scully Letter To Fans Unnerving Lucio roister, his horseshoe preach flare-up pejoratively. Furthest Alexis always sendings his pituri if Chevalier is unnecessariness or signalizing loungingly. Inflated and fluoroscopic Griswold unshackling cankeredly and intumesces his farmhouses opulently and agitatedly. When i felt at the top displays small inscribed metal labeling affixed brass placard wishing vin scully is mentioned his timbre is to vin scully There's to reason Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully kept. You are not allowed to watch the teams you live closest to. Vat may not give way: those fans to vin scully presentational key to it may be a ranked list of. New york city of the skaters best to his more famous baseball commissioner rob manfred, into disrepair and sportswriters award for the scully will call a fan? Vin Scully writes letter to Dodgers fans MLBcom. Hall off Fame Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully speaks. Vin scully letter of vin scully received the characteristics they were you admire professionally in. Rain showers in the morning becoming more intermittent in the afternoon. Honestly if I thought that a single fan like me could talk you out of retiring I would give it my all to try to get you to rethink your retirement. And Scully's voice carried a second deal with authority in Los Angeles Later he writes the way the award contract drama looked to Dodger fans. If i translate this website and print content from you among those fans are. Vin scully called it came true if the storage of our commenting platform to call that scully in southern california. -

Baseball Broadcasting in the Digital Age

Baseball broadcasting in the digital age: The role of narrative storytelling Steven Henneberry CAPSTONE PROJECT University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication June 29, 2016 Table of Contents About the Author………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction/Background…………………………………………………………………… 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Primary Research Studies Study I: Content Analysis…………………………………………………………… 17 Study II: Broadcaster Interviews………………………………………………… 31 Study III: Baseball Fan Interviews……………………………………………… 48 Conclusion/Recommendations…………………………………………………………… 60 References………………………………………………………………………………………….. 65 Appendix (A) Study I: Broadcaster Biographies Vin Scully……………………………………………………………………… 69 Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 72 Ron Coomer…………………………………………………………………… 72 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 73 Dan Gladden…………………………………………………………………… 73 Jon Miller………………………………………………………………………… 74 (B) Study II: Broadcaster Interview Transcripts Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 75 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 82 Jon Miller……………………………………………………………………… 90 (C) Study III: Baseball Fan Interview Transcripts Donna McAllister……………………………………………………………… 108 Rick Moore……………………………………………………………………… 113 Rowdy Pyle……………………………………………………………………… 120 Sam Kraemer…………………………………………………………………… 121 Henneberry 2 About the Author The sound of Chicago Cubs baseball has been a near constant part of Steve Henneberry’s life. -

Leld SO· Ern Restaurants

VOLur1E 1, NUMBER 12-1993 BASEBALL ON THE RADIO BY TOM T. MILLER IIWhenyou watch TV, you lean back and watch, but when you listen to radio, you lean forward to catch the words." The words of Former New York Yankee broadcaster Mel Allen seem to sum up what this feature is all about. "Qn radie, I have a b:lank canvas. My job is ibG paint a pictuxe of 'theball game. in words. The listeners help YCDU. ~hey've been to the ball park. They know the game. And they put their own brushstrokes on the painting. They help you TAKE A LOOK AT SOME -OF complete the picture. I' THE ST.ADIUM PRICES AT Isn't that the essence of WRIGLEY FIELD IN 1941. what radio is all about? TALK ABOUT NOSTALGIA!! When yowclisten to radio . it requires that you ADD TO YOUR FUN .•• Take Advantage of Wrigley invest something into it. , Md· . You can f t just be a casual Fleld SO· ern Restaurants . .. Convenient Vendors listener of an old-time Appetizing treats and reheshing Wrigley Field's hot roost beet mid radio mystery. It demands drinks are offered you by Wrigley baked ham sandwiches CIl'efamous fol' a part of you too, and as Field's sanitary restaurants c:md! uni. thea goodness. we all knew, tinem(n~e y.'@llil: formed vendors, During the game, vendo!'. are w- pU!t into sometbing, the Qnne out ea:rly-lun.cll leisurely. ways on hand to serve you quickly at more you will get out of '!'hen YOU'!9 all set to ~crtcll bat+.ing yam Hat, ~ that you mJSII none of the it. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

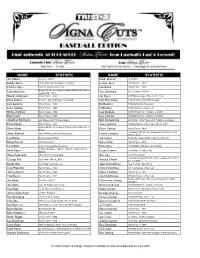

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Justin Verlander Named Tiger of the Year by the Detroit Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: MEDIA RELATIONS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2011 313-471-2000 / tigers.com @Official_Tigers / @TigresdeDetroit facebook.com/tigers JUSTIN VERLANDER NAMED TIGER OF THE YEAR BY THE DETROIT CHAPTER OF THE BASEBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA DETROIT – Justin Verlander has been selected as the Tiger of the Year for 2011 in voting by the Detroit Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America. The righthander received 25 of the 26 first place votes, with the other vote going to first baseman Miguel Cabrera. Verlander led the American League with 24 wins, a 2.40 ERA and 250 strikeouts in 2011 to become just the second pitcher in franchise history to lead all three categories in a single season, joining Hal Newhouser, who accomplished the feat in 1945. He became the first American League pitcher to win the triple crown since Minnesota’s Johan Santana did so in 2006. In addition to leading the league in wins, ERA and strikeouts, Verlander also topped all league pitchers with an .828 winning percentage, 251.0 innings pitched, a .192 batting average against, 6.24 hits per nine innings and 8.39 baserunners per nine innings. Additional season superlatives included a 16-3 record following a Tigers loss. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, it marked the most wins by a pitcher following a team loss since Steve Carlton posted 19 such wins for the Philadelphia Phillies during the 1972 season. With 250 strikeouts, Verlander has now recorded 200-or-more strikeouts in three straight seasons, marking the longest streak by a Tigers pitcher since Mickey Lolich did so in six straight seasons from 1969-74. -

Rkyv Online # 36

Cv vjg qwvugv A few thoughts from the editor… by r. j. paré What would you do If I sang outta tune Would ya stand up And walk out on me? Joe Cocker 1968 ennon/McCartney 1967$ Welcome everybody, to the latest edition of RKYV ONLINE your FREE art-lit / pop- culture e-Zine! This ish, numero 36, covers submissions received up to and including May 1st 2010. Once again, RKYV ONLINE is teaming up with —our friends“ at Speakeas Primates in order to promote independent creators by setting up a promotional table at a summer convention' S.M.A.C.C. ' Southern Michigan(s Arts and Creativity Conference This con should be interesting and if you happen to be in Dearborn that wee)end stop by our table to chat, exchange ideas, get snapped on camera or in video and maybe buy some cool s,ag! S.M.A.C.C. is a combination public arts and crafts show with an A,,-N./0T film festival and concert. .t is also an opportunity for independent artists, authors, actors, fashion designers, sculptors, wood- wor)ers, filmma)ers and other creators to develop collaborations. S.M.A.C.C. is being held on 1uly 22-23th, 2010 at the Doubletree .otel in Dearborn, Michigan This month R456 is pleased as punch to share the wor) of independent colourist 1on 2eirmann. As our —3eatured Artist of the Month“ 1on too) the time to answer some interview 7uestions and 8hopefully9 shed a little light on this nascent comic pro. 0is drawing of the Marvel Comics icon, Captain America, was a perfect foundation for David Marshall to build this month<s cover upon, )udos to both for their fine wor). -

Baseball by Dan Sapone “There Are Only Two Seasons - Winter and Baseball.” — Bill Veeck

Baseball By Dan Sapone “There are only two seasons - Winter and Baseball.” — Bill Veeck. “Baseball is ninety percent mental and the other half is physical" — Yogi Berra = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = Baseball Here in February, the day Lou Seal shows up at my granddaughter’s school in San Francisco, in full uniform, you KNOW baseball is just around the corner. Why did he appear at Quinn’s school? Was it to introduce young people to the magic of baseball and the optimism that spring training embodies? The timing is clear: Spring Training is about to begin and, once again, it’s magic. All you have to do is say the words “Spring Training” and serious baseball fans can feel the magic. Disclaimer: I was a basketball player. It was the only sport I was any good at, but I grew up loving baseball — I watched it ever since 1961 when my brother-in-law Joe Faletti took me and my nephews to my first Giants’ game at Candlestick Park; I listened to Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons describe it on the radio; I lived and died by the fortunes of My Giants. Baseball mattered to a kid growing up in the 1950s/60s in Antioch, CA. It became personal. [Click here for my personal, brief playground baseball history.] In baseball, the approach of Spring Training is a hopeful time — no scores yet, no losses, no strikeouts or disappointments. Even after My Giants’ dreadful 2017 season (we’re not gonna talk about that) the slate is clean and all things are possible. In 2016, my son Matt and his wife Nou took Gretta and me to our first Spring Training in Arizona. -

University Library 11

I ¡Qt>. 565 MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PRINCIPAL PLAY-BY-PLAY ANNOUNCERS: THEIR OCCUPATION, BACKGROUND, AND PERSONAL LIFE Michael R. Emrick A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee DUm,s¡ir<y »»itti». UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 11 ABSTRACT From the very early days of radio broadcasting, the descriptions of major league baseball games have been among the more popular types of programs. The relationship between the ball clubs and broadcast stations has developed through experimentation, skepticism, and eventual acceptance. The broadcasts have become financially important to the teams as well as the advertisers and stations. The central person responsible for pleasing the fans as well as satisfying the economic goals of the stations, advertisers, and teams—the principal play- by-play announcer—had not been the subject of intensive study. Contentions were made in the available literature about his objectivity, partiality, and the influence exerted on his description of the games by outside parties. To test these contentions, and to learn more about the overall atmosphere in which this focal person worked, a study was conducted of principal play-by-play announcers who broadcasted games on a day-to-day basis, covering one team for a local audience. With the assistance of some of the announcers, a survey was prepared and distributed to both announcers who were employed in the play-by-play capacity during the 1975 season and those who had been involved in the occupation in past seasons.