Sen's Capability Approach and Post Keynesianism: Similarities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Income Inequality and the Labour Market in Britain and the US

Journal of Public Economics 162 (2018) 48–62 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Public Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpube Income inequality and the labour market in Britain and the US Richard Blundell a,⁎, Robert Joyce b, Agnes Norris Keiller a, James P. Ziliak c a University College London, Institute for Fiscal Studies, United Kingdom b Institute for Fiscal Studies, United Kingdom c University of Kentucky, Institute for Fiscal Studies, United States article info abstract Article history: We study household income inequality in both Great Britain and the United States and the interplay between la- Received 31 October 2017 bour market earnings and the tax system. While both Britain and the US have witnessed secular increases in 90/ Received in revised form 15 March 2018 10 male earnings inequality over the last three decades, this measure of inequality in net family income has de- Accepted 2 April 2018 clined in Britain while it has risen in the US. To better understand these comparisons, we examine the interaction Available online 23 April 2018 between labour market earnings in the family, assortative mating, the tax and welfare-benefit system and house- hold income inequality. We find that both countries have witnessed sizeable changes in employment which have Keywords: Inequality primarily occurred on the extensive margin in the US and on the intensive margin in Britain. Increases in the gen- Family income erosity of the welfare system in Britain played a key role in equalizing net income growth across the wage distri- Earnings bution, whereas the relatively weak safety net available to non-workers in the US mean this growing group has seen particularly adverse developments in their net incomes. -

Human Development Research Paper 2011/06 Economic Crises And

Human Development Research Paper 2011/06 Economic crises and Inequality A B Atkinson and Salvatore Morelli United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports Research Paper November 2011 Human Development Research Paper 2011/05 Sustainability in the presence of global warming: theory and empirics Humberto Llavador, John E. Roemer, and Joaquim Silvestre United Nations Development Programme Human Development Reports Research Paper 2011/06 November 2011 Economic crises and Inequality A B Atkinson and Salvatore Morelli A B Atkinson is a Fellow of Nuffield College and Centennial Professor at the London School of Economics. E-mail: [email protected]. Salvatore Morelli is a D Phil student in the Department of Economics, University of Oxford. E-mail: [email protected]. Comments should be addressed by email to the author(s). Abstract Sustainability for a society means long-term viability, but also the ability to cope with economic crises and disasters. Just as with natural disasters, we can minimize the chance of them occurring and set in place policies to protect the world’s citizens against their consequences. This paper is concerned with the impact of economic crises on the inequality of resources and with the impact of inequality on the probability of economic crises. Is it the poor who bear the brunt? Or are crises followed by a reversal of previous boom in top incomes? Reversing the question, was the 2007 financial crisis the result of prior increases in inequality? Have previous periods of high inequality led to crises? What can we learn from previous crises – such as those in Nordic countries and the Asian financial crisis? How far can public policy moderate the impact of economic crises? Keywords: Economic crises, Poverty, Inequality. -

Income Inequality and the Labour Market in Britain and the US

UKCPR Discussion Paper Series University of Kentucky Center for DP 2017-07 Poverty Research ISSN: 1936-9379 Income inequality and the labour market in Britain and the US Richard Blundell University College London Institute for Fiscal Studies Robert Joyce Institute for Fiscal Studies Agnes Norris Keiller Institute for Fiscal Studies University College London James P. Ziliak University of Kentucky October 2017 Preferred citation Blundell, R., et al. (2017, Oct.). Income inequality and the labour market in Britain and the US. University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, DP2017-07. Re- trieved [Date] from http://www.cpr.uky.edu/research. Author correspondence Richard Blundell, [email protected] University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, 550 South Limestone, 234 Gatton Building, Lexington, KY, 40506-0034 Phone: 859-257-7641. E-mail: [email protected] www.ukcpr.org EO/AA Income Inequality and the Labour Market in Britain and the US1 Richard Blundell2, Robert Joyce3, Agnes Norris Keiller4, and James P. Ziliak5 October 2017 Abstract We study household income inequality in both Great Britain and the United States and the interplay between labour market earnings and the tax system. While both Britain and the US have witnessed secular increases in 90/10 male earnings inequality over the last three decades, this measure of inequality in net family income has declined in Britain while it has risen in the US. We study the interplay between labour market earnings in the family, assortative mating, the tax and benefit system and household income inequality. We find that both countries have witnessed sizeable changes in employment which have primarily occurred on the extensive margin in the US and on the intensive margin in Britain. -

Inequality and Banking Crises: a First Look1

1 Inequality and Banking Crises: A First Look A B Atkinson, Nuffield College, Oxford and London School of Economics Salvatore Morelli, University of Oxford 1. Introduction: inequality and financial crises 1.1 Inequality crisis 1.1 Aim and structure of the paper 1.2 Identifying crises 2. The what and which of inequality measurement 2.1 Inequality of what? 2.2 Which part of the parade should we be watching? 2.3 The data challenge 3. Inequality and crises in long-run historical perspective: the US as epicentre 3.1 Income inequality 3.2 Alternative lenses 3.3 Commonalities and differences across crises 4. Inequality and crises in long-run historical perspective: Around the world 4.1 The Nordic financial crises 4.2 Asian financial crises 4.3 A summary of 35 banking crises: clear-glass window plots 5. Initial conclusions and unfinished business Appendix A: Inequality and banking crises in 14 countries not covered in the main text. Appendix B: Window plots for 32 banking crises References 1 Paper prepared for the Global Labour Forum in Turin organised by the International Labour Organization, which provided financial support for one of the authors (SM). The research forms part of the work of the Institute for Economic Modelling (EMoD) at the University of Oxford, supported by the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) and the Oxford Martin School. The paper was written while one of the authors (ABA) was visiting the Department of Economics, Harvard University, and one (SM) was visiting the NBER. The hospitality of these institutions is gratefully acknowledged. -

The Legacy of Tony Atkinson in Inequality Analysis

THE LEGACY OF TONY 2nd LIS/LWS Users ATKINSON IN INEQUALITY Conference ANALYSIS Tony Atkinson is considered as a true European and internationalist dedicated to reducing poverty everywhere: «To make progress happen, you have to believe, optimistically, that progress is possible». 0 Luxembourg, Tony’s last Executive Committee meeting with us - July 2016. From left to right: Serge Allegrezza, Reeve Vanneman, Janet Gornick, Tony Atkinson, Paul van der Laan, Thierry Kruten and Daniele Checchi. Contents: Tony Atkinson and the Luxembourg Income Study–LIS ........................................... 3 A. Brandolini, D. Checchi, J. Gornick, T. Smeeding Labour Income, Social Transfers and Child Poverty ................................................. 7 B. Bradbury, M. Jäntti, L. Lindahl Women’s Employment Growth Associated with Only Modest Poverty Reductions in 15 OECD Countries, 1971-2013 ....................................................... 12 B. Cantillon , D. Collado, R. Nieuwenhuis, W. Van Lancker Doing Better for Single-Parent Families, Redistribution and Work-Family Policy in 45 Countries ............................................................................................. 16 L.C. Maldonado The Inequality of Equal Mating .............................................................................. 20 R. Aaberge, J.T. Lind, K. Moene Extreme Child Poverty in Rich and Poor Nations: Lessons from Atkinson for the Fight against Child Poverty .............................................................................. 24 Y. Cai, T. -

Ahmad Michael Best

Working paper Financing Social Policy in the Presence of Informality Ehtisham Ahmad Michael Best March 2012 Financing Social Policy in the Presence of Informalityú Ehtisham Ahmad (ZEF, Bonn & Asia Research Centre, LSE) Michael Best (STICERD and Department of Economics, LSE)† 31st March 2012 Abstract We present a framework for the analysis of tax and benefit policy in countries with significant informality. Our framework allows us to jointly analyse the effects of various taxes and benefits on incentives for firms and workers to be informal and evade taxation. We find that payroll taxes and targeted minimum income guarantees targeted to households without formal employment are particularly harmful to labour formality and participation in the modern sector labour force. Conversely, Bismarkian benefits targeted to formal sector workers and basic benefits targeted to low income households represent the least distortionary way to redistribute. Attempts to use holes in the VAT to “protect” the poor are generally ineffective and open up avenues for rent seeking. We also find that a uniform value added tax and a corporate income tax represent the least distortionary way to raise revenues. The information generated from a simple VAT can be used, given an appropriately designed tax administration, to enhance the probability of detection of informal activities. Distributional issues are best handled by social policy and the personal income tax. Indeed, given the gainers and losers from tax reforms, social policies and intergovernmental transfers will be needed to ensure the political acceptance of the reforms. The precise mix of taxation and social policy will vary given different country characteristics and institutional structures. -

The Royal Economic Society Agenda

THE ROYAL ECONOMIC SOCIETY NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of the Society will be held in Room Jubilee 144 of the Jubilee Building, University of Sussex, BN1 9SL on Tuesday 22nd March 2016 at 12.30. AGENDA 1. To adopt the Minutes of the 2015 Annual General Meeting (attached) 2. To receive and consider the Report of the Secretary on the activities of the Society 3. To receive the annual statement of accounts for 2015 4. To discuss and decide questions in regard to the affairs and management of the Society a. To ratify the Executive Committee Statement of the alteration to the term of the Presidency (attached) 5. To elect Vice-Presidents and Councillors for the ensuing year (the current Councillors are listed.) a. Council recommends that Professor Andrew Chesher be ratified as President b. Council recommends that Professor Peter Neary be ratified as President-elect c. Following a ballot of the members of the Society, Council recommends the following six members be elected to serve on the Council until 2020: Professor Christian Dustmann (UCL) Professor Amelia Fletcher (UEA) Professor Rafaella Giacomini (UCL) Professor Beata Javorcick (Oxford) Professor Paola Manzini (St Andrews) Professor Tim Worrall (Edinburgh) 6. To appoint Auditors for the current year 7. Any Other Business Denise Osborn (Professor Emeritus, Manchester), Secretary-General. THE ROYAL ECONOMIC SOCIETY Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the Society held at University Place, the University of Manchester on Tuesday 31st March 2015 at 12.30. There were present: The President-elect Professor John Moore, the Honorary Treasurer, Mark Robson; the Secretary-General, Professor John Beath; the Secretary-General elect (Professor Denise Osborn), the Second Secretary (Robin Naylor), members of the Executive Committee and approximately 40 other members. -

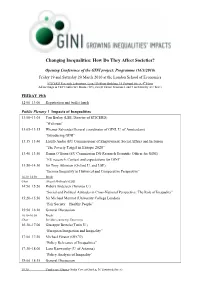

Changing Inequalities: How Do They Affect Societies?

Changing Inequalities: How Do They Affect Societies? Opening Conference of the GINI project: Programme (16/3/2010) Friday 19 and Saturday 20 March 2010 at the London School of Economics STICERD Research Laboratory, Lionel Robbins Building, 10 Portugal Street, 4th Floor All meetings in CEP Conference Room (405), except Theme Sessions 1 and 4 on Saturday (see there) FRIDAY 19th 12:00–13:00 Registration and buffet lunch Public Plenary 1 Impacts of Inequalities 13:00–13:05 Tim Besley (LSE, Director of STICERD) “Welcome” 13:05–13:15 Wiemer Salverda (General coordinator of GINI, U. of Amsterdam) “Introducing GINI” 13:15–13:40 László Andor (EU Commissioner of Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion “The Poverty Target in Europe 2020” 13:40–13:50 Ronan O’Brien (EU Commission DG Research Scientific Officer for GINI) “EU research: Context and expectations for GINI” 13:50–14:30 Sir Tony Atkinson (Oxford U. and LSE) “Income Inequality in Historical and Comparative Perspective” 14:30–14:50 Break Chair Abigail McKnight (LSE) 14:50–15:20 Robert Andersen (Toronto U.) “Social and Political Attitudes in Cross-National Perspective: The Role of Inequality” 15:20–15:50 Sir Michael Marmot (University College London) “Fair Society – Healthy People” 15:50–16:10 General Discussion 16:10–16:30 Break Chair Ive Marx (Antwerp University) 16:30–17:00 Giuseppe Bertola (Turin U.) “European Integration and Inequality” 17:00–17:30 Michael Förster (OECD) “Policy Relevance of Inequalities” 17:30–18:00 Lane Kenworthy (U. of Arizona) “Policy Analysis of Inequality” 18:00–18:15 General Discussion 19:30 Conference Dinner (Sofra Covent Garden, 36 Tavistock Street) 2 SATURDAY 20th Project Plenary Organisation and Methods of the GINI Project [9:00–10:30] 9:00– 9:15 Wiemer Salverda “Organising GINI” 9:15– 9:30 Brian Nolan and Ive Marx “Income Inequality Methodology” 9:30– 9:50 Herman van de Werfhorst et al. -

Nber Working Paper Series the Idea of Antipoverty

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE IDEA OF ANTIPOVERTY POLICY Martin Ravallion Working Paper 19210 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19210 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2013 For comments the author thanks Robert Allen, Tony Atkinson, Pranab Bardhan, Francois Bourguignon, Denis Cogneau, Sam Fleischacker, Pedro Gete, Karla Hoff, Ravi Kanbur, Charles Kenny, Sylvie Lambert, Peter Lindert, Will Martin, Alice Mesnard, Branko Milanovic, Johan Mistiaen, Thomas Pogge, Gilles Postel-Vinay, John Rust, Agnar Sandmo, Amartya Sen, Dominique van de Walle and participants at presentations at the World Bank, the Midwest International Economic Development Conference at the University of Wisconsin Madison, the Paris School of Economics, the Canadian Economics Association and the 12th Nordic Conference on Development Economics. The paper’s title owes a debt to Gertrude Himmelfarb’s (1984), The Idea of Poverty: England in the Early Industrial Age. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Martin Ravallion. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Idea of Antipoverty Policy Martin Ravallion NBER Working Paper No. 19210 July 2013 JEL No. B1,B2,I38 ABSTRACT How did we come to think that eliminating poverty is a legitimate goal for public policy? What types of policies have emerged in the hope of attaining that goal? The last 200 years have witnessed a dramatic change in thinking about poverty. -

New Dynamics for Europe: Reaping the Benefits of Socio-Ecological Transition

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aiginger, Karl; Schratzenstaller, Margit Research Report New Dynamics for Europe: Reaping the Benefits of Socio-ecological Transition. Synthesis Report Part I WWWforEurope Deliverable, No. 11 Provided in Cooperation with: WWWforEurope - WelfareWealthWork, Wien Suggested Citation: Aiginger, Karl; Schratzenstaller, Margit (2016) : New Dynamics for Europe: Reaping the Benefits of Socio-ecological Transition. Synthesis Report Part I, WWWforEurope Deliverable, No. 11, WWWforEurope, Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/169308 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Christopher D. Carroll

December 21, 2012 Christopher D. Carroll Professor of Economics 410{516{7602 (o) Department of Economics 410{516{7600 (f) Johns Hopkins University [email protected] Baltimore, MD 21218-2685 http://econ.jhu.edu/people/carroll Education BA in Economics, magna cum laude, Harvard College, 1986. Honors: Early selection to Phi Beta Kappa, 1985. John Harvard Scholarship 1982-1986. Presidential Scholar, 1982. PhD in Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990. Honors: National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship Fields: Macroeconomics, Public Finance Current Appointments 2001-present Professor of Economics, Johns Hopkins University 2001-2011 National Bureau of Economic Research, Research Associate 2011-2016 National Bureau of Economic Research, Governing Board Member 2000-present Member, Conference on Research in Income and Wealth 2006-present Member, Center for Financial Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt Previous Appointments and Visiting Positions 2010-Fall Visiting Professor, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance, Rome (2010-12 to 2011-01) 2010-Fall Visiting Professor, University College, London (2010-10 to 2010-11) 2009-2010 Senior Economist, President's Council of Economic Advisers 2002-Fall Visiting Professor, European University Institute, Florence 1999-Fall Visiting Fellow, Center on Social and Economic Dynamics, Brookings Institution 1997-1998 Senior Economist, President's Council of Economic Advisers 1996-2001 Associate Professor of Economics, Johns Hopkins University 1995-1996 Assistant Professor of Economics, Johns Hopkins University 1995-2001 National Bureau of Economic Research, Faculty Research Fellow 1990-1995 Staff Economist, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 1989-1990 Teaching Assistant, Department of Economics, MIT 1986-1990 Research Assistant to Professor Lawrence H. Summers Professional Honors 1998 Paul A. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Michael Parkin DATE of BIRTH

CURRICULUM VITAE (October 2011) NAME: Michael Parkin DATE OF BIRTH: February 21, 1939 MARITAL STATUS: Married: Dr. Robin Bade Children: Catherine (1964), Richard (1965), Ann (1967) CITIZENSHIP: Canadian, British, Australian HOME ADDRESS: 128 Bloomfield Drive, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 1P3 Telephone: 519-657-2622 Facsimile: 519-657-4751 BUSINESS ADDRESS: Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 5C2 Telephone: 519-661-3500 Facsimile: 519-661-3666 EDUCATION: 1952-55 Barnsley Secondary Technical School 1955-60 Correspondence courses 1960-63 University of Leicester DEGREES HELD: 1960 Associate of Institute of Management Accountants AIMA 1963 B.A. (Leicester), First class honors 1970 M.A. Economics (Manchester) 2010 D. Litt. (Leicester), Honorary APPOINTMENTS: 1955-1960 Cost accountancy in steel industry 1963-1964 Assistant Lecturer, University of Sheffield 1964-1966 Lecturer, University of Leicester 1967-1969 Lecturer, University of Essex 1969-1970 Senior Lecturer, University of Essex 1970-1975 Professor, University of Manchester 1975-2004 Professor, University of Western Ontario 2004- Professor Emeritus, University of Western Ontario 1 VISITING APPOINTMENTS: 1972 Visiting Professor, Brown University 1973 Visiting Professor, University of New South Wales 1973 Visiting Senior Research Economist, Reserve Bank of Australia 1974 Visiting Professor, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India 1979-1980 Visiting Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University 1983 Visiting Scholar from Abroad, Bank of Japan, Tokyo 1991 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1992-1993 Norwich Australia Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1993 Erskine Visiting Fellow, Canterbury University, Christchurch, New Zealand 1994 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1995 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia RESEARCH GRANTS AND AWARDS: 1968-1970 The Portfolio Behaviour of the U.K.