Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion in the Fintech Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does the Hype Surrounding Fintechs Lead to an Overvaluation of Their Stock Prices ?

http://lib.ulg.ac.be http://matheo.ulg.ac.be Does the hype surrounding FinTechs lead to an overvaluation of their stock prices ? Auteur : Lebailly, Catherine Promoteur(s) : Hubner, Georges Faculté : HEC-Ecole de gestion de l'ULg Diplôme : Master en sciences économiques,orientation générale, à finalité spécialisée en Economics and Finance Année académique : 2016-2017 URI/URL : http://hdl.handle.net/2268.2/3573 Avertissement à l'attention des usagers : Tous les documents placés en accès ouvert sur le site le site MatheO sont protégés par le droit d'auteur. Conformément aux principes énoncés par la "Budapest Open Access Initiative"(BOAI, 2002), l'utilisateur du site peut lire, télécharger, copier, transmettre, imprimer, chercher ou faire un lien vers le texte intégral de ces documents, les disséquer pour les indexer, s'en servir de données pour un logiciel, ou s'en servir à toute autre fin légale (ou prévue par la réglementation relative au droit d'auteur). Toute utilisation du document à des fins commerciales est strictement interdite. Par ailleurs, l'utilisateur s'engage à respecter les droits moraux de l'auteur, principalement le droit à l'intégrité de l'oeuvre et le droit de paternité et ce dans toute utilisation que l'utilisateur entreprend. Ainsi, à titre d'exemple, lorsqu'il reproduira un document par extrait ou dans son intégralité, l'utilisateur citera de manière complète les sources telles que mentionnées ci-dessus. Toute utilisation non explicitement autorisée ci-avant (telle que par exemple, la modification du document ou son résumé) nécessite l'autorisation préalable et expresse des auteurs ou de leurs ayants droit. -

(Automated Teller Machine) and Debit Cards Is Rising. ATM Cards Have A

Consumer Decision Making Contest 2001-2002 Study Guide ATM/Debit Cards The popularity of ATM (automated teller machine) and debit cards is rising. ATM cards have a longer history than debit cards, but the National Consumers League estimates that two-thirds of American households are likely to have debit cards by the end of 2000. It is expected that debit cards will rival cash and checks as a form of payment. In the future, “smart cards” with embedded computer chips may replace ATM, debit and credit cards. Single-purpose smart cards can be used for one purpose, like making a phone call, or riding mass transit. The smart card keeps track of how much value is left on your card. Other smart cards have multiple functions - serve as an ATM card, a debit card, a credit card and an electronic cash card. While this Study Guide will not discuss smart cards, they are on the horizon. Future consumers who understand how to select and use ATM and debit cards will know how to evaluate the features and costs of smart cards. ATM and Debit Cards and How They Work Electronic banking transactions are now a part of the American landscape. ATM cards and debit cards play a major role in these transactions. While ATM cards allow us to withdraw cash to meet our needs, debit cards allow us to by-pass the use of cash in point-of-sale (POS) purchases. Debit cards can also be used to withdraw cash from ATM machines. Both types of plastic cards are tied to a basic transaction account, either a checking account or a savings account. -

Mckinsey on Payments

Volume 8, Number 21 May 2015 McKinsey on Payments Foreword 1 Gauging the disruptive potential of digital wallets 3 While they have established a solid foundation for growth, digital wallets are by no means a guaranteed success. They must continue to evolve if they are to have a truly disruptive impact on the payments landscape. Providers can improve their chances by focusing on six “markers” for success in payments innovation. New partnership models in transaction banking 11 A number of trends are leading to a fundamental rethinking of the traditional model by which banks offer transaction banking services to clients outside their established markets. Four distinct partnership models offer the best opportunities for banks seeking to succeed in an evolving landscape. Toward an Internet of Value: An interview with Chris Larsen, 19 CEO of Ripple Labs McKinsey on Payments sits down with the co-founder of Ripple Labs to discuss the nuts and bolts of the Ripple protocol, the implications for the correspondent banking model, and the emergence of an “Internet of Value.” Faster payments: Building a business, not just an infrastructure 23 A faster payments infrastructure is not an end in itself, it is an opportunity for banks to deliver innovative products and services in both consumer and corporate payments. To monetize this opportunity, financial institutions should focus relentlessly on design, customer experience, accessibility and convenience. Faster payments: Building a business, not just an infrastructure 23 Faster payments: Building a business, not just an infrastructure To date, most discussions about building a “faster payments” system have focused primarily on speed and “plumbing.” Even more important, however, are the innovative products and services that an enhanced infrastructure will allow financial institutions to bring to market. -

Financial Inclusion in Colombia: a Scoping Literature Review

Intangible Capital IC, 2017 – 13(3): 582-614 – Online ISSN: 1697-9818 – Print ISSN: 2014-3214 https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.946 Financial inclusion in Colombia: A scoping literature review Ulf Thoene , Álvaro Turriago-Hoyos* Universidad de La Sabana (Colombia) [email protected], *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received November, 2016 Accepted March, 2017 Abstract Purpose: The paper provides an extensive, comprehensive and up-to-date qualitative scoping literature review of financial inclusion and other related concepts, and focuses in particular on the Colombian context, and the accessibility as well as barriers to banking services. It structures the themes and dimensions of scholarly debates on financial inclusion in the literature highlighting avenues for future research to fill various gaps. Design/methodology: This scoping literature review rigorously identifies the most relevant research and variables pertaining to financial inclusion and social innovation. Findings: Based on a scoping literature review, a comprehensive framework of key concepts of financial inclusion, scholarly contributions, countries and variables is presented. Research limitations/implications: Owing to the methodological approach of this paper and its rather theoretical nature, this research seeks to enrich scientific debates pertaining to the empirical data displayed, especially on the case of Colombia. Practical implications: The most central variables that are linked to the theme of financial inclusion are explored, and hence this paper forms a basis for future qualitative and quantitative studies. Social implications: This research article contributes to public policy making on financial inclusion aimed at reducing levels of socio-economic inequality. -582- Intangible Capital – https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.946 Originality/value: In business and management research a degree of conceptual confusion prevails on the theme of financial inclusion. -

Is China's New Payment System the Future?

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | JUNE 2019 Is China’s new payment system the future? Aaron Klein BROOKINGS INSTITUTION ECONOMIC STUDIES AT BROOKINGS Contents About the Author ......................................................................................................................3 Statement of Independence .....................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 Understanding the Chinese System: Starting Points ............................................................ 6 Figure 1: QR Codes as means of payment in China ................................................. 7 China’s Transformation .......................................................................................................... 8 How Alipay and WeChat Pay work ..................................................................................... 9 Figure 2: QR codes being used as payment methods ............................................. 9 The parking garage metaphor ............................................................................................ 10 How to Fund a Chinese Digital Wallet .......................................................................... -

Financial Inclusion: the Indian Experience

FINANCIAL INCLUSION - INDIAN EXPERIENCE Financial Inclusion (FI) “Simplicity and reliability in financial inclusion in India, though not a cure all, can be a way of liberating the poor from dependence on indifferently delivered public services. In order to draw in the poor, the products should address their needs — a safe place to save, a reliable way to send and receive money, a quick way to borrow in times of need or to escape the clutches of the money lender, easy to understand life and health insurance and an avenue to engage in savings for the old age.” Raghuram Rajan, Governor, Reserve Bank of India Status of financial coverage in India u 246.7 million households in the country, 58.7% households had access to banking services as per Census 2011 u 54.46% rural u 67.68% urban u The banking network comprises of 128,397 branches and 189,844 ATMs u 38.2% branches and 14.58% ATMs are in rural areas u Left out of this coverage u Villages <2000 population u Migrant labourers and poor working in informal sector u Small and marginal farmers practising rain-fed agriculture u Women Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) National Mission on Financial Inclusion was announced by Shri Narendra Modi, Prime Minister, in his Independence Day Speech on August 15, 2014. Scope and Plan under PMJDY (i) Universal access to banking facilities for all households across the country through a bank branch or a fixed point Business Correspondent (BC) within a reasonable distance (60 million rural and 15 million urban are uncovered). -

List of Brands

Global Consumer 2019 List of Brands Table of Contents 1. Digital music 2 2. Video-on-Demand 4 3. Video game stores 7 4. Digital video games shops 11 5. Video game streaming services 13 6. Book stores 15 7. eBook shops 19 8. Daily newspapers 22 9. Online newspapers 26 10. Magazines & weekly newspapers 30 11. Online magazines 34 12. Smartphones 38 13. Mobile carriers 39 14. Internet providers 42 15. Cable & satellite TV provider 46 16. Refrigerators 49 17. Washing machines 51 18. TVs 53 19. Speakers 55 20. Headphones 57 21. Laptops 59 22. Tablets 61 23. Desktop PC 63 24. Smart home 65 25. Smart speaker 67 26. Wearables 68 27. Fitness and health apps 70 28. Messenger services 73 29. Social networks 75 30. eCommerce 77 31. Search Engines 81 32. Online hotels & accommodation 82 33. Online flight portals 85 34. Airlines 88 35. Online package holiday portals 91 36. Online car rental provider 94 37. Online car sharing 96 38. Online ride sharing 98 39. Grocery stores 100 40. Banks 104 41. Online payment 108 42. Mobile payment 111 43. Liability insurance 114 44. Online dating services 117 45. Online event ticket provider 119 46. Food & restaurant delivery 122 47. Grocery delivery 125 48. Car Makes 129 Statista GmbH Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 2848 41 0 Fax +49 40 2848 41 999 [email protected] www.statista.com Steuernummer: 48/760/00518 Amtsgericht Köln: HRB 87129 Geschäftsführung: Dr. Friedrich Schwandt, Tim Kröger Commerzbank AG IBAN: DE60 2004 0000 0631 5915 00 BIC: COBADEFFXXX Umsatzsteuer-ID: DE 258551386 1. -

Definitions the Reports Take Into Account a Broad Definition of B2C E-Commerce, Which Might Include Mobile Commerce

2 3 GENERAL METHODOLOGY OF MARKET REPORTS Secondary Market Research The reports are compiled based on secondary market research. Secondary research is information gathered from previously published sources. Our reports are based on information and data acquired from national and international statistical offices, industry and trade associations, business reports, business and company databases, journals, company registries, news portals and many other reliable sources. By using various sources we ensure maximum objectivity for reported data. As a result, companies gain a precise and unbiased impression of the market situation. Cross referencing of data is conducted in order to ensure validity and reliability. The source of information and its release date are provided on every chart. It is possible that the information contained in one chart is derived from several sources. If this is the case, all sources are mentioned on the chart. The reports include mainly data from the last 12 months prior to the date of report publication. Exact publication dates are mentioned in every chart. Definitions The reports take into account a broad definition of B2C E-Commerce, which might include mobile commerce. As definitions may vary among sources, exact definition used by the source (if available) is included at the bottom of the chart. Chart Types Our reports include text charts, pie charts, bar charts, rankings, line graphs and tables. Every chart contains an Action Title, which summarizes the main idea/finding of the chart and a Subtitle, which provides necessary information about the country, the topic, units or measures of currency, and the applicable time period(s) to which the data refers. -

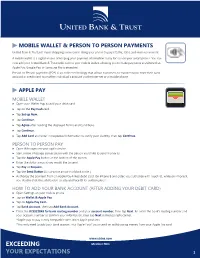

Mobile Wallet Guide

MOBILE WALLET & PERSON TO PERSON PAYMENTS United Bank & Trust just made shopping even easier! Using your phone to pay is faster, safer, and more convenient. A mobile wallet is a digital means of keeping your payment information ready for use on your smart-phone. You can now add your United Bank & Trust debit card to your mobile wallet, allowing you to make payments anywhere that Apple Pay, Google Pay, or Samsung Pay is accepted. Person-to-Person payments (P2P) is an online technology that allows customers to transfer funds from their bank account or credit card to another individual’s account via the Internet or a mobile phone. APPLE PAY MOBILE WALLET ▶ Open your Wallet App to add your debit card. ▶ Tap on the Pay Cash card. ▶ Tap Set up Now. ▶ Tap Continue. ▶ Tap Agree after reading the displayed Terms and Conditions. ▶ Tap Continue. ▶ Tap Add Card and enter in requested information to verify your identity, then tapContinue. PERSON TO PERSON PAY ▶ Open iMessages on your apple device. ▶ Start a new iMessage conversation with the person you’d like to send money to. ▶ Tap the Apple Pay button at the bottom of the screen. ▶ Enter the dollar amount you would like to send. ▶ Tap Pay or Request. ▶ Tap the Send Button (it is a white arrow in a black circle.) ▶ Authorize the payment from an Apple Pay-linked debit card. On iPhone 8 and older, you authorize with Touch ID, while on iPhone X, you double-click the side button to activate Face ID for authorization. HOW TO ADD YOUR BANK ACCOUNT (AFTER ADDING YOUR DEBIT CARD) ▶ Open Settings on your mobile phone. -

Modeling Payments Regulation and Financial Change

Modeling Payments Regulation and Financial Change Matthew W. Swinehart* INTRODUCTION The dominant narrative about changes in financial technology—or “fintech” in today’s gushing parlance—is that the financial services industry is undergoing nothing short of a revolution.1 No part of the financial sector has a better claim to that revolution narrative than payment services, which every year move more than a quadrillion—or one thousand trillion—U.S. dollars globally2 and more than 175 trillion U.S. dollars in the United States alone.3 In the last two decades, payments have moved away from cash, paper checks, and other relatively slow and expensive mechanisms to incrementally faster and cheaper digital payment services. Digital payments now account for more than 80 percent of all U.S. consumer * Matthew Swinehart is the Counsel for International Trade and Financial Regulatory Policy, and Lead Financial Services Negotiator, at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The views expressed here are the author’s own and not necessarily the views of the Department of the Treasury or the United States government. The author thanks Steven Schwarcz, Ronald Mann, Christopher Bradley, Michael Radolinski, Jeff Siegel, and the participants of the 2018 National Business Law Scholars Conference at the University of Georgia School of Law. 1. See, e.g., Nathaniel Popper, Where Finance and Technology Come Together, N.Y. TIMES (Nov. 14, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/15/business/dealbook/where-finance-and- technology-come-together.html [https://perma.cc/ZR6M-8LU5] (cataloguing fintech companies’ assessments of their own potential). Most definitions of “fintech” in use today focus on the commercialization of new technology to a degree noticeable in the market. -

Identity Theft/Fraud

MARYLAND POLICE AND CORRECTIONAL TRAINING COMMISSIONS LESSON PLAN COURSE TITLE: Police Entry-level Training Program LESSON TITLE: Identity Theft/Fraud PREPARED BY: James A. Durner DATE: 4-18-11 ADAPTED FROM: REVIEWED/UPDATED: 7 - 29 - 13 TIME FRAME PARAMETERS Suggested Length: Audience: entry-level law 4.0 Hours (entry-level) enforcement recruits; or 2.0 Hours (in-service level) in-service personnel; Number: varies Space: classroom TRAINING OBJECTIVES EVALUATION TECHNIQUE TERMINAL OBJECTIVE: [01.07] 1. Test questions; and Given various criminal situations demonstrate 2. Practical exercises/scenarios. the ability to identify elements of a given crime, utilizing the Annotated Code of Maryland and/or the Digest of Criminal Laws, that enable an officer to make a warrant-less arrest. ENABLING OBJECTIVES: Define the term IDENTITY THEFT. Identify the basic elements of the crime of IDENTITY THEFT/FRAUD as contained in the Annotated Code of Maryland. [01.07.34] TERMINAL OBJECTIVE: [04.04] Identify the resources available to an officer while conducting a criminal investigation. ENABLING OBJECTIVE: Identify the resources available to the officer for crimes involving IDENTITY THEFT/FRAUD. [04.03.21] 1 TERMINAL OBJECTIVE: [04.05] Identify resources available to a crime victim. ENABLING OBJECTIVE: [04.05.19] Identify resources available to the victim for crimes involving IDENTITY THEFT/FRAUD. TERMINAL OBJECTIVE: [04.23] Identify the basic responsibility of the officer when Investigating the crime of identity theft. TERMINAL OBJECTIVE: [07.05] Demonstrate completion of acceptable police reports for various offenses/incidents/situations. ENABLING OBJECTIVE: Apply the law as contained in the Annotated Code of Maryland Criminal Law that requires a law enforcement officer to prepare and file a report from the victim of IDENTITY THEFT/FRAUD. -

Guidance on Financial Inclusion and Financial Health Target Setting 4 Table of Contents Introduction

Guidance for banks Financial Inclusion and Financial Health Target Setting Principles for Responsible Banking Acknowledgments The content of this document is based on discussions and work undertaken in the Principles for Responsible Banking Target Setting for Financial Inclusion and Financial Health working group. We also wish to acknowledge contributions made by the following external stakeholders: International Finance Corporation, Office of United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Advo- cate for Inclusive Finance for Development (UNSGSA), European Banking Federation, Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) and UNI Global Union. Project Team Leigh Smyth Maria Eugenia Sosa Taborda Laxmi Aeshwarya Kumar Global Social Inclusion Consultant Johanna Dichtl Puleng Ndjwili-Potele Published by UNEP Finance Initiative UNEP Finance Initiative in April 2021 International Environment House 11–13 Chemin des Anémones Copyright © UNEP Finance Initiative CH-1219 Châtelaine, Geneva Switzerland Table of contents Introduction 5 Framework for financial inclusion and financial health 7 Operational process for setting targets 9 Step 1: Understand your bank’s country context and national policies Step 2: Set baselines and identify priorities Step 3: Set SMART targets Step 4: Determine measures and actions Step 5: Define Key Performance Indicators Examples of targets 15 Appendix 25 Appendix A: World Bank database to understand your country context. Appendix B: Other resources to understand your country context. Appendix C: Potential KPIs to set baselines and targets. Appendix D: Vulnerability and equality Appendix E: Examples of financial inclusion and financial health initiatives Principles for Responsible Banking. Guidance on financial inclusion and financial health target setting 4 Table of contents Introduction Financial inclusion and financial health are cornerstones for international development.