Journal of Christian Legal Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Fewer Than 11 Applicants Attorneys Admitted in Other Jurisdictions Less

GENERAL STATISTICS REPORT JULY 2018 CALIFORNIA BAR EXAMINATION OVERALL STATISTICS FOR CATEGORIES WITH MORE THAN 11 APPLICANTS WHO COMPLETED THE EXAMINATION First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Applicant Group Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass General Bar Examination 5132 2816 54.9 2939 468 15.9 8071 3284 40.7 Attorneys’ Examination 297 121 40.7 225 48 21.3 522 169 32.4 Total 5429 2937 54.1 3164 516 16.3 8593 3453 40.2 DISCIPLINED ATTORNEYS EXAMINATION STATISTICS Took Pass %Pass CA Disciplined Attorneys 19 1 5.3 GENERAL BAR EXAMINATION STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Law School Type Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass CA ABA Approved 3099 1978 63.8 1049 235 22.4 4148 2213 53.4 Out-of-State ABA 924 538 58.2 417 52 12.5 1341 590 44.0 CA Accredited 233 38 16.3 544 51 9.4 777 89 11.5 CA Unaccredited 66 10 15.2 259 22 8.5 325 32 9.8 Law Office/Judges’ Chambers * * * Foreign Educated/JD Equivalent 149 28 18.8 171 24 14.0 320 52 16.3 + One Year US Education US Attorneys Taking the 295 172 58.3 130 44 33.8 425 216 50.8 General Bar Exam1 Foreign Attorneys Taking the 352 46 13.1 309 38 12.3 661 84 12.7 General Bar Exam2 3 4-Year Qualification * 30 0 0.0 36 1 2.8 Schools No Longer in Operation * 26 1 3.8 32 4 12.5 * Fewer than 11 Applicants 1 Attorneys admitted in other jurisdictions less than four years must take and those admitted four or more years may elect to take the General Bar Examination. -

Inside: Five Clinics Deepen Experiential Learning Opportunities

DUKE MAGAZINE LAW Spring 2003 | Volume 21 Number 1 Spring 2003 Volume 21 Number 1 Volume Inside: Five Clinics Deepen Experiential Learning Opportunities at Duke Law School Also: Walter Dellinger, Ken Starr: Supreme Court Advocates in High Demand From the Dean his issue of Duke Law Magazine organizations in low-wealth areas highlights a number of exciting that need legal and business planning developments at the Law School services in order to advance projects Tgiving students opportunities to designed to improve the economic base develop their legal skills and judgment of the community. Students in the in real cases involving real people Children’s Education Law Clinic in real time. become advocates for children seeking The stepped-up emphasis on experi- appropriate educational services in area ential learning is not at the expense of schools. Students in the Duke Law the analytical training that takes place Clinic for the Special Court in Sierra in the classroom. Learning to think Leone provide research and counseling and reason “like a lawyer” remains the services to officials in Sierra Leone who central focus of the educational mis- are establishing a unique form of war sion of Duke Law School. Hands-on crimes tribunal. learning extends what students learn in Along with our legal clinics remain the classroom, helping them to opera- a robust set of clinical offerings that tionalize their analytical training and give students opportunities in simulat- often motivating them to take more ed settings to practice their legal skills. seriously their entire educational pro- Trial Practice remains an extremely of our graduates and a number of gram. -

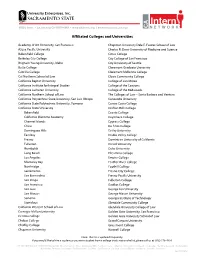

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

Institution Name Department Alliant International University California

Institution Name Department Alliant International University California School of Professional Psychology Azusa Pacific University Graduate & Professional Admissions Azusa Pacific University Leung School of Accounting Azusa Pacific University Psychology Blueprint Test Preparation Brunel University London International Programmes California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Graduate Business Programs California State Univeristy, Dominguez Hills CBAPP - MBA/MPA Rongxiang Xu College of Health and Human California State University, Los Angeles Services Dean's Office College of Engineering, Computer Science, and California State University, Los Angeles Technology California State University, Los Angeles College of Natural and Social Sciences Dean's Office Charter College of Education Office for Student California State University, Los Angeles Services California State University, Los Angeles College of Professional and Global Education California State University, Los Angeles College of Arts and Letters California State University, Los Angeles College of Business and Economics California Baptist University Graduate Admissions California Institute of Advanced Management (CIAM) Marketing California State University Long Beach College of Education California State University Northridge Accounting & Information Systems California State University San Bernardino MBA Program California State University San Bernardino Graduate Studies California State University San Marcos Office of Graduate Studies & Research California State University, Fullerton -

Trinity JD Scholarships

SCHOLARSHIPS 12 MERIT-BASED Dean’s Full-Tuition + Stipend Justice A limited number of full-tuition scholarships are offered by Trinity This scholarship is awarded to incoming students based upon Law School to qualified students of high academic caliber and academic excellence and LSAT performance. To be considered for personal excellence who seek to serve in the practice of law. this scholarship, student’s previous academic performance will weigh heavily in combination with their LSAT score to provide financial . 100% Tuition Scholarship ($31,050 value) + assistance for students who show potential to have a high academic $500-$1500 monthly stipend performance at TLS. It is possible to have this renewed beyond the . Must have LSAT score in 60th percentile or higher first year if specific academic requirements are maintained. (155-180). Must be enrolled in 12 or more units per semester (30 units . $5,000 - $7,500 per year) and maintain a cumulative GPA of A- (3.5). Must have LSAT score above the 33rd percentile Cannot be combined with any other scholarship. (147-148). Scholarship is reviewed for GPA requirement every semester. Must be enrolled in 12 or more units per semester (30 units per year) and maintain a cumulative GPA of B (3.0). Cannot be combined with any other scholarship. Dean’s Full-Tuition . Scholarship is reviewed for GPA requirement every semester. A limited number of full-tuition scholarships are offered by Trinity Law School to qualified students of high academic caliber and personal excellence who seek to serve in the practice of law. Legal Studies . 100% Tuition Scholarship ($31,050 value) This scholarship is awarded to incoming students based upon . -

Theological Basis of Ethics

TMSJ 11/2 (Fall 2000) 139-153 THEOLOGICAL BASIS OF ETHICS Larry Pettegrew Professor of Theology Systematic theology must serve as a foundation for any set of moral standards that pleases God and fulfills human nature. Establishing such a set is difficult today because of the emergence of the postmodernism which denies the existence of absolute truth, absolute moral standards, and universal ethics. Advances in science, medicine, and technology increase the difficulty of creating a system of Christian ethics. The inevitable connection between ethics and systematic theology requires that one have a good foundation in systematic theology for his ethics. A separation between the two fields occurred largely as a result of the Enlightenment which caused theology to be viewed as a science. Since the study of a science must be separate from a religious perspective, theology underwent a process of becoming a profession and the responsibility for educating theologians became the responsibility of the college rather than the church. This solidified the barrier between theology and ethics. Who God is must be the root for standards of right and wrong. God’s glory must be the goal of ethics. Love for God must be the basis for one’s love for and behavior toward his fellow man. Other doctrines besides the doctrine of God, especially bibliology, play an important role in determining right ethical standards. * * * * * One of the most popular American movies last year was based on a book by John Irving entitled The Cider House Rules. The Cider House Rules tells the story of a young man eager to discover what life is like outside of the orphanage in which he has spent his childhood years. -

Natural Theology in Evolution: a Review of Critiques and Changes

This is the author’s preprint version of the article. The definitive version is published in the European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Vol.9. No. 2. 83-117. Natural Theology in Evolution: A Review of Critiques and Changes Dr. Erkki Vesa Rope Kojonen University of Helsinki, Faculty of Theology Abstract The purpose of this article is to provide a broad overview and analysis of the evolution of natural theology in response to influential criticiques raised against it. I identify eight main lines of critique against natural theology, and analyze how defenders of different types of natural theology differ in their responses to these critiques, leading into several very different forms of natural theology. Based on the amount and quality of discussion that exists, I argue that simply referring to the critiques of Hume, Kant, Darwin and Barth should no longer be regarded as sufficient to settle the debate over natural theology. Introduction Adam, Lord Gifford (1820-1887), who in his will sponsored the ongoing Gifford Lectures on natural theology, defined natural theology quite broadly as “The Knowledge of God, the Infinite, the All, the First and Only Cause, the One and the Sole Substance, the Sole Being, the Sole Reality, and the Sole Existence, the Knowledge of His Nature and Attributes, the Knowledge of the Relations which men and the whole universe bear to Him, the Knowledge of the Nature and Foundation of Ethics or Morals, and of all Obligations and Duties thence arising.” Furthermore, Gifford wanted his lecturers to treat this natural knowledge of God and all of these matters “as a strictly natural science, the greatest of all possible sciences, indeed, in one sense, the only science, that of Infinite Being, without reference to or reliance upon any supposed special exceptional or so- 1 called miraculous revelation. -

Feb 2018 Cal Bar Exam

GENERAL STATISTICS REPORT FEBRUARY 2018 CALIFORNIA BAR EXAMINATION1 OVERALL STATISTICS FOR CATEGORIES WITH MORE THAN 11 APPLICANTS WHO COMPLETED THE EXAMINATION First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Applicant Group Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass General Bar Examination 1267 498 39.3 3434 784 22.8 4701 1282 27.3 Attorneys’ Examination 391 211 54.0 211 50 23.7 602 261 43.4 Total 1658 709 42.8 3645 834 22.9 5303 1543 29.1 DISCIPLINED ATTORNEYS EXAMINATION STATISTICS Took Pass % Pass CA Disciplined Attorneys 25 0 0 GENERAL BAR EXAMINATION STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Law School Type Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass CA ABA Approved 316 143 45.3 1423 445 31.3 1739 588 33.8 Out-of-State ABA 164 58 35.4 538 144 26.8 702 202 28.8 CA Accredited 122 28 23.0 570 52 9.1 692 80 11.6 CA Unaccredited 75 16 21.3 244 18 7.4 319 34 10.7 Law Office/Judges’ * * * Chambers Foreign Educated/JD 68 7 10.3 157 17 10.8 225 24 10.7 Equivalent + One Year US Education US Attorneys Taking the 310 204 65.8 140 64 45.7 450 268 59.6 General Bar Exam2 Foreign Attorneys 198 38 19.2 312 44 14.1 510 82 16.1 Taking the General Bar Exam3 4-Year Qualification4 * 19 0 0 26 0 0 Schools No Longer in * 29 0 0 33 1 3.0 Operation * Fewer than 11 Applicants 1 These statistics were compiled using data available as of the date results from the examination were released. -

Full-Time and Regular Faculty 1

Full-time and Regular Faculty 1 participated as a member of the Megan’s Law Task Force, the U.S.- FULL-TIME AND REGULAR Medico Border Task Force, and the National Association of Attorneys General Task Force concerning the Victim’s Rights Amendment to the FACULTY U.S. Constitution. He is a recipient of an Outstanding Achievement Award from Victims, Families, and Survivors of the Oklahoma City Bombing, Adeline Allen the Randolph Award, the highest award given by the United States Department of Justice, and the Marvin Award, given each year to the Associate Professor Adeline Allen received her B.S. in Physical outstanding attorney by the National Association of Attorneys General. Anthropology from UCLA, cum laude, and her J.D. from Regent University Professor Holsclaw also served as Legislative Counsel to Congressman School of Law in the honors track. She served as the Executive Editor Dan Lungren from 2005-2013 and served as Interim Dean of Trinity Law of the Regent University Law Review. Professor Allen was a Visiting School in 2001. Professor Holsclaw teaches Criminal Law, Criminal Fellow with Princeton University’s James Madison Program in American Procedure, and Immigration Law. Ideals and Institutions for the 2017-2018 academic year. Professor Allen teaches Contracts and Torts. Daniele Le Daniele Le is an Assistant Dean at Trinity Law School, where she Narcis Brasov oversees the online Juris Doctor courses and the Legal Research & Assistant Professor Narcis Brasov received his B.A. in Philosophy and Writing program. She teaches Legal Research and Writing 1 and Legal his B.A. in Spanish from USC, his M.A. -

2016-2017 Academic Catalog

2016-2017 Academic Catalog SOUTHERN SEMINARY Table of Contents About Southern .................................................................................................................. 8 Abstract of Principles ..............................................................................................................................................................8 The Baptist Faith and Message ...........................................................................................................................................9 Mission ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Accreditation ............................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Denominational Affiliation .................................................................................................................................................. 15 Historical Sketch ..................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Academic Programs .............................................................................................................................................................. 16 Admissions ...................................................................................................................... -

Adjunct Faculty 1

Adjunct Faculty 1 Alexa Clark ADJUNCT FACULTY B.A., Scripps College M.A., Claremont McKenna College Adjunct faculty members have an ongoing involvement with the Law J.D., Gould School of Law, University of Southern California School, usually teaching at least one course each year. Certain adjunct Torts faculty members teach more courses each year. The degree to which these faculty members are able to participate in the academic and Eddie Colanter community life at the law school varies. The following faculty members B.A., University of California, San Diego are recent or present adjuncts. M.A., Simon Greenleaf College M.A., Trinity Graduate School George Ackerman Philosophy and Theology of Justice; Bioethics B.A., Florida Atlantic University M.S., Nova Southeastern University Zachary Cormier M.B.A, Nova Southeastern University B.B.A., University of New Mexico J.D., Shepard Broad College of Law, Nova Southeastern University J.D., Pepperdine University School of Law Ph.D., Capella University Constitutional Law Criminal Justice Michael Dauber Craig Alexander B.A., California State University, Sacramento A.A., West Valley Community College M.Div., Talbot Theological Seminary B.A., Santa Clara University Th.M., Talbot Theological Seminary J.D., Santa Clara Law, Santa Clara University J.D., Loyola Law School, Los Angeles Freedom of Information Act Criminal Procedure; Criminal Law; Evidence Mark Allen III William Evans B.A., Grinnell College B.A., Pennsylvania State University J.D., Loyola Law School, Los Angeles J.D., Caruso School of Law, Pepperdine University Administrative Law Contracts Matthew Batezel Anne Bachle Fifer B.A., California State University Fullerton B.A., St. -

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM to 12:10 PM 8:15 AM - 8:45 AM Morning Prayer Omni - Texas Ballroom EF Join Us for a Simple Worship Service of Scripture and Prayer

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM TO 12:10 PM 8:15 AM - 8:45 AM Morning Prayer Omni - Texas Ballroom EF Join us for a simple worship service of scripture and prayer P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Christianity and Culture Theology and Apologetics in a Pluralistic World Omni - Stockyard 1 Moderator: John Adair (Dallas Theological Seminary) 9:00 AM – 9:40 AM Daniel T. (Danny) Slavich (Cross United Church) A Credible Witness: A Pluriform Church in a Pluralist Culture 9:50 AM – 10:30 AM SuYeon Yoon (Boston University, Center for Global Christianity and Mission) Effects of Culture on Neo-Charismatic Christianity in S. Korea and N. America from 1980s-Present 10:40 AM – 11:20 AM Jeffrey M. Robinson (Grace Fellowship: A Church for All Nations) Persuasive Apologetics: Truth and Tone 11:30 AM – 12:10 PM Daniel K. Eng (Western Seminary) East Asian and Asian American Reflections on the Epistle of James P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Hermeneutics The Canon and Biblical Interpretation Omni - Fort Worth Ballroom 4 Moderator: Scott Duvall (Ouachita Baptist University) 9:00 AM – 9:30 AM Stephen Dempster (Crandall University) Canon and Context: The Hermeneutical Significance of Canonical Sequence 16 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM TO 12:10 PM 9:35 AM – 10:05 AM Darian Lockett (Talbot School of Theology) Interpreting the New Testament as Canon: Whose Intention and What Context? 10:10 AM – 10:25 AM Respondent: Matthew S. Harmon (Grace College & Theological Seminary) 10:25 AM – 10:40 AM Respondent: Patrick Schreiner (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) 10:40 AM – 10:55 AM Respondent: Matthew Barrett (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) 11:00 AM – 12:10 PM Panel Discussion P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Method in Systematic Theology Methodologies Comparative and Doctrinal Omni - Fort Worth Ballroom 5 Moderator: John C.